Along Illinois Route 165 between the rural communities of Cooksville and Colfax in eastern McLean County is a long-abandoned, impeccably weathered farmhouse, old and forlorn but still standing strong, a testament to the craftsmanship, know-how, muscle and sweat of a century and a half past.

This lone sentinel from a lost age is a near-perfect example of an I-house, an architectural style once popular around these parts in the 19th century.

The term I-house comes from Louisiana State University cultural geographer Fred B. Kniffen, who coined the term in 1936. Kniffen noticed the prevalence of this house type in rural Indiana, Illinois and Iowa (states beginning with the letter “I,” hence “I-house”), as well as how builders from those areas carried the layout and design into Louisiana.

The I-house style goes back to 17th century England, if not earlier and elsewhere, and spread to the United States and the Southern and Middle-Atlantic regions before moving northward into states carved out of the Northwest Territory (today’s Midwest).

The I-house is considered a vernacular architectural style, seeing as it’s defined by the use of common materials and forms with little ornamentation. These homes were built through shared multigenerational knowledge carried by families and communities, and not with the benefit of commercial catalogues, pattern books or some architect’s blueprints.

Kniffen, the LSU geographer, championed the idea of folk architecture, and so emphasized the folk knowledge embedded in this vernacular yet eminently functional style of farmhouse.

Much like folktales themselves, the basic configuration of the I-house remained unchanged over time and space, though geographical variations developed as it spread to new areas. I-houses can also assume elements from a wide-range of more formal architectural styles, from Greek Revival to Queen Anne, and they were sometimes made of stone or brick, though more often than not they were wood framed.

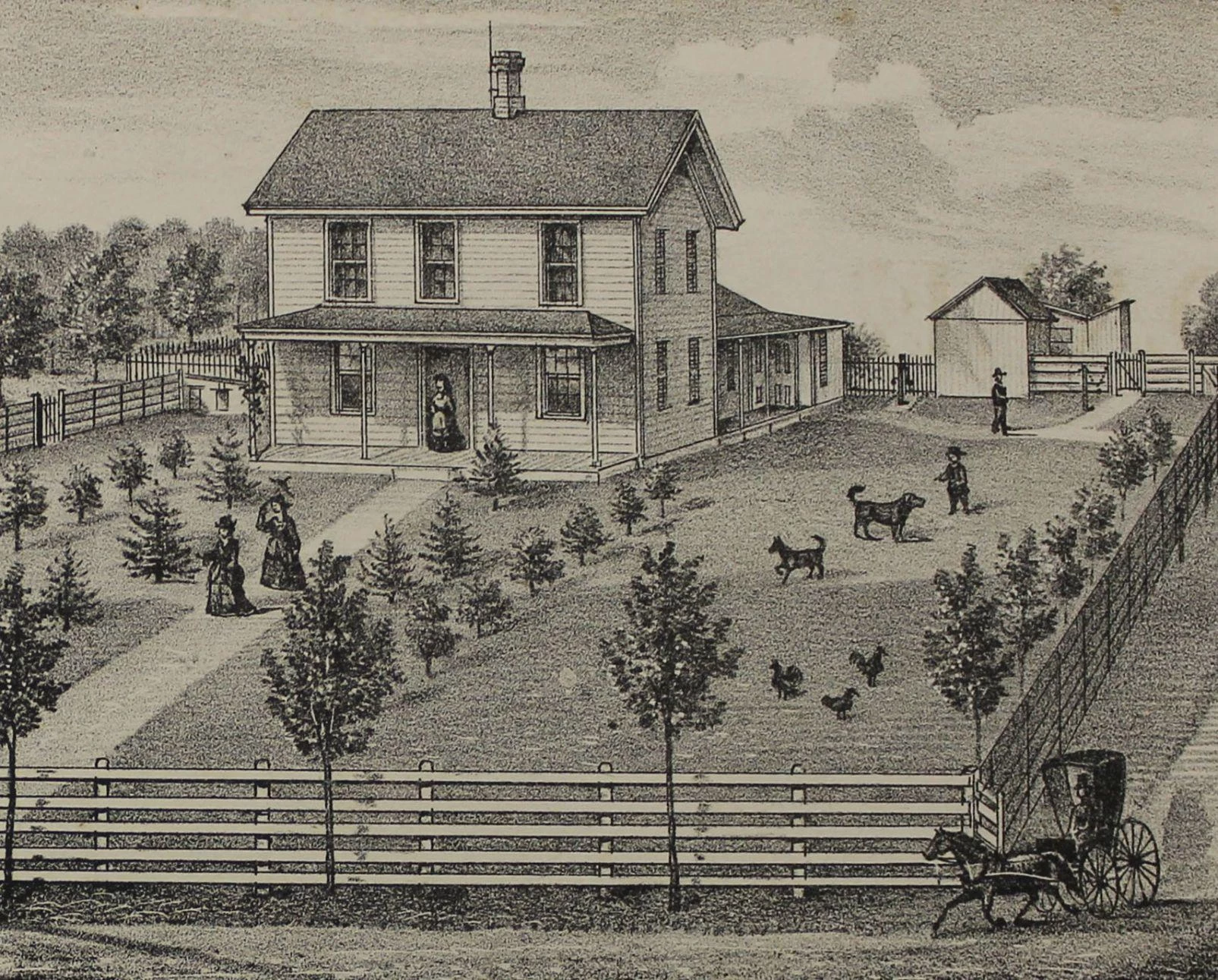

Although the I-house is a generalized form with much variation, generally speaking it features gables to the side and the easily recognizable—plain, yet aesthetically satisfying—symmetrical layout, measuring at least two rooms in length, one room deep and two stories high. The standard I-House came to have a central doorway and hallway, with three to five windows along the second story front.

The fact that I-houses were usually one room deep allowed for maximum ventilation and natural light. The chimney or chimneys were usually located at one or both of the gable ends.

McLean County was once home to hundreds of I-houses, many built by successful farmers settling here from states such as Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia, as well as the southern tiers of Illinois, Indiana and Ohio.

I-houses commonly feature one or more rear or (less frequently) side additions one or 1½ story high. These wings, or “ells,” normally housed the kitchen and perhaps a loft for hired help or children. Such additions give the rectangular footprint more of an “L” or “T” shape.

Professor Kniffen and folklorist Henry Glassie also showed how the I-house symbolized economic mobility and success on the emerging Corn Belt, a move away from the frontier world of rough-hewn logs to a more civilized one of wood framing.

This sequence is exemplified in the life and times of Isaac Funk, the Illinois “cattle king” and patriarch of a family line that would come to play an oversized role in McLean County’s development. Today, at the Funks Grove Rest Area on Interstate 55 south of Bloomington, there’s a marker at the spot where, in 1824, he erected his first permanent home—a log cabin.

Some twenty years later, Funk built an I-house at the same location as the cabin (both were lost to fire.) This I-house featured paired doors, one for each of the first floor’s two rooms, a layout that was popular at the time. “American farmers were slow to adopt the central hallway which fashionable design dictated; they seem to have regarded it as a waste of space and an impediment to ventilation,” noted Illinois State University historical geographer William D. Walters in his 1997 study of corn farming in McLean County. “By 1850, central hall and single doors had become the rule in McLean County I-houses.”

The Funk I-house is gone, but there are two others in McLean County still here and listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Hubbard House in Hudson received such recognition in 1979. The rear (or east) wing dates to 1857 and first served as the home for early town physician Silas Hubbard and his wife Juliana. In 1872, the growing Hubbard family added an I-house to face Broadway Street, Hudson’s main north-south thoroughfare. According to daughter Mary Hubbard, her mother Juliana conceived and directed the plan for the two-story addition.

A decade ago, the Hubbard House, which is a private, single-family residence, underwent extensively remodeling.

The other I-house in question, this one in the northern McLean County community of Chenoa, is open to the public. The Matthew T. Scott House, located on First Avenue a few block north of Chenoa’s old business district, was, like Hubbard’s, built in two stages. In 1855, Scott, a landowner and “prairie capitalist,” built the 1½, three-room cottage that now serves as the rear wing. He then added an attached I-house in 1863.

Interestingly, while it’s common for I-houses to include wings which were added later on, with both the Hubbard and Scott homes, the “ell” is the original part of the structure and the I-house represents the later addition.

And unlike the Funk-I house and its paired doors, both the Hubbard and Scott homes feature central doorways. The Scott I-house also carries Georgian influences, most prominently with the pediment above the second story. This handsome, historic residence earned a spot on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983. Closed for the season, the home, maintained by the Matthew T. Scott House Foundation, reopens in April.

Although the cruelties and vagaries of time, the prairie winds and humankind have depleted their ranks, there are still a good number of I-houses scattered about rural McLean County and beyond—and many in surprisingly good shape. So turn off that TV, put down the smart phone, get out into the countryside and start exploring!