The Vietnam War, it’s been said, was fought on two fronts—in Southeast Asia and back home, especially on college campuses.

On April 30, 1970, President Richard Nixon announced his decision to send U.S. troops into Cambodia to engage Vietcong elements that were active on both sides of the Cambodian-South Vietnamese border. For many, this represented a reckless escalation of an already unpopular war.

Nixon’s decision was met with widespread unrest, culminating on May 4 when Ohio National Guardsmen killed four protesters at Kent State University.

The following day, some 200 Illinois State University students occupied Hovey Hall, the school’s administration building. Eventually, about 75 students cornered President Samuel Braden in the office of the dean of students. Looking to defuse the situation, Braden agreed to demands that included lowering the ISU flag to half-mast for six days for Kent State, as well as for Mark Clark and Fred Hampton, Black Panther leaders killed the year before in Chicago. Furthermore, he also agreed to lower the flag on May 19 for the birthday of slain black leader Malcolm X.

“The university deplores the incident at Kent State University,” Braden’s carefully worded statement read, “at which innocent students were killed, apparently in the course of expressing their legal and peaceful concern for new and unexamined developments in our foreign policy.” He also indicated that students were free, during the next week, to pursue “other forms of peaceful activity” in response to Kent State, even if that did not include attending classes.

The same day students occupied Hovey Hall, May 5, a fight broke out near the flagpole on the ISU Quad between war protesters and a campus club composed of Vietnam veterans.

Although Illinois State weathered its share of marches, rallies, and street scuffles, it was the only public university to remain open throughout the long, turbulent month of May 1970.

The flagpole served as the focal point for a month of battles, both literal and figurative, between anti-war students and those who either supported Nixon’s decision or simply opposed student radicalism. President Braden was criticized for capitulating to student radicals, though to the consternation of pro-war (or anti anti-war) residents and students, he remained unapologetic. “You can say that the flag flies at half-staff over an open university here, while it flies over closed universities across the land,” he said.

The May 6 Pantagraph featured two photographs of the American flag, one showing student protesters at the Massachusetts National Guard headquarters tearing it into strips to make arm bands, and the other showing U.S. airborne troops in Pleiku, South Vietnam, rallying around it before heading off to Cambodia. “Restraint is the misbegotten word of the decade,” The Pantagraph observed. “Those pledged to make war [on campus] must be deprived of a battlefield, expelled; but those who peacefully assemble must be protected. The sorting-out task is a sobering one.”

On that same day, students marched to Normal’s Fairview Park to hold a memorial service for the Kent State four. That morning, someone or some group cut the flagpole ropes and hoisted a banner that read, “National Guard 4. Kent State 0.” Later in the day, a melee broke out after three protesters brought a Vietcong flag to the site.

While vandalism plagued ISU the entire month, most of the incidents were relatively minor. University staff stayed in campus buildings overnight to prevent mischief, and members of the Academic Senate patrolled the Quad from midnight to 6 a.m. Illinois Wesleyan University, though, was not so lucky, as two fires set at Presser Hall caused more than $150,000 in damage.

On Monday, May 11, Republican state senators called Braden to Springfield for a dressing down. At issue was why he buckled under the demands of student radicals. “I would not characterize it as being a friendly discussion,” Braden said after the closed-door Republican caucus. Alan Dixon, Democratic state senator from Belleville, was not as diplomatic, describing the meeting as “the grossest violation of academic freedom.”

Two days later, Wednesday, May 13, students began vociferously protesting a curfew set by the Town of Normal. At 11 p.m., Braden spoke to about 3,000 students gathered on the Quad. “I’d rather that you would go home and go to bed, but I am going to be here all night and you can be, too, if you want to be,” he said. “If we can keep it on the campus, we can show what we have here at ISU—an open university.”

Despite Braden’s plea, students and police clashed for several hours on School Street in front of Hovey Hall. Rocks were hurled at police, who responded with swinging nightsticks. Normal Mayor Charles L. Baugh finally agreed to lift the curfew at 4:15 a.m., a move that quieted the protesters. Fortunately, combatants on both sides sustained only minor injuries.

Yet throughout the long month, a sense of normalcy prevailed on the Normal campus. Most of the school’s 14,000 students continued to attend classes, for example, even though they were given the choice to skip them for a week.

On May 15, more than 4,000 folks crowded into McCormick Hall’s gymnasium for a patriotic rally organized by a group of students referring to themselves as the “no longer silent majority.” Speakers included Mayor Baugh and Gen. Richard T. Dunn, a Bloomington lawyer and Illinois National Guard commander. The group submitted a list of requests to Braden, which included the continued right of ISU police to carry firearms and the erection of an all-weather, properly lit flag which would fly 24 hours.

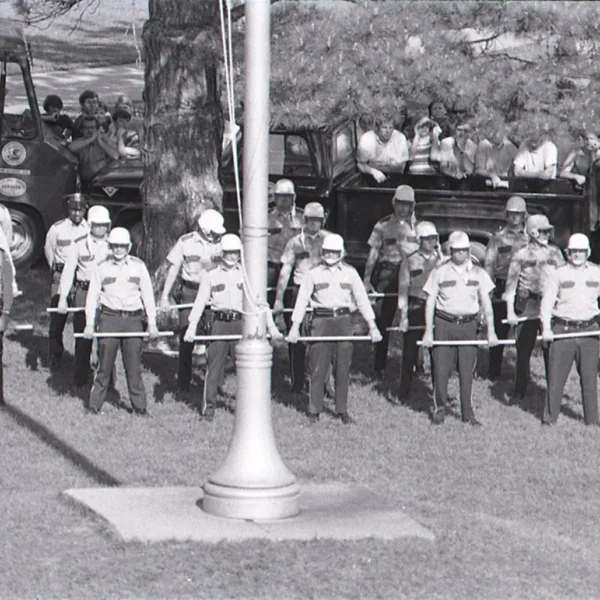

Tensions increased again on Tuesday, May 19, when a group of construction workers raised the flag, which was supposed to be at half-staff for Malcolm X’s birthday. In response, ISU officials lowered the flag and ringed the flagpole with university vehicles. Braden, who stood inside with 44 ISU police officers and sheriff’s deputies, told the “hard hats” that anyone venturing inside the cordon would be arrested.

Less than a week later, Braden backed a resolution calling for a national week of “mourning and unity” for servicemen killed in Vietnam. He balked, though, at calls to dismiss Carrol B. Cox of the English department. “If we dismissed every person whose out-of-class activity proved unpopular to the administration or community, we’d in effect be abdicating our role of a university in society,” he said.

Although President Braden received a fair amount of scorn on both the right and left, he kept the campus open, calling that achievement “one of the proudest stories in the history of this institution.” For some critics, the end did not justify the means. Due in part to pressure from Springfield, Braden resigned as president just one month after the protests.