This past week marked the 100th anniversary of the American entry into World War I, though for the other main combatants the unprecedented slaughter was nearing its third year.

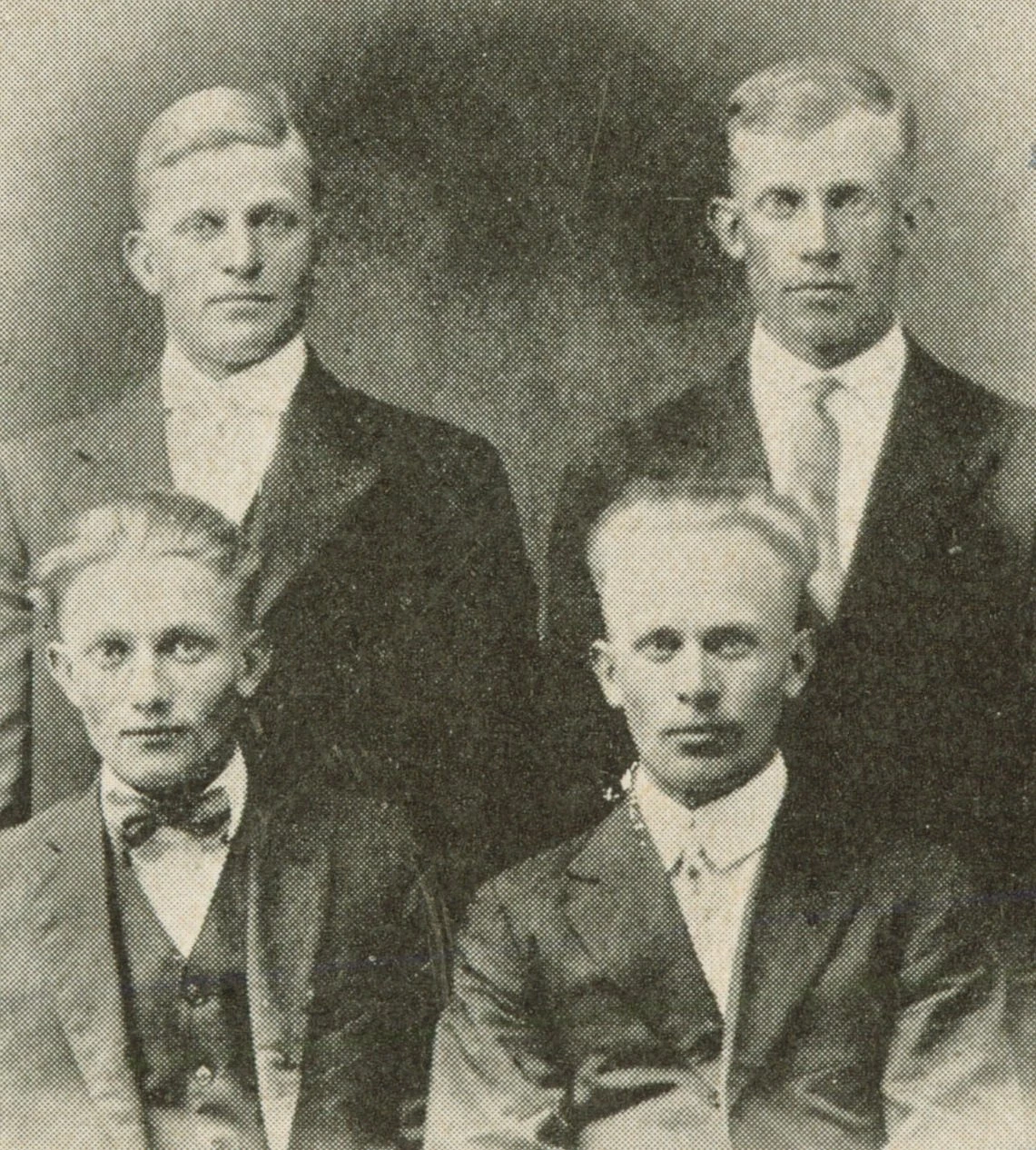

On May 7, 1917, one month and one day after the U.S. declared war on Germany, four brothers from the large Burger family entered the Bloomington recruiting station and enlisted in the U.S. Army. The four, Lloyd, age 27; Claude, 24; Ollie, 22; and Dewey, 18, were sons of Isaac and Mary (Clem) Burger. The family lived not far from the Village of McLean in southwestern McLean County.

Dewy Burger was killed in France, while Lloyd, Claude and Ollie all made it safely home.

Remarkably, there were several other families in McLean County with four sons in uniform during the war. In Bloomington there were at least four such families, including the Garbes of West Walnut Street, with sons Edward, Herman, Charles and Arthur; and the Watkins of East Chestnut Street, with sons Ferre, Warren, Paul and Harold. All eight survived the war.

Madison and Marietta Busby of Chenoa, though, had five sons in the service, which is believed the most in McLean County. Two Busby boys—Robert with the 108th Ammunition Train and Richard with the signal corps—saw their fair share of action overseas, though both survived.

Others, including Dewey Burger, were not so fortunate.

Burger had three sisters and was the youngest of eight brothers (Arch, Thomas, Isaac and Richard were the four who did not jointly enlist). Several days after signing up to fight, Dewey, Lloyd, Claude and Ollie were sent to Jefferson Barracks south of St. Louis. From there Dewey trained in El Paso, Tex. (likely Fort Bliss), and after three weeks was sent to New York City to board a troopship. He arrived in France Jun. 28, a mere month-and-a-half after his enlistment.

Burger served with Co. E, 16th Infantry, 1st Division, and was killed in action at Soissons, France, on Jul. 19, 1918, though the details of his death are few. He was buried in a nearby marked grave.

The abattoir of the Western Front churned out several hundred thousand American casualties—the dead, dying, wounded and missing—and given the resultant bureaucratic chaos, the War Department did not inform Isaac and Mary Burger of their son’s death until Aug. 10. Dewey wrote often from the front lines, and so his parents were not aware that they were receiving letters from a dead son. His final letter, dated Jul. 9, ten days before his death, arrived at the Burger home on Aug. 8, two days before they learned the awful news.

Dewey Burger was not forgotten, and today the American Legion post in McLean carries his name. In late February 1920, two-and-a-half years after the Armistice marking the war’s end, veterans from the Village of McLean and Mount Hope and Funks Grove townships began organizing an American Legion post, which would soon take the formal name of Burger-Benedict Post 573.

Ernest Benedict, the post’s other namesake, enlisted May 9, 1917, two days after the Burger brothers. Dewey and Earnest were first cousins, their mothers being sisters. Benedict was sent to France that September, and served as a corporal in the 23rd Infantry.

He too frequently wrote his parents, George and Alice (Clem) Benedict. The Pantagraph reprinted one of his letters on Jun. 17, 1918. “I have been at the front for quite awhile,” Ernest wrote. “Am sure doing my bit for Uncle Sam and all. Will not stop till it is all over, though I would like to see my loved ones. Don’t worry, mother, about me, for I will be home some sweet day.”

He was killed in early July, several weeks after the letter appeared in this newspaper, during the buildup to the Battle of Chateau-Thierry.

More than 170 servicemen from McLean County died in the “World War” (as WW I was known before WW II). Many local American Legion posts assumed the names of young men killed in action during World War I. Anchor’s post 164, for example, was named for Erwin Martensen; Bellflower’s post 202 for Earl Grant; Bloomington’s post 56 for Louis E. Davis; Colfax post 653 for Bernard Francis Davis and Albert Kerber; and LeRoy’s post 79 for Ruel Neal.

Although more than 116,000 Americans were killed in the war, that total—as horrifying as it is—pales in comparison to the losses suffered by the British and those fighting for king and country. Three English families, the Smiths, the Souls and the Beecheys, had five sons killed in the war. And a rural Australian couple, Frederick and Maggie Smith, lost six of their seven sons.

During World War II, the deaths of the five Sullivan brothers from Waterloo, Iowa, and the four Borgstrom brothers from Thatcher, Utah, led to the implementation of a Sole Survivor Policy. This Department of Defense Directive protects someone from the draft or combat duty if they’ve lost a family member to military service.

In the spring of 1921, Dewey Burger’s remains were exhumed and brought back to the states on a transatlantic steamer. He was one of tens of thousands of American dead returned home in the years after the war. On May 19, he was laid to rest one final time at McLean Cemetery, which is located west of the Village of McLean.

Two months later, Ernest Benedict’s remains likewise returned home, and on Jul. 24, he too was reinterred at McLean Cemetery. Benedict’s pallbearers included Lloyd, Claude and Ollie Burger.

According to the official history of McLean County in World War I, the Dec. 1, 1917, opening of the Mount Hope Township Hall in downtown McLean presented one of the most memorable scenes of the entire home front effort.

The highpoint of the civic gathering was the presentation of service flags by the Rev. Edgar D. Jones of First Christian Church, Bloomington. Local families received a flag if they had someone serving in the military, with the number of stars on the flag representing the number of family members in uniform.

“During the presentation eyes of men and women all over the house brimmed with tears, and sobs were even audible,” reported The Pantagraph. “When flags bearing two stars and then three stars were shown the applause grew in volume, and when Rev. Mr. Jones silently held up one bearing four stars [for the Burgers] the crowd was divided into those who cheered and those who wept.”