During the summer of 1855, cholera swept through Bloomington and outlying communities. It was one of the largest outbreaks of this dreaded infectious disease in local history.

That summer 164 years ago, deaths from cholera in Bloomington totaled more than 30. Given that the city’s population was around 5,000 at the time (Normal was not established until a few years later), the number of dead in 1855 would be the equivalent—proportionally speaking—to the loss of some 1,100 Twin City residents today, given the dramatic increase in population over the ensuing years.

Cholera is most often transmitted through water or food contaminated with human waste. Back in 1855, though, the best medical minds believed the “Asiatic terror” (as cholera was sometimes called) emanated from “miasmas,” a fancy word for the fetid, odiferous vapors of garbage, sewage and other types of rotting organic material.

“Summer is at hand,” warned The Pantagraph in the latter half of May 1855. “The very hot days will soon be upon us—and so may the cholera, or some other disease—now therefore is the time to clear up the alleys, the stable litter and everything that may offend either the sight or the smell. Let us have a general slicking up.

Symptoms of cholera include watery diarrhea, cramps, dehydration, the collapse of the circulatory system and shock. What makes the disease so scary is the rapidity in which it can kill. It’s not unheard for unsuspecting carriers of the cholera bacterium to feel fine and dandy in the morning only to turn up dead by the afternoon.

Recalling the 1855 outbreak years later, Dr. Charles R. Parke said it began in the final days of July with the deaths of five or six Germans staying at a boarding house and saloon at the corner of Center and Front streets in downtown Bloomington. “We have heard of five deaths in the city and two in the country, occurring suddenly, and said to have been from cholera, within the last two or three days,” reported the Aug. 1 Pantagraph.

That was a harbinger of more death to come.

Due to the “many false and unwarrantable reports … respecting the health of our city,” Bloomington Mayor Franklin Price issued a public statement on the outbreak in the Aug. 8, 1855 Pantagraph. Included were two lists which together provided the names or identities of 23 known cholera victims who died within the city limits during the preceding two weeks.

Bloomington got off relatively easy, though, compared to the DeWitt County community of Waynesville, which lost 50 or so residents (out of a population of 300 to 350.)

At the Ackerson place outside of Waynesville, six family members were felled by the disease— John Ackerman, Sr. and his wife; their children Sarah Ann, Jane and an unnamed infant; and John’s sister, Charlotte Montgomery. Neighbors then burned down the Ackerson house and its contents, hoping the flames would rid the place of that which killed them.

On a happier note, two Ackerson children, John, Jr. and Susan, were spared, and both lived long lives and raised good-size families.

In 1934, Samantha Richards recounted her experience as a six-year-old living in Waynesville that awful summer (though she misremembered the year as 1854.) There was the time, for example, when Richards and her sister were sent on an evening errand and found a woman lying dead in the street.

The Pantagraph relayed how Richards and her mother “would sit at the window and watch neighbors carry the dead to the Evergreen Cemetery [on the village’s eastern end] … six to ten a night.”

Although Richards’ telling might contain some unwitting exaggeration, she nonetheless spoke to the raw fear and societal strain manifest in cholera outbreaks.

Community leaders often suppressed news relating to the appearance or severity of the disease for fear of depressing trade and commerce or negatively impacting hoped-for population growth. During a suspected outbreak in the spring of 1854, The Pantagraph made it clear it would not be party to such cover-ups. “We are not unaware that it is the custom with many editors to conceal the truth in such diseases, for fear that it might injure the character or the business of their place,” the newspaper declared, “but in such rascality we will not participate. Such concealment would be indictable in a court of moral equity.”

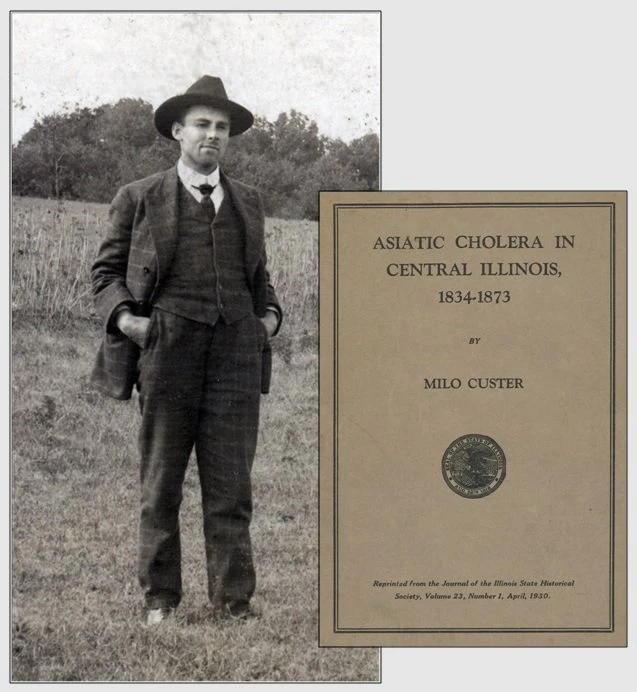

In 1930, local historian and genealogist Milo Custer, the first curator of the McLean County Historical Society (now the Museum of History), authored a research paper on 19th century area cholera mortality (see accompanying image.)

From 1834 to 1873, Custer identified at least 140 cholera deaths—clustered in 7 distinct outbreaks—in this part of Central Illinois (though the actual number was undoubtedly higher, though how much higher will remain one of those mysteries forever lost to time.)

The 1855 outbreak—which lasted from late July through the first three weeks of August—felled more than 70 residents in McLean County and the surrounding counties. Custer recorded deaths in Clarksville, Twin Grove and other rural settlements in McLean County, as well as in or near Congerville, Waynesville and elsewhere outside of McLean County.

Due to the lack of vital records (Illinois counties were not required by the state to maintain a death register until 1916), Custer relied on things like newspaper obituaries and cemetery records.

Gravestones themselves could also prove helpful. In 1941, William Brigham, superintendant of McLean County schools, said that some of the older cemeteries in the area featured headstones reading, in part, “Died of cholera.” The Lytleville Cemetery north of Heyworth was said to be one such burial ground.

In the summer of 1855, Waynesville residents struggled to make sense of the Old Testament-like plague inflicted upon their little village. “A cemetery was started north of the present community high school site, but no stones were put up and all traces of that burial grounds were lost,” remembered Samantha Richards. “Some of the farmers between Waynesville and McLean buried their dead along the rail fences.”

“But the disease died out and the dread experience was ended,” concluded The Pantagraph in its 1934 article on Richards and her firsthand account of the 1855 outbreak. “Only occasionally now does one hear a reminder of the sad experience. And it is always with the same feeling expressed by Mrs. Richards—thanks that science has made such progress that it is now unthinkable that any community should have such an experience as those pioneers of Waynesville.”

That may be true in the United States and many other nations, but cholera—although it’s treatable with rehydration, intravenous fluids and antibiotics—still plagues much of the developing world. According to the United Nations, there are an estimated 1.3 to 4 million infections and 21,000 to 143,000 cholera deaths annually.