Illinois became the nation’s 21st state in 1818, meaning next year will be the Prairie State’s bicentennial. Remarkably, in nearly 200 years of statehood there has been but one total solar eclipse visible from the Land of Lincoln—though, of course, that number will increase twofold come Monday!

The first such eclipse over the State of Illinois occurred on Aug. 7, 1869, a full 148 years ago. And unlike this Monday, when a partial eclipse will be visible above The Pantagraph readership area, in 1869, Bloomington and a large swath of the state were treated to one of the grandest exhibitions the heavens have to offer—a total solar eclipse.

“Festoons of glowing wreaths hung around and within the margin, which resembled in no slight degree shreds of red-hot glass, mellowed by distance,” was how Edward R. Roe, watching from downtown Bloomington, described the moment when the moon completely obscured the sun to reveal the sun’s corona. “But with all this rippling glimmer there was no suggestion of heat. It was cold, brilliant and grand.”

A full eclipse occurs when a new moon passes between the Earth and Sun and casts its shadow upon the Earth. Where this shadow falls depends on a series of variables involving the intricate gravitational ballet between the earth and the moon (the moon’s orbit, for instance, tilts five degrees more than Earth, so its shadow often falls into open space above or below Earth).

Suffice to say, total solar eclipses are rare, as suggested by Illinois’ 148-year drought.

Because the Earth and moon are in motion, the moon’s shadow traces a line or arc across the surface of the Earth. A total eclipse is visible within this shadow belt, though “totality” (the period when the moon completely obscures the sun) lasts but a few minutes.

For the 1869 eclipse, the path of totality (or “belt of obscuration” in 19th century parlance) moved across Alaska and western Canada, entering the continental United States in the Montana Territory. From there, arcing southeast, it passed through the Dakota Territory and the states of Nebraska, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky and North Carolina. A partial eclipse was visible throughout North America.

The band of totality in Illinois was some 195 miles in length, north to south, reaching as far north as the Illinois River community of Lacon, the seat of Marshall County, and as far south as Pinckneyville, the seat of Perry County.

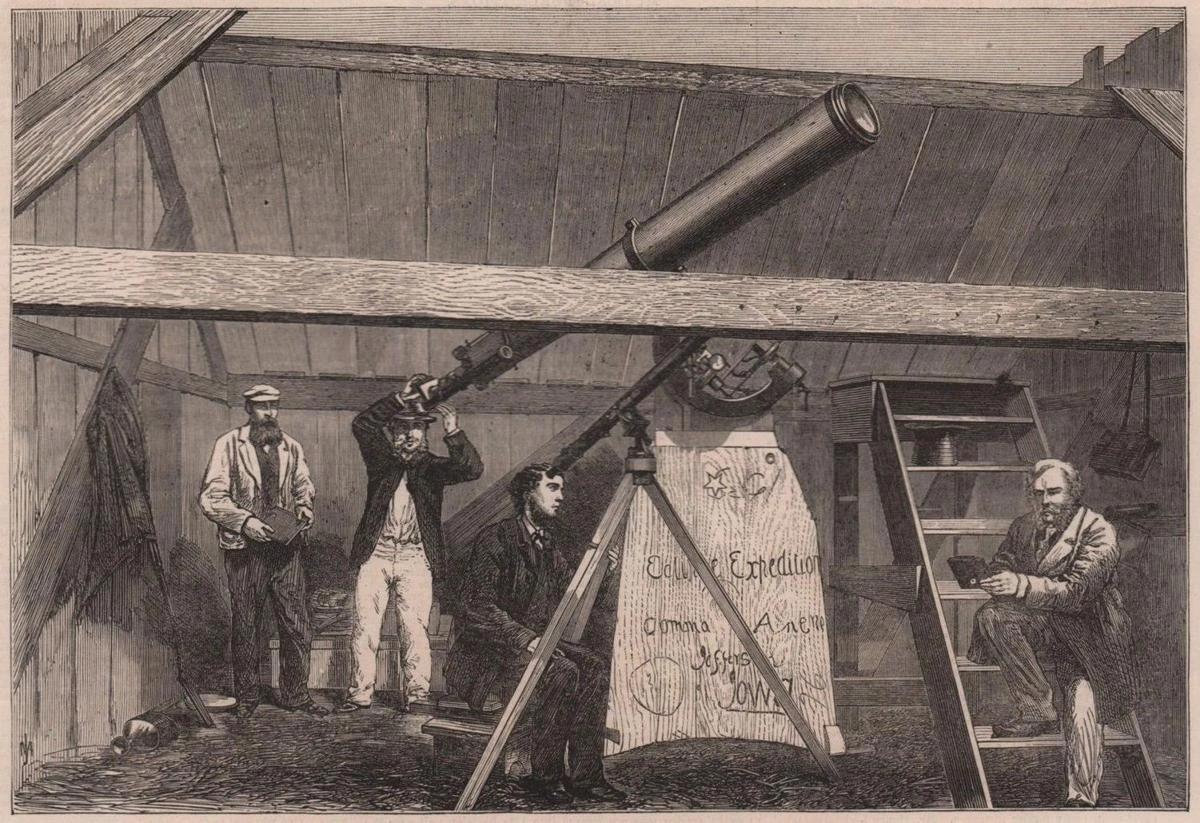

In Illinois, the centerline of the path of totality ran from Macomb to Springfield and then Shelbyville. Several months before the event, Prof. W.W. Austin of the Smithsonian Institution and a team of assistants arrived in Springfield to locate the exact line of totality, with the goal to establish a scientific post to observe and collect data on the eclipse. Austin fixed the line some 150 west of the dome of the still under-construction Illinois State Capitol. A square shaft of marble inscribed with the longitude and latitude coordinates was later sunk to mark this location.

Bloomington was a little more than 60 miles north of the centerline, though still within the path of totality. The eclipse began at 5:03 p.m. in Bloomington, concluding at 7:02 p.m., almost one hour before sunset. Totality commenced about 6:04 and lasted two minutes, five seconds (these figures are courtesy of the all-knowing Carl Wenning, secretary of the Twin City Amateur Astronomers, and Illinois State University Planetarium director from 1978 to 2000).

In 1869, Pantagraph editor Edward R. Roe, a former professor of natural sciences at Illinois State Normal University, published his careful observations of the total eclipse two days after the event. The scientifically minded Roe’s aim was to “put on record” a detailed description of the eclipse as it appeared in Bloomington. He watched the event unfold through a piece of smoked glass from a vantage point somewhere downtown, likely from a roof.

“At four o’clock and ten minutes p.m., by a watch set to Chicago time, the eye detected the first contact of the moon’s southeastern margin with the northwestern edge of the sun’s disk,” recorded Roe. “For the first half hour there was nothing remarkable. Then a deficiency of light began to be manifest, and some tendency to a gloominess. Prairies and groves in the distance were still distinct, but there was no glow upon them. Ten minutes later there was a lurid moonlight look to the sky, which rapidly increased, up to the moment of totality.”

The deepening gloom perplexed the animal kingdom. “Pigeons whirled in aimless circles through the air and settled on the housetops in rows, with wing and plumage drooping,” described Roe. “At ten minutes to five o’clock, chickens began to go to roost; and at five o’clock lightning bugs left their retreats beneath the bushes, and began to emit their tiny lights.”

But what was happening within the immediate environs of downtown Bloomington was of fleeting interest compared to the spectacle far, far above. “As the moon was about to pass fully over the face of the sun, the unobscured portion appeared to flash and scintillate, like molten iron, but with a color like that of gold,” observed Roe. “And at five o’clock and twelve minutes a spontaneous shout went up on all sides, announcing that the eclipse was total.”

The difference in the times cited by Roe compared to those by Carl Wenning, even accounting for the hour difference, is likely explained by the imprecise nature of 19th century timekeeping, especially involving amateurs recording astronomical events.

“One minute and 56 seconds after the eclipse had become total, the sun flashed out on the northwestern margin, with a grand explosion of light, wholly indescribable,” continued Roe. “Another shout went up from the people who filled the streets; and the grandest exhibition of heavenly phenomena ever witnessed passed its acme.”

A correspondent for the Cairo (Ill.) Bulletin traveled to Effingham to view the totality. “A large number of persons had arrived per rail, and many strangers were in town from the country,” noted the reporter. “One old gentleman, over 70 years of age, and one of the earliest pioneers of Illinois, insisted that there would be no eclipse, because he said it was impossible for any person to foretell such things”

Language proved inadequate to the task of adequately describing the beauty and power of the total eclipse. “The minutest report will utterly fail to impress the minds of those who did not actually witness the total obscuration, with a realizing sense of the awful sublimity of such as occurrence,” noted the Effingham correspondent.”

A transcendent scene unfolded in Quincy, Ill. during the height of the eclipse. A funeral procession found itself on Main Street, nearing Sixth, at the moment of totality.

“As the light faded, the solemn procession halted in the street, and while yet the city was enveloped in partial darkness, a prayer was offered up,” read an account in the Quincy Whig newspaper. “As the light burst upon us from the sun the procession moved slowly on, while those composing it began singing a funeral chant. The scene will not soon be forgotten.”