One would be hard pressed to come up with a more iconic image of the Corn Belt than the old wood barn. It’s also an endangered remnant of a lost world, as the number of 19th and early 20th century horse, dairy and cattle barns has been in steep decline for the past half century or more.

But unlike the bald eagle, it’s unlikely the endangered wood barn will ever make a comeback. As their numbers dwindle, saving them has drawn increased attention from farmers, preservationists, and folks who just love the beauty of these sentinels of the Central Illinois countryside.

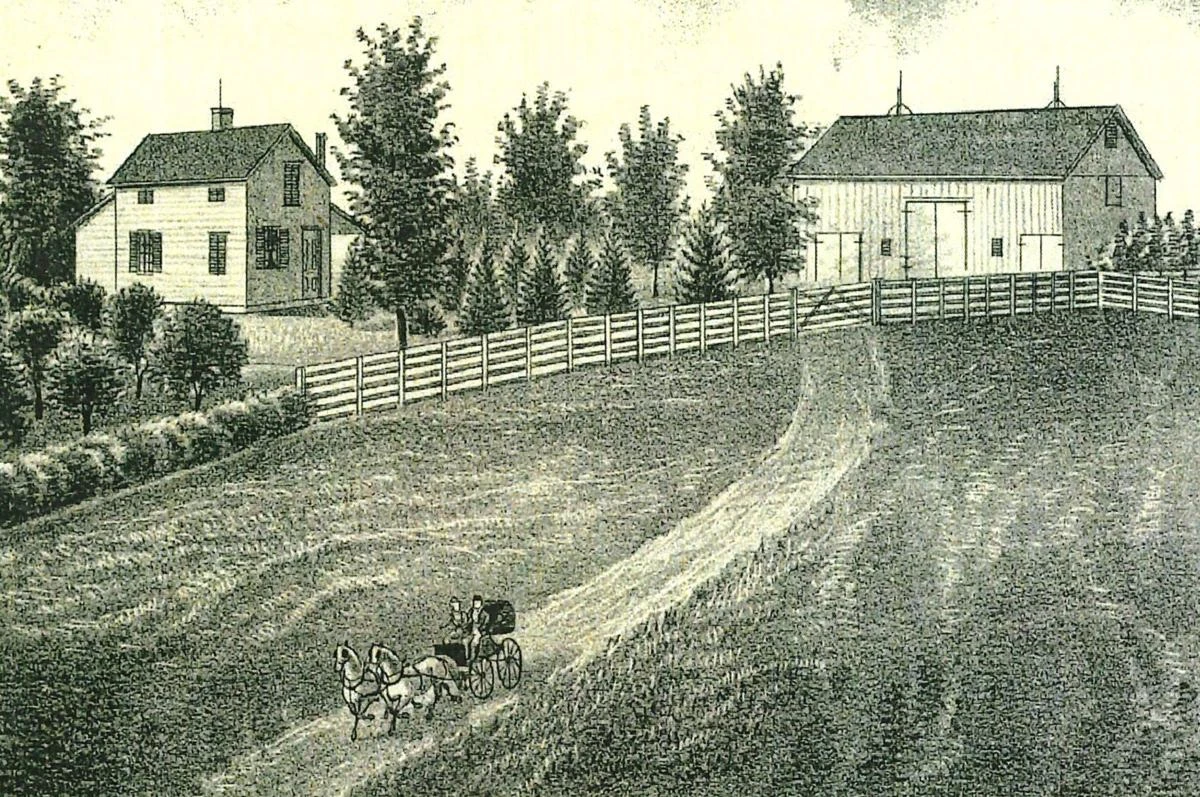

There are various ways to assess the loss of barns in McLean County. For example, there are 50-plus detailed illustrations of local farmsteads in the Atlas of McLean County, published in 1874 (see accompanying illustration), and some 90 such views in the 1887 Portrait and Biographical Album of McLean County. Yet of the several hundred barns depicted in these two works, only a handful—if even that—remain standing today.

Generally speaking, the 19th century barn housed horses and other livestock, but also served as a granary, storehouse, and workshop. Such all-purpose farm buildings were well-suited to the diverse nature of farming back then.

What then happened to these barns, as well as the hundreds upon hundreds of others built in the first half of the 20th century? Well, most fell prey to their own obsolescence, in that they proved ill-suited to the cold efficiencies and brute power of the machine age and cash grain farming.

Mother Nature, though, has also had her hand in bringing down plenty of barns over the years. Tornadoes come naturally to mind, though lightning strikes were long the single greatest threat to farm buildings.

To cite a representative example, on the night of June 11-12, 1929, lightning from a severe thunderstorm claimed a substantial barn on the P.R. Nord farm four miles southwest of Bloomington. Losses, which included tools, machinery, harnesses and “large quantities” of hay and straw, were estimated at $10,000 (or the equivalent of more than $143,000 today, adjusted for inflation).

Although lightning played a dramatic—dare we say electrifying?—role in the loss of barns, of far greater consequence, as mentioned above, were the sweeping changes entailed in the mechanization of the Corn Belt. With the disappearance of horses by the 1940s, and the arrival of ever-larger machines, especially corn pickers and then combines, many old barns became obsolete. Their low ceilings, small doors (comparatively speaking), built-in stalls and other features proved ill-suited to modern industrial-scale farming.

Pole barns and machine shed now dominate the Midwestern countryside, and although they are indispensible to the continued success of Corn Belt farming, they lack the individuality and often simple beauty of their older counterparts.

The loss of area barns in the latter half of the 20th century can be measured with some degree of accuracy. In 1955, the Loree Co. published a reference work titled This Is McLean County, which features more than 700 pages of aerial views of most every farmstead in the county (other counties, such as Livingston and Woodford, received the same treatment). By totaling up the number of barns depicted in this book (and leaving out corn cribs, silos, machine sheds and other larger outbuildings), one learns that there were something like 4,500 barns in McLean County in the mid-1950s.

In 2002, Barn Keepers, a local not-for-profit organization dedicated to the promotion, documentation and preservation of area barns, traveled to every corner of McLean County with the purpose of counting and photographing each and every barn in the county. The decline in the number of barns since 1955 was staggering. Barn Keepers counted 1,200 barns in 2002, a decline of almost three-quarters in less than a half century.

In addition, dozens of barns have been lost since the 1950s when Bloomington-Normal began gobbling up acre upon acre of surrounding farmland for seemingly unchecked commercial and residential sprawl. It’s even happened in the smaller towns. In the spring of 1990, a backhoe unceremoniously razed the lovely Schertz barn on the east edge of Danvers. Erected around 1925, the dairy barn featured glazed ceramic tile half walls and a matching tile silo. The barn was torn down to make way for the new Briarwood subdivision.

The National Barn Alliance views old barns as “cultural resources and heritage assets that are vital to understanding the history of our nation … irreplaceable and worthy of preservation.” There are local groups who embrace this philosophy, including the Barn Keepers and the good folks at the Barn Quilt Heritage Trail—McLean County.

Barn restoration, though, is difficult and expensive, and most farmers are understandably too busy to confront all the potential impracticalities—financial or otherwise—entailed in such efforts. That said, no one treasures old barns more than farmers, as they usually grew up working in them, all the while listening to their parents and grandparents tell stories about them—what they were used for, how that use changed over time, and even the playful mischief and occasional misfortune that occurred in and around them.

Although the need is great, there is little public or private money available to help farmers and other owners save their barns. There’s a federal income tax credit for barn rehabilitation, for instance, but the barn must have been in use prior to 1936 or registered or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. And this tax credit only pays for a percentage of the rehabilitation costs. Given that the price tag for restoring a single barn can easily reach into the tens of thousands of dollars (if not six-figure territory) even well-intentioned programs are non-starters for many barn owners.

Lacking big bucks for preservation grants and the like, groups like the Bloomington-based Barn Keepers often concentrate on educating the public about the need to preserve old barns. Along those lines, the Barn Keepers annual barn tour is Sat., Sept. 9, from 9 a.m. to 4:00 p.m., out and about Hudson Township. Registration begins at 9:00 a.m. at the Hudson United Methodist Church. Tickets are $15 per car for Barn Keepers members, and $20 for non-members. This is the group’s eleventh annual tour in McLean County.

Tour participants will receive a booklet with information on each barn, as well as a map to make sure no one gets lost! Upon registering, tour participants are on their own and free to visit the farms at any pace, and in any order, they choose.

In 1955, Hudson Township was home to around 165 barns. The 2002, the Barn Keepers survey turned up only 37. And in the decade-and-a-half since then there have been additional losses.

Such dire numbers and the future they foretell led one local resident to ask a Barn Keepers board member just how long they’ll be able to keep staging their annual barn tour. In a decade or two, it was asked, will there be enough barns around to hold a tour?