For the better part of four decades, friends Jacob Welby Bucher and Charles Carroll Fell of Bloomington performed as the popular vaudeville song and dance act, “Welby and Pearl.” From the mid-1870s and into the early 1900s, the two hoofers often performed in blackface with nationally touring minstrel shows.

Bucher and Fell, according to one account, left sleepy Bloomington for the bright lights of Chicago in the mid-1870s while still in their teens, fast earning a reputation as first-rate cloggers. “They soon dropped white face and took up minstrelsy, and it was then that they made their greatest hit,” noted a posthumous tribute to the song-and-dance duo.

The Fells are one of the more distinguished and prominent families in McLean County history. Charles Carroll Fell’s long minstrel career as “Carroll Pearl” had been all but forgotten until recently, when local historian Rochelle Gridley unearthed this fascinating (and troubling to today’s sensibilities) story of a Bloomington boy in blackface who made good.

Pearl’s father, Kersey Fell, was a younger brother to Jesse Fell, one of the founders of Normal and namesake of Illinois State University’s Fell Hall, as well as Fell Avenue and Fort Jesse Road. Kersey, like Jesse, practiced law for a time in Bloomington. And like his brother Jesse, Kersey left his legal practice to make a tidy sum in real estate and land speculation.

Kersey married Jane Price and the couple had eight children, five of whom were boys. The Fells were a rather serious lot, all things considered. Born in 1857, Charles Carroll was the exception. “The other boys became staid businessmen but Carroll had a roving streak, and the glamour of the footlights proved irresistible,” noted The Pantagraph upon his death in 1925.

After the Civil War and continuing into the 20th century, vaudeville was a wildly popular form of public entertainment. Traveling troupes offered a seemingly endless array of performers and performances—standup comedians and pratfall-laden burlesque; acrobats and jugglers; impersonators; feats of strength; animal acts; and, first and foremost, music—with song and dance numbers center stage.

Ethnic humor, much of stereotypical, also defined vaudeville, especially, and most perniciously, minstrelsy. In this nakedly racist form of entertainment, white entertainers blackened their faces and used exaggerated black English to depict American Americans as lazy, childlike and other characteristic grotesqueries. By infantilizing black people, white America could mock—while simultaneously expropriating—black culture.

Jacob Welby Bucher and Charles Carroll Fell’s views regarding African Americans, racist or otherwise, are unknown. Although it may be hard to believe today, some blackface entertainers regarded their performances as unconnected to larger issues of race or racism, let alone political or civil rights or larger issues of social justice. And some who “donned the charcoal” even believed they were, in a way, paying homage to black culture and tradition.

As one of the longest running acts of the era, Welby and Pearl traveled the length and breadth of the U.S. and beyond many times over, earning a national reputation for their clogging routines with various vaudeville and minstrel companies.

From available evidence, the two entertainers began their long career in 1874 or 1875. By September 1876, “Welby and Pearl” were part of a larger troupe that enjoyed a long run at the Coliseum, an arena-like venue located at the corner of State and Washington streets in the heart of downtown Chicago. Shows were nightly, seven days a week, with a matinee on Sunday. “Balcony especially reserved for ladies and their escorts,” read one advertisement.

By the following summer of 1877, Welby and Pearl were with Harry Robinson’s Minstrels, a company featuring Robinson’s “burlesque trapeze;” Lem H. Wiley’s Silver Cornet Band; Billy McAllister’s “Dutch comicalities” and “Tyrolean warbling;” Tommy Sadler’s baby elephants; George Robinson’s female impersonations; and the “quintette clog” or “silver statue clog” of Welby and Pearl and three additional hoofers—Sadler, Stiles and Goodyear.

In November 1877, The Vicksburg (Mississippi) Herald newspaper reported that Robinson’s “admirable array of Ethiopian talent” (the term Ethiopian was often employed as a synonym for black) performed before the “largest and most generally appreciative” audience ever gathered at the city’s opera house.

Yet such was the theater business that hard-earned dollars could be lost as fast as they could be made. By early November 1878, Harry Robinson’s minstrel company was bankrupt and disbanded, so Welby and Pearl were back in Bloomington, reduced to being the beneficiaries of a charity show organized by their friends and associates and staged at downtown’s Durley Hall.

Yet such was the business, also, that one was never down and out for good, especially if you were as talented and hardworking as Welby and Pearl. And sure enough, in two months time the pair found themselves back on the road, this time with McAllister’s Minstrels, appearing in the likes of Terre Haute, Ind. and elsewhere.

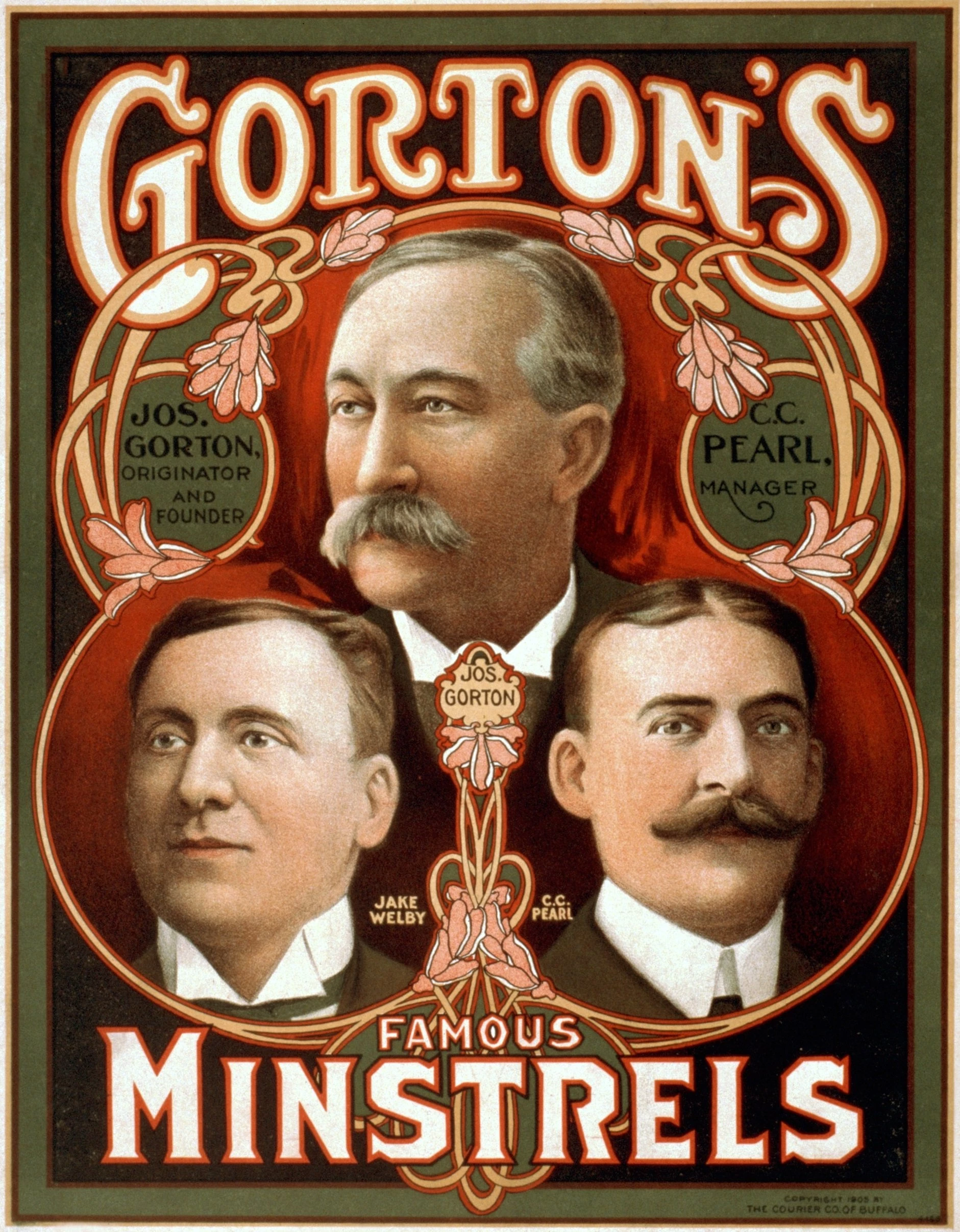

By the turn of the last century, if not earlier, Welby and Pearl were associated with the Gorton’s Minstrels, a popular touring company in which they also had a financial stake. In February 1902, the entertainers passed through Bloomington to visit friends and renew old acquaintances. According to The Pantagraph, the two song and dance men had just wrapped up a 183-week tour with Gorton’s company, which traveled by way of a private railcar with its own wait staff and chef.

Welby and Pearl were still appearing with Gorton’s Minstrels as late as 1908, nearly three and a half decades after the two embarked on their joined-at-the-hip stage career. Longevity of this kind in a business as notoriously volatile as theater was rare indeed. And in fact, the two continued to perform together, especially in the Chicago area, until Jacob Welby Bucher’s death from Bright’s disease in 1915. He passed away in Chicago but was buried in Pontiac, home of his brother.

Charles Carroll Fell died ten years later in Virginia. “The silvery chords that enthralled thousands during the forty years of his stage career, will be heard no more,” eulogized The Pantagraph. “The curtain has fallen, but in many hearts, the memory of this sweet singer and Adonis of the stage, can never fade.”

The curtain has long fallen on minstrelsy, now universally vilified and rejected as a despicable art form. But what has not faded are the hard lessons its popularity tells us about how racism is fundamentally and inextricably intertwined with the story of America—both in Welby and Pearl’s time and in our own.