1965

Who had the power to choose where they lived?Department of Urban Renewal

Bloomington’s Department of Urban Renewal wanted to tear down homes on Bloomington’s west side and replace them with low cost, low income housing. They worked with Bloomington-Normal’s business-oriented Citizens Advisory Improvement Committee (CAIC).

Mrs. Louise Pennick

Mrs. Louise Pennick was an 80-year-old African American widow with only $64 per month on which to live. Almost half of that went to pay her monthly mortgage for her small home, which needed repairs.

Members of McLean County’s human rights advocacy groups, including US, Students for a Democratic Society, and the Committee for Social Action, often took up the cause when they learned of local discrimination.

Who had the power?

Pennick's Home Condemned

In November 1965 Louise Pennick’s home at 1714 Illinois Avenue was condemned by the City of Bloomington. An urban renewal officer presented her with a list of required repairs that she had no means to take care of, and told her to abandon her home.

Pennick refused as she had only three payments left on her mortgage. Instead she reached out to US member Carrol Cox for assistance.

Pennick’s request resulted in a full-fledged, well-orchestrated civil rights action against Bloomington’s Urban Renewal office and the members of the CAIC. With Cox in the lead, members of US, ISU’s Students for a Democratic Society, and the Committee for Social Action did everything in their power to save Pennick’s home.

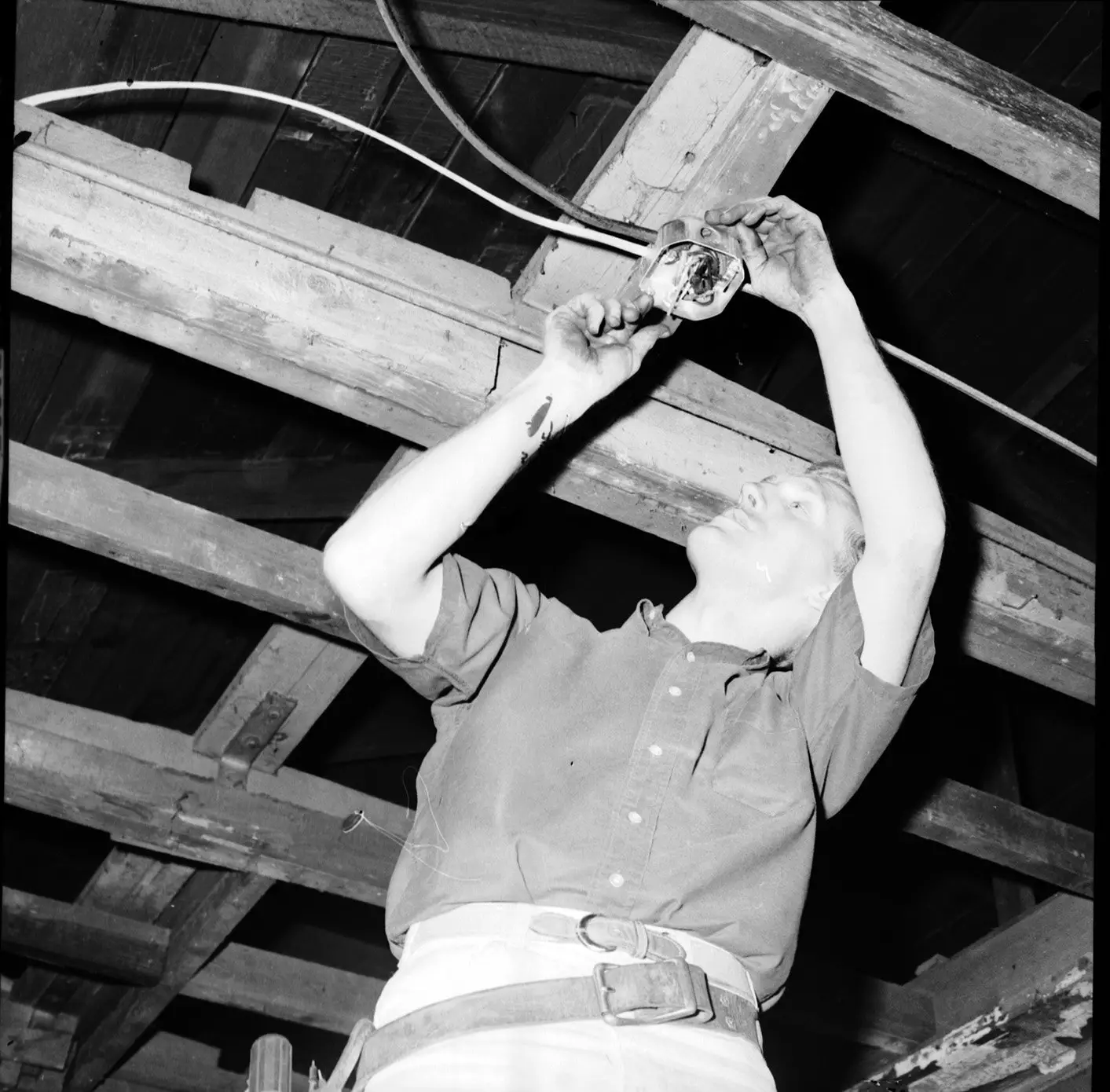

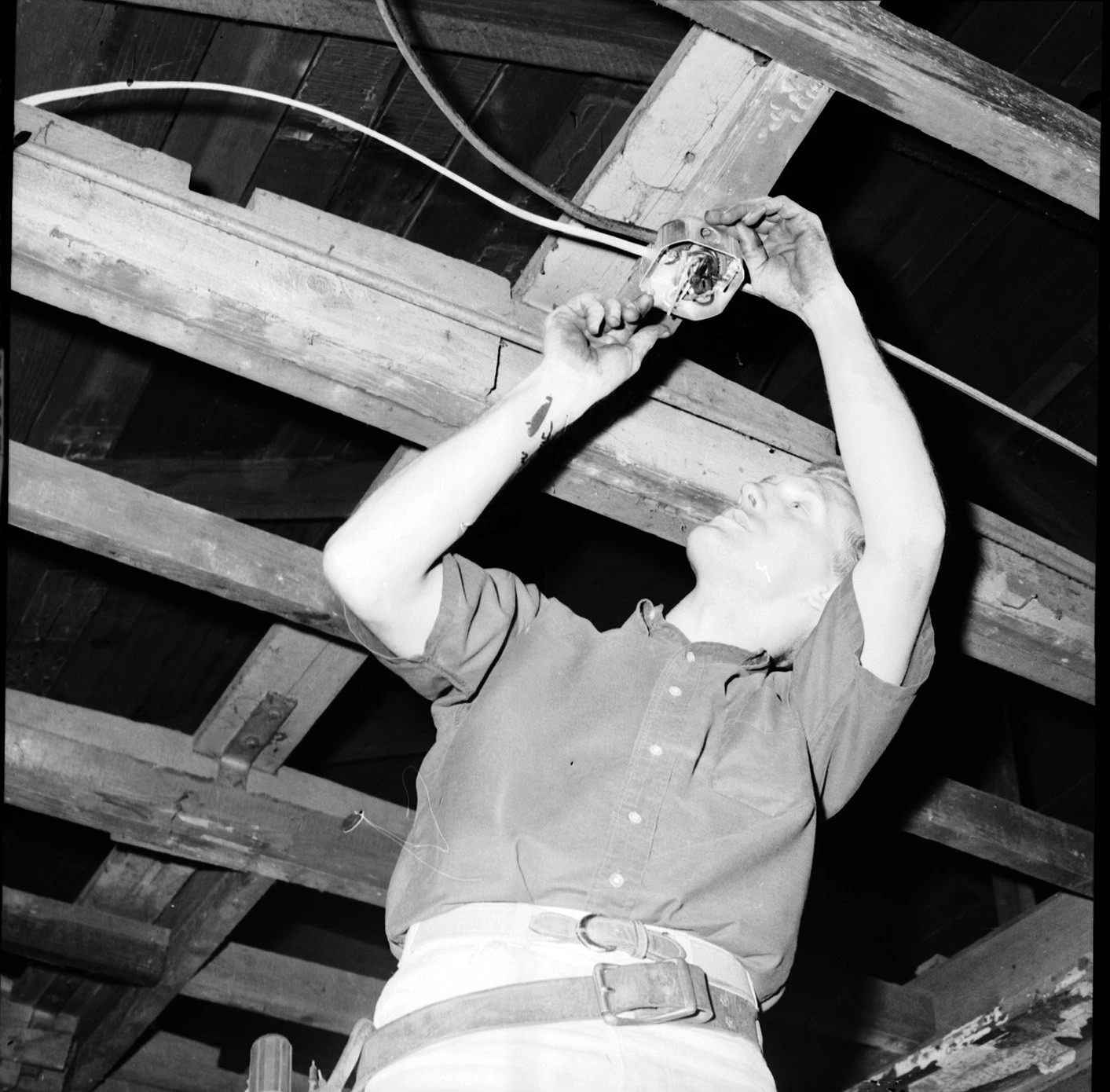

Volunteers Mobilized

A coalition of volunteers mobilized to do the necessary repairs so Pennick would not lose her home.

They collected $1,200; purchased supplies; put on a new roof and downspouts; paneled, plastered, and painted the interior of the home; and installed an adequate bathroom and space heater. A larger heating system was left undone because of low clearance in the basement. The foundation was left alone, as it looked solid to everyone except the inspector.

Delayed, Stonewalled, and Harassed

At every stage of the upgrades and repairs, the Urban Renewal office and its building inspector delayed, stonewalled, and harassed Pennick.

Indifferent to Pennick’s physical and financial limitations, the inspector berated her for her lifestyle and deviance from tidy, middle-class appearances. This included using pictures of her home to illustrate urban blight, and contrasting them with photos of brand new homes in new neighborhoods, where people “took pride in their property.”

In April 1969, with some repairs still undone, Bloomington was ready to finalize its demolition order.

The unfinished repairs included work the city had promised but never delivered — the installation of a sewer connection that Pennick was being charged for even though it had not been installed, and doors with workable locks.

Selective Enforcement of Housing Codes

Members of the coalition who had helped Pennick with repairs organized a plan for the May public hearing.

First they wrote and published, ”Who Stands Condemned?”—a pamphlet that outlined the harassments Pennick had endured and spotlighted the discriminatory injustices that the Urban Renewal Office and the CAIC had subjected her to.

In addition to saving Pennick’s house, the group hoped to show that Bloomington’s selective enforcement of housing codes victimized low-income people and robbed them of their human dignity.

In the week prior to the hearing, the coalition passed out leaflets describing the injustices of the CAIC, and picketed the business locations of its members — two banks, a realtor, a law firm, and a lumber company.

The Hearing

On the night of the hearing, there was standing room only in Bloomington’s City Council chambers.

Student volunteers set up a projector and screen so that color slides of Pennick’s home could be shown.

As images of the newly paneled and painted interior, the new bathroom, the home’s freshly painted exterior, and its new roof and gutters came up on the screen, ISU student John Keller narrated, and all evidence for demolition produced by the Urban Renewal office was disproved.

But when Keller finished the slides of Pennick’s home, he continued with slides taken at the home of the Urban Renewal inspector, showing his defective gutters and downspouts, his trashy front lawn, and his open garage filled to overflowing with junk. They concluded, “This is the house of the man who found code violations at Mrs. Pennick’s... maybe he should inspect his own home.”

The city manager ruled that Pennick could keep her home and continue living there. He told her at the end of the hearing, "You are fortunate in having such committed supporters.”

The hearing went smoothly until City Manager Wes McAllister announced he would rule on the hearing in 30 days. Angered, 25 spectators cornered McAllister behind city councilmen’s seats. They demanded specifics on what qualified a building to be condemned and an immediate decision. They left after a satisfactory response was provided.

Procedures Were Changed

Because the coalition of volunteers and organizations had so well demonstrated that selective housing code enforcement victimized the poor and minorities, Bloomington’s Urban Renewal Office modified its procedures in dealing with housing code violations.

Reflection Questions

Who decided if a home should or should not be condemned and torn down?

What would have happened to Pennick if the decision had been made to condemn her home?

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County