“The voice that spanned continents and oceans to win international acclaim is forever stilled,” announced a somber Pantagraph in October 1937.

Was this the passing of a beloved opera diva or Irish balladeer? Well, not quite. Rather, the forever-stilled voice of international acclaim belonged to Mikey, Bloomington’s famous singing mouse.

The Great Depression was a golden era for odd amusements, what with so many Americans eager for distractions from the hard times. During the spring of 1937, singing mice were the latest newsworthy diversion. Minnie, a mouse from Woodstock, Ill., made a national stir by performing live on the radio, gaining a local and national following along the way. Soon, stories of singing mice began popping up across the country.

The saga of Mikey, Bloomington’s very own champion soloist, began during the winter of 1936. That’s when employees for the Vose Cooler Mfg. Co. on the city’s west side began hearing a bird-like trilling in the factory’s nooks and crannies and behind its walls.

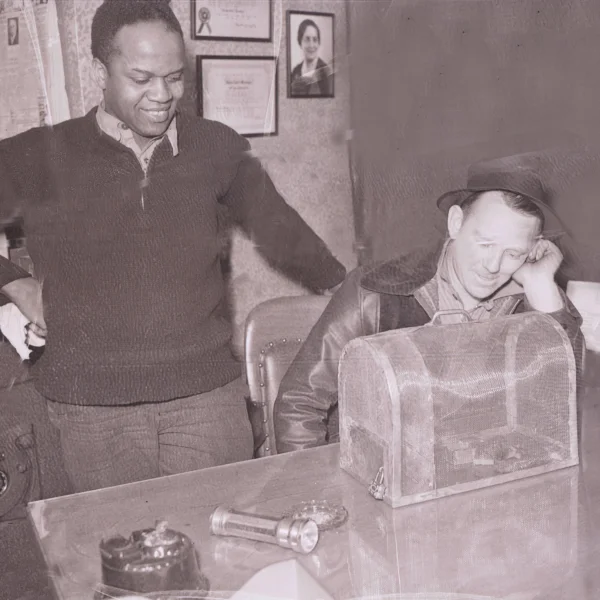

Mice “songs” such as those heard 80 years ago at the Vose manufacturing plant are said to be reminiscent of the “twittering, chirping, whistling or warbling of small birds.” The mysterious, melodious west side mouse was finally captured on New Year’s Day 1937 by business partners W.F. Vose and Jack Karstens. One of the tinners at the plant then constructed a cozy vaulted cage of wire mesh and tin, with a strand of solder running the length of the cage for play and exercise.

Knowing of the recent fame accorded Minnie of Woodstock, Vose and Karstens decided to follow suit with Mickey (as Mikey was first called). The partners, though, didn’t know a thing about show business, so they turned to Gilbert C. Brown, manager of the Irvin Theater in downtown Bloomington. Soon thereafter Vose and Karstens sold their interest in Mickey to Brown, and the theater manager became the roundelaying rodent’s handler, stage manager, agent and publicist.

By all appearances, Mickey was an ordinary gray mouse with a blotch of white on his belly. Today, we know that mice “sing,” though they do so at a frequency well beyond the range of the human ear. Males, for instance, employ intricate ultrasonic vocalizations not unlike birdsong to attract mates.

And while it’s extremely rare, every so often there comes a mouse we humans can hear, though just why is not understood. One researcher involved in this fascinating field speculates that it might be some laryngeal imperfection that lowers the frequency of the vocalizations—low enough to be picked up by us.

Back in 1937, Gilbert Brown saw to Mickey’s first radio broadcasts, as well as a $35-a-week gig in the lobby of a Peoria theater. Mickey also appeared at various events in the Twin Cities—from school activity nights to auto shows. “He sings—he croons—he’s got swing!” read one promotion.

Mickey was kept at the Irvin Theater, which was located on the 200 block of East Jefferson Street (once the finest movie house in the Twin Cities, it was torn down in 1987). Fearing the talented entertainer might be the target of thieves, Mickey and his cage were secreted away to a closet under the theater’s semi-balcony.

On Friday, Jan. 15, disaster struck when Mickey escaped captivity while Irvin Theater janitor Howard Brent cleaned his cage. The diminutive runaway found the theater’s hollow tile walls a perfect place to scurry away and hide. A day or so after the great escape he turned up in the organ pit near the movie screen, still on the lam.

The search riveted the community’s attention. “There was no end of advice as to how to catch Mickey,” reported The Pantagraph. “Numerous theories as to the most succulent foods to be used as bait came in jumbled confusion through the telephone wires.”

After two successive all-night vigils lying silently beside the organ pit, theater employee William Lyons’s patience paid off when he recaptured the furtive fugitive on Monday, Jan. 18, at 7:30 am.

At some point Mickey became known as Mikey, the change likely prompted by the fact that the English champion carried the same commonplace name (common for mice, that is).

In April 1937, the NBC radio network organized a national singing mice competition, with the winner to face several established international stars at a later date.

The April 11 nationally broadcast contest was held in four cities—Chicago, Boston, Memphis and Seattle. A panel of experts listening in from New York rated the dozen or more contestants . Mickey performed in Chicago, from WCFL studios in the American Furniture Mart building on Lake Shore Drive. Thornton Burgess, a conservationist and children’s author, served as master of ceremonies.

Mikey, in an Associated Press news account carried across the nation, “caroled steadily for an hour before the broadcast started, and continued throughout his allotted time on the air.”

Other contestants had their troubles. The Indianapolis entry, for instance, escaped in the studio, and by the time he was corralled he was said to be too nervous to perform. “Naturally he wouldn’t sing after being chased for 45 minutes,” grumbled his handler.

Declared the winner, Mikey had three weeks to prepare for the May 2 world championship against formidable competition—Minnie, the songstress from Woodstock, Ill., and the English, Wales and Canadian champions.

Much like the national competition, Mikey benefited from the disappointing performances (or mostly non-performances) of his competitors. Johnny, the “Toronto Tornado,” remained silent his entire allotted airtime, “and even his trainer’s exhortation to ‘realize it’s for the glory of Canada’ failed to elicit a chirp.” The legendary Minnie was likewise mute before the mike.

Mickey and Prissie, the English and Welsh champs respectively, were “in excellent voice and singing hard,” observed one English commentator. “I thought they’d win.”

Yet Bloomington’s favorite son carried the day by a whisker’s length or more. “Mikey of Bloomington—terrific. A rich, fruity contralto—loud enough for the back rows of the gallery,” noted the commentator, who, in a pique of English stuffiness, added that the “Bloomington boy won, I’m afraid, on volume.”

From Central Illinois factory mouse to international champion in four months!

Alas, fame can’t forestall the inevitable, and the inevitable comes much sooner for mice than it does for men. For Mikey it came on Oct. 8, 1937.

Since June of that year, the furry soloist had been a guest at the rural Plano, Ill. home of Jules J. Rubens, vice president of Publix-Great State Theatres, the chain that owned the Irvin. “There was no post mortem examination,” Gilbert Brown said, “but Mikey was placed in a little wooden box and buried with due obsequies. Some kind of a tombstone will be erected, I presume.”