World War II still loomed large over American life during the Halloween season of 1945. The surrender of Japan marking the war’s end had come on Aug. 15, a short 2 1/2 months earlier.

The magnitude of the Second World War was such that Central Illinois residents were still learning the tragic fate of loved ones who fought overseas. The Rev. William B. Weaver of North Danvers Mennonite Church, for instance, received a letter dated Oct. 17 from his daughter Emma informing him that her husband and his son-in-law, Robert Wheeler of Carlock, was killed in action on March 28 during the prelude to the U.S. invasion of Okinawa.

In the fall of 1945, the pages of The Pantagraph were also filled with one long list after another of soldiers heading back to Central Illinois and home. On Oct. 30, those discharged from Ft. Sheridan north of Chicago and Camp Grant outside of Rockford included Corp. Harry R. Allen from the Illinois Soldier’s and Sailor’s Children’s School in Normal; Mildred M. Veatch of Bloomington, a technician with the Women’s Army Corps (WAC); and S. Sgt. LaVerne Kent of Gridley.

Four days before Halloween, Illinois State Normal University held its homecoming parade, football game and dance. Facing the Redbirds on the gridiron were the Huskies of Northern Illinois State Teachers College (now NIU) in DeKalb.

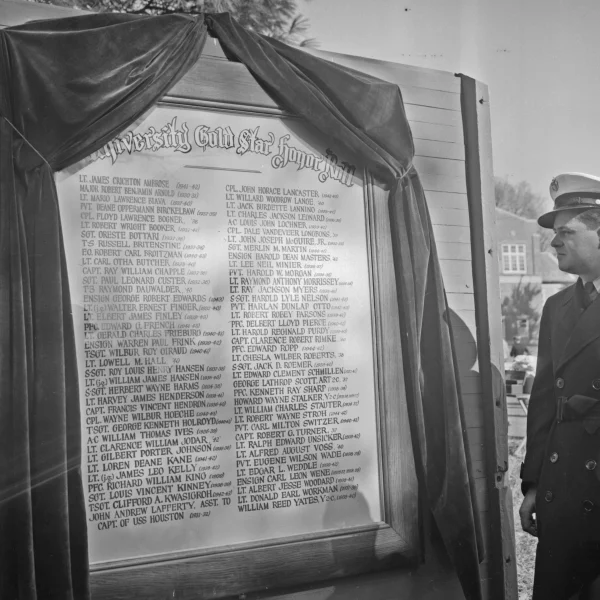

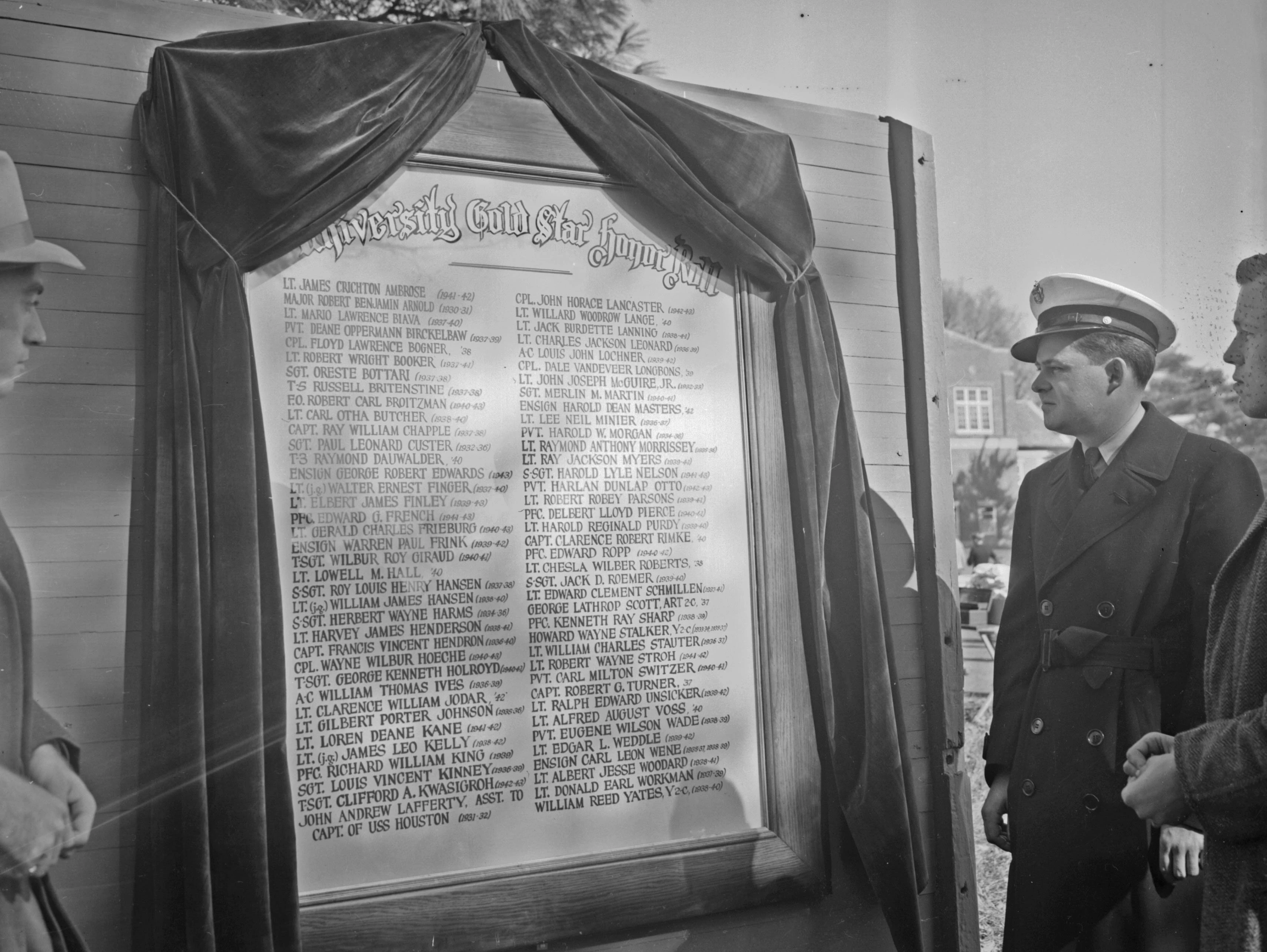

Ceremonies before the game include the unveiling of a Gold Star memorial recognizing 75 former ISNU students killed in the recently ended war (see accompanying photograph.) Also honored were some 2,500 current and former ISNU students then serving in the Armed Forces.

But not everyone’s attention was on the recently concluded war and its enormities, unfathomable losses and moral complexities. On Oct. 8, Bloomington Police Chief Clyde Hibbens “opened the annual police drive against pre-Halloween pranksters” by requesting all auxiliary officers participate in the “apprehension of youthful vandals.”

Halloween was once a far more mischievous holiday that it is today (In fact, “soap or eats!” was a common trick-or-treat greeting.) In 1945, to cite a representative example, vandals removed stop signs from city street corners, causing two traffic accidents. “These signs,” an angry Bloomington Traffic Sgt. Walter C. Lockenvitz said at the time, “are being torn down faster than we can replace them.”

Community leaders worried that the destruction of property was especially wasteful given wartime shortages and rationing still in effect. “Wanton vandalism is unusually serious this year,” read a Pantagraph editorial during the 1945 Halloween season. “Things ruined in a misguided fit of revelry are all but irreplaceable. Even soap used on screens and windows is scarce.”

“There are plenty of ways of having harmless fun,” continued the editorial.” Use your brains and energy in devising some new ones. But don’t make conditions worse during the reconversion period by careless destruction.”

The Pantagraph wasn’t going to get an argument from 2nd Ward Alderman Lawrence Turpin, that’s for sure. “For normal kids Halloween is a time for good fun,” declared Turpin, “but their good times are spoiled by a few overgrown morons who have the mentality of children and don’t know how to act.”

The end of World War II also meant the end of the unprecedented military buildup and the slow and painful return to an economy geared more toward the civilian market. By late Oct., Sears Roebuck and Co. had announced the acquisition of 80 train car loads of surplus U.S. Army ammunition boxes. “Uncle Sam doesn’t need ’em,” it was said.

These ammunition boxes were sold for 29 cents each or four for $1. The downtown Bloomington Sears was at 312 N. Center St. (the building now occupied by Fox & Hound Day Spa and other businesses.) Suggested uses for the olive-green, heavy gauge steel containers ranged from the safekeeping of valuable family papers to fishing tackle boxes.

Cities Service Oil Co. on Croxton Avenue in Bloomington sold surplus insecticide used to combat mosquito-borne disease in the Pacific Theater. The product came in 16 oz. gas-filled cylinders—“aer-o-sol bombs,” they were called—designed to release a “fog-like spray” containing 3 percent DDT. If that’s wasn’t scary enough to modern sensibilities, the insecticide—“effective against flies, mosquitoes, gnats, ants, cockroaches, bedbugs, moths, silver fish, spiders and other biting insects”—was meant for indoor use.

The federal government was also beginning to relax wartime restrictions on rationed food staples and raw materials—everything from butter to rubber tires. With regards to the former, on Nov. 1, 1945, the U.S. Department of Agriculture released 100 million pounds of butter to consumers, though it also ended subsidies and price controls that were expected to increase its cost by 5 cents a pound.

Trick-or-treating wasn’t as organized or widespread as it is today, though school-sponsored children’s parties and parades were as common then as now. In Cooksville, a small village east of Normal, the high school held its Halloween party at the community hall.

The end of World War II ushered in a massive wave of school consolidation across the Corn Belt. More than 200 one-room schools were closed for good in McLean County alone in the latter half of the 1940s. At the same time, the county’s smallest communities were losing their high schools. Cooksville, for example, closed its high school in 1949.

Back on Halloween 1945, at the state-operated Illinois Soldier’s and Sailor’s Children’s School in north Normal, kindergartners through fifth graders participated in a masquerade and played carnival games, earning points at the various booths. Treats included “doughnuts, cookies and orange drink.” Sixth, seventh and eighth graders held a party at the school’s gymnasium, entry into which required passing through a maze populated with “witches, skeletons and chicken feet.”

Meanwhile, on Bloomington’s west side, some 240 children and adults representing the Western Avenue Community Center gathered at O’Neil Park for the center’s annual Halloween party, which included a bonfire, costume parade, games and apples and candy.

But the war’s horrors could not be so easily forgotten. The military tribunals in Nuremberg, Germany seeking justice against Nazi leadership got underway less than three week weeks later, on Nov. 20.