The McLean County Museum of History, as part of its Presidents Day activities on Monday, will have on public display its recently acquired Abraham Lincoln letter.

The 160-year-old historically invaluable letter was addressed to Kersey H. Fell of Bloomington, and involved a debt collection case, Fell being a defendant (or debtor) and Lincoln the attorney for the plaintiffs (or creditors.)

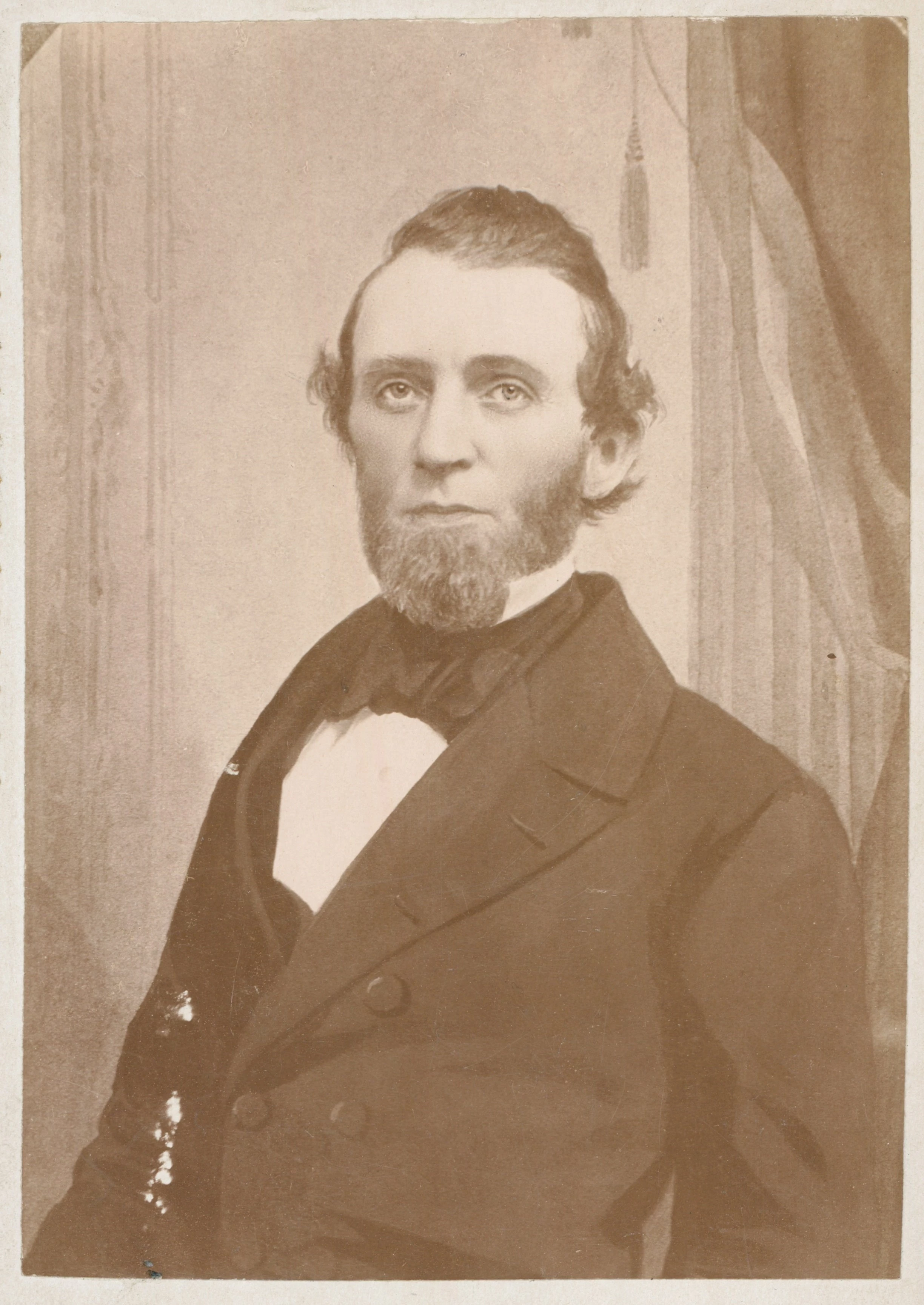

Kersey’s older brother Jesse W. Fell made a long and lasting imprint on what would become the Twin Cities, playing a central role in getting the state to locate its first public university in Normal, among other accomplishments. In 1836, Kersey followed Jesse to Bloomington, and like his brother, he became an attorney only to leave the law “in favor of the more congenial work of buying and selling land.”

Although on opposing sides on this breach of contract case, Abraham Lincoln and Kersey Fell were political allies and acquaintances, what with Lincoln’s extended visits to Bloomington as an attorney on the 8th Judicial Circuit. In fact, he was known to frequent Kersey Fell’s office, located in an upper floor of 106 W. Washington St., a four-story brick Italianate commercial building dating to 1856. That building still stands, and today Burpo’s Boutique occupies the first floor.

At some unknown date, likely in the mid-1850s, Kersey Fell and a second individual, identified only as Price, gave Quincy law partners Orville H. Browning and Nehemiah H. Bushnell a promissory note. Upon failure to pay the note, Browning and Bushnell retained Lincoln to sue Price and Fell in an action of “assumpsit” (meaning to recover damages for a breach of contract.)

In ruling for Browning and Bushnell, the McLean County Circuit Court awarded $370.82 in damages (or roughly the equivalent of $10,000 today, adjusting for inflation.).

The 7½ by 9½ inch fully authenticated letter now in the museum’s collections, dated Nov. 1, 1859 from Springfield, was written after the circuit court ruling and when Lincoln and Fell were negotiating on a payment schedule for the judgment. “My dear Sir,” Lincoln wrote in his unaffected cursive script. “I know not that I shall be at Bloomington soon. I shall be here till Tuesday next; and will be glad to see you.” The letter is signed, “Yours very truly, A. Lincoln.”

Brief and businesslike though it may be, this letter wonderfully exemplifies Lincoln’s career as a general practice attorney in litigious antebellum America. In a legal career that spanned nearly a quarter century, he handled more than 2,300 cases involving breach of contract. In fact, debt collection represented about half the caseload of Lincoln’s entire bustling practice.

The lack of hard currency, especially in still-developing states such as Illinois, led to the proliferation of promissory notes, which helps explain why debt collection cases were common in Lincoln’s time. These notes, convoluted by their very nature, were often exchanged and renegotiated by a succession of parties. Add to that the era’s boom-and-bust economic cycles of shady development schemes, real estate bubbles and bankruptcies, and it’s no wonder debt-related cases filled the courts.

Our understanding of Browning and Bushnell v. Price and Fell is aided by additional letters and court documents, though these are not held by the McLean County Museum of History.

“When I went to Bloomington,” Lincoln wrote on Jun. 29, 1857 to his client, fellow attorney Orville H. Browning of Quincy, “I saw Mr. Price and learned from him that this note was a sort of ‘insolvent fix-up’ with his creditors—a fact in his history I have not before learned of.”

Much like Lincoln, Browning was a former Whig Party stalwart who joined the anti-slavery Republican Party when it formed out of the latter’s ashes in 1856. Five years later, in 1861, the Republican governor of Illinois appointed Browning to fill the U.S. Senate vacancy left by the death of Stephen A. Douglas. Living in Washington D.C. during the Civil War then, Browning became a frequent visitor to the Lincoln White House.

Back in 1859, the court ruled for Browning and Bushnell on Apr. 6. Kersey Fell was unable or unwilling to come up with the full $370.82 judgment, so he put forward a payment plan in a May 20 letter to Lincoln (why Price was apparently no longer party to the judgment is not known.)

After waiting more than a month for a response, Fell wrote once more to Lincoln. “I now propose to pay you a part of the judgment—say $150 dollars and the bal[ance] in a year from the date of the judgment,” reads his Jul. 8, 1859 letter. “I would gladly pay it all off now but I can’t do it. Please do let me hear from you in reply and say when you will probably be at home as I want to consult with you about some business matters soon—your friend.”

Lincoln replied the following day, accepting Fell’s proposal and ending with this: “Think I will see you at Bloomington in two or three days. If not I will write again. Yours as ever.” The letter the museum now holds is a follow-up to this one of Jul. 9, 1859.

Whether Fell paid the judgment in full and on time is not known, though there is no record of subsequent legal action to indicate such.

As a not-for-profit historical society, the McLean County Museum of History relies primarily on donations from local residents, groups and businesses for its collections. In the case of the Lincoln letter, retired attorney, Lincoln scholar and museum board member Guy Fraker worked with Sharon Merwin of the Merwin Foundation, which agreed to purchase the letter on behalf of the museum. Guy said the gift is testament to the Merwin family’s continuing commitment to McLean County, and speaks to the legacy of Sharon’s late husband Davis U. Merwin, who was the publisher of The Pantagraph.

The museum’s “Presidents Day: The Vote” activities run tomorrow from 12 noon to 3 p.m. at the old courthouse in the heart of historic downtown Bloomington. There will be plenty of fun and educational activities for children of all ages, and a chance to “vote” in a mock election using actual Bloomington Election Commission equipment. In addition, you’ll have the opportunity to visit the Connect Transit Community Bus to meet many of the candidates running for Normal and Bloomington council seats in the upcoming April election.

Lincoln’s Nov. 1, 1859 letter to Kersey Fell will be on display in the museum rotunda from 12 noon to 7:00 p.m.

When Guy Fraker brought the framed letter to the museum several weeks ago, he parked on the south side of the square at the museum’s main entrance. Guy said that by chance he glanced across Washington Street when getting out of his car, and it occurred to him then and there that 160 years ago this very letter was undoubtedly read by Kersey Fell in his office, which was right across the street!

It is rare moments like this when one is privileged to experience the miraculous—if not mystical—melding of the past and present, and history comes alive.