Ellen B. Ferguson, who made Bloomington-Normal her home in the 1870s, was a remarkable but ultimately inscrutable champion of women’s suffrage and feminist ideals.

Born in Cambridge, England, Ferguson had a first-rate education, though whether formal or mostly informal is unknown. Her father, William Lombe Brooke, was a “lawyer of considerable reputation and social prominence.” At one time, Ellen led classes in “French, Latin, German, drawing, elocution, drama, and music.”

In 1860, she and her husband of three years, Dr. William Ferguson of London, emigrated to the U.S. The couple first ran a newspaper in Eaton, Ohio, but by the early 1870s they had settled in the Twin Cities.

Ellen Ferguson first earned a name for herself locally as a lecturer to all-female audiences on women’s health, physiology and similarly “delicate” subjects (delicate, that is, to Victorian sensibilities.) Ferguson and her lectures attracted the attention and interest of the community’s better-educated, upper-middle class sisterhood, represented by Bloomington’s social lionesses Gertrude Lewis Fifer and Mary Enos Gridley.

It was those two women and nine others who signed an open letter to The Pantagraph in the summer of 1871 commending Ferguson’s work and encouraging others to sign-up for her health talks. “We do feel that woman’s needs, her wants—her whole being cannot be more clearly portrayed than has been in this course and in a manner so clear and delicate that the most fastidious cannot take offence,” read the letter. Clearly, local women were starved for forthright and accurate information on gynecological medicine and related issues.

“Dr.” Ferguson (her name often appeared accompanied with that professional title) was more than a popular lecturer on women’s health. She was also one of Bloomington-Normal’s more active suffragists. She played, for instance, a leading role in the Illinois Women’s Suffrage Association’s third annual meeting, held Feb. 13-14, 1872, at Herman Schroeder's Opera House in downtown Bloomington. Other speakers included Mary Adelle Hazlett of Michigan and the celebrated Susan B. Anthony of New York.

On the second day of the statewide meeting, Ferguson followed Anthony’s half hour opening speech. “She inveighed against the practice of taxation without representation,” noted The Pantagraph of Ferguson “She thought no woman should pay any more tax until she was granted a vote.”

Ferguson, however, “spoke principally concerning the frivolity of fashionable life to which so many girls are brought up,” added The Pantagraph. “They are educated too much in the direction of finery and feathers and not enough in the direction of useful information and the knowledge of how to take care of themselves.” Clearly, Ferguson was an unabashed feminist unafraid to challenge the patriarchal constrictions of American society—many of which, let it be said, remain stubbornly in place 146 years after this Bloomington suffrage meeting!

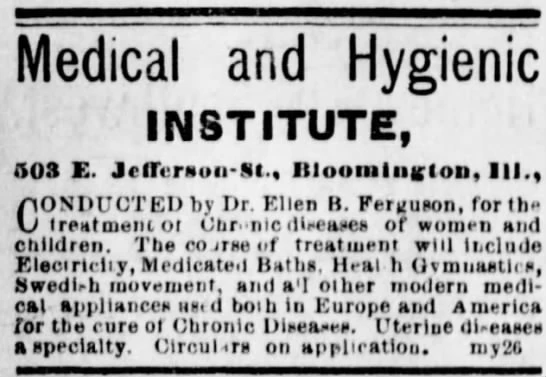

Sometime in 1873, if not earlier, Ferguson established a medical institute on the 500 block of East Jefferson Street “for the treatment of chronic diseases of women and children” (see accompanying advertisement.) This “medical and hygienic institute” embraced all sorts of new-fangled medical apparatus then in vogue, such as “electricity, medicated baths … and all other modern medical appliances used both in Europe and America.”

Two years later, in 1875, Ferguson led—“piloted,” it was said—a party of local women on a Grand Tour of Europe. Their stops included France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland. Upon her return to Bloomington, Ferguson learned that her husband William was readying their move to Utah, as he had evidently become enamored with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (popularly known as the Mormon Church.)

After arriving in Utah Territory, the Fergusons were baptized as Latter-day Saints in the Mormon settlement of St. George. By all accounts, Ellen Ferguson embraced the Mormon faith, and devoted her early efforts in the territory to music education, becoming the cofounder of the Utah Conservatory of Music.

William died in Salt Lake City in 1880. By the following summer, when Ferguson embarked on a lecture tour on behalf of the Church of Latter-day Saints, The Pantagraph found occasion to cruelly ridicule her personal appearance and faith, describing her as “rather slovenly in attire, and unattractive.” Clearly, for some of Ferguson’s former allies, her embrace of Mormonism invited such callous criticism, irrespective of her past or present views on women’s rights.

Around this same time, Ferguson relocated to the East Coast to complete her medical education “in certain special departments, such as gynecology, obstetrics, minor surgery, etc.” She then returned to Utah to work toward the establishment Deseret Hospital (now LDS Hospital) in Salt Lake City.

In Utah, women’s suffrage was first granted by the territorial legislature in 1870. Generally speaking, Mormon women who lived in Utah (and thus enjoyed the right to vote well before most other American women) backed the goals of the national suffrage movement. Yet national suffrage leaders and activists were torn over the issue of whether to welcome support by these Latter-day Saints and, by extension, be tainted with the faith’s polygamy

In the spring of 1886, Ferguson helped lead a “Mormon women’s protest” delegation that traveled to Washington, D.C. for an audience with President Grover Cleveland. These Mormon women were there to oppose the strong-armed tactics of federal officials who were cracking down on polygamy by threatening to undo women’s suffrage in Utah (And indeed, in 1887 Congress revoked the right of women to vote in the territory, though suffrage would be restored in the first state constitution of 1896.)

Active in Democratic Party politics, Ferguson served as an alternative delegate representing Utah at the 1896 national convention, where she supported the nomination of populist firebrand and free-silver advocate William Jennings Bryan. As such, she’s sometimes cited as the first female delegate to a major party’s nominating convention.

One year later, in 1897, Ferguson severed tied to the LDS Church and sometime afterward moved to New York, accompanied by her two daughters, Ethel and Claire. The restless Ferguson then embraced theosophy, an esoteric religious movement characterized for its “mystical and occultist” underpinnings.

Ferguson passed away on March 15, 1920, at her residence in Beechhurst, Queens, New York. Her obituary in The Brooklyn Eagle newspaper called her a writer, lecturer and musician of distinction, as well as a devoted suffragist who “figured prominently in politics.”

Sadly, Ferguson did not live to see a woman’s right to vote enshrined in the U.S. Constitution. On Aug. 26, 1920, five and a half months after her death, U.S. Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby signed into law the Nineteenth Amendment granting women, at long last, the right to suffrage.