There’s plenty of handwringing these days over the corrosive effects of political polarization. And yes, things are pretty bad today. That said, perhaps we should take solace in the fact that things aren’t as bad right now as they were in 1866, one year after the Civil War.

To say President Andrew Johnson’s September 7, 1866, stop in Bloomington was a disaster, politically speaking, is putting it mildly. After all, it’s not every day a sitting U.S. president gets chased out of town by an unruly mob.

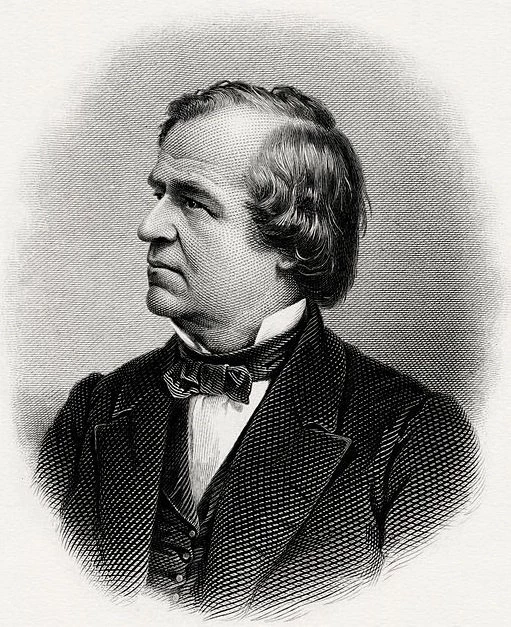

A Democrat from Tennessee, Johnson was the only southern U.S. senator to remain in the Union during the Civil War. For the 1864 presidential election, Republicans, in a conciliatory gesture to both northern and border state Democrats, picked Johnson as Abraham Lincoln’s running mate.

The following spring, Lincoln’s assassination on Good Friday vaulted Johnson into the White House, and it was only a matter of time before the stubborn, ill-tempered Tennessean clashed with Radical Republicans in Congress. At issue was the post-Civil War “reconstruction” of the secessionist South.

Many so-called “radical” Republicans favored punishing Confederate leaders and extending civil and political rights to some 4 million formerly enslaved African Americans. Johnson, on the other hand, supported the rapid reincorporation of the former Confederate states into the Union, with little or no regard to the rights of freedpeople. “This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am president, it shall be a government for white men,” Johnson told the governor of Missouri.

On August 27, 1866, President Johnson embarked on an unprecedented 18-day speaking tour in an attempt to rally northern Democrats to his cause of limited Reconstruction. The tour, which became known as the “Swing Around the Circle,” took the president and his party on a circuitous route from Washington, D.C. to New York, Chicago, St. Louis, Indianapolis, Pittsburgh—and many cities and towns in between—before heading back to the nation’s capital. The large party accompanying Johnson included Secretary of State William H. Seward, Navy Secretary Gideon Welles and Postmaster General Alexander W. Randall, as well as potential rival Ulysses S. Grant.

The “Swing” began well enough, but by the September 3 stop in Cleveland, rancorous crowds began jeering the president, saving their enthusiasm for Gen. Grant, the war hero many Republicans embraced as the true heir to the martyred Lincoln. After Chicago, the increasingly embattled Johnson and his party traveled south to St. Louis on the Chicago & Alton Railroad, with brief stops in Bloomington and elsewhere along the line.

For its part, The Pantagraph, a devoted supporter of Lincoln and now Grant, made no effort to hide its disdain for the current president, referring to Johnson as “His Accidency” or “The Presidential Demagogue.”

Anticipating the president’s passage through Bloomington, the newspaper caustically noted that the pro-Johnson crowd would consist of area residents representing “every deserter from the rebel army, every paroled rebel, every draft skulker, every draft resister, every man who opposed the war—in short, the whole [Democratic] party on hand to carry out the program of the leaders.”

On September 7, a Bloomington crowd of some 4,000 mostly Republican supporters gathered to watch the President Johnson’s train pull into the west side C&A depot. Grant appeared at the rear platform to shake hands with supporters, generating, according to The Pantagraph, “the wildest excitement we have ever witnessed.” After Grant stepped back inside the train, outnumbered Democrats countered with calls for the president.

Johnson then stepped out and attempted a speech but found it impossible to continue in the face of “deafening cries” for Grant. “If you would only be quiet you might employ this valuable time in hearing a speech,” Postmaster General Randall scolded the unruly crowd before backing down himself amid a chorus of “hisses and groans.”

Someone then called for three cheers for Grant, and the ensuing celebration was such that a number in the crowd were injured. Johnson reappeared, managed a few lines between “huzzahs” for Grant, and as he waited for the crowd to quiet down the train unceremoniously pulled out of the depot.

As a final indignity, the president’s train passed an effigy strung from a telegraph pole, the figure holding “a loaf of bread in one hand, and a lump of butter in the other” (political appointees and supporters of Johnson’s were said to comprise the “Bread and Butter Brigade.”)

The Pantagraph applauded the “spontaneous outburst of Illinois indignation” aimed at Johnson and his policies “The Copperheads,” declared the newspaper, employing the derisive term for Northern traitors during the Civil War, “know that our people have become thoroughly disgusted with the president’s insolent insults, and that the time has come for him to be met by a stern rebuke.”

Democrats made much hay over the claim that Republicans—by shouting down the president—could not countenance free speech. The Pantagraph would have none of this line of reasoning. Johnson, it argued, “has made the same speech almost every time he has spoken since he left Washington, and that has been read and reread until it has been almost committed to memory.”

In fact, the robust give-and-take between the speakers and crowd represented anything but the repression of First Amendment rights. “If there wasn’t a little the freest speech exhibited at the depot ever heard in this town, we will give up the point,” it was said. “Every man had his say, whether he was Democrat or Unionist.”

Point in fact, such a free-spirited display regarding the most contentious issue of the day would have been unthinkable in the unreconstructed South.

“When the crowd refused to hear the President the other day at the depot, it was done in a playful manner, and no one’s person was in the least danger,” reflected The Pantagraph. “Freedom of speech, however, does not exist in the South, and no one will be found hardy enough to gainsay this statement.”

The newspaper went on to note the impossibility of African-American leader Frederick Douglass—to cite one example—conducting a speaking tour in the former Confederacy to promote African-American equality.

In the end, the “Swing around the Circle” was an abject failure, as the 1866 midterm congressional elections ended in a landslide for Republicans, the party increasing its already formidable majority in Congress.

Even so, President Andrew Johnson and the Radical Republicans remained at odds, with the intractable stalemate coming to a head in 1868 when the U.S. House of Representatives impeached him, though the Senate voted for acquittal by the narrowest of margins—a single vote.