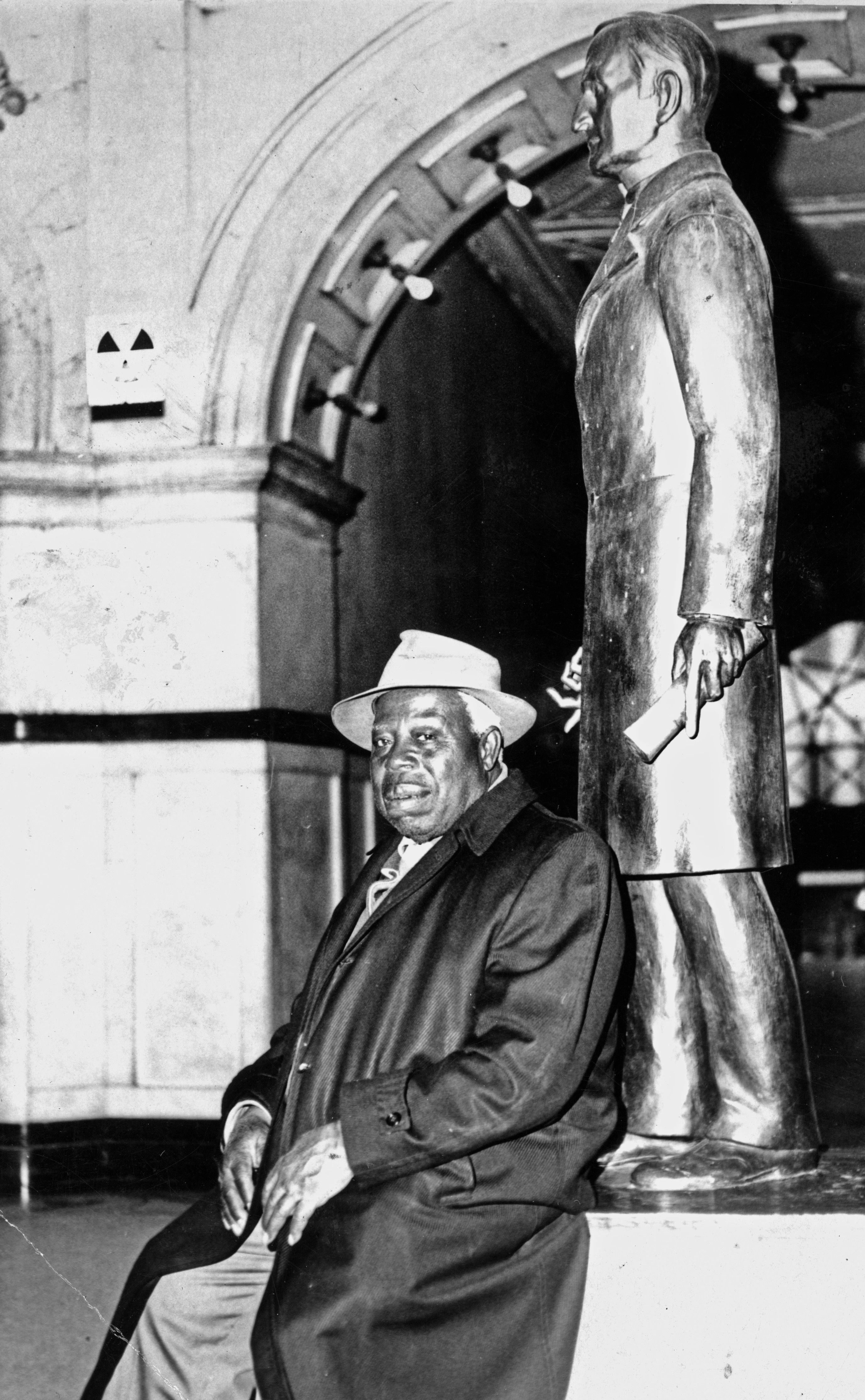

In the 1960s and into the early 1970s, visitors to the McLean County Courthouse would see two figures stationed at the center of the main floor rotunda—Asahel Gridley and Joseph J. Johnson.

Gridley, a key figure in Bloomington’s early history and the city’s first millionaire, had long passed on, his presence represented in bronze, thanks to the efforts of his daughter Mary Gridley Bell.

Joe Johnson, on the other hand, was very much alive.

Whether it was directing a young couple to small claims court or trading afternoon greetings with the circuit clerk, Johnson was as much a Courthouse fixture as the Gridley statue. “I like to watch the people and to get to know them,” he once said. “For those who don’t know me, I can tell them where to go around here.” (Today, the Courthouse is the McLean County Museum of History and the Gridley statue sits in the north hallway.)

Neither county employee nor official greeter, Johnson was simply a retiree trying to keep busy soaking in the hustle-and-bustle of the workaday world. “I’m just meddling, that’s all,” he playfully acknowledged. “He was the best traffic director the Courthouse ever had,” was how his wife Elizabeth put it. Because he seemingly knew everyone, and knew where everything and anything could be found, Johnson was known as “Bloomington’s Human City Directory.”

Joe and Elizabeth Johnson lived on the 800 block of East Walnut Street, and because he had no car, he walked the dozen or so blocks to the Courthouse. “I leave home at 11:30 every day, eat my lunch at Kresge’s [a long-gone five-and-dime store on the Courthouse Square], talk to my friends until they have to leave for work, then I come here and direct people until 10 minutes of 4,” he told a Pantagraph reporter from his Courthouse post in 1971. “Even the people at Kresge’s know me. Some of the waitresses call me ‘Uncle Joe.’”

Born in 1890 in Union Town, Ala., Johnson was the oldest of eleven children and never got farther than the third grade. His grandparents had been enslaved, and Johnson claimed that one of his great-grandmothers had lived to the age of 118. “I left Mississippi for Memphis, Tenn., but I couldn’t stay there because of the railroad strike,” he recalled. “I tried to get work there and I was offered a job that paid $18 a week. I refused when the boss said that I only had to pay $7 for room and board. I said, ‘Yes, but I also have to buy shoes.’ So I left for St. Louis.”

“At the train depot [in St. Louis] a group of us met a man who needed railroad workers,” recalled Johnson. “He told us that he could take us to Bloomington, Illinois, for half fare and that there was no strike. I got a job in the roundhouse until June 1920. At that time we lived in boxcars.”

All his life Johnson earned a living with his hands and back, spending his working years as a janitor and laborer for various employers, including the City of Bloomington, Model Laundry, and the Christian Science Church. From 1955 to 1958 he worked at Illinois Wesleyan University, “where there were 1,000 students who didn’t need directing,” he joked. He also did a lot of yard work around town to supplement his earnings.

Johnson also enjoyed talking about the old days in Bloomington. “It was just like a village, and it was called the ‘Evergreen City’ then,” he said in 1971. “There were so many trees here, until the elm disease hit them and the city had to cut them down. I can still remember the trees at Wesleyan when I worked there.”

Johnson retired in 1958 and three years later began spending part of the day directing Courthouse traffic, becoming something a local legend at the busiest spot, pedestrian-wise, in the entire county.

He was a serious churchgoer, and that’s where he met his wife Elizabeth Jackson, the two marrying in 1928. “That’s where you go to get a good husband,” remarked Elizabeth. Like many local African-American women, she found work as a domestic and home laundress.

In the mid-1940s, the Johnsons purchased their first home. Joseph was 54 years old at the time, and by saving he and Elizabeth were able to make a down payment of $1,200, fully half the asking price (adjusted for inflation, $1,200 would be the equivalent of more than $17,000 today.)

They paid off the remainder in a year’s time, making monthly payments well beyond the minimum. “You’re just like an old clock,” Johnson remembered the creditor telling him, an acknowledgement of the couple’s work and savings ethic, this at a time when most African Americans faced considerable obstacles to social and economic mobility.

The Johnsons’ daughter Janice Johnson Moor taught in the Kansas City area, having earned a bachelor’s degree from Illinois State Normal University and a master’s from Kansas State University.

By 1975, arthritic knees put an end to the daily downtown excursions, though Johnson, now using a cane, remained active enough to mow his lawn every Monday and tend to a large garden. “I’ve got to get out and get these legs limbered up,” he said at the time. He didn’t head downtown much anymore, and when he did he took a city bus.

The end for Johnson came unexpectedly on March 3, 1976. It was a Wednesday afternoon when he flagged down a truck driven by John Holtz, a city water department employee, for a ride downtown. At the corner of Walnut and Elder, the 86-year-old Johnson climbed into Holtz’s cab when, without warning, he experienced some sort of attack. Holtz sped to the fire station, and from there Johnson was taken to St. Joseph’s Hospital, but it was too late. He was pronounced dead on arrival.

Upon learning the sad news, Circuit Judge Keith Campbell told a Pantagraph reporter that Johnson’s job was to make those around him feel good.

Joseph J. Johnson was laid to rest at Evergreen Memorial Cemetery in Bloomington.