1994

Who had the power to control another human's body?Current and Former Employees

Twenty-nine current and former female employees of DSM (renamed Mitsubishi Motor Manufacturing of America [MMMA] in June 1995), represented by Peoria attorney Patricia Benassi, charged the automaker with sexual and racial harassment and discrimination.

More than a year after the suit was filed, on April 8, 1996 the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) also brought suit against MMMA. The EEOC alleged that hundreds of employees had been sexually harassed since 1990 and that the automaker “took no effective steps to prevent or correct it.”

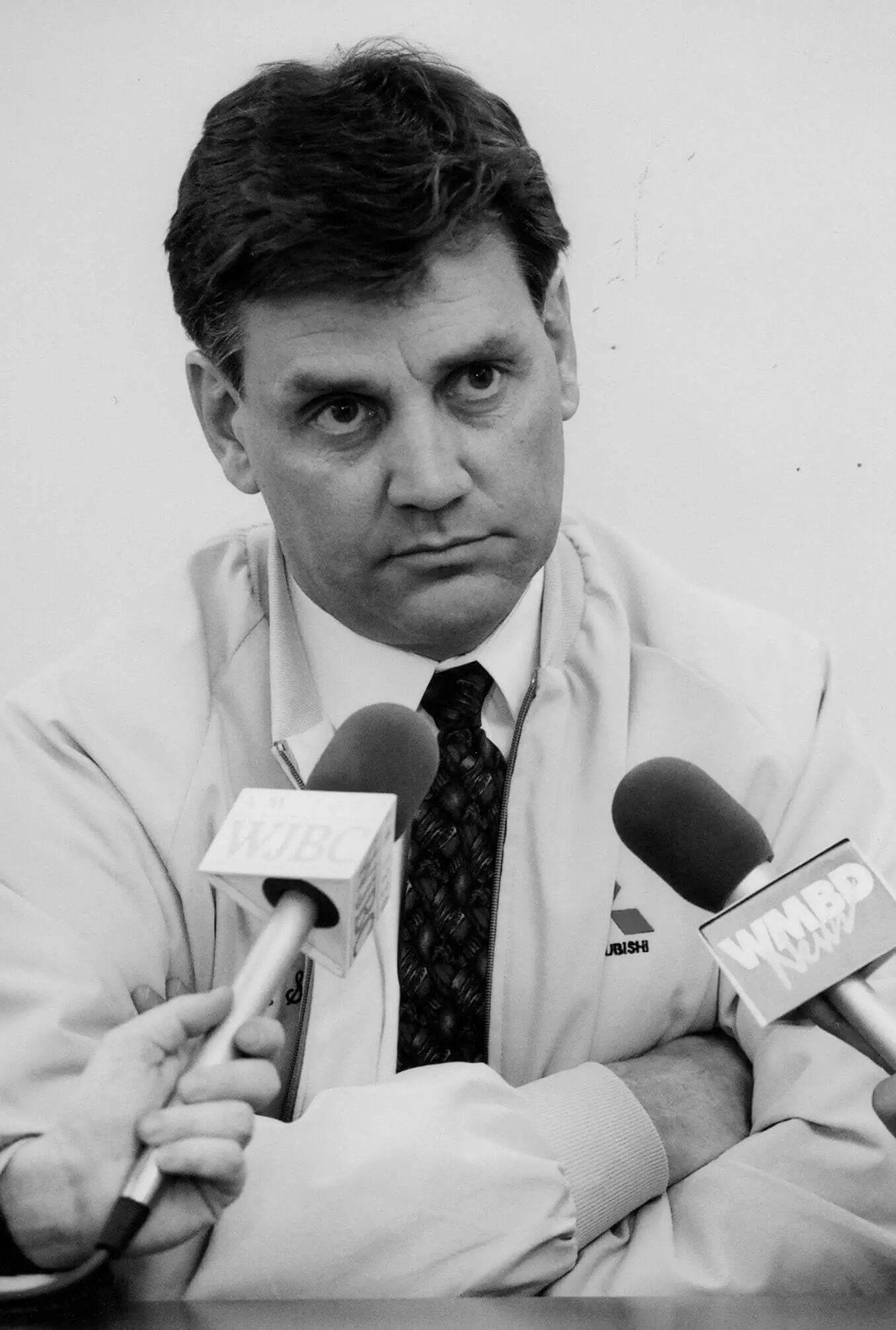

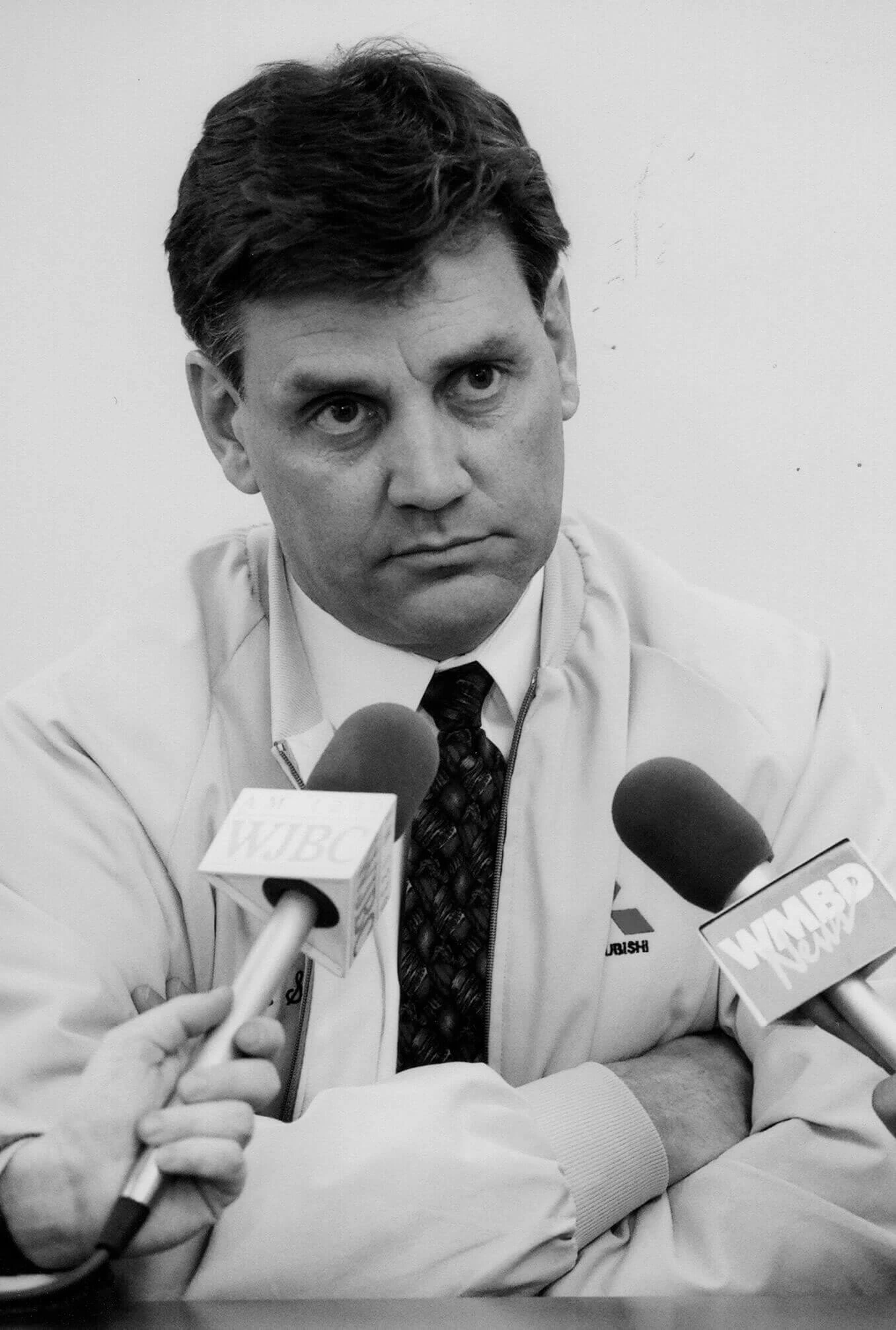

Plant Managers

MMMA plant management and attorney Gary Schultz vehemently denied the claims.

Union leaders believed that all former claims of sexual harassment and discrimination had been satisfactorily resolved.

Workers at the plant — most members of the United Auto Worker (UAW) local 22488 — had mixed feelings regarding the lawsuits. Some did not believe the allegations; some were skeptical; many just wanted to get past the lawsuit and do their jobs; and others wanted to know exactly what happened and were hopeful the suit would go to trial.

Who had the power?

MMMA Denies the Charges

As the lawsuit proceeded, MMMA management and company leaders denied the charges. News coverage was limited at first. But when the EEOC filed a lawsuit in April 1996, coverage increased dramatically.

“The Twin City Company has engaged in a pattern and practice of discrimination against a class of female employees by subjecting them to sexual harassment and sex-based harassment, retaliation and a work environment so intolerable that it forced some of them to quit.”

— EEOC Press Release

April 1996

Listen to an audio clip of this story...

Evidence gathered by reporters for the Washington Post uncovered disturbing information.

Union official Charles Kearney acknowledged that complaints were handled off the record to avoid formal complaints and that no records were kept. He later denied these statements. Multiple women stated that their informal complaints received no action and that they were forced to continue working with the individual(s) who harassed them.

One formal complaint, handled by the union's bargaining committee, resulted in an intercom announcement of the complain and further harassment made by male coworkers of the woman who made the complaint.

On Friday, April 12 an employee meeting was called by plant managers.

Led by Gary Schultz, its purpose he said was “to respond to workers . . . who were supportive of the plant and wondered if they could do anything.”

Reports of the meeting varied widely, including the report made by the plaintiffs' attorney Patricia Benassi, who was not at the meeting.

Benassi’s account (given to the Bloomington Pantagraph) claimed Schultz made the following statements or suggestions:

If employees don’t stick together, car sales would drop and everyone could lose their jobs.

Employees were told to begin circulating petitions stating the women alleging harassment are not telling the truth and that sexual harassment does not exist at MMMA.

Employees were urged to contact the media and their congressmen, and were told telephones were being installed for them to use.

Employees were urged to attack the plaintiffs.

When asked whether the women’s allegations in the private suit were true, Schultz “assured” the employees the company would win if the case goes to court.

Schultz responded to Benassi’s claims, making the following statements to the Bloomington Pantagraph:

“If sales go down, it could affect our employment security.”

“The idea for petitions and in-plant telephones came from employees at the meeting. Many of the activities were underway before the meeting.

Employees were urged to join the employees who had come up with the ideas.”

“Of course I didn’t [urge employees to attack the plaintiffs]. The Friday meeting was about the EEOC lawsuit, not the private one filed in 1994.”

When asked whether the women’s allegations in the private suit were true, Schultz responded, “The company will be able to answer every charge filed by the women.”

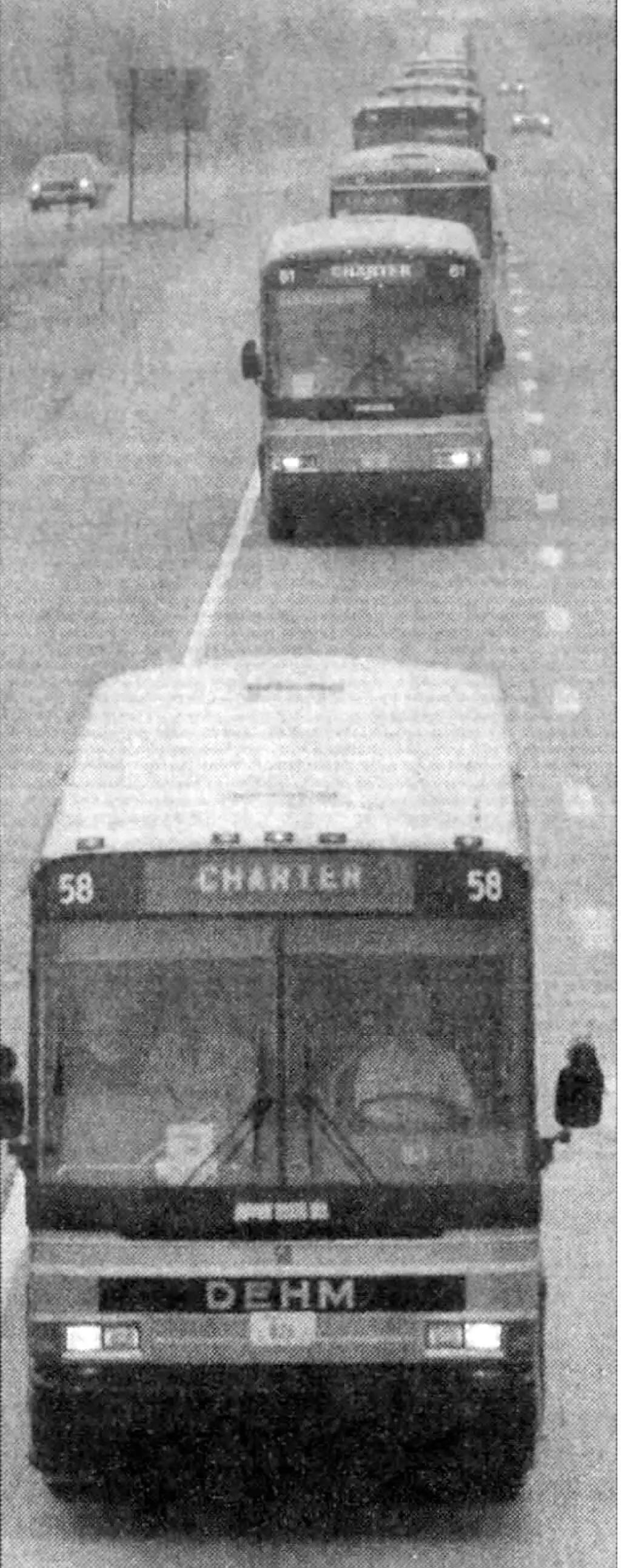

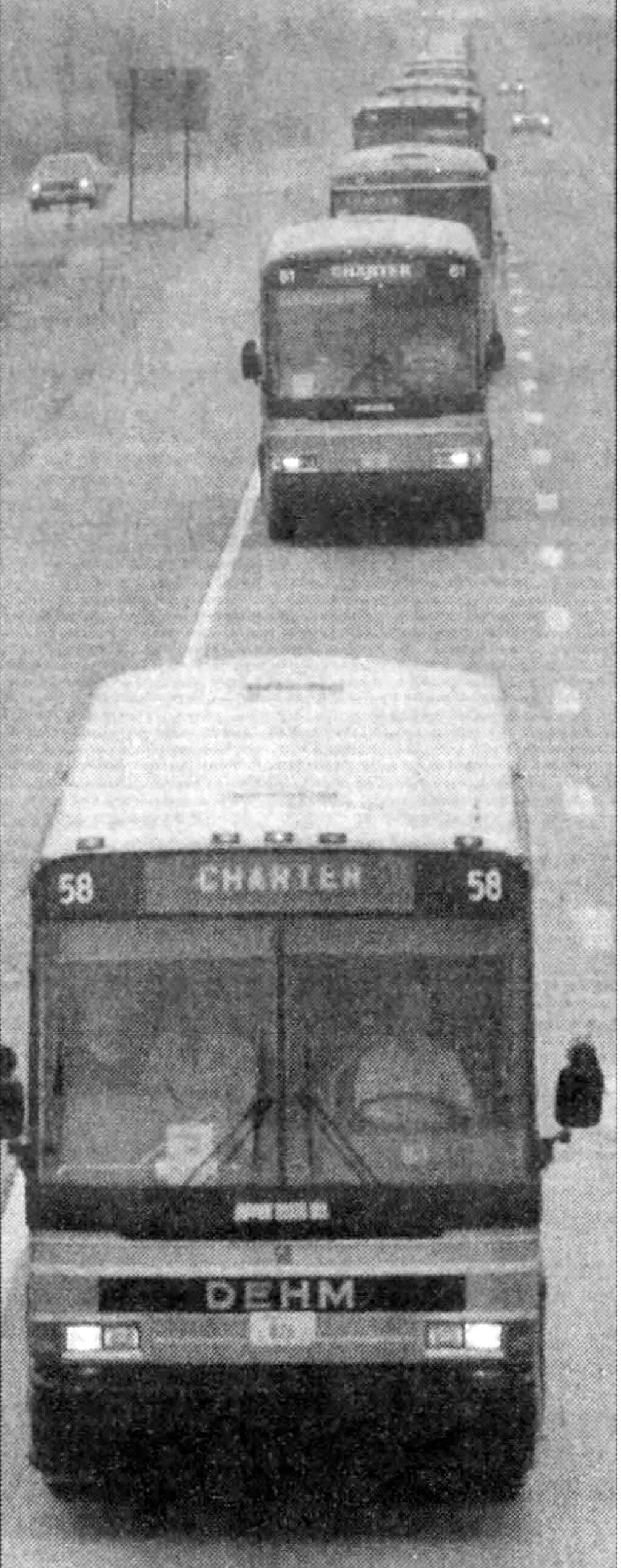

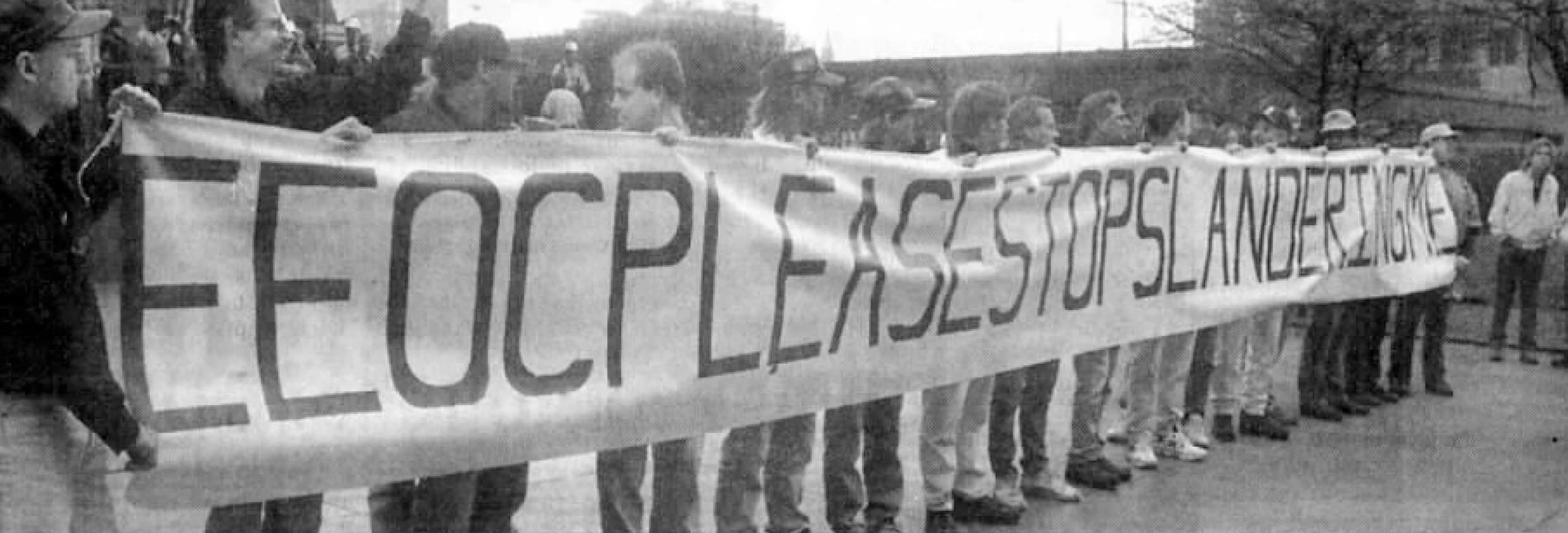

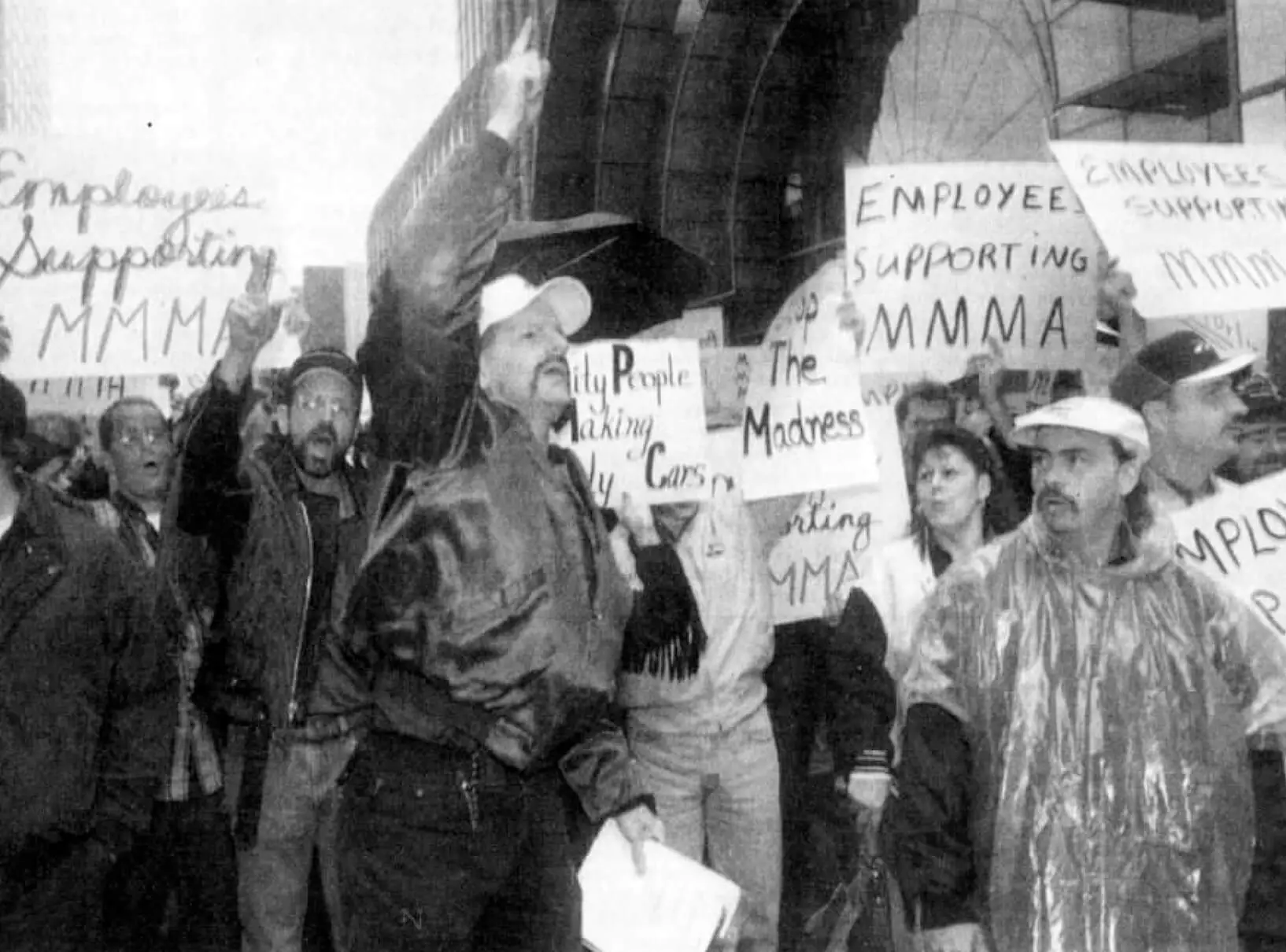

On Monday, April 22, about 2,900 Mitsubishi employees boarded 59 buses and traveled to Chicago where they demonstrated in front of the EEOC offices in support of their employer.

MMMA paid for the bus transportation, provided a boxed lunch, and gave participants a paid day off. Employees who chose not to go, did not get the day off. Instead they spent the day doing clean up at the plant.

UAW President Stephen Yokich, criticized Mitsubishi for the company supported trip to Chicago.

“Mitsubishi's efforts to pressure its employees into demonstrating against the EEOC's efforts to provide all of Mitsubishi's work force with a work environment free of sexual harassment is just plain wrong. Instead of opposing the EEOC, Mitsubishi would do better to work with the agency and the union to redress past wrongs and make whatever changes are necessary to ensure that its work force is protected from any kind of discrimination, now and in the future.”

— UAW President Stephen Yokich

“We're here because we do not agree with the allegations of the EEOC. I absolutely don't want to be part of a class-action suit.”

— Rochelle Fry

“The EEOC brought the whole company into this when only a few women are involved. The people are here because we're not involved. We think the EEOC should do it one-by-one.”

— James Bond

With growing concerns about the negative publicity, MMMA’s top executive Tsuneo Ohinouye announced on April 25, 1996 that he wanted to settle the lawsuit.

During his announcement Ohinouye finally admitted that sexual harassment had occurred at the Mitsubishi plant. He also reported that the company had handled 89 cases since the plant began operations in 1987, and that 10 employees had been fired as a result, including four since the beginning of the year.

The following month Ohinouye announced that Mitsubishi had hired former Secretary of Labor Lynn Martin to review and update their sexual harassment policies.

The action garnered positive feedback from the community and employees, as well as from the media.

On August 28, 1997, MMMA agreed to pay $9.5 million to the 27 plaintiffs represented by Benassi in the 1994 lawsuuit.

In June 1998 MMMA settled with the EEOC, agreeing to pay $34 million to the plaintiffs in their case.

The settlements both included silence clauses with the plaintiffs. As a result many of the details of the harassment were never revealed to the public.

Reflection Questions

Who had the power to control the effects of Mitsubishi’s harassment policy?

Why was the case settled outside of court instead?

Who benefitted most from a settlement?

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County