On the western edge of downtown, the no-frills, mom-and-pop Butler House was an old friend to the weary traveler and local resident alike. The hotel doubled as an economy boarding house, so its ambiance was always more welcoming, working class and west side than its more stylish downtown competitors.

For some 35 years, John Preston “Press” Butler, his wife Elizabeth “Lizzie” Kavanaugh Butler and their adult children owned and operated the place, which also served as their family home.

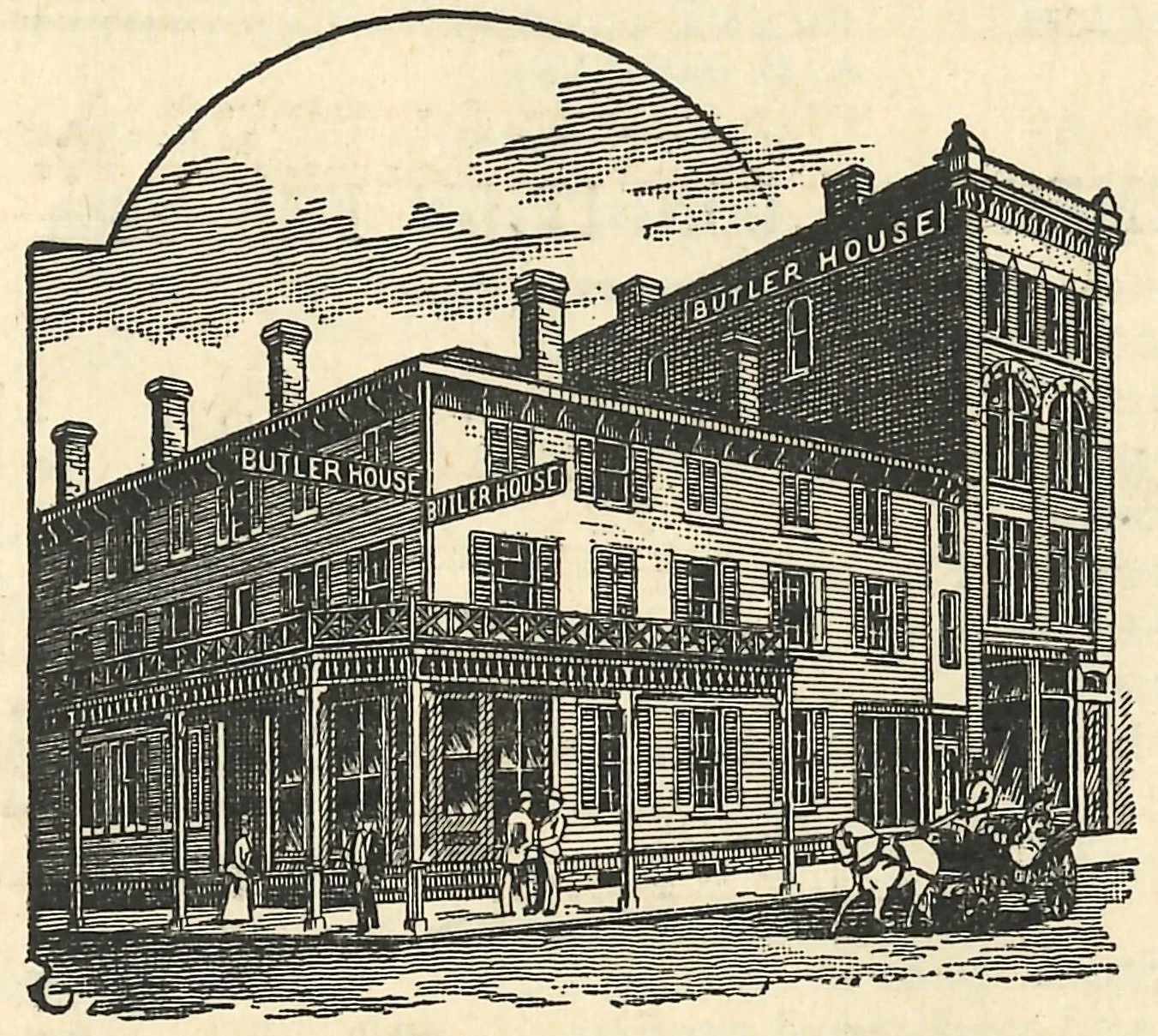

Located at the northwest corner of Madison and Front streets, the three-story, wood-frame hotel already had a rich history before the Butlers came into the picture in the mid-1880s. It appears the hotel opened for business way back in 1856 or 1857, in the decade before the Civil War, and was first known as the Bronson House and then the Denman House.

In its early years, the hotel regularly changed hands, and for a long time it was known as the St. Nicholas Hotel. Press and Lizzie Butler began running the hotel in 1884-1885, changing its name from the Wait’s New Hotel (its most recent incarnation) to the Butler House

In the latter half of the 19th century there were few Bloomington residents as intriguing as Press Butler. “He weighs not over 130 pounds, is short in stature, and of slender build, with black hair and eyes, and a swarthy mustache and goatee,” noted The Pantagraph. “He is the impersonation of self-reliance, grit, and cool courage. His nerve and pluck have been tested time and again, and have never failed.”

Butler first gained a local reputation as a daring Bloomington firefighter in the era of volunteer companies. By the mid-1880s, he was a private detective of considerable fame. His exploits included a lengthy gun battle at Bloomington’s west side Union Depot ending in the capture (and eventual conviction and imprisonment) of a “notorious forger and safe-blower.”

In 1888, the Butlers erected a handsome four-story brick addition to their hotel facing Madison Street. The 24-room north side addition was designed by Bloomington architect George H. Miller, whose many local buildings include the old Moses Montefiore Temple on Prairie Street, and the Central Fire Station (now Epiphany Farms Restaurant) on Front Street.

With the George Miller addition, the Butler House offered 64 rooms, as well as a “bar, billiard room, and barber shop.” Even so, the original part of the hotel, in all its creaky, wood-frame antebellum glory, meant that the Butler place was never a direct competitor to the larger and finer hotels of sturdy brick in the heart of downtown, such as the Ashley House on the northwest corner of the courthouse square, and the Phoenix Hotel on Center Street between Jefferson and Monroe.

In July 1887, a Hoopeston, Ill., baseball club traveled to Bloomington for a scheduled game against the local “nine.” It was the practice back then for the hometown boys to cover the visitors’ hotel and traveling expenses. “They stopped at the Butler House, but desired a high-priced house, and accordingly moved to the Phoenix,” recounted The Pantagraph. “The Bloomington management refused to pay the difference, and the ‘Hoopestons’ paid their own bill and left the account in the hands of [McLean County] Judge [Colostin] Myers to collect.”

Perhaps because of its well-worn appearance and casual atmosphere, the Butler House had a reputation for attracting colorful characters. In early Dec. 1893, for example, circus great William Sparks, aka the “American Hercules,” “breathed his last” in one of the rooms. Sparks, known for the “cannon ball act,” traveled with Barnum, Ringling and other top-tier circuses for three decades. According to The Pantagraph, he developed a morphine habit six years earlier after being horribly burned during a performance mishap. Sparks had been staying at the Butler House for about a week with his daughter after failing to free himself of his addiction at the Keeley Institute in Dwight, Ill. His death made The New York Times.

The Butler House also served as the stage for some wild scenes, more than a few involving fisticuffs, knives, firearms, or, on at least one occasion, a hefty chunk of lumber. In April 1916, two “obstreperous” amateur boxers, John “Chick” Hayes and Jimmie Gardner, caused a ruckus in the Butler House parlor until they met their match in Capt. (later known as “Major”) E.C. Butler, one of Press and Lizzie’s sons. Wielding a “sap,” Butler knocked one of the pugilists across a chair, and the two troublemakers spent the night in jail, charged with drunkenness and disorderly conduct.

Press Butler died on Jan. 28, 1918 at the age of 79. The following fall, Lizzie Butler and her son Major E.C. Butler and his family, all of whom had been living at the hotel / boarding house, moved into an apartment building on North Main Street. They then “rented out” the family business, and in its final years the Butler House became known as the Butler Hotel.

After the move, Lizzie Butler lived a few months more before passing away on Feb. 8, 1920. “Her life was characterized by kindness,” eulogized The Pantagraph. “Few women have been so universally loved and her death has thrown a pall of sadness over the wide circle of friendship, which had spread around her during her long residence in the heart of the city.”

An executor’s sale was held three weeks later, but the bids were deemed too low, so the family decided it best to raze the three-story wood-frame hotel and sell the lot. The four-story brick addition was left standing.

The “historic hostelry” then came down in the summer of 1922, the framing dismantled and carted off for reuse elsewhere. “The hotel is the oldest in the city and is one of the noted landmarks in this section of the country,” reflected The Pantagraph.

A filling station later replaced the Butler House corner, as the periphery of downtown became the increasing domain of businesses serving the automobile—from service garages to dealer showrooms.

The brick addition facing Madison Street remained standing into the 1950s, and the faded letters spelling “Butler House” could be read on its north wall for many years. During the Great Depression the building served as a shelter for the homeless and then became Sheeney’s Tavern.

Between 1956 and 1961, this building and the remaining ones on the southern half of the block bounded Madison, Front, Roosevelt, and Washington streets were razed.

Today, the Butler House lot is an underutilized eyesore; one more surface parking lot in a downtown blighted by them. The Butler name survives into our denuded present because the city-owned space is called the Major Butler Lot, the “Major” part apparently a nod to either one or both of Press and Elizabeth Butler’s sons.

William Butler served as a major in the Spanish-American War, and his brother Edward as a captain, though later on Edward became known as “Major” Butler as well, though whether he officially attained that rank is unknown.