The start of 1946-1947 school year, coming as it did a full year after the end of World War II, was a sign of the nation’s halting return to normalcy.

Yet the enormity of the global conflagration meant that prewar routine, however defined, wasn’t coming back anytime soon. For instance, in the fall of 1946, with the two local universities bursting at the seams with returning military veterans, prefabricated barracks used to house prisoners of war were brought in to serve as temporary housing.

On the other hand, enrollments were relatively steady when it came to area elementary, middle and high schools. There were 2,944 grade school and junior high students in Bloomington’s public school system, and 1,084 in the high school, for a district-wide enrollment of 4,028, a figure relatively unchanged from the previous school year’s total of 3,989.

At this time, Bloomington Public Schools included Bloomington High and ten neighborhood schools—Bent, Edwards, Emerson, Franklin, Irving, Jefferson, Lincoln, Raymond, Sheridan and Washington. Although the city was much more compact, area-wise, in 1946 than it is today, the large number of schools meant elementary age children could walk to school no mater where they lived in the city.

The war’s impact though, was felt elsewhere. There remained a scarcity of consumer goods, to cite one representative example of the many lingering effects of the ration economy. Children’s clothes were still hard to find, especially those modestly priced. The Pantagraph reported that in the weeks leading up to the start of school, mothers throughout the area were busy sewing clothes for their children.

One such mother was Eva Okell, who lived with her husband Robert and their family on Harwood Place in Bloomington. She sewed all her second-grade daughter Barbara’s school attire except for coats and leggings. She made skirts from both a pair of men’s wool trousers and “her own outmoded clothes,” saving upwards of $3 on “every homemade garment.”

In 1946, there were still plenty of rural, one-room schools out in the McLean County countryside, though their days were numbered, thanks in large part to the graveling of many township roads and the increased reliability and safety of school buses.

There were 24 fewer rural schools in the county to start the 1946 school year than the year before, with 10 of those closing due to consolidations in the Stanford area and West Township. Others shuttered due to declining enrollments. That left 158 rural schools in the county in the fall of 1946, down from 182 the year before.

The great wave of school consolidation would come two years later, in 1948, leading to the abrupt closure of the majority of McLean County’s rural schools. The county’s last remaining one-room schools, both located in Dale Township, closed after the 1959-1960 school year.

This being the Twin Cities, back to school also means back to college, and 1946 was no different.

Returning veterans flocked to the two local universities, due in great measure to the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, known popularly as the G.I. Bill. This led to acute shortages in on- and off-campus housing.

For its part, Illinois Wesleyan University placed an advertisement in The Pantagraph desperately seeking rented rooms with the hope of relieving the housing shortage facing the “largest student body” in school history.

By late August, IWU had capped enrollment at 950 students. Of those, around 480, or slightly more than half, were veterans under the G.I. Bill. The freshmen class alone included more than 180 servicemen and at least 4 servicewomen.

Relief came in the form of the aforementioned prefabricated army barracks, which in IWU’s case were shipped from a former prisoner-of-war camp in Weingarten, Mo. There was irony in housing university enrolled veterans in POW barracks, but what exactly was ironic about it no one quite knew!

The housing units included four main barracks, 100 feet long and 20 feet wide, which were then divided up into rooms. Even so, additional trailers had to be moved on or close to campus to house more students. The university also acquired two North Main Street residences and repurposed them as dormitories, renaming the old homes DeMotte Lodge and Munsell Hall.

There was an even tighter squeeze at Illinois State Normal University, despite the conservative admission policies advocated by President R.W. Fairchild. In the fall of 1946, enrollment topped 1,800, with 635 of those veterans.

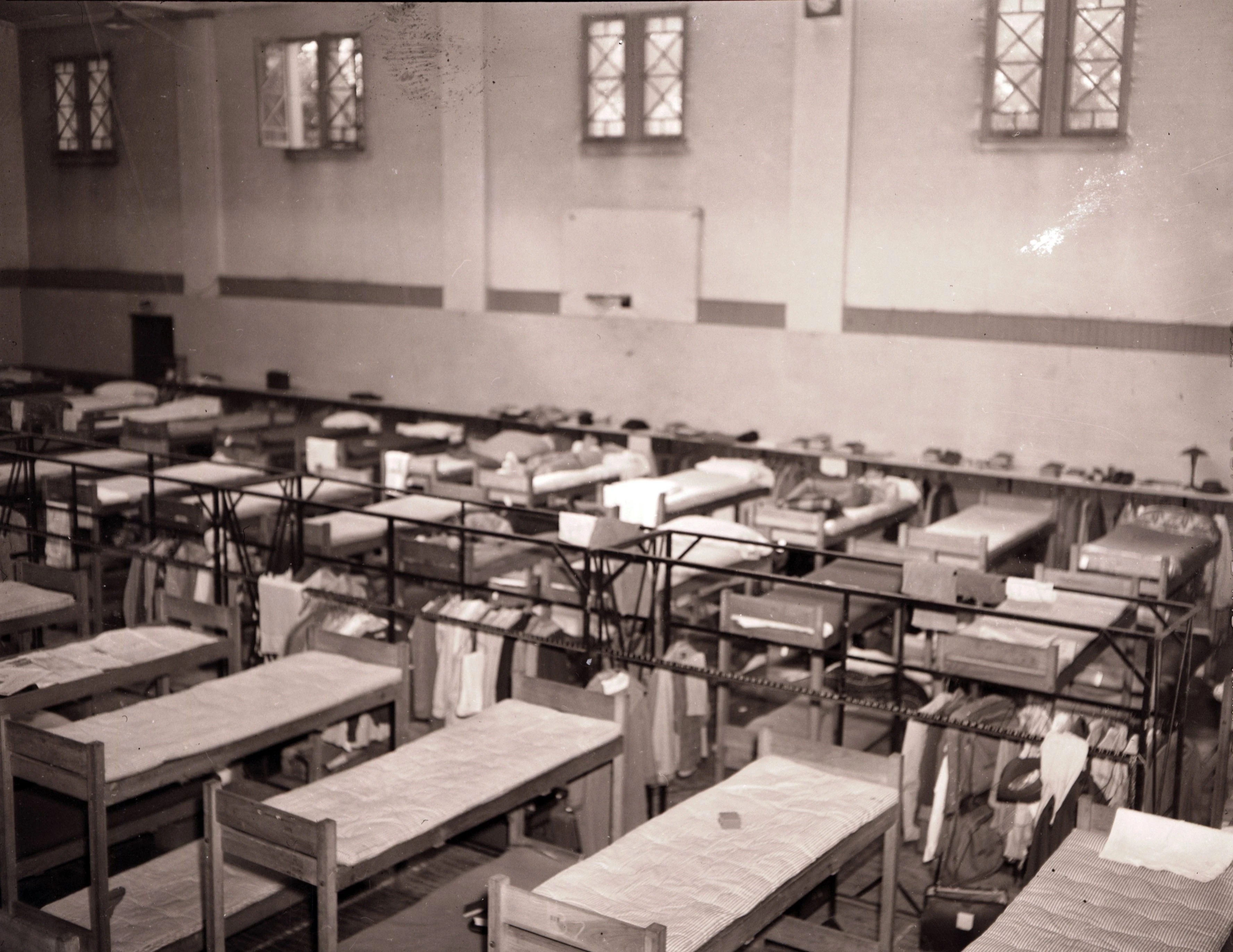

When school opened the second week of September, Fairchild had to tell some 100 veterans that they could not bring their families to campus as previously planned because the POW barracks erected on the University Farm wouldn’t be ready until October, at the earliest. Anywhere from 50 to 90 men were then temporarily housed in the Cook Hall gymnasium (see accompanying photograph), where they slept on wooden double bunks.

ISNU’s POW barracks were located at the south end of the University Farm off Sudduth Road (now College Avenue), and were open to married and single students. By the spring of 1947 there were nearly 250 men, women and children making a home in what would soon take the name Cardinal Court (the university would open a new and permanent Cardinal Court along Gregory Street in 1959; the old WW II barracks were razed in 1962).

Clearly, as evident by the growing number and size of families at Cardinal Court, veterans were busy with more than schoolwork. All this baby-making, of course, led to the baby boom generation and a sustained enrollment surge that got underway two decades later. ISNU’s first baby boom class enrolled as freshmen in the fall of 1964.

On the elementary school level, in late August 1946, teacher Lucille Murphy was preparing for her 25th year in the classroom. A Normal resident, she taught at Little Brick School, which was on West Washington Street well outside Bloomington city limits. From 1927 to 1941, Little Brick was one of several area one-room schools that served as real-world laboratories for ISNU faculty and students.

Murphy began her teaching career at Ireland Grove School, and put in 15 years at Little Red School (not to be confused with Little Brick!), located on Linden Street in north Normal.

Murray didn’t drive an automobile, so she always walked to and from school, which meant hoofing it upwards of five miles a day, depending on where she was teaching. In 1946, she lived on the 300 block of Virginia Avenue, and so rode the city bus to Euclid and Grove streets on Bloomington’s western edge, and then walked the rest of the way to Little Red School. For the 1946-1947 school year, she taught a combined first-through-fourth grade class of 20 boys and girls.