One of the more striking modern day conveniences we take for granted is the ease of long distance travel. Before commercial airlines, concrete highways and railroads, there were stagecoach lines.

What now takes hours would take days as stages, pulled by teams of four and sometimes six horses, bumped to and fro down impossibly rutted “roads,” waded through seemingly bottomless mud, crossed low-lying prairies transformed into shallow lakes, and forded roiling, swollen streams.

Writing in 1910, local historian Dwight E. Frink noted that the stage era was short-lived in Illinois. The latter 1840s marked the “palmy days” of the stage in the Prairie State, but the emergence of “Titan power” (that is, the steam locomotive) marked the beginning of the end for long-distance travel by flesh-and-blood horsepower.

Throughout the settlement period, most pioneers journeyed by wagon or horseback. Stagecoaches, however, filled a transportation niche for businessmen, visitors from the East, elected officials and others. Stage lines were also the primary carrier of U.S. mail.

In Bloomington, the main stage route ran east-west, from Danville to Peoria and / or Pekin. Before railroads, stage and steamer lines were often linked. The Pekin wharf, for instance, gave travelers access to not only navigable stretches of the Illinois River, but the Mississippi and Ohio rivers as well.

The main Chicago-to-St. Louis stage line bypassed Bloomington in favor of Peoria. That said, there was local stage traffic running north-south that connected Bloomington with either Decatur or Springfield, though service to those communities was irregular.

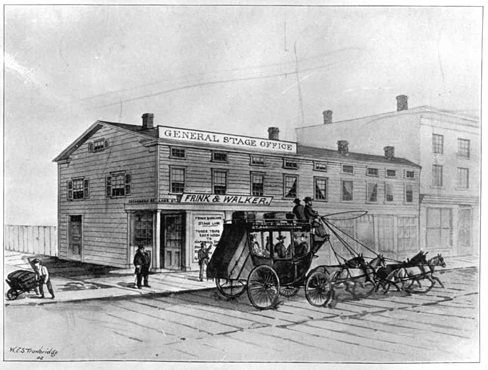

The most dominant Midwestern stage line was Chicago-based Frink & Walker (later Frink & Co., sans Walker). Formally established in 1840, John Frink (no known relation to local historian Dwight Frink) and Martin Walker’s company operated a main terminal at the corner of Dearborn and Lake streets in downtown Chicago.

In late July 1851, The Weekly Western Whig, a Bloomington newspaper that predated The Pantagraph, announced that Frink & Co. was now running a “splendid” stage from Bloomington to Urbana, and that westbound service would now run directly to Pekin, rather than first stopping in Peoria. “Persons now coming from Ohio and Indiana, will find this route the most direct, convenient and comfortable one that now crosses this state,” read the notice.

Frink & Walker sometimes faced competition from local operators. One early settler remembered Bloomington Judge John E. McClun wresting away the Danville-to-Peoria mail contract from a stage line (presumably Frink’s). There were also local freight haulers, like Bloomington’s William G. Boyce, who served as over-the-road truckers of the pioneer era.

Stagecoach bodies were supported by leather straps, known as “thoroughbraces,” that served as shock absorbers. Many stages that crisscrossed Illinois were nine-passenger, four-horse “post coaches” manufactured by Abbot and Downing of Concord, NH. These coaches could accommodate a tenth passenger—if they didn’t mind riding atop with the driver! According to historian Dwight Frink, the first “real coaches” in Bloomington (“swung by four massive straps above a sturdy gear”) appeared in the late 1840s.

Travel conditions were unpleasant at best and appalling at worst, and the trials and tribulations of stage passengers is a lively sub-genre of frontier literature. For example, a July 16, 1836 letter (written in Latin but later translated into English) by Jesuit Father Pierre Verhaegen to his superior in Rome detailed a dreadful (though altogether unremarkable) stage trip from St. Louis to Springfield.

Father Verhaegen’s six-seat coach, crammed with nine passengers, was no match for a prairiescape dotted with stagnant water. The riders, already tormented by gnats, had to disembark and “proceed on foot through horrid places if they would not see the coach sink in the mud.” And at a crude wayside, eight men, including Father Verhaegen, shared four beds in a 20x20 foot square room.

Traveling one night, the stage hit a steer lying in the road. When the wounded steer’s horns became entangled in the reins of a tripped-up horse, the near-disaster of a runaway stage was averted only when passengers leapt from the topsy-turvy coach to steady the “foaming steeds.”

J.S. Buckingham, in his multi-volume travelogue published in 1842, recounted a stage stop twelve miles out of Chicago. During the change of coaches, he recounted, “we had to wait in the bar-room of one of the most filthy and wretched houses we had yet seen … the hideous-looking bar-keeper appeared like a man who never washed or combed, and none of whose garments had ever been changed since he had first put them on;—altogether nothing could be more revolting.”

William H. Milburn, a blind Methodist preacher, recalled an 1846 journey from Chicago through Peru, Peoria, Bloomington and beyond. Eleven miles east of “Peory,” with Milburn and his wife the sole passengers, the stage company swapped out its four-horse coach for an uncovered two-horse wagon.

Once in Bloomington, Milburn inquired as to hotel accommodations. The driver “assured us that we should get nothing fit to eat,” he recalled, “and that if we attempted to sleep, the bed-bugs would eat us up.” Milburn wisely directed the driver to continue “to the door of the Methodist that lived in the largest and most comfortable house.”

The Vale livery stable, located at the northeast corner of East and Front streets in downtown Bloomington (today this site is a surface parking lot), served as a local stage stop in the 1840s, if not a little later. The East Street portion of stable dated to 1846 and the Front Street addition to 1852.

In early June 1879, The Pantagraph reported that the two attached buildings, “swaybacked and sprung like old steeds,” would soon be torn down. “Many an exciting scene have they witnessed, and many a thrilling story have they heard related,” mused The Pantagraph of the two buildings. “They have had their day, and are now to pass into the oblivion which has hidden from the world thousands whose footsteps often echoed within their walls.”