For much of its first 100 years, Bloomington’s formerly unreliable water supply threatened to hold back the city’s growth and industrial development. Pumped from a string of relatively shallow wells, the water was highly mineralized, making it one of the hardest and most unpalatable municipal supplies in the state. The city also struggled to pump enough to meet industrial and residential demand, and water shortages, especially in the summer months, were not uncommon.

Although local government and business leaders long fretted over the city’s water woes, it wasn’t until 1920 and a deadly typhoid epidemic at the Chicago & Alton Railroad Shops that the issue squarely became one of life and death. This outbreak lent much-needed urgency to solve the costly and technically difficult problem of establishing a safe, secure, and long-term supply. In the end, the answer was the creation (in 1929-1930) of Lake Bloomington, a reservoir that continues today to slack the city’s thirst.

Typhoid, caused by the bacterium Salmonella Typhi, is often contracted when sewage contaminates drinking water. A three-year epidemic in the early 1890s in Chicago claimed almost 4,500 lives. For decades typhoid was a frequent and often deadly visitor to Bloomington, though the early 1920 outbreak was likely the largest in city history.

From January through March 1920, tainted water sickened about 800 C&A shopmen, according to an estimate by the Illinois Department of Public Health. Most suffered from serious (though nonfatal) intestinal ailments, while a small percentage came down with full-blown typhoid. In the end, the three-month epidemic left 24 dead.

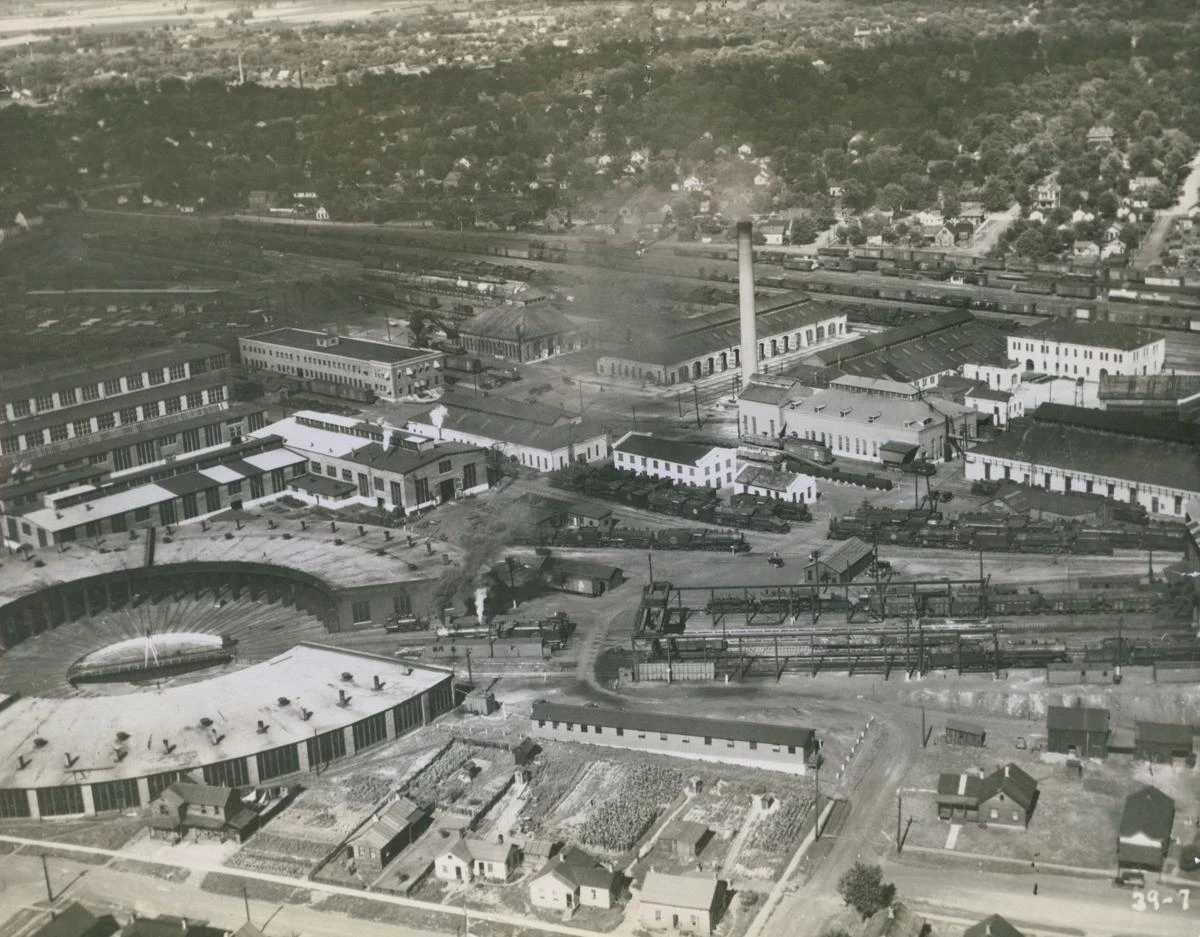

Beginning in the post-Civil War years, the westside C&A Shops were the city’s largest employer. At the time of the outbreak there were some 1,200 men building and repairing steam locomotives and rolling stock, from boxcars to cabooses. The sprawling facility included a roundhouse, locomotive repair shop, foundry, paint shop, wheel and axle shop, powerhouse, offices and rail yards. There were blacksmiths, boilermakers, machinists, carpenters, upholsters, sheet metal workers, crane operators, painters and others.

Bloomington had only recently established the position of health director, and it was readily apparent that Dr. J.M. Furstman had neither the staff nor budget to tackle an outbreak of this magnitude. The first cases were reported in January, and early on some thought that the “Alton sick” (as it was called) might be influenza.

However, an increasingly large number of shop workers bedridden with severe diarrhea caught the notice of Furstman and he began an investigation on or around February 10. At the time, the Bloomington Daily Bulletin newspaper reported that 300 C&A employees were “off duty,” either sick or caring for sick family members. Even at this early point in the outbreak, city officials and the local press knew well enough to suspect polluted drinking water as the source of the problem.

Those who succumbed to the outbreak were mourned. On Sunday, February 15, the funeral for 52-year-old C&A blacksmith Richard J. Kelly was held at St. Patrick’s Church. Rev. M.J. O’Callaghan held services, and The Bulletin reported that it was the largest funeral in quite a while at the Irish Catholic parish on the city’s working class west side. “Throughout the vast industrial plant,” the paper eulogized, “there is genuine regret in the realization that Dick Kelly will no more don his apron at the blacksmith forge where he had worked so many years.”

The state health department arrived at the C&A Shops around February 17, quickly realizing that the widespread incidence of diarrhea pointed to a looming typhoid epidemic. Many workers were experiencing intermittent or acute dysentery, vomiting and fevers as high as 104 degrees. Four C&A workers died between the night of Saturday, February 21, and the following day. The dead included boilermaker Harry Granbeck and machinist John Carlson. By the end of that weekend the death toll had reached seventeen.

The state conducted two postmortem examinations in early March and confirmed the existence of typhoid. By the end of the month, 22 C&A employees were dead, with 15 of those attributed to typhoid and the other 7 influenza or pneumonia, though with the latter group it’s likely bad water was a “contributory cause” of death.

That the shops remained opened even as employees sickened and died speaks to how railroad officials were often grossly negligent when it came to the health and safety of their employees.

To supplement the often-inadequate flow of city water, the C&A relied on what was called the “industrial” supply, pumped directly from nearby Sugar Creek or pulled from wells south of the Shops. In either case, this water was not fit for human consumption, and instead was used for things like toilets, blacksmith slack tubs and locomotive boilers.

State investigators eventually determined that the source of the outbreak was a cross-connection (or what was called an “interconnection”) between one set of pipes carrying city water and another carrying the industrial supply. The culprit was a leaky four-inch valve that was supposed to separate the good water from the bad.

Even after identifying the source, C&A management dragged their feet on correcting the problem. On March 15, infuriated C&A employees walked off the job, insisting on a new set of pipes to ensure the safety of the water supply. “Such conditions cannot be tolerated by any person, whether he be a minister, mayor, or mechanic,” read a statement by labor leaders to the public, “and so we respectfully solicit the help and moral influence of our fair-minded citizens, to the end that such conditions and the causes of the same be justly dealt with and eradicated from this community.” Striking workers held up a passenger train in front of C&A General Superintendent W.H. Penrith’s office, and it’s said they followed that up by chasing him out of tow!

The strike ended March 24 after C&A President W.G. Bierd agreed to install new drinking water pipes entirely separate from the industrial supply, though he balked at the demand to sack two C&A officials who labor leaders believed were most culpable in the outbreak.

In early June, the railroad was ready to settle claims brought by sickened workers and family members who lost a husband, son or father. Hearings before Daniel J. May, arbitrator for the Illinois Industrial Commission, began June 8. For death claims, May generally awarded $3,500 (or nearly $43,000 in today’s dollars, adjusted for inflation) to C&A widows, with an additional $250 for each minor child or dependent.