1931

Who had the power to be heard?Bloomington's Civic Relief Committee

Members of Bloomington’s Civic Relief Committee established a relief office in 1930 to provide assistance to the unemployed. They were community volunteers who gathered and made donations of food and clothing, and later distributed state and federally supplied funds in the most “economically and efficient manner in order to conserve supplies while still providing the necessities for survival.” Members tried to do this in a transparent manner.

Bloomington's Unemployed Council

Members of the Communist Party of Illinois saw the Depression as their opportunity to encourage change and overthrow the pervading capitalist system. Some formed Unemployed Councils as a conduit for such efforts. In 1932 Henry “Hank” Mayer became the driving force of Bloomington’s Unemployed Council. But not all of those who joined the council were communists — some joined just hoping to improve their situations.

Who had the power?

Listen to an audio clip of this story...

Bloomington's Unemployed Council

On January 8, 1932 members of Bloomington’s Unemployed Council held a rally at Bloomington’s Coliseum where they proposed a series of relief measures to the 1,000 persons in attendance.

The Council Had Eight Demands

The Council had demanded increased relief the previous June, but to no avail. Now they had eight specific demands:

Winter relief of $150 (equal to $8,300 in wages in 2017) to each unemployed worker, plus $50 for each dependent

Public Works jobs paid at union wages, and free distribution of surplus cotton and grains to the unemployed

Free rent, gas, light, water, etc. to all unemployed workers, reduced rates and rents for part-time workers

Six-hour workdays with no reduction in wages, and a five-day work week

Payment of full wages to all part-time and stagger plan workers by the employers

Prohibition of forced labor or coercion of any kind in connection with insurance or relief for the unemployed and no discrimination against colored and foreign-born as to jobs, relief, insurance, or in any other form

Full and immediate payment of the balance of the bonus

On January 23 a group of 25 men of the Unemployed Council, led by William J. Hall, marched to city hall. They repeated these demands to Bloomington Mayor Ben S. Rhodes.

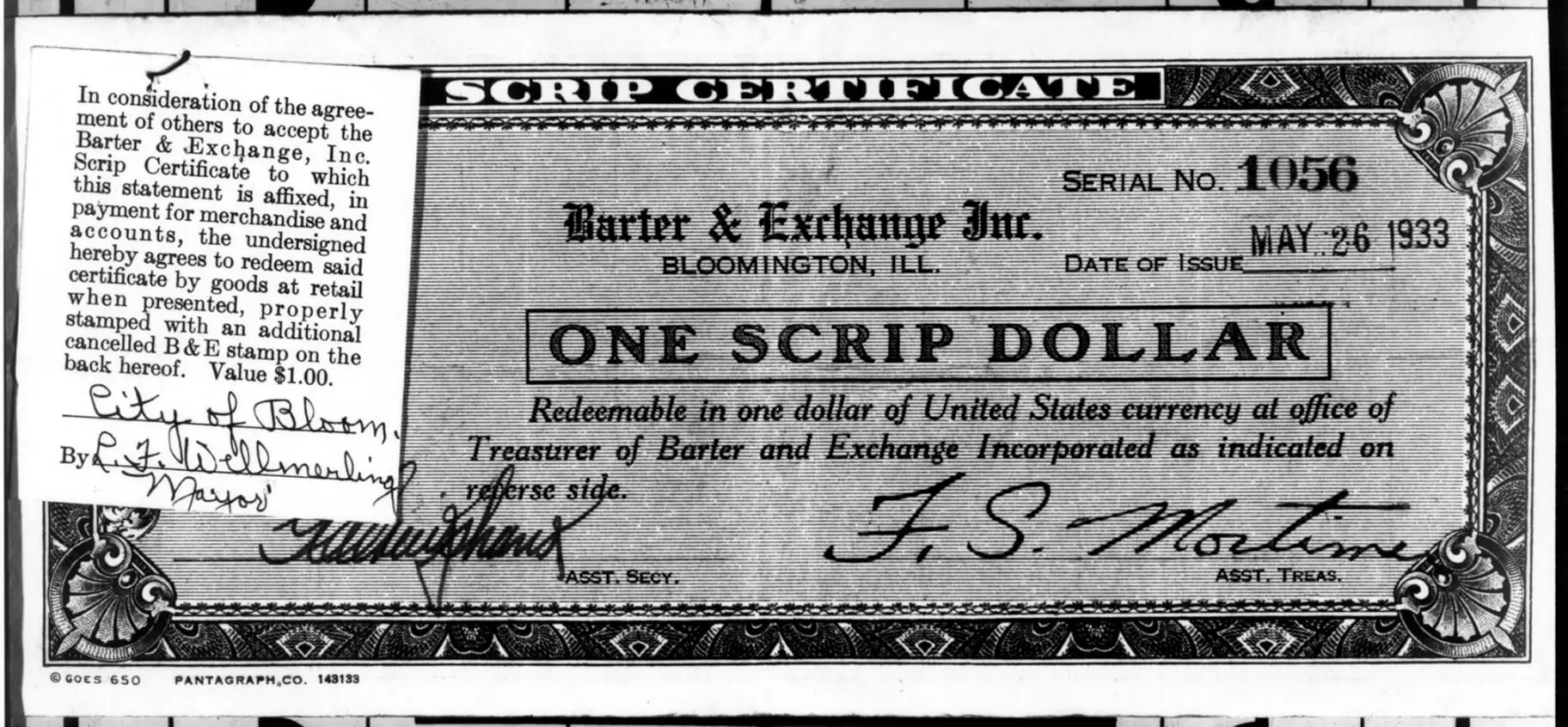

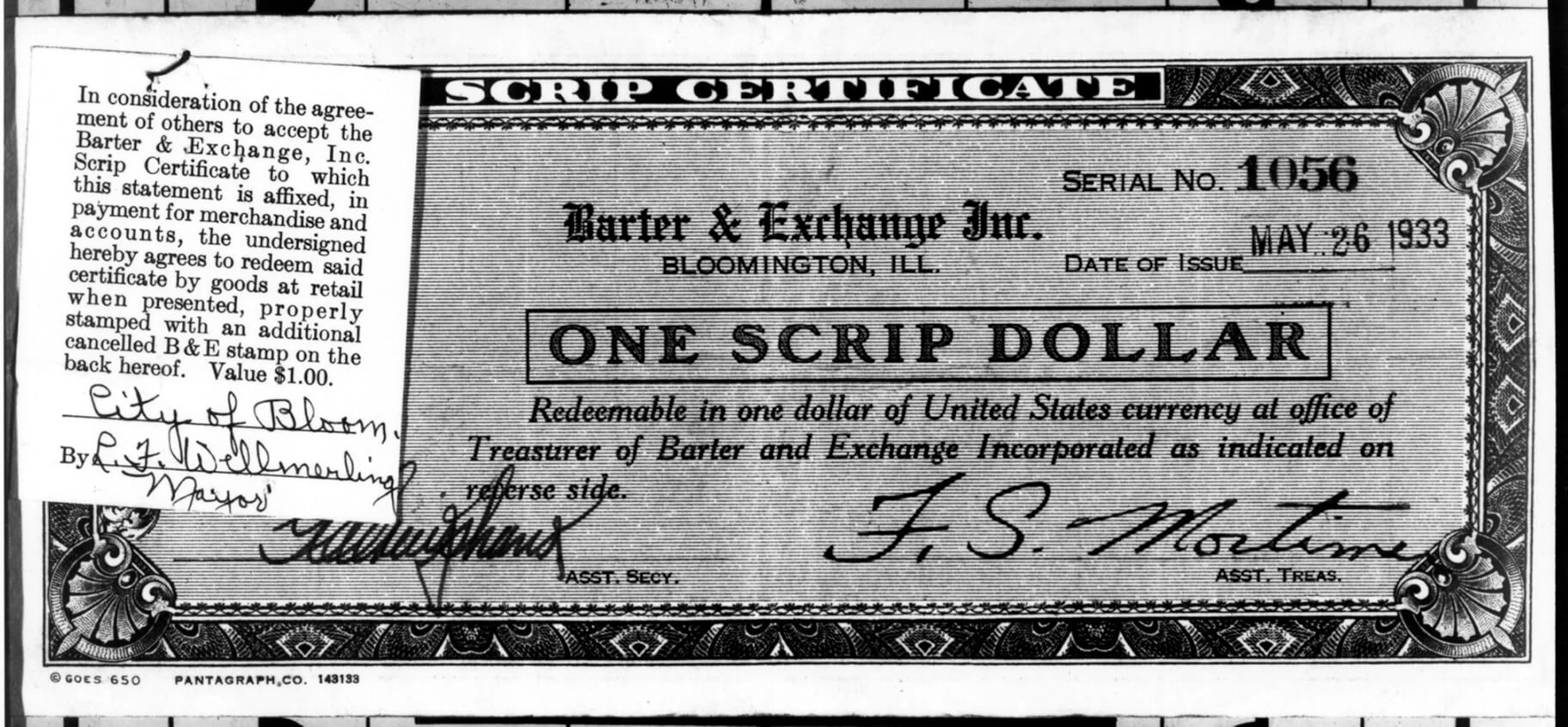

One scrip dollar, circa 1933

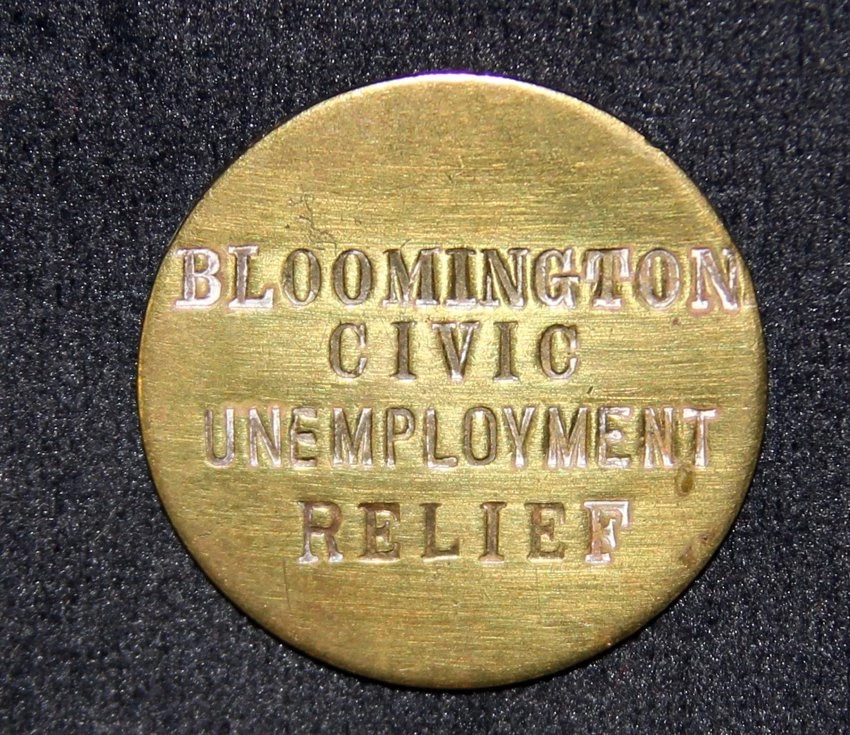

Bloomington’s Civic Relief Office distributed brass tokens and paper scrip that could be used like cash to purchase certain items in local stores. But members of Bloomington’s Unemployed Council objected to the use of scrip because it limited what could be purchased with relief funds.

Demanding Change

The Unemployed Council regularly besieged Bloomington’s relief office and its workers with demands for free water, light, and gas.

They also gathered (sometimes without permits) to hold parades and rallies demanding change, including the replacement of relief office workers who refused to accept their demands.

A Mass Meeting

On June 11, 1933 the Council tried to gather on the Main Street side of the courthouse square. But as they had no permit, sheriff deputies ordered them to leave. After several attempts to disperse the crowd, deputies broke up the mass meeting using tear gas.

When the air cleared, the crowed returned with handbills printed with “Demand the Right of Free Speech.” The rally proceeded, closely watched by Sheriff Reeder and his deputies.

Unemployed Council member George W. Clark spoke condemning capitalism as a . . .

“Rotten system... The bosses are clamping down the screws, and forcing officers of the law to discourage mass meetings of the workers.”

— George W. Clark

He then threatened:

“Things will get much worse unless the unemployed are allowed to meet and plan a method of changing the government.”

— George W. Clark

"Suspicious" Intentions

In March 1933 members of the Unemployed Council suggested the intentions of the Civic Relief Committee were “suspicious” (asked for too much personal information) when a new questionnaire began to be used for those applying for relief.

On Friday, March 31, the Civic Relief office manager, Ned Dolan, stepped onto a box outside of the office and made the following statement to the picketers:

“I see but one way to settle this misunderstanding—we will go the whole way with you. Each of you may be the judge of how much you desire to tell upon the questionnaire...We cannot allow our misunderstanding to continue. It is not fair to allow our children to go hungry because we cannot get together on these points. Therefore we are going the whole way with you. Our hope is that you show a desire to be fair, even as we are trying to be fair.”

— Ned Dolan

Unemployed Council picketer Roy Whittinghill took the stand immediately after Mr. Dolan.

“We know that there are many getting relief who do not deserve it. Personally I can see no fault in what Mr. Dolan has said. And for myself, I am going to give the committee all the information it is seeking.”

— Roy Whittinghill

A New Set of Demands

Less than a month after the Civic Relief office conceded enforcement of the application questionnaire, the Unemployed Council announced a new set of demands, distributed new handbills, and planned additional demonstrations.

But the Civic Relief Committee had no intention of giving in to their demands. They were well aware that an exhaustion of funds and supplies was exactly what the group’s leader, Hank Mayer, wanted. Mayer was planning an uprising of the unemployed and boasted that he would be the guiding spirit in his prophesied “new order” that would be effected by the “revolution” he also predicted.

In May 1934 the Bloomington Trades and Labor assembly proposed that Bloomington and McLean County “take steps to disrupt the Unemployed Council.”

Soon after that Mayer left town, and the organization dissolved.

“This organization, from time to time, in their meetings and other places, passed remarks in opposition to the American Federation of Labor, and...has caused no little trouble in Bloomington by attempting to incite riot.”

— Bloomington Trades and Labor Leadership

1934

Reflection Questions

Why did the Unemployed Council take issue with how relief was distributed?

Did they truly think it was unfair, or was there an underlying agenda?

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County