1970

Who had the power to gain respect?White Administrators

White administrators, teachers, and students at Bloomington High School believed discrimination was under control.

Black Students

Black students at Bloomington High School felt there was little understanding of their culture. Many had stories of discriminatory treatment there. African American teachers at the school, as well as students' parents, feared retaliation if they spoke up.

Who had the power?

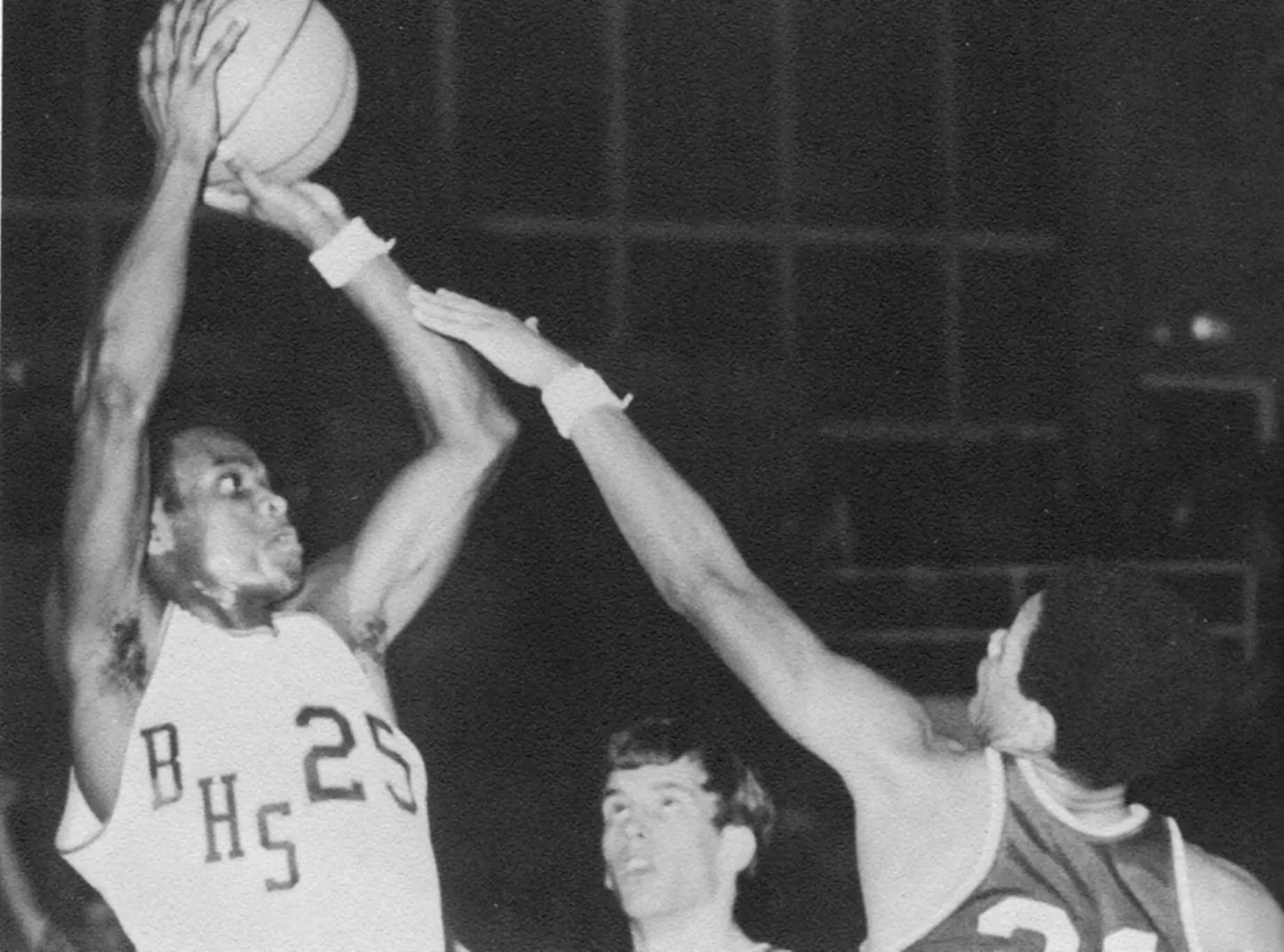

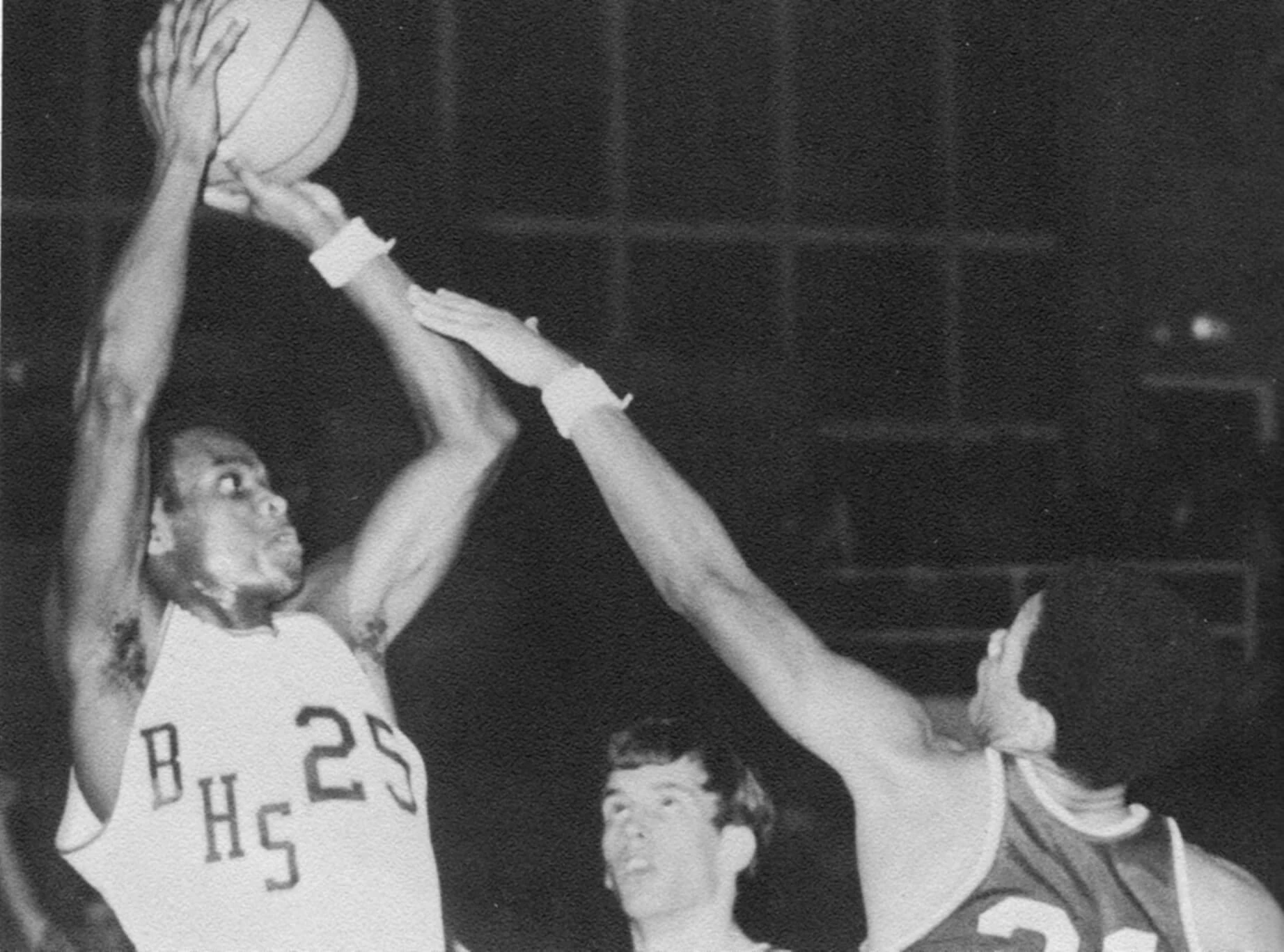

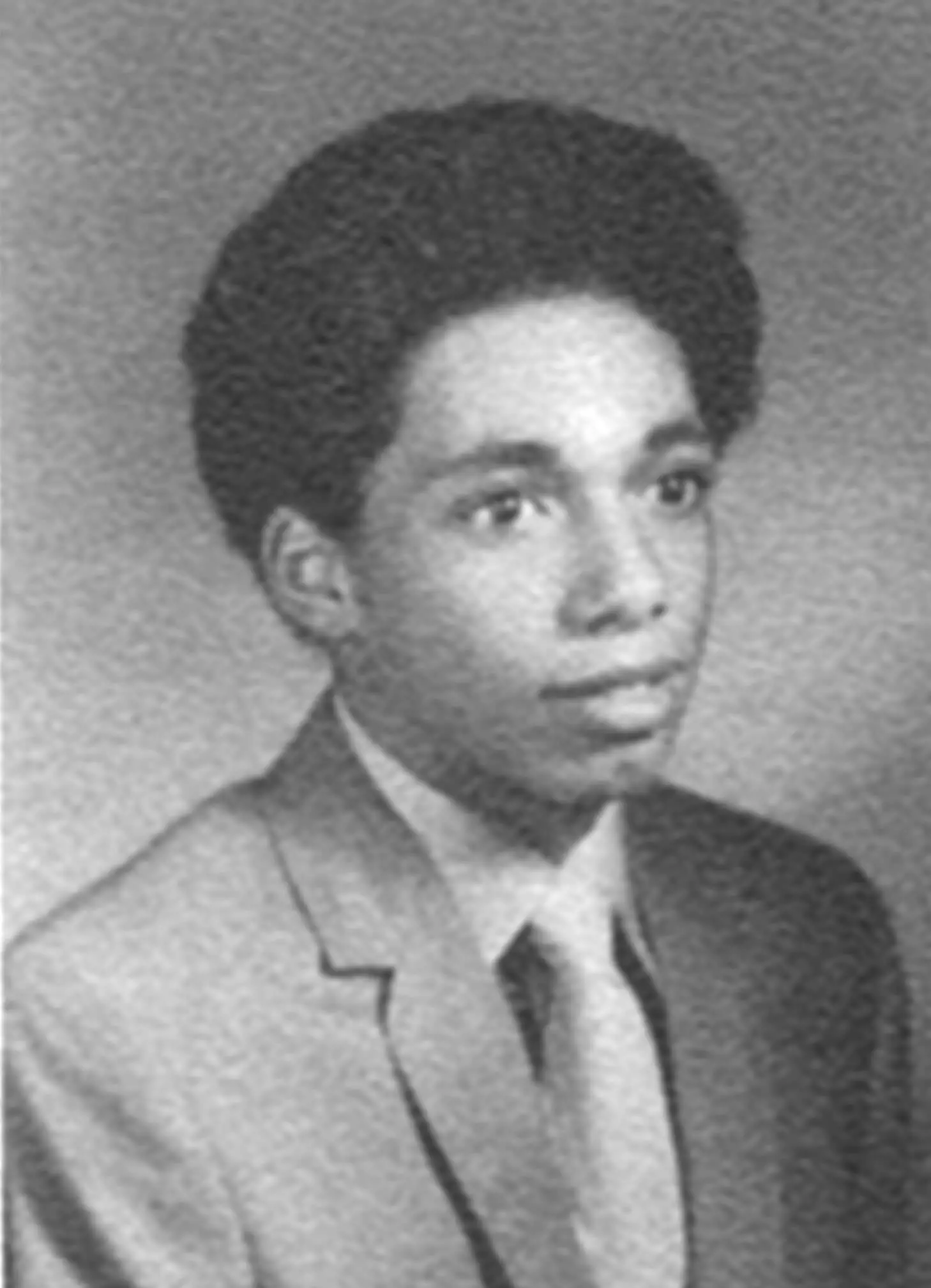

Reggie Curry

In early February 1970, Bloomington High School (BHS) basketball star Reggie Curry was pulled to the side by his basketball coach Ralph Sackett and told, “Quit the Afro-American Club and cut your hair, or I’ll cut you from the team.”

Curry was angry. He knew this was wrong and reported the incident to his school counselor, James W. Lyle, who then reported it to the principal.

Curry also told his friends about the incident. Many of them shared their own experiences of discrimination.

The Afro-American Culture Club was an all-African American student group that met “to develop a better understanding and appreciation of Afro-American Heritage.” James Lyle, the only Black counselor at the school, was the club’s school advisor and worked with them to ensure they followed school policy.

When Principal Elwood Wheeler asked coach Sackett about the incident, Sackett confirmed that he had indeed made the demands.

There were no consequences for coach Sackett’s demands on Curry. But Lyle, who tried his best to counsel students who asked for his help, was let go at the end of the school year.

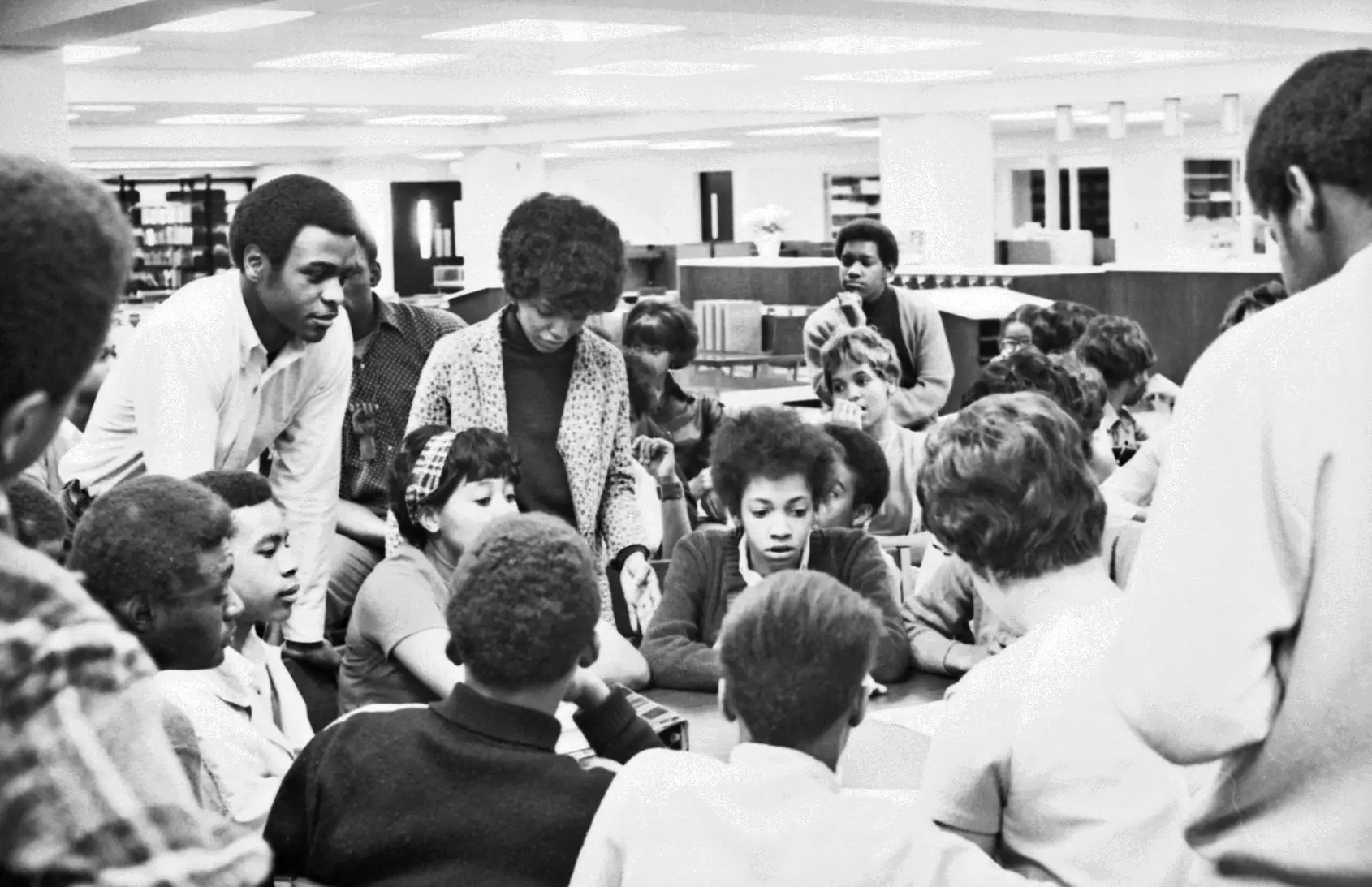

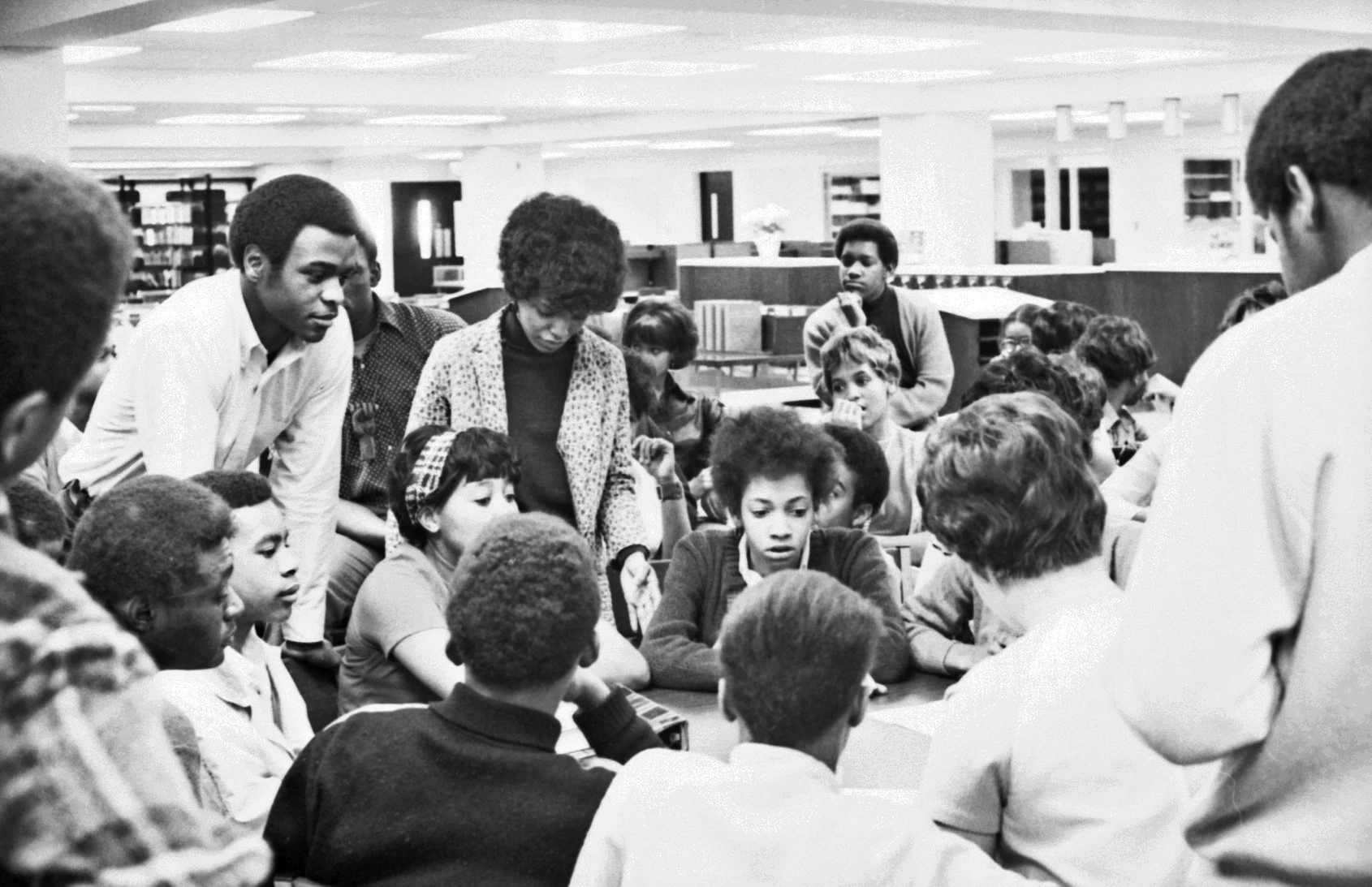

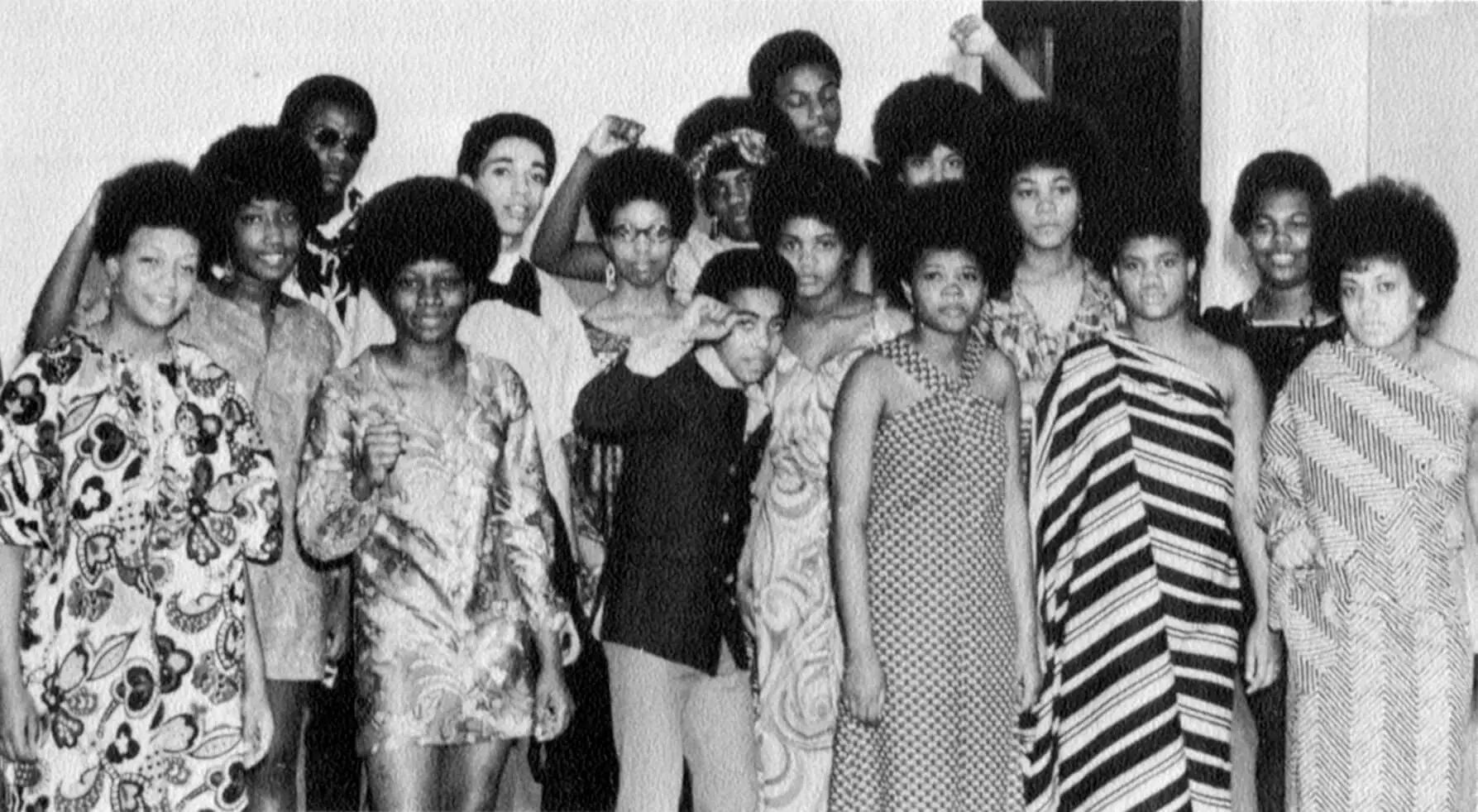

Members of the Afro-American Culture Club, left to right: Pat Morris, Nita K. Collins, Reggie Curry, Carrie Beverly, Mike Jones, Willa Thomas, Marvin Thompson, Joyce Curry, Sandol Jones, Steven Jones, Joyce Ann Thomas, Dorothy Phifer, Beverly Ray Pendleton, Donna Thornton, Sandy Tucker, Alice Kay Thornton.

Students Boycott Classes

Disturbed by the number of incidents of discrimination and frustrated by the lack of respect and understanding for their culture, a group of students, many of them members of the Afro-American Culture Club, decided to boycott classes on February 26.

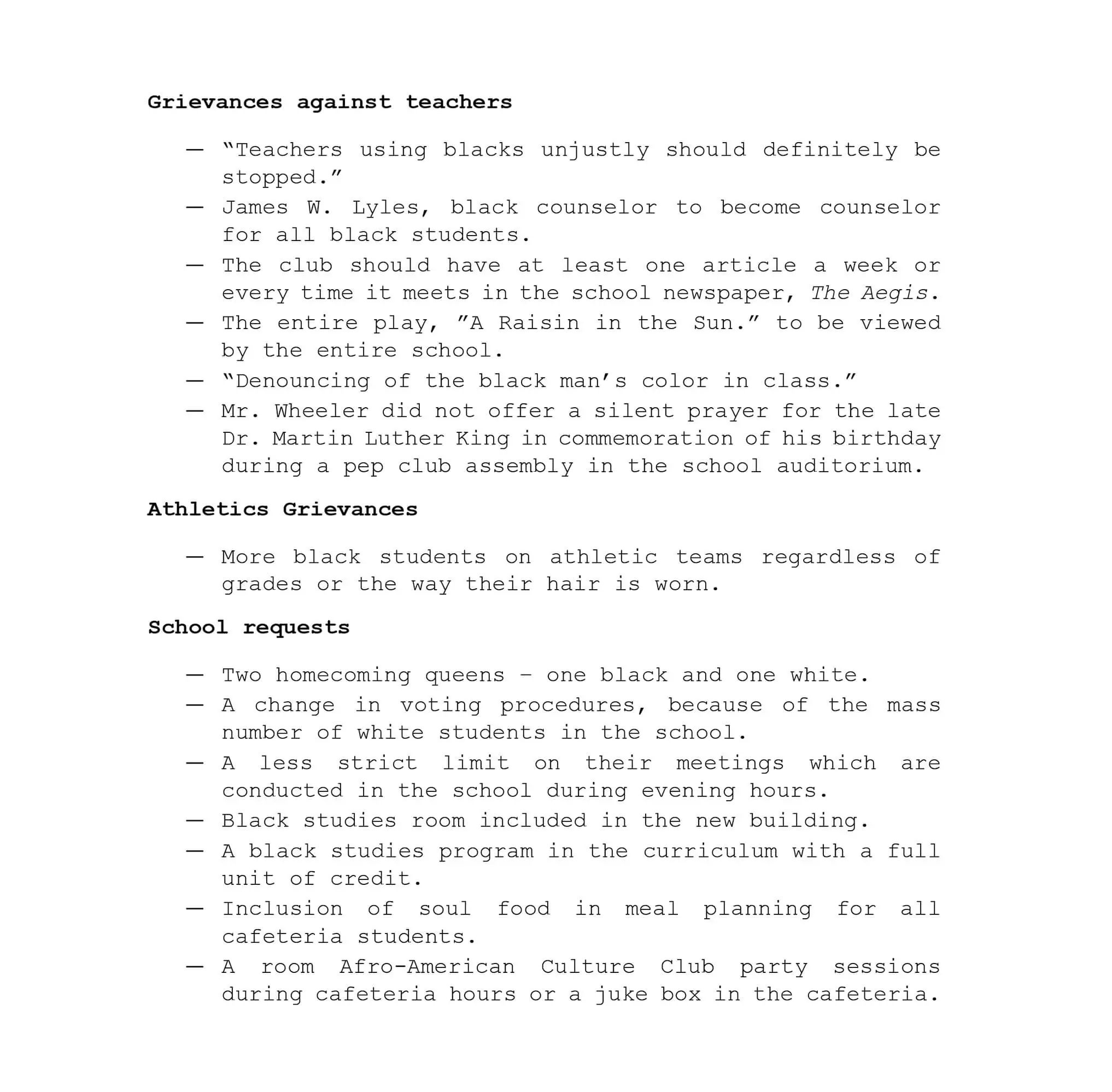

They met in the library and developed a list of grievances and requests, which they presented to the school administration and the Bloomington Pantagraph.

The day after these grievances became public, a group of white students publicly mocked their requests and started a fight.

Though the incident ended quickly, racial tension was growing.

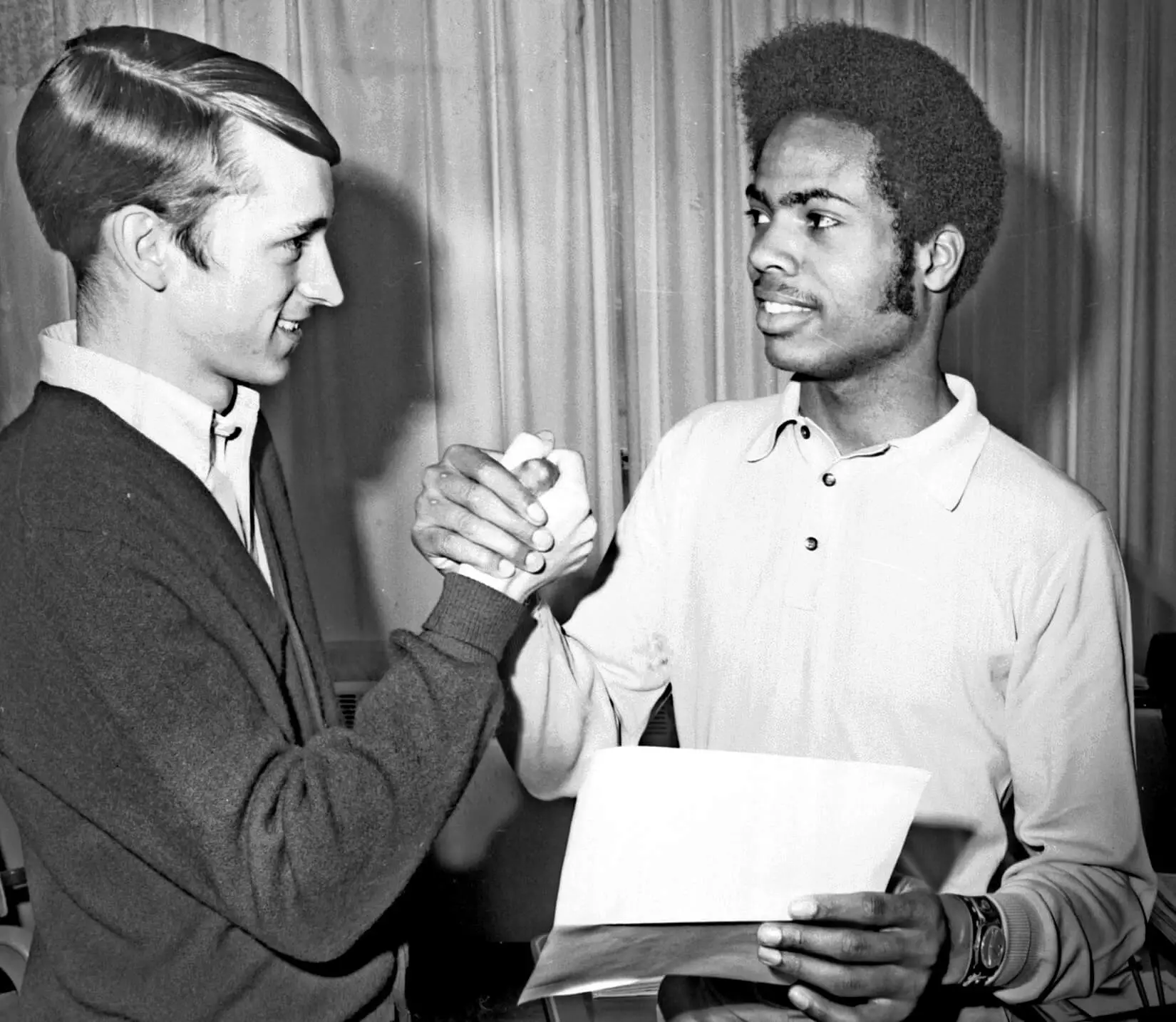

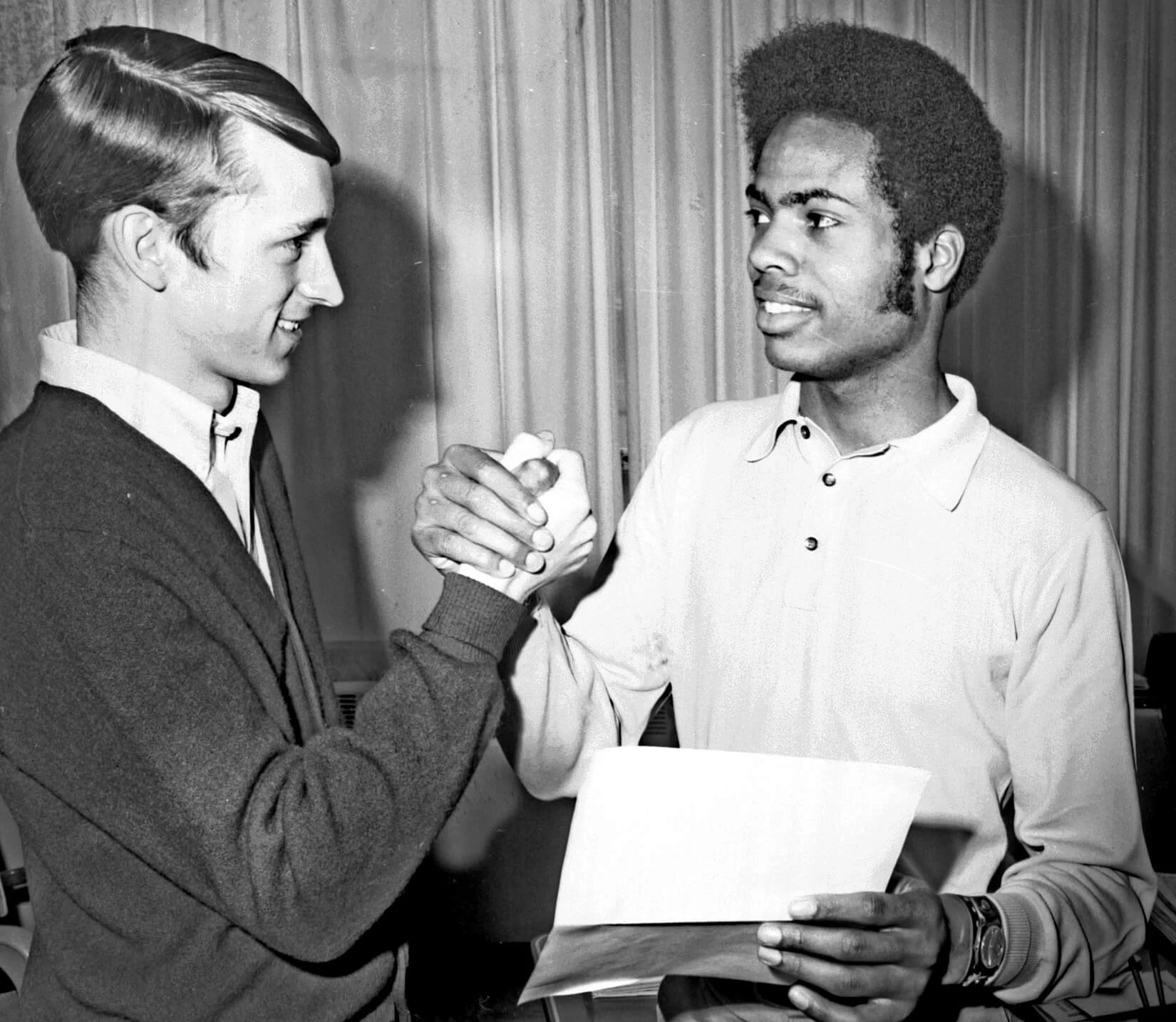

Two days later an understanding between students appeared to have been brokered. But that was not the case.

“We wanted Black History taught in the school. We wanted foods that Black people primarily eat. We said we wanted an assembly because we wanted people to see something of our culture. We wanted our voices heard.”

— Alice Thornton Moss

BNBHP interview, 2018

“My sophomore year I took a bookkeeping class and did pretty well in it. I wanted to go into the next level. My guidance counselor told me, "Well why do you want to do that? You'll probably end up working in a factory..." That was his input. He was trying to put me into a shop class instead of the advanced bookkeeping.”

— Mike Jones, BHS Class of 1970 BNBHP interview, 2018

All-School Assembly

In May the Afro-American Culture Club received permission to have an all-school assembly for the purpose of celebrating and creating a greater understanding of their Black culture and heritage.

The program included the reading of original poems, an African dance number, and a presentation of the play A Raisin in the Sun.

During the presentation to juniors and seniors, about 50 white students decided they did not like the program and tried to leave. There were strict rules regarding assembly behavior and this broke the rules.

The result was another fight. Fearful that someone could get hurt, the police were called. All Black and white students involved in the fight were suspended.

The following morning the police were there with riot gear when fights between white and Black students erupted again.

“I vividly remember a handful of white boys, who were instigators, went out to the north parking lot...they came back around to the south side of the school and they had chains in their hands.”

— Mike Jones

BNBHP interview, 2018

One student had her nose broken, while another was stabbed in the back. An officer was also injured trying to break up a fight.

That afternoon more fights were broken up by police and as many as 75 additional students, both Black and white, were suspended.

Police were asked to be at the school through the end of the school year, while tension between students, as well as faculty, remained high.

Reflection Questions

How would you respond if a group of people got up and walked out during a performance you were giving?

Do you think school leadership was unaware of discrimination at the school, or did they choose to ignore it?

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County