1921

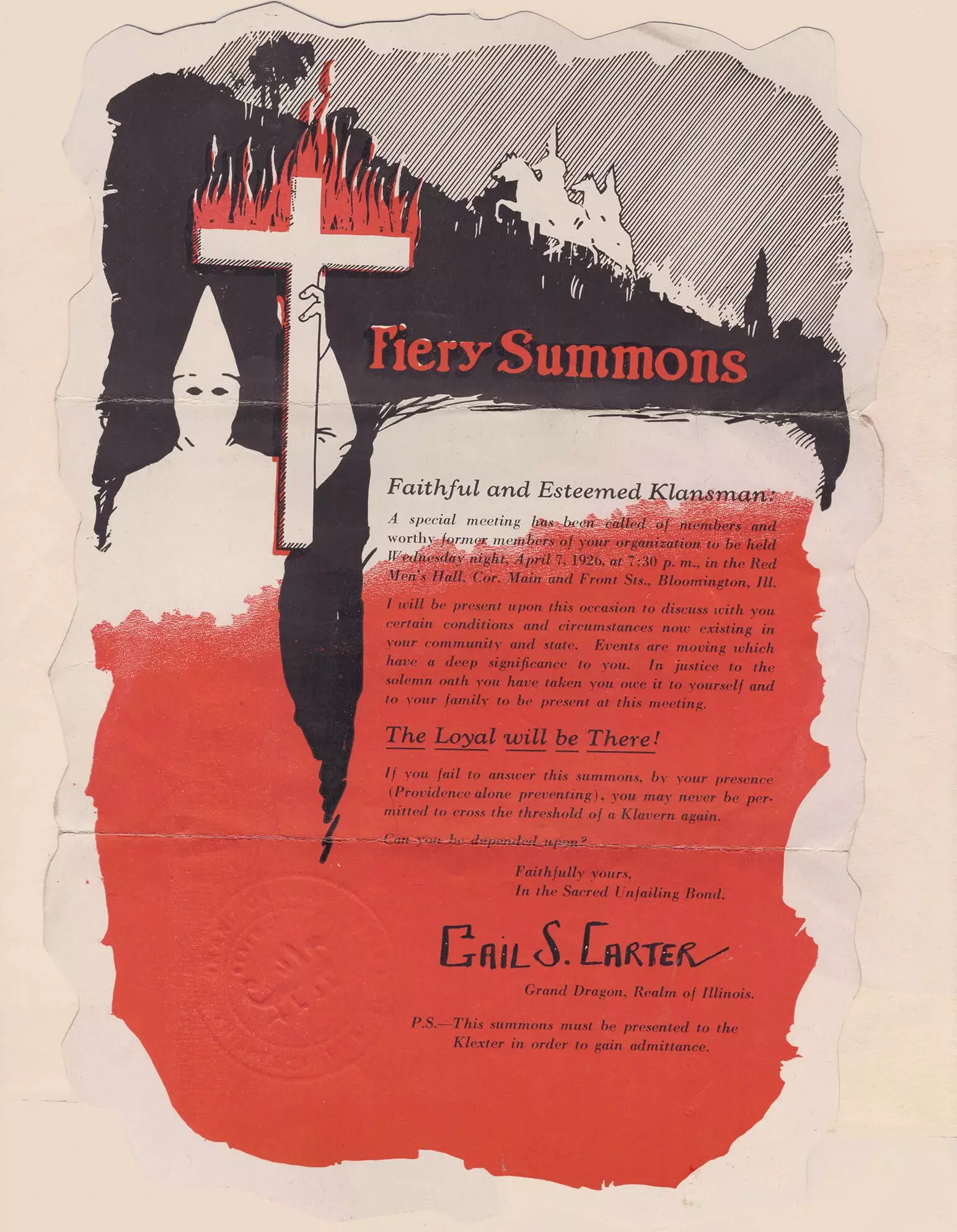

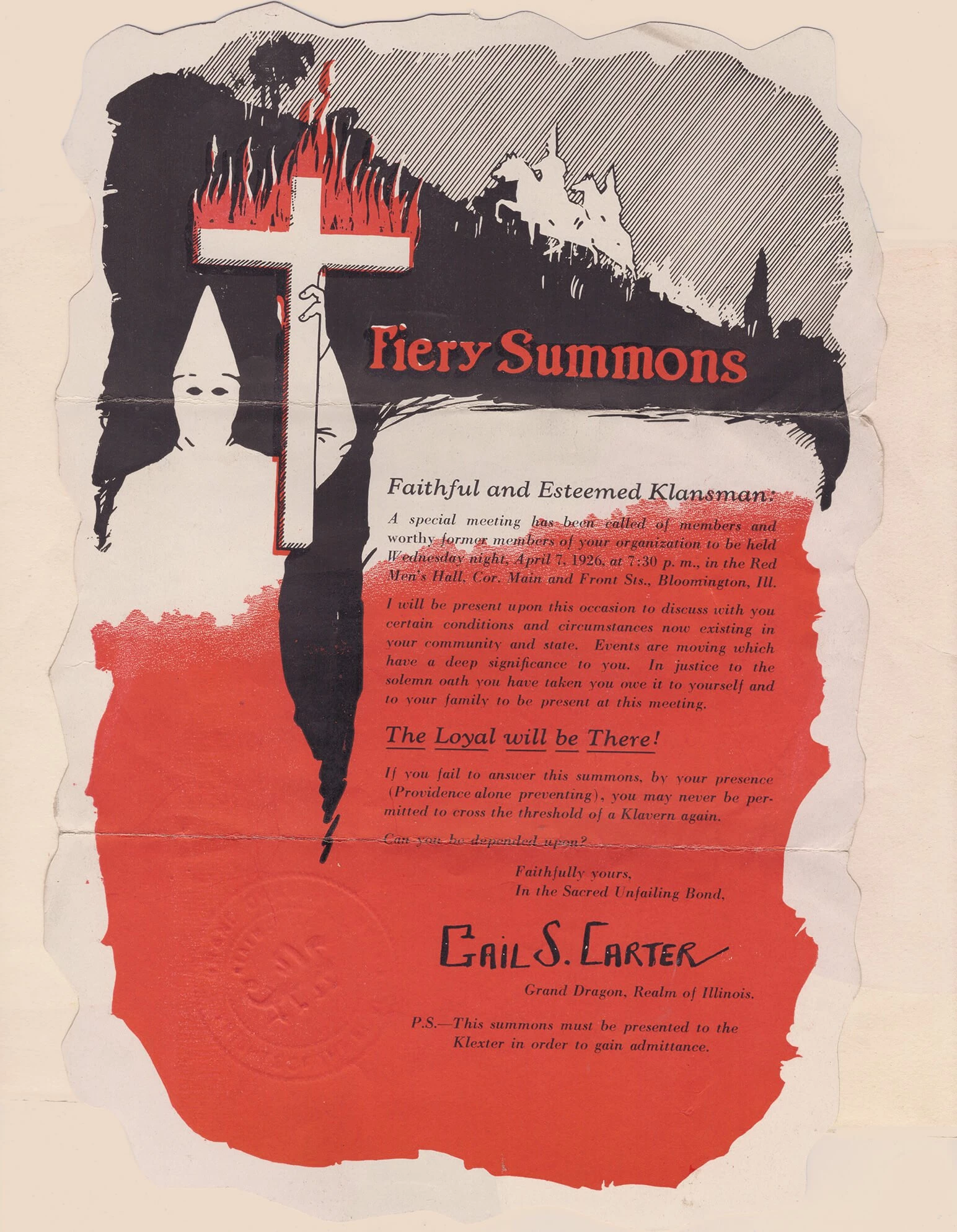

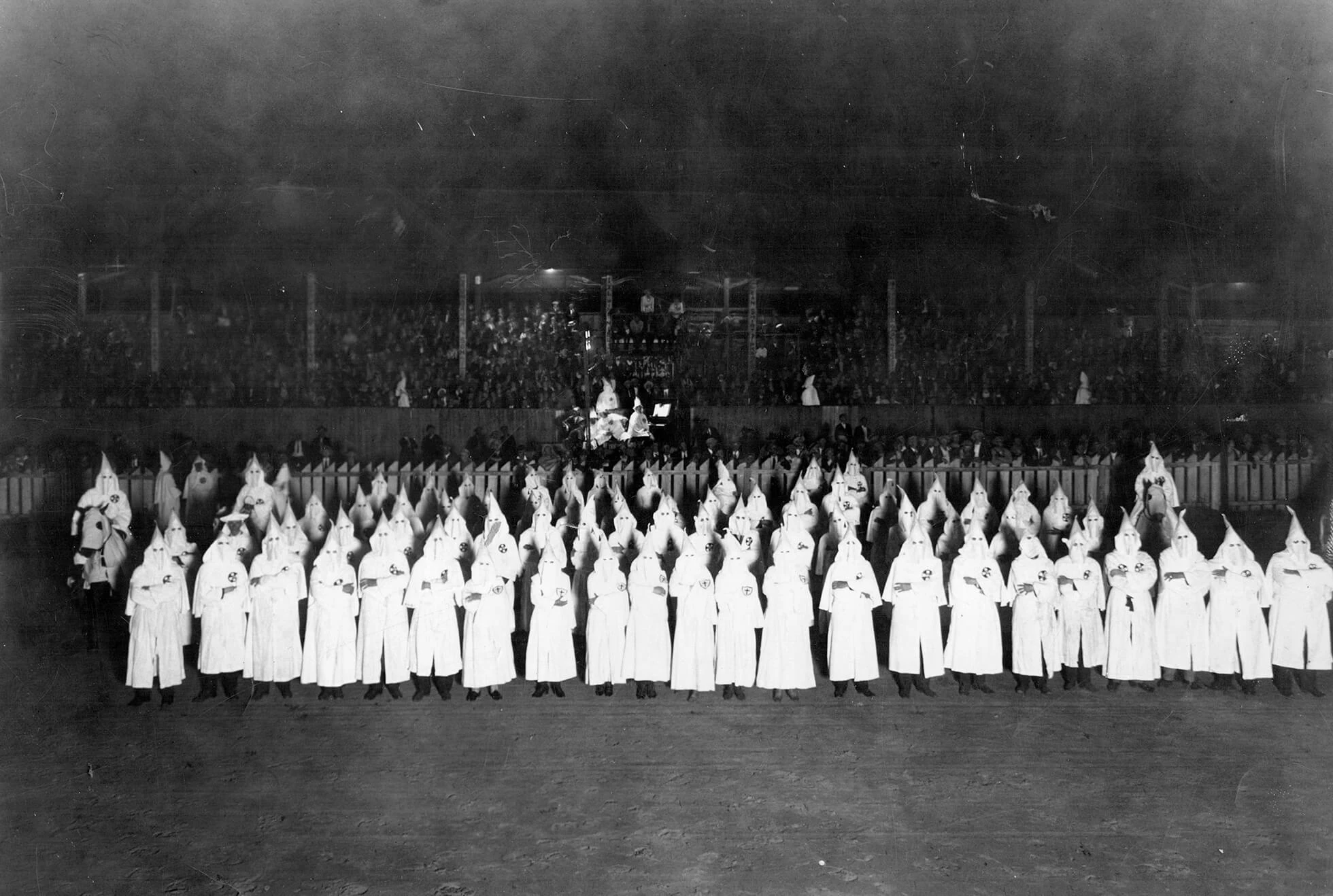

Who had the power to instill fear?The KKK

Self-proclaimed white supremacists, the KKK professed a strong conviction to the U.S. Constitution — as long as Protestant white men remained in control, and that lesser races (Blacks, Irish, Hungarians, Catholics, and Jews) remained subservient.

Non-KKK Members

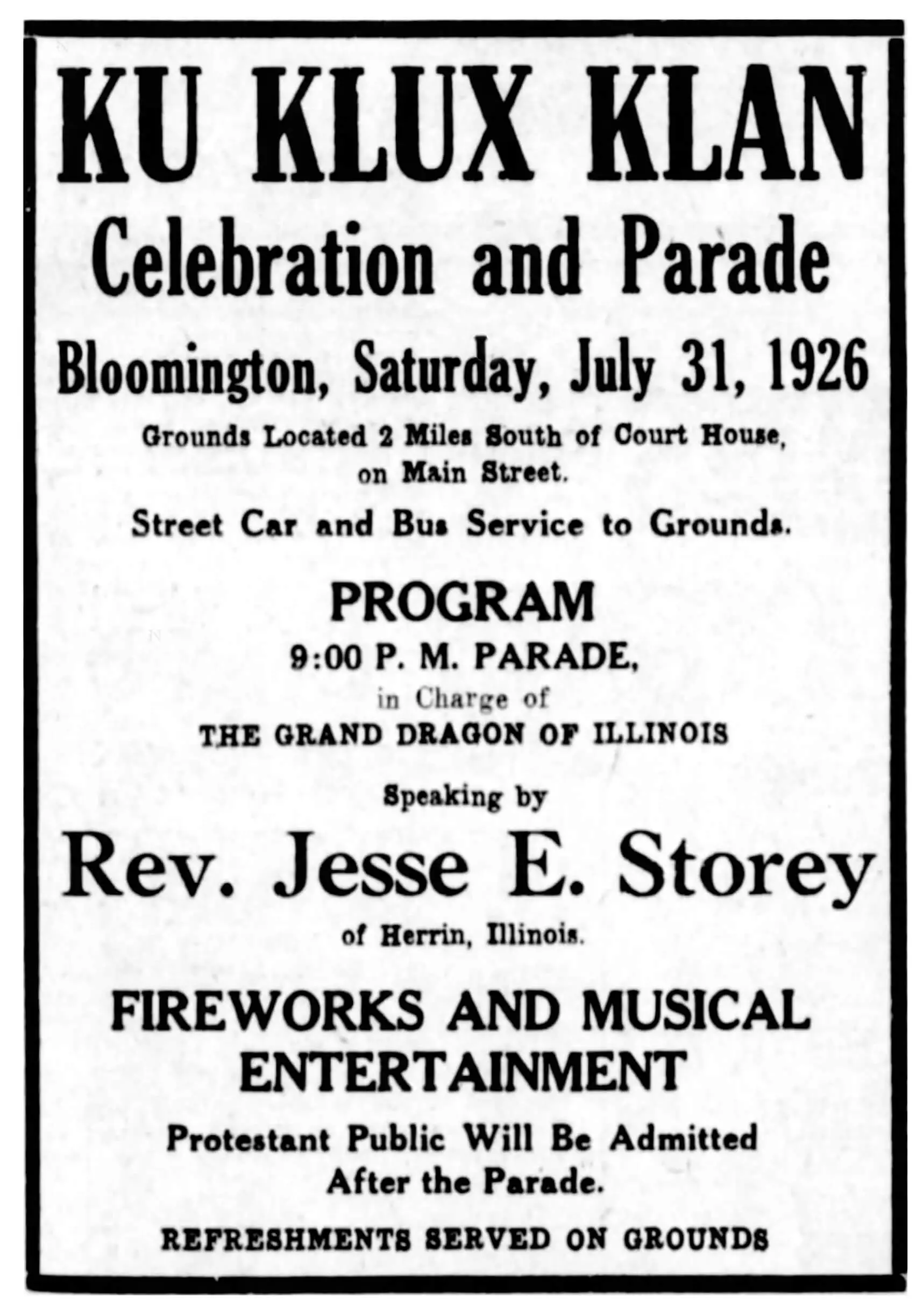

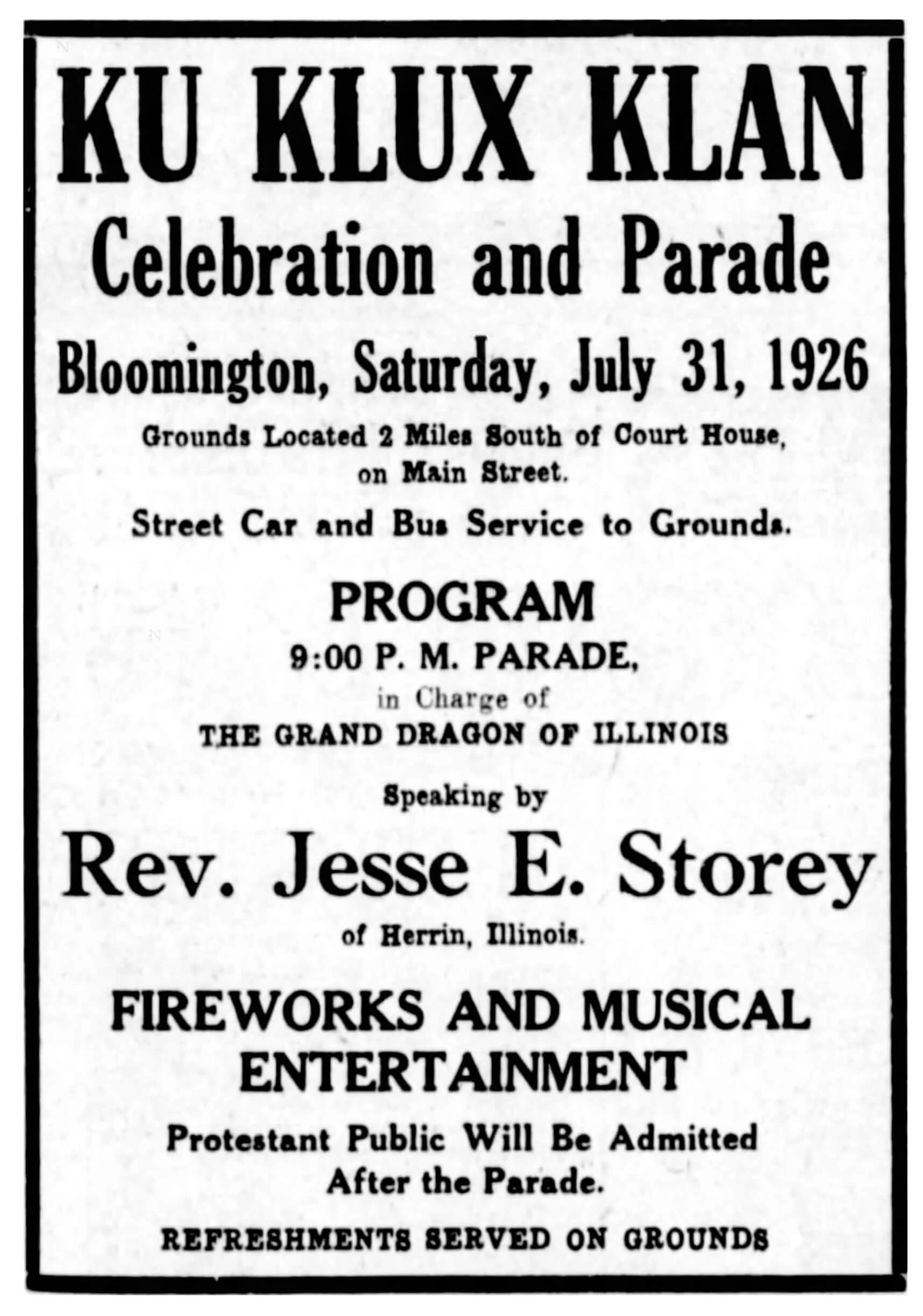

Few non-members of the KKK publicly denounced the activities of the Klan. Some viewed the Klan as a social organization and believed the local groups to be harmless. Some attended Klan rallies in order to witness the spectacular parades and firework displays often featured at these events.

In public local African Americans were quiet about the goings on of the Klan. We don’t know what conversations they had amongst themselves, or what level of fear they experienced. But many had undoubtedly heard of, witnessed, or experienced the horrific practices of the KKK.

A very small number of local residents publicly voiced negative views of the KKK.

Who had the power?

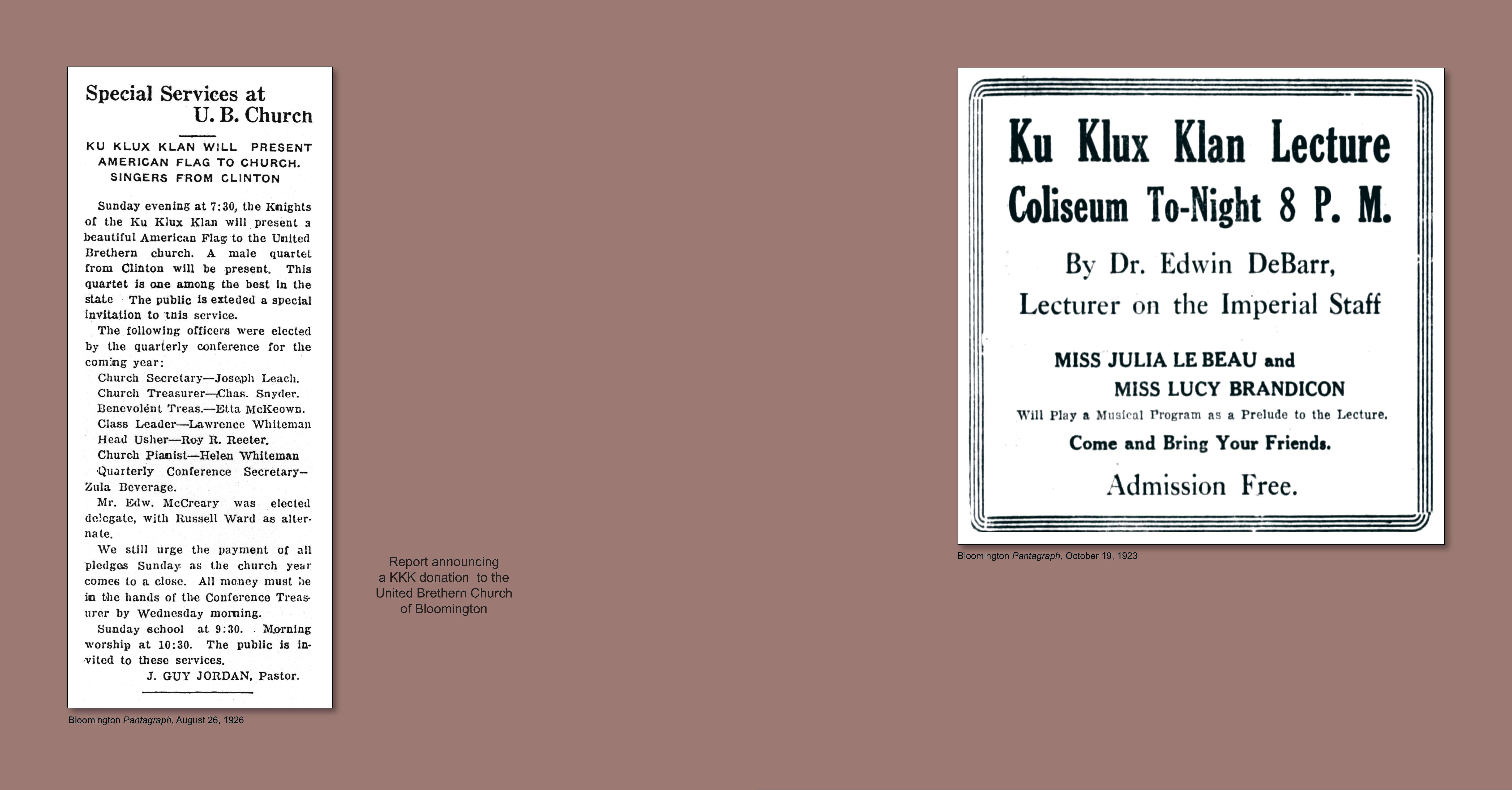

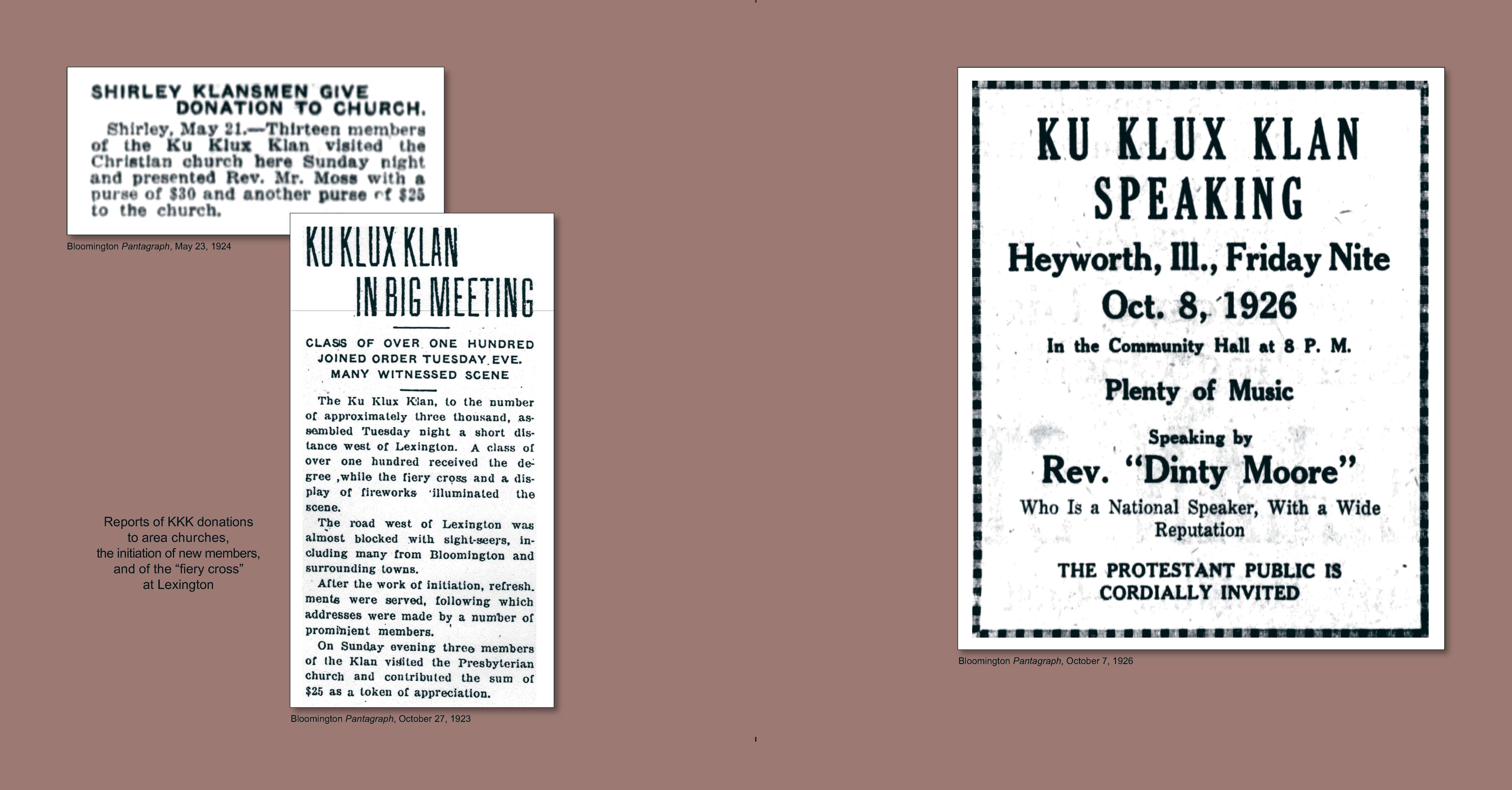

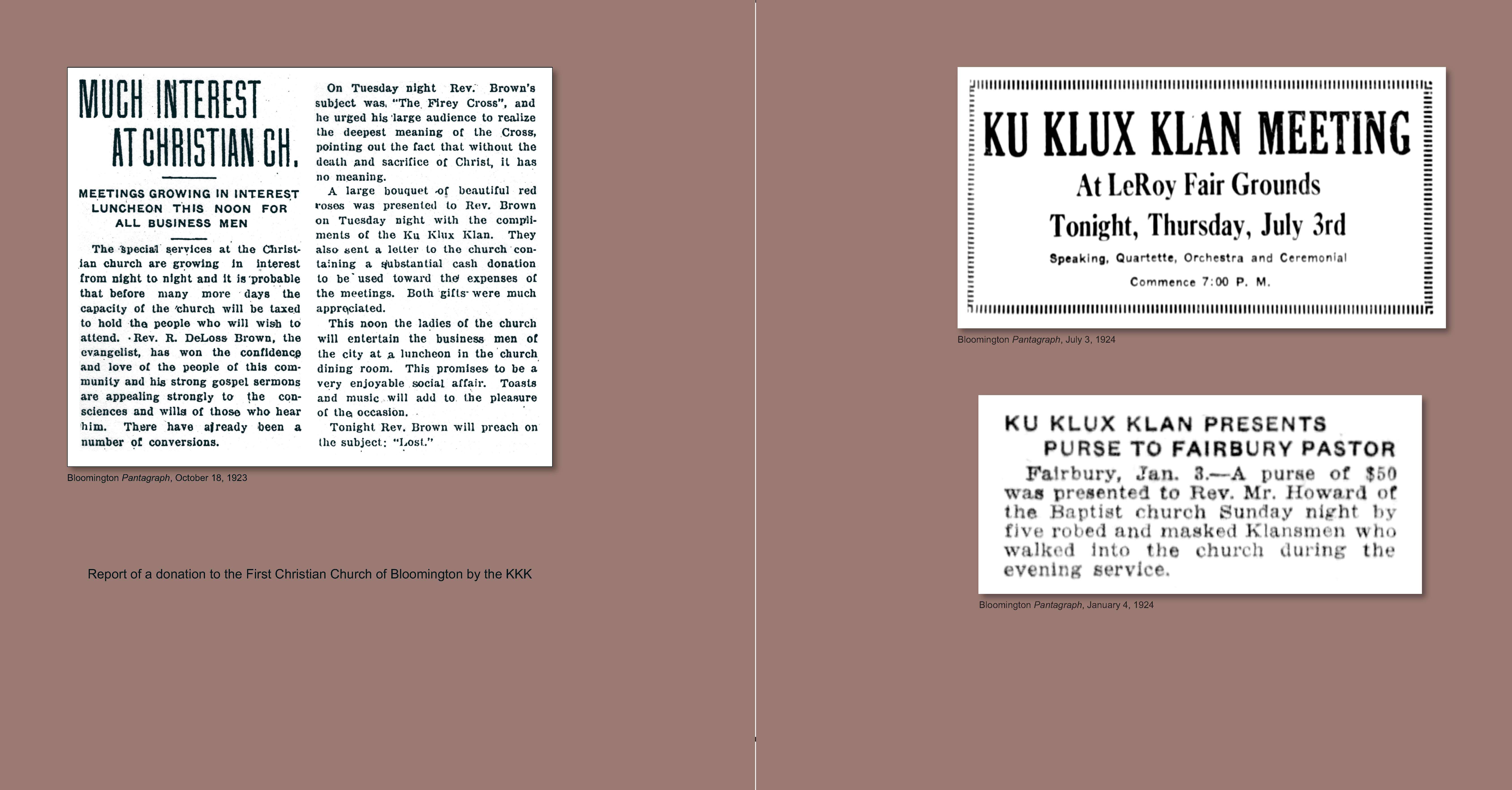

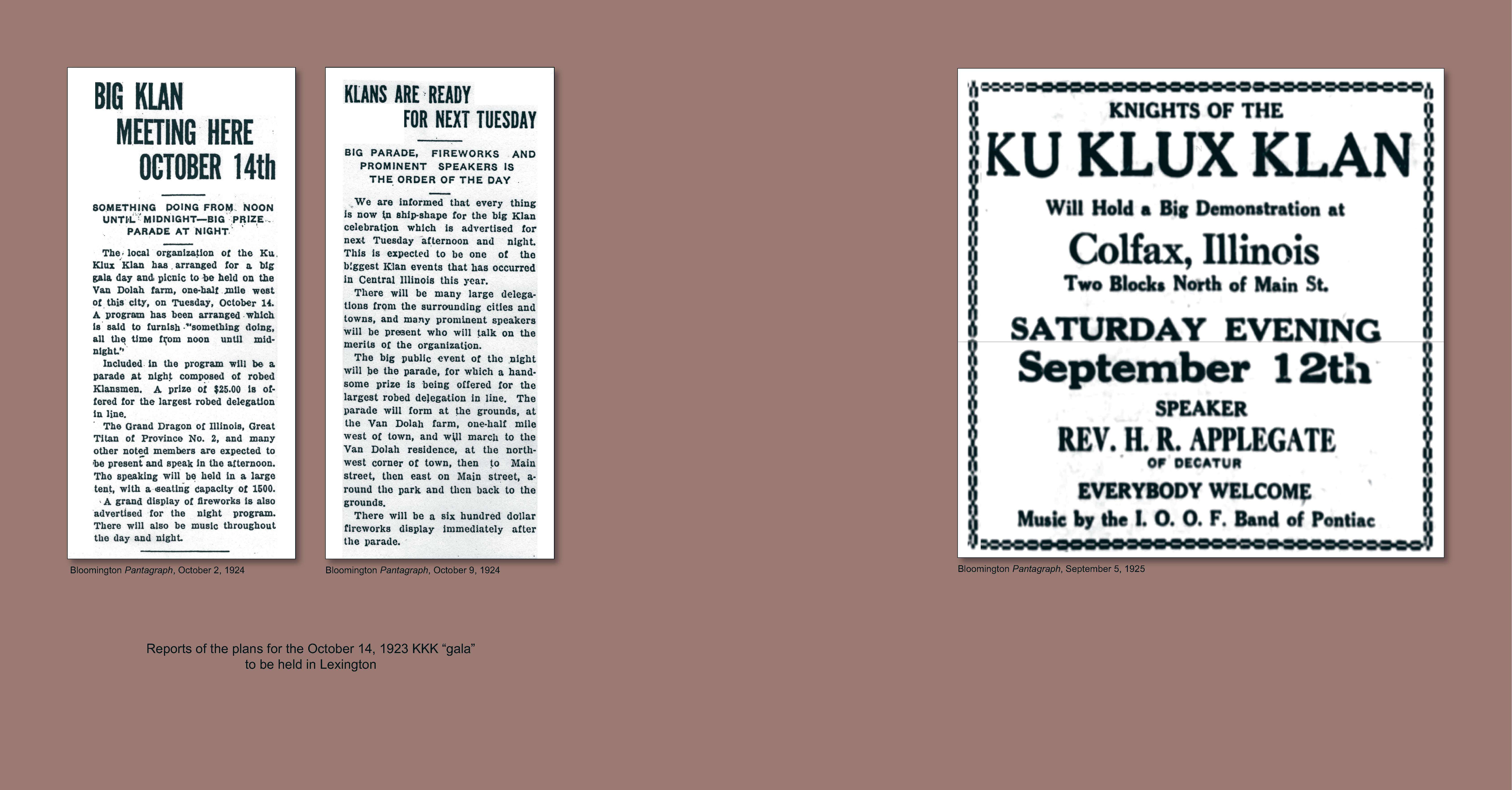

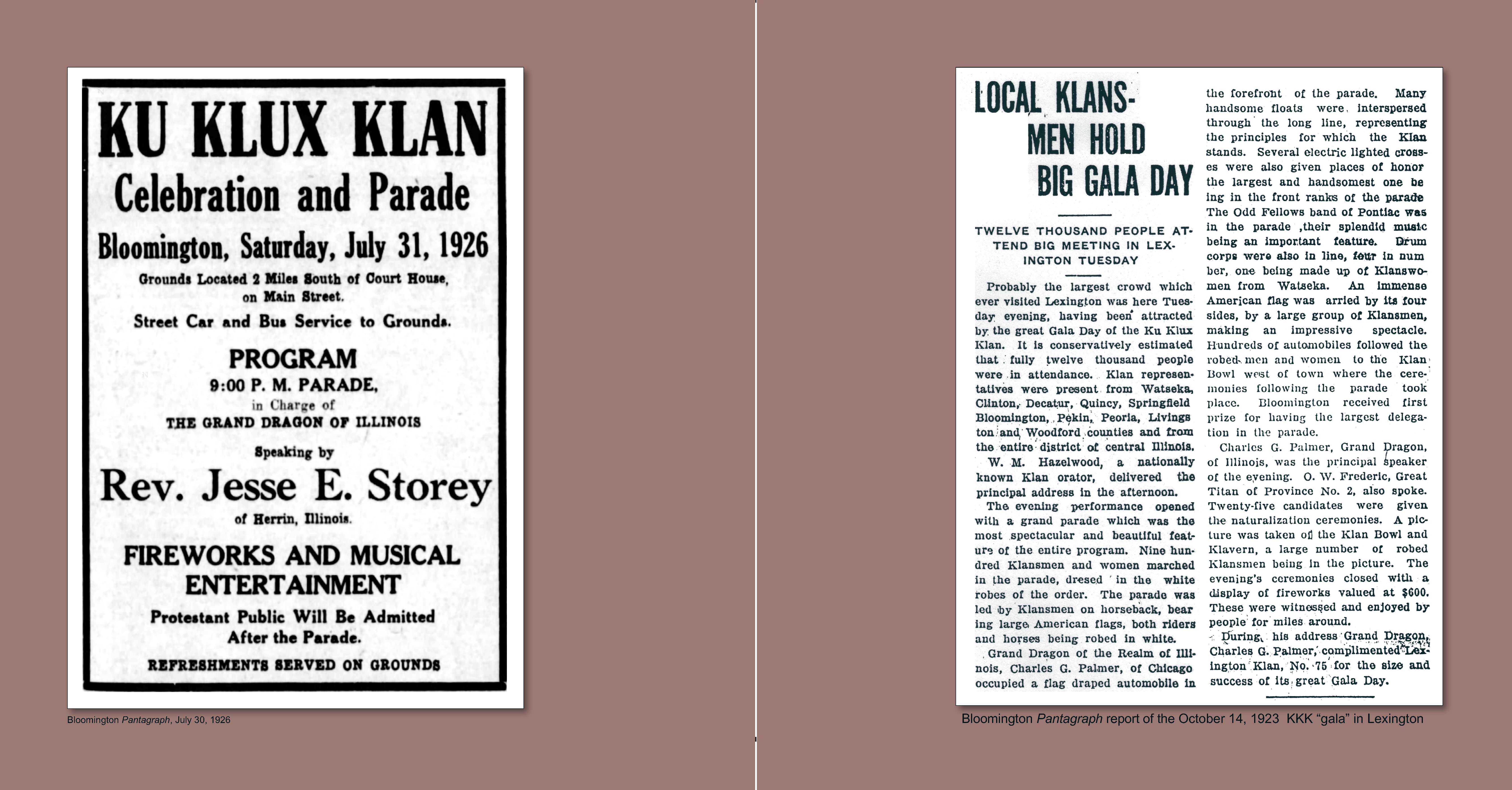

Local membership in the KKK grew quickly, as did media coverage of their events.

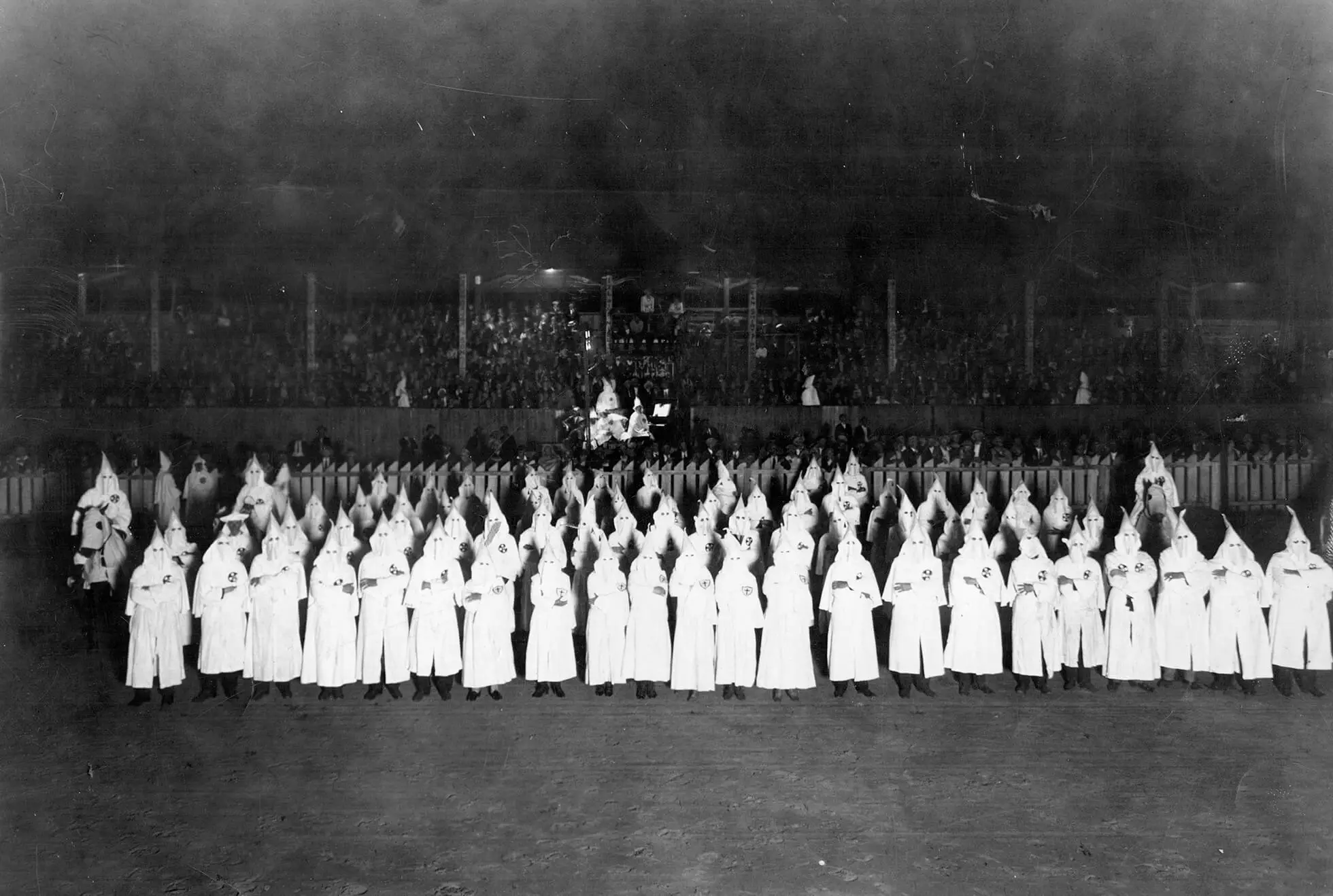

This photo was taken on the Clayton Mays farm northeast of Bloomington (now the southwest corner of Towanda and Jersey avenues), where a “Klaveron” (meeting place) had been constructed by the local Klan for meetings and ceremonies. Shortly after its construction in May 1924, Bloomington’s Pantagraph reported a “large electric cross, some sixty feet in height, upon which floated a huge American flag,” had been added. When illuminated it “was visible for many miles.”

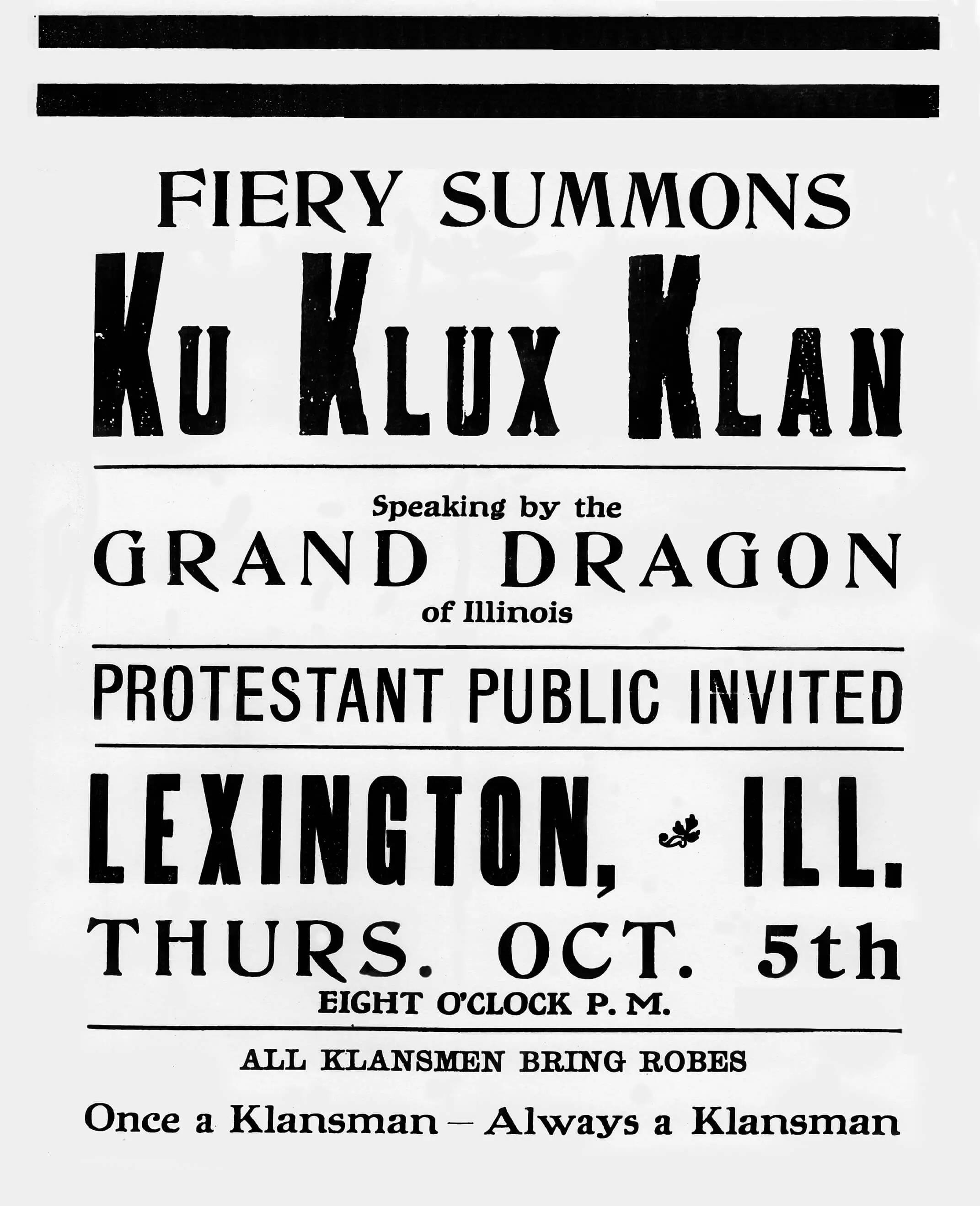

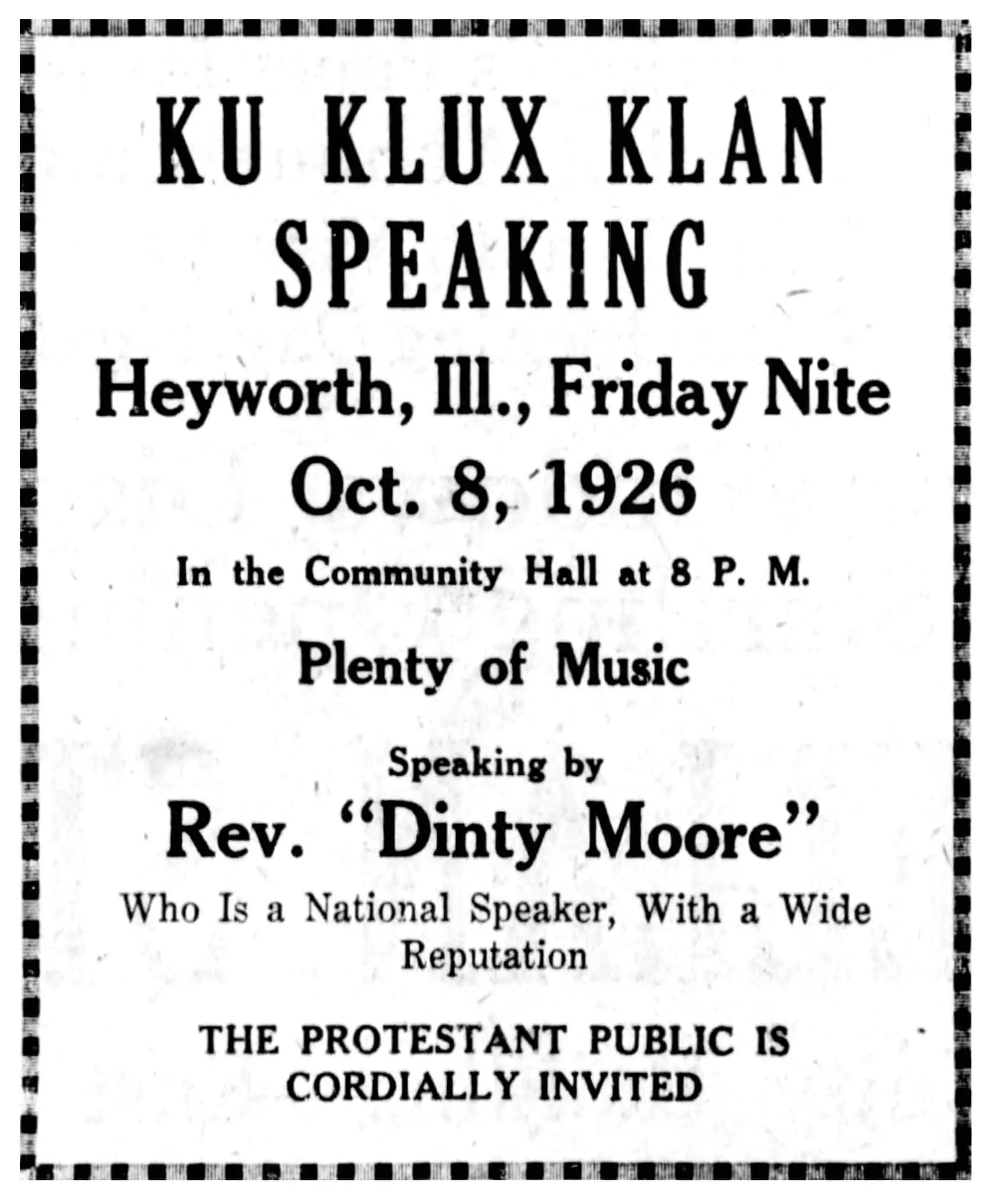

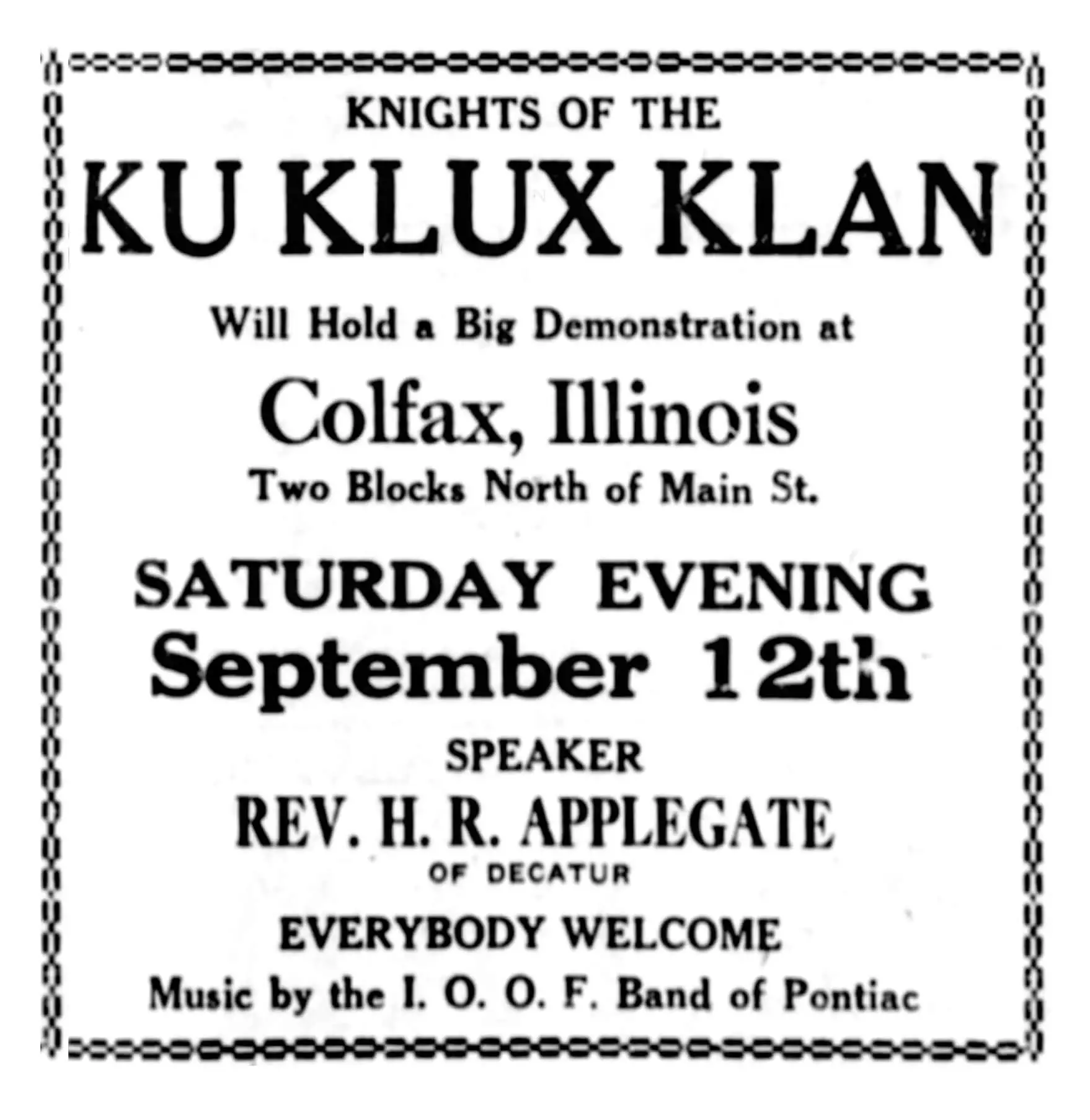

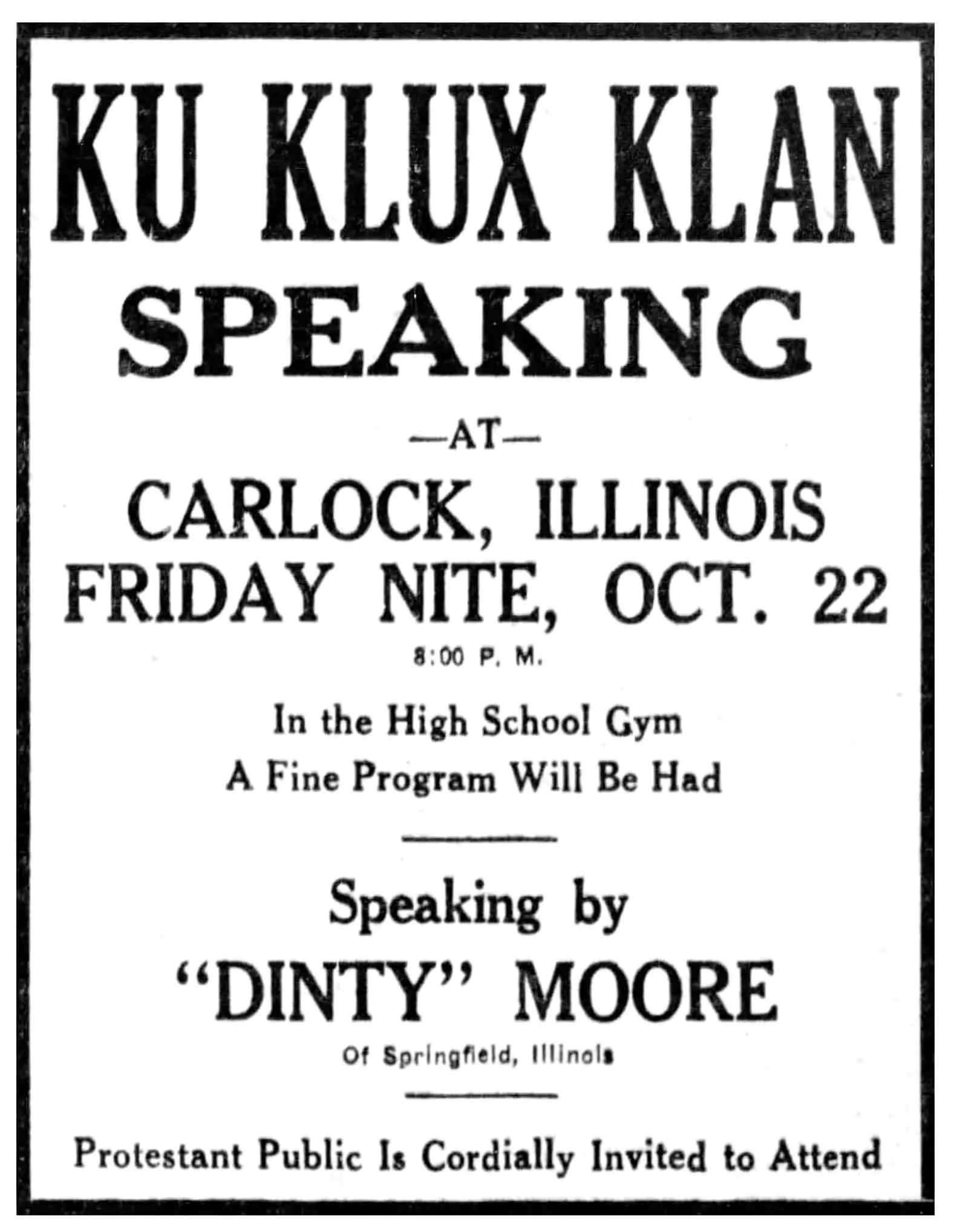

Local KKK events included speakers, parades, and firework displays that sometimes drew thousands of spectators.

On October 10, 1924, the Lexington KKK, led by Grand Dragon Jim Van Dolah, held a Gala Day that drew a crowd of 12,000 members and spectators.

The parade featured masked and robed Klan groups from across Central Illinois, the Grand Dragon of the Realm of Illinois, Charles G. Palmer riding in a flag draped car, floats representing the principles of the Klan, several electric lighted crosses, and Pontiac’s Odd Fellows band.

Bloomington won the award for the largest delegation.

Bloomington resident Clinton Burkholtz was one of hundreds of McLean County residents who joined the KKK.

His diary notes that he joined in June 1926, when local membership in the Klan was at its height, and was initiated that October. Burkholtz attended many meetings and rallies, including an August 20, 1927 grand meeting and parade in Lexington.

In January 1928 he was appointed Klaliff (vice-president) of the Bloomington Klan.

A few months later, entries in his diary noting his involvement in the Klan stopped.

Local resident Joe Landis did not believe the KKK was good.

In 1923 he self-published a searing statement on his views of Klan members.

“I want to tell you...your hypocritical mouthing about your super-patriotism and 100% Americanism, about your love of the flag and your reverence-for the Constitution are, in the judgment of all sensible citizens, a travesty on consistency and an insult to common sense... [you are] hypocrites, office-seekers, fanatics and fools who constitute a hooded-gang of cowardly miscreants.”

— Joe Landis

The Patriot, November 1923

After 1925, stories of violent acts and threats made by Klansmen in the south, including scattered threats in Central Illinois, began to appear in Bloomington newspapers.

Soon local residents started to question the ethics of the Klan and Illinois politicians launched legislation against the group.

Flip through this book to see advertisements and reports published in the Bloomington Pantagraph about area KKK activities and events.

Use the arrows (or the arrow keys on your keyboard) to flip through the pages.

Bloomington’s Klan disbanded in February 1928 and reorganized as the Knights of the Great Forest. The group ceased to wear the white robes and regalia of the Klan.

Reflection Questions

Imagine yourself living in the 1920s. If you saw a large group of individuals dressed like this, what emotions would you experience?

What methods did the KKK use to effectively attract new members?

Why did this group’s public activity suddenly decrease?

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County