The Civil War was a brutal, decidedly unromantic slog. By its cruel end, as Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee’s armies blackened the Virginia countryside in a death match costing thousands upon thousands of lives, the four-year conflict had become a harbinger of World War I and the tactics and machinery of mass killing.

On the other hand, the dashing cavalryman, sash tied around waist and sword held aloft (glinting in the sunlight, no less), remains an iconic image of the Civil War, though this figure is better suited to the supposedly more chivalric Napoleonic era of a half-century earlier.

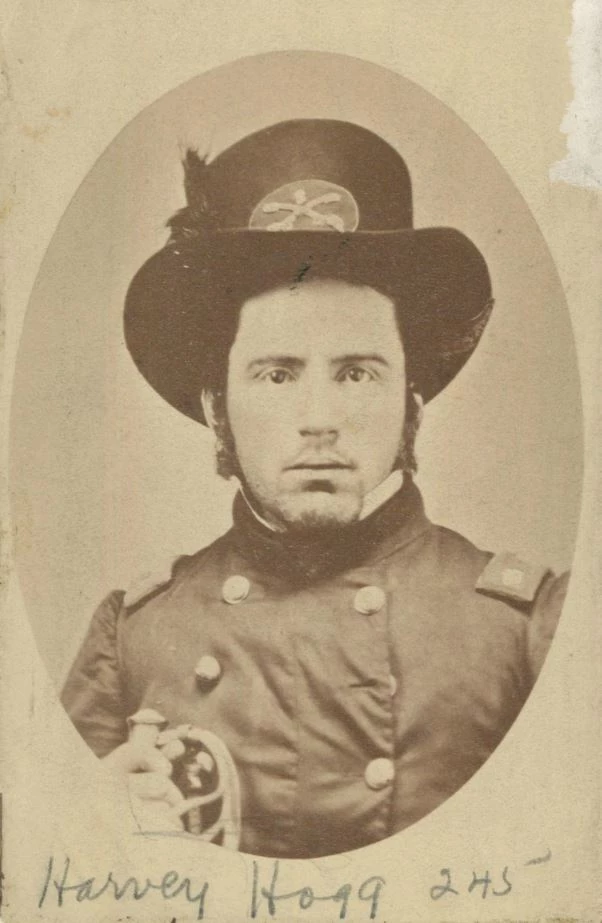

Even so, the Civil War provided plenty of larger-than-life stories of beau ideal cavalry officers. Locally, this archetype is best represented in the life and death of Lt. Col. Harvey Hogg of the 2nd Illinois Calvary. Handsome (think Elvis Presley), recklessly brave and perhaps a touch naive, Hogg died leading a doomed cavalry charge in western Tennessee. His death on August 30, 1862, gave his adopted hometown of Bloomington a war hero and martyr to the Union cause.

Born in 1833 in Smith County, Tenn., east of Nashville, Hogg was raised by an uncle and attended schools in Tennessee and Virginia. Coming from a slave-owning family, he was that rarest of men in the Antebellum South—an outspoken opponent of the “peculiar institution.” Hogg’s dissertation at a college in Emory, Va., for example, was on the “Evils of Slavery,” a topic that drew the ire of the school’s faculty and president—and presumably many of his fellow students. For his part, Hogg was said to have answered back that “if I speak at all, I shall speak my honest convictions.” He then studied law at Cumberland University in Lebanon, Tenn., graduating as class valedictorian.

Hogg moved to Bloomington with his wife Prudence Allcorn in the mid-1850s, and local tradition has it that he freed his last slave, “Aunt Sarah,” by bringing her to Bloomington.

Yet there’s also evidence, albeit unsubstantiated, that Hogg brought Aunt Sarah to Illinois without “officially” freeing her (though the fact that she was living in Illinois made her a free person by default). When he ran for state representative in 1860, the Illinois Statesmen, a Bloomington weekly newspaper, reported that an African-American woman had fled the Hogg household. Why? According to the Statesmen, which admittedly was an “organ” of the Democratic Party (Hogg was a Republican), there were reports that this woman (likely Sarah) had overheard Hogg talk about selling her back into bondage in the South. There were even more pernicious rumors to the effect that he had already done so.

What’s more likely is that Harvey and Prudie Hogg never told Sarah that she was a free person, and so once she learned the truth she left their house and went looking for work and a new life elsewhere.

In 1857, Hogg formed a legal partnership with Ward H. Lamon, who would become President Abraham Lincoln’s trusted bodyguard in Washington, D.C. Lamon and Hogg’s office was above a drugstore at the corner of Center and Washington streets, on the south side of the courthouse square (this building still stands, and today is occupied by Scharnett Associates Architects).

A successful attorney with a promising political career representing the newly formed anti-slavery Republican Party, Hogg was on the prosecuting team alongside Lincoln for the sensational murder trial of Isaac Wyant (they would lose the case).

Hogg served as city attorney and prosecutor for the Eighth Judicial Circuit, and right before the war was a Republican state representative. Despite the unsubstantiated rumors involving Aunt Sarah, The Pantagraph described Hogg as “a consistent, conscientious, determined anti-slavery man,” albeit one who expressed his beliefs “without being fanatical.”

The 2nd Illinois Cavalry organized in the summer of 1861, with Hogg as the second-in-charge lieutenant colonel. He had a decided flair for the dramatic. For instance, on the evening of March 2, 1862, he left Paducah, KY, with a small force, having learned that Rebel troops had earlier evacuated the Mississippi River community of Columbus, Ky., some 40 miles away. Before heading out, he warned his men that they might run into the enemy. “If we do,” Hogg declared, “don’t use your pistols, but give them the cold steel. The saber is the weapon for cavalry to reply upon.”

“In everything Col. Hogg was a manly man,” read one of several “man-crush” tributes from his contemporaries. “Physically he was one of the finest men I ever saw; about six feet high, finely proportioned, straight as an arrow, dark hair and eyes and swarthy complexion. He was a man born to command, a natural leader.”

At one point during the war Hogg returned to Bloomington to care for his ailing wife and then accompany her to Tennessee, “that she might have the care of her mother and relatives, in her last sickness.” She passed away on May 27, 1862, and Hogg brought her body back to Bloomington for burial

The maelstrom of war cared not a whit for personal grief, so the young widower returned to duty. On August 30, 1862, Lt. Col. Hogg and part of the 2nd Illinois Cavalry arrived in Bolivar, Tenn., located about 70 miles east of Memphis. It was there that Hogg and a mix of Union cavalry and infantry ran into the advance of a large Confederate force. Hogg refused to retreat, instead calling his men forward with a shout of “give them cold steel boys.” According to the adjutant general’s report, the 29-year-old lieutenant colonel was hit nine times by Rebel fire. Others killed in the charge included Sgt. William Ross of LeRoy.

Hogg’s body was escorted back to Bloomington, and the September 14 funeral was said to be one of the largest in the city’s history, up to that time. The procession to the city cemetery (now Evergreen Memorial) included military companies, 55 carriages and a large number of residents on foot. He was laid to rest next to Prudie and their infant daughter Mattie.

“Colonel Hogg was none too good a sacrifice for the principles he died to save,” noted The Pantagraph of September 24, 1862, “but, like many others, he was too good a citizen and soldier for us to spare.” The eulogy concluded with a poem of unrestrained sentimentality common to the era. “His soul released upsoaring,” Hogg was now …

Where armies clash no more,

And peace shall reign forever.