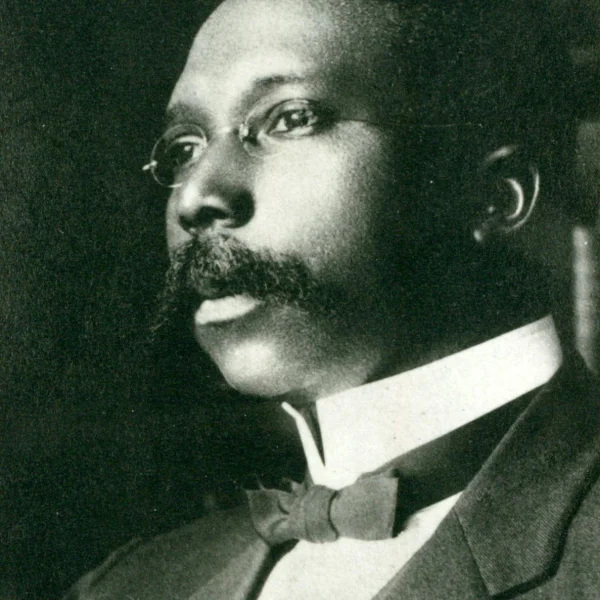

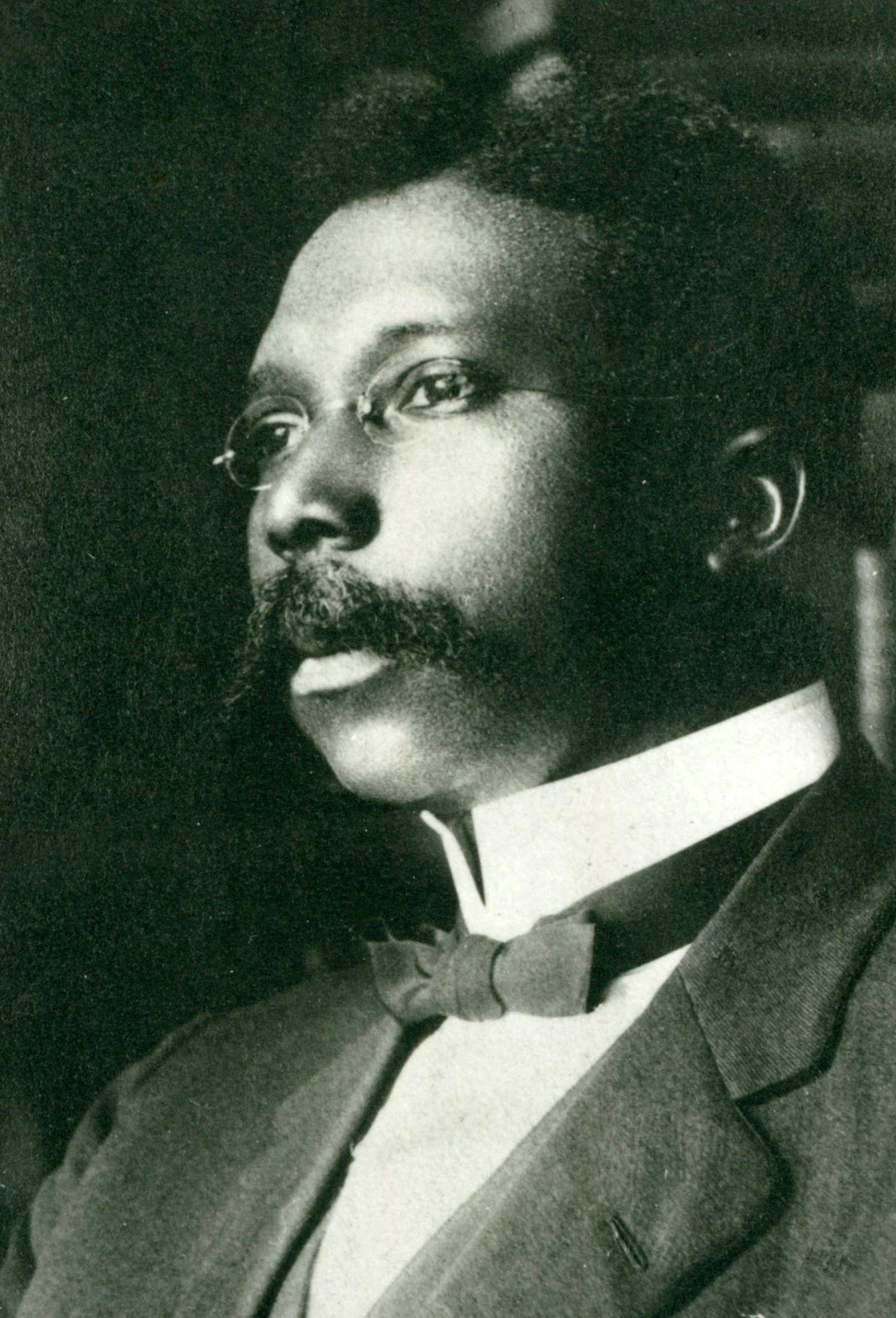

African-American physician Eugene G. Covington came to Bloomington about 1900 to open a medical practice.

This being thirty-five years after the end of the Civil War, one would think things were getting better for African Americans, at least in the North. Unfortunately that was not the case in Bloomington-Normal where black residents faced increased segregation and discrimination.

By the 1890s, to cite several representative examples, African Americans could not stay at Bloomington hotels, and if they wanted to attend a local theater they had to sit in the back rows. And in 1908, Bloomington park commissioners decided to establish segregated beaches and changing rooms at Miller Park.

The Springfield Race Riot of 1908 and a far bloodier “race war” in Chicago during the summer of 1919 cast a further pallor over any attempts to halt deteriorating race relations in Bloomington-Normal.

In the early 1920s a resurgent Ku Klux Klan and its call for “pure Americanism” and white supremacy enjoyed wide support in McLean County. There were Klan parades in downtown Bloomington and rallies along Jersey Avenue. And by the 1920s downtown Bloomington restaurants began refusing service to African Americans.

In addition to these humiliating and petty (and decidedly un-American!) discrimination and segregation practices, African Americans were barred from most professional employment opportunities. For example, black students could attend Illinois State Normal University and earn teaching degrees and certificates, but local public schools declined to hire them.

Given this pervasive environment of fear and hate (how else should one describe it?), it’s not surprising that Covington was the only African-American doctor to work in McLean County until the 1930s.

Born on Aug. 1, 1872, in Rappahannock County, Virginia, to former slave parents, Covington exhibited a sharp intellect from an early age. He eventually graduated from Howard University, a historically black school in the nation’s capital.

In 1902, two years after Covington arrived in Bloomington, he married Alice Alena Lewis from the upstate New York community of Oswego. They eventually settled into a cozy residence at 410 E. Market St. and raised a family, with three boys surviving into adulthood.

Covington expressed his frustration with the increasingly ugly racial climate in Bloomington-Normal with a lengthy guest column in the March 7, 1903, Pantagraph. In this essay, titled “The Race Question,” he took the opportunity to criticize a local member of the board of education for demanding that African Americans “do something to warrant and inspire respect.” Covington found such complaints disingenuous, given the pervasive discrimination faced by blacks. “We are told not to apply for positions as teachers,” he said by way of example. “And yet the gentleman says we must do something to merit respect.”

In fact, Covington was acutely aware of the issue of respect, or rather the lack thereof. Both Eugene and Alice refused to attend the theater in Bloomington-Normal due to the humiliation of segregated seating arrangements.

Although he earned a reputation for his civil rights advocacy, Covington was first and foremost a respected physician and surgeon. In addition to his family practice he was a member of the St. Joseph’s Hospital staff and had full privileges at Mennonite Hospital.

St. Joseph’s admission records show that Covington treated mostly black patients for everything from “nervous prostration” to influenza. As a rule, a white physician had to be in attendance when Covington performed surgeries. Yet on occasion it appears as if Covington was the only physician in the operating room, as was the case in late February 1913 when he performed a successful appendectomy on a 23-year-old African-American.

In February 1908, Covington complained to the McLean County Medical Society that some white doctors were undercharging African-American patients who could afford to pay the full standard rate of $2 for house calls. Covington said such undercutting put an undue burden on his practice, since the majority of his patients were black. The society agreed with Covington, calling undercharging “an infraction of professional honor.”

During Covington’s lifetime African Americans were closely aligned with the Republican Party, given a legacy that included Abraham Lincoln, emancipation and the defense (at least until 1877) of political and civil rights for freed people in the post-Civil War Reconstruction Era. For most African Americans the switch to the Democratic Party came during the Great Depression and Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency.

Back in the summer of 1908, Covington played a leading role organizing a parade and rally for Republican Richard Yates, Jr. and his bid for the party’s gubernatorial nomination. “A good-sized audience was present to hear the colored speakers,” reported The Pantagraph, “and not a few of the white voters of the city were in attendance.”

Although the local Republican Party welcomed African-American support at the ballot box, by the early 20th century there was little interest in political and civil rights. Not only was the “Party of Lincoln” increasingly disinterested in racial equality, but loyal black Republicans faced discrimination within the party itself. Covington, for instance, was on the local Republican Party central committee in 1909, though he and two other African Americans were not allowed to sit on a regular ward committee but were relegated to an at-large (and all-black) committee.

In early 1915, Covington was one of nearly 50 candidates who ran for four open city commissioner seats. His campaign slogan, “With malice towards none, goodwill to all,” was a nod to Lincoln’s second inaugural address. Covington was not one of the top four vote getters, but he did finish with a respectable middle-of-the-pack showing.

Alice Covington passed away in 1925, and three years later Eugene married Amanda Thomas, a widow and longtime friend of the family. The marriage wasn’t a long one because Eugene died on February 3, 1929, after a short illness. He was only 56 years old and still practicing medicine.

Eight years earlier, in May 1921, Covington participated in one of the periodic debates held by a group of local African-American pastors. The topic, “Resolved that the Negro should stay in the South for better advantages,” featured Covington arguing in the negative.

For African Americans in the early 20th century, Central Illinois certainly offered brighter opportunities—socially, politically and economically—than the Deep South. That said, segregation of downtown Bloomington hotels, restaurants and theaters, as well as Miller Park beaches, continued into the 1960s. And major Twin City employers didn’t begin to hire black professionals until the late 1960s.