In the years before the Civil War and for several decades afterward, Bloomington’s African-American community embraced alternatives to the Fourth of July holiday.

After all, the triumphant narrative of Independence Day rang hollow to many Black Americans when there were still some 4 million of their brothers and sisters in bondage. And even after the war’s end African Americans preferred to celebrate their independence on days reserved for the singular trials and travails, and hopes and ambitions, of their people.

The biggest African-American holiday in this period was known as First of August, or more generally Emancipation Day, and the all-day affair usually included a procession, afternoon picnic, speeches on the state of Black America, and an evening of music and dancing. The First of August holiday commemorated the anniversary when slaves were freed in the British West Indies, Aug.1, 1834

From available evidence, the first such Emancipation Day was held in Bloomington on Aug. 1, 1859. This gathering also doubled as a fundraiser for the local African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church building fund and Sunday school (this church is Wayman AME today).

Tickets were 25 cents, with discounts for families, and could be purchased at Hiram Underhill’s barbershop across from the American House, a hotel on Front Street. Underhill was African-American, as were most barbers in 19th century Bloomington.

On this summer day in 1859, a procession, likely including the better portion of Bloomington-Normal’s African-American community and a good number of Black folk from nearby towns and cities, assembled at the new AME church on North Center Street and paraded to Major’s Grove, a wooded, park-like spot on the north end of the city.

Nineteen-year-old Edward Joiner, born free in Illinois and barbering for Underhill at the time, made what was said to be his debut as a public orator. Joiner, a future minister (he was licensed to preach in the AME church around this time), “exhorted his brethren to put their own shoulders to the wheel, and improve themselves in knowledge and dignity of character, as an essential means to realizing their aspirations.”

The speaker following Joiner, identified by The Pantagraph as a “stranger from Chicago,” noted the day’s significance as the anniversary of slavery’s abolition in the West Indies.

The First of August celebration of 1862 offered “more than the usual spirit and interest,” occurring as it did in the midst of the Civil War. A former slave identified as E. Hutchens gave the afternoon’s first address. “His style of speaking was plain, forcible, and correct, sometimes bordering on eloquence, but never approaching highfalutin,” remarked The Pantagraph. “He gave a glimpse of slave life, and dwelt at length upon the duty of his brethren in the free states, to educate their children, elevate their moral and religious character, and fit them for the higher position which he dared to hope they would soon be allowed to enjoy.”

After 1870, Emancipation Day was often held at different times of the year. New Year’s Day became a favorite date for two reasons. On Jan. 1, 1808, the federal government banned the importation of slaves into the United States, the earliest day permitted by the Constitution. And Jan. 1, 1863, marked the effective date of Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, which freed slaves in parts of the Confederacy still under rebellion. Sept. 22 also a popular date to hold Emancipation Day, for on that day in 1863 Lincoln first issued his Proclamation.

Other Central Illinois communities, including Clinton, Decatur and Pontiac, held their own Emancipation Day programs (whether annually or occasionally), and when possible a party of Bloomington residents, sometimes numbering 50 or more, would make the trip as a show of solidarity and friendship.

On Jan. 1, 1875, in what was described as the “grandest demonstration ever made by the colored citizens of the city of Bloomington,” Emancipation Day festivities began with a procession from the African-American Baptist church on Lee Street (this church is now Mt. Pisgah on West Market Street) to Phoenix Hall on the south side of the courthouse square.

A second emancipation celebration was held later that year, on Aug. 11, and it included a program and picnic at the old west side fairgrounds. The day-long event, reported The Pantagraph, “was quite well attended and highly enjoyed by our colored brethren of Bloomington and neighboring towns, and also by a number of white persons.”

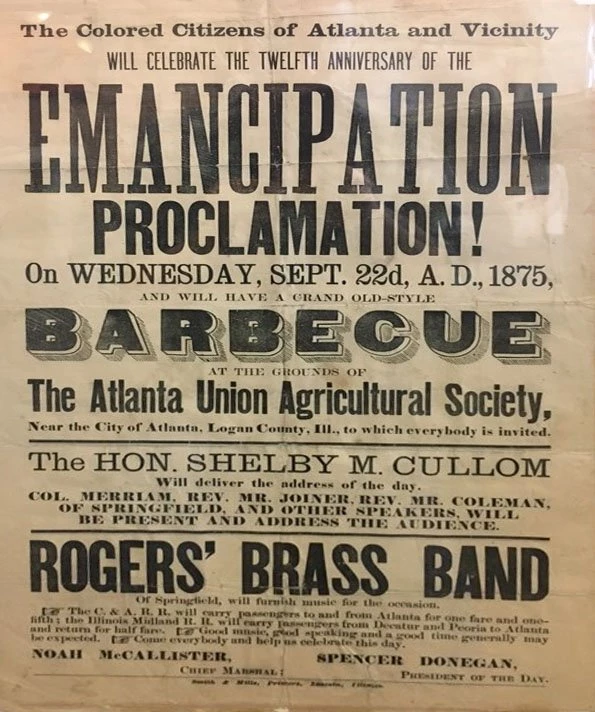

Currently on display at the Atlanta (Ill.) Museum 20 miles south of Bloomington is a poster-size announcement for a Sept. 22, 1875 celebration marking the 12th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation (see accompanying image). The gathering, which included Benjamin Franklin Rogers’ Brass Band of Springfield and a “grand, old-style barbecue,” was held on the Union Agricultural Society grounds outside of Atlanta.

Emancipation Day remained popular throughout the 19th century. In the summer of 1894, for instance, Bloomington’s Miller Park was the site of a large celebration. Swelling the crowd were African-American delegations from Decatur, Jacksonville, Lincoln, Peoria, Springfield and elsewhere.

There were sporadic emancipation celebrations in Bloomington as late as the mid-1950s, though by that time they had taken the form of a picnic for African-American children.

Today, the heir to Emancipation Day is Juneteenth. Sometimes known as Freedom Day, Juneteenth commemorates the announcement, made on Jun. 19, 1865, abolishing slavery in Texas.

On Jan. 1, 1884, the Rev. C.S. Smith of Bloomington’s AME Church delivered a fiery Emancipation Day address at Central Music Hall in Chicago. Less than two decades after the Civil War, the promises of emancipation and reconstruction had, in the face of violence and intimidation, given way to white-only rule, disenfranchisement and segregation.

And what of colored soldiers of the late rebellion, those who “lifted the Stars and Stripes from the dust of treason, and planted [it] on liberty’s universal throne?” asked Rev. Smith. “In times of war they fought to defend and protect the nation’s life, and in times of peace it is the duty of the nation to defend and protect them,” he replied, boldly asserting that a government “powerless to maintain the liberty of its citizens … ought to perish beyond the memory of God and man.”

Smith was uncompromising in his condemnation of the American South and a federal government complicit in denying African Americans basic political and civil rights. “I care nothing about the so-called rights of the states,” he concluded, “when my liberty is jeopardized and my constitutional privileges trampled on and denied.’