On April 10, 1860, five-and-a-half weeks before accepting the Republican nomination for president, Abraham Lincoln was in Bloomington to deliver an address on the burning issue of the day—slavery and its expansion westward.

This would prove to be Lincoln’s last major speech in a city where he spent so much time, both in the courtroom as a lawyer and on the speaker’s platform as leader of the newly formed Republican Party.

The speech is also of interest because it was the only significant one by Lincoln during a crucial stretch in his political career. Over a two-month period, from the second week of March, when he wrapped up two weeks of stumping through New England (this after his historic address at New York City’s Cooper Union), all the way through his May 18 nomination in Chicago, Lincoln made only one major address—and that was in Bloomington!

Exhausted from his early spring 1860 New England tour, Lincoln returned to Springfield and concentrated on his law practice, all the while turning down most speaking invitations. One exception, though, was a request from his Republican friends and colleagues in Bloomington.

Lincoln used his April 10 speech in Bloomington (he was in town for the spring session of the McLean County Circuit Court) to address popular sovereignty and how that principle—cherished by Democrats and despised by Republicans—related to both slavery and, strangely enough, Mormon polygamy.

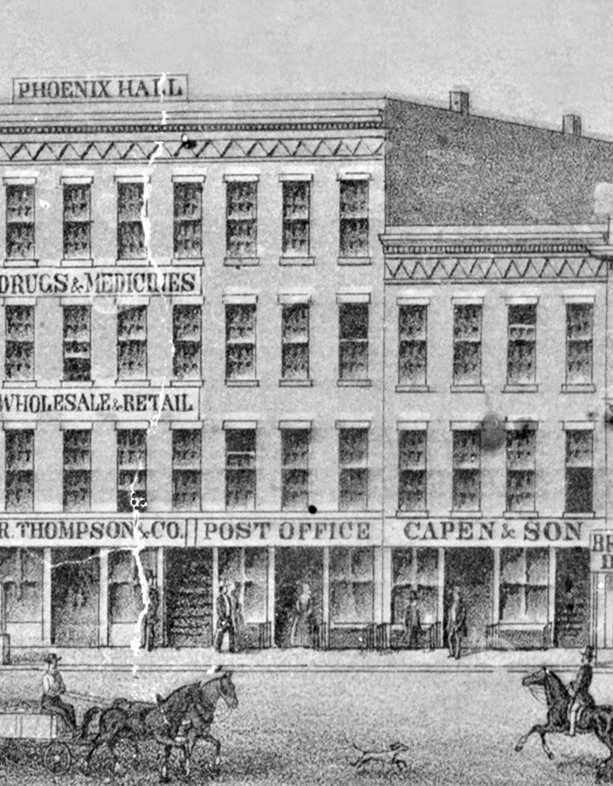

Lincoln delivered the speech at Phoenix Hall, which was located on the south side of the courthouse square. Opened in October 1858, the assembly room measured a cozy 43x105 feet, spanning as it did the upper floors of two of the five buildings that comprised the Phoenix block. (In 1917, Livingston’s department store razed five of these Greek Revival-style buildings—including the two housing Phoenix Hall—to make way for a modern department store. Today, Michael’s Restaurant occupies the street-level floor of that building.)

The only detailed record of Lincoln’s April 10, 1860 speech appeared in the April 13 edition of the Illinois Statesman, a Bloomington newspaper affiliated with the Democratic Party. The Statesman was a lively competitor to The Pantagraph, itself aligned with Lincoln and the Republican cause of halting the expansion of slavery in the western territories.

In spite of the vitriolic partisanship commonplace in the antebellum press, the Statesman’s account of Lincoln’s April 10 speech was—all things considered—both fair and (shall we say) balanced. Its version of the speech was then reprinted in the April 17 Illinois State Register, Springfield’s influential Democratic paper.

According to the Bloomington Statesman, Lincoln pointed to the supposed hypocrisy of the Democrats wishing to exercise federal power in the territories over one issue (Mormon polygamy) while steadfastly embracing a hand’s off approach over another (slavery.) Since passage of the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, Democrats, led by Sen. Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, had championed “popular sovereignty,” the idea that settlers—and not the federal government—had the right to either allow or disallow slavery in newly organized territories.

Douglas embraced popular sovereignty as the American beau ideal of self-government in action. Lincoln, in sharp contrast, found the doctrine odious because it placed both supposed political freedom and slavery on the equal moral footing. In a speech in Bloomington back in Sept. 1854, Lincoln declared that if popular sovereignty expanded slavery’s reach, it was decidedly not an expression of “self-government,” but rather one of “despotism.”

Six years later, again in Bloomington, Lincoln argued that when it came to polygamy, many Democrats ignored their beloved principle of popular sovereignty in a mad dash to squash the practice of plural marriage. For instance, just days before Lincoln’s speech, the U.S. House—with support of many Democrats—passed a bill criminalizing polygamy.

Lincoln further argued that even a milder anti-Mormon measure put forward by Congressman John A. McClernand, another Illinois Democrat, tossed aside any real concern for popular sovereignty. He noted that McClernand “proposed to suppress the evil of polygamy” by splintering the Utah Territory and having adjacent (and thus non-Mormon majority) territories absorb its constituent parts.

The Statesman, though editorially at variance with Lincoln’s views, nonetheless noted his bemusement over the Democratic Party’s dilemma. McClernand, a devotee to Douglas and popular sovereignty, could not support direct congressional action to end polygamy, so he instead crafted the backdoor political maneuver of territorial dissolution to accomplish the same.

“This inconsistency, Mr. Lincoln illustrated by a classic example of a similar inconsistency,” the Statesman noted. “‘If I cannot rightfully murder a man, I may tie him to the tail of a kicking horse, and let him kick the man to death!’”

Lincoln believed he had the Democrats cornered. “Why is not an act of dividing the Territory as much against popular sovereignty as one for prohibiting polygamy?” he asked. “If you can put down polygamy in that way, why may you not thus put down slavery?”

For its part, The Pantagraph admitted to not having “the time to write, or the space to insert, a synopsis of the speech.” The city’s Republican paper, though, did remark on size of the crowd. “Notwithstanding the rain and the mud, last night” it reported, “Phoenix Hall was full to its capacity of attentive listeners to the speech of Mr. Lincoln.”