Faced with the enormity of the Second World War, it’s often difficult to put a human face on the horror. “One death is a tragedy, a million deaths a statistic,” is a chilling observation attributed to Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin.

More than 330 McLean County residents lost their lives in the global struggle between the Allied and Axis powers. You can see their names on the McLean County World War II “Four Freedoms” Memorial on the east side of the McLean County Museum of History square.

One name you’ll find is David F. McCorkle, an 18-year-old U.S. Army private killed in the Philippines on March 13, 1945. Now, thanks to a recently donated letter to the history museum, we have a story far richer than one simply fathomed from a name etched onto granite.

The letter in question was written by Julia Scott Vrooman of Bloomington to Frank and Nelle McCorkle, the grieving parents of the fallen serviceman. The McCorkles farmed 160 acres for the Vroomans in the southeast corner of Bellflower Township, where McLean County meets Piatt and Champaign counties. The farm was located south of unincorporated Osman, a grain elevator station on the Wabash Railroad.

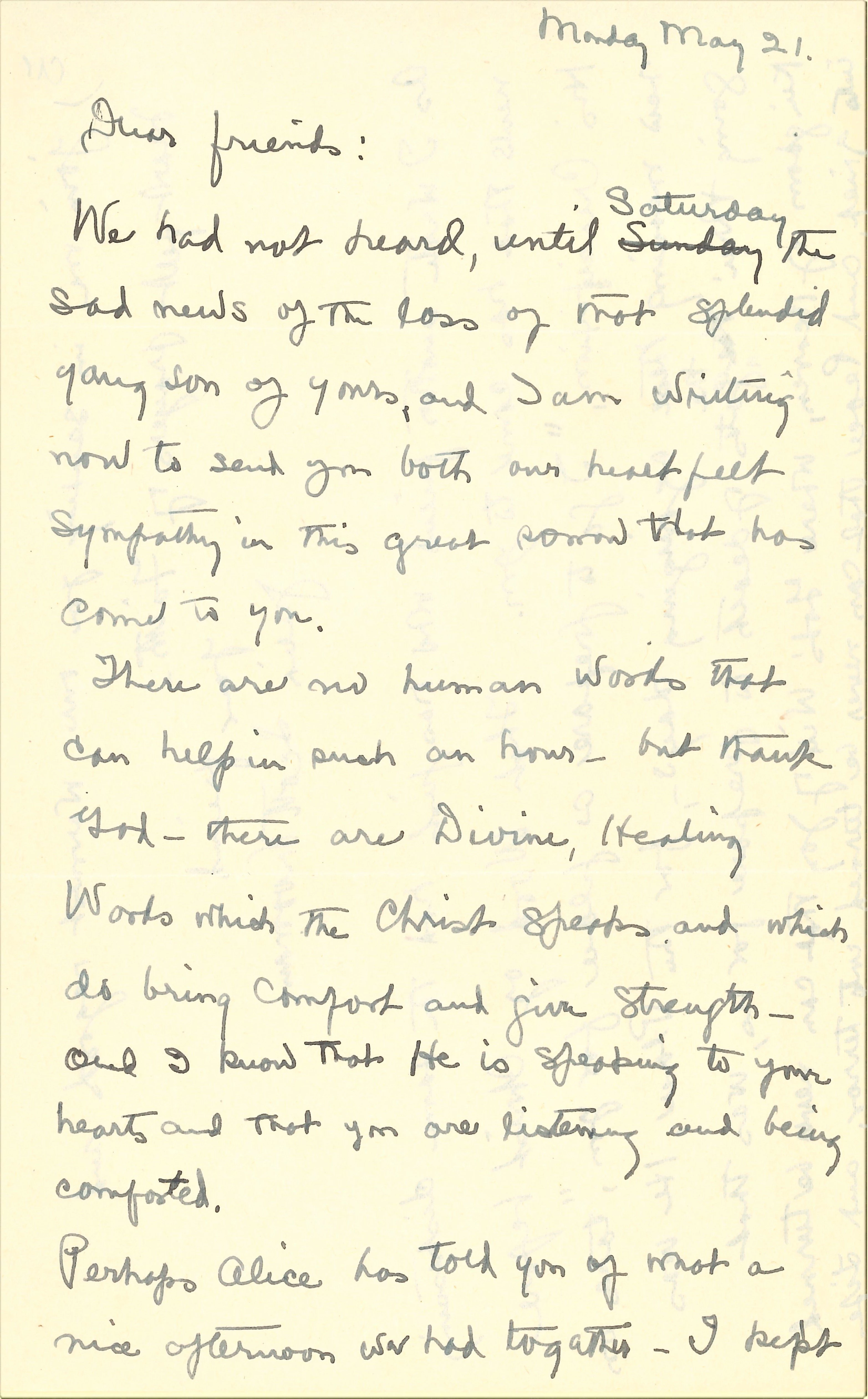

“We had not heard, until Saturday the sad news of the loss of that splendid young son of yours,” Vrooman begins her Monday, May 21, 1945, letter, “and I am writing now to send you both our heartfelt sympathy in this great sorrow that has come to you.”

Julia Vrooman was daughter of Matthew T. Scott, a wealthy McLean County landowner who first settled in Chenoa, turning thousands of acres of open prairie into tenant farms. Julia lived a privileged life of the Corn Belt aristocracy. She met her husband Carl Vrooman of Kansas on a “Grand Tour” of Europe—with the marriage proposal said to have come during a moonlight excursion on a Venice gondola.

In 1900, Julia and Carl Vrooman settled at 701 E. Taylor St. in Bloomington (now the Vrooman Mansion bed and breakfast), where Julia’s parents had lived since 1872. Carl managed the family’s tenant farms, and his interest in progressive agriculture and Democratic Party politics led to an exciting few years in the U.S. Department of Agriculture during the First World War. It was at the end of that war that Julia Vrooman found herself touring U.S. Army camps in defeated Germany, boosting the morale of weary doughboys with her ragtag, ragtime jazz band.

Two and a half decades later and another world war, one finds the Vroomans converting the third floor of their East Taylor Street home into apartments for soldiers stationed and training in Bloomington-Normal.

When Julia Vrooman learned of David McCorkle’s death, she reached out to David’s sister Alice, who was attending Illinois State Normal University. “Perhaps Alice has told you of what a nice afternoon we had together,” related Vrooman in her letter to Alice’s parents. “I kept telephoning to her landlady Saturday, hoping Alice would be back in time to go to Chenoa with us. And sure enough Alice did get back and called me up. So she and her friend and another friend of mine went with us and we had a lovely ride and our first sunny afternoon in weeks.”

The letter embodies Vrooman’s generous and high-spirited nature. “It was so nice getting acquainted with Alice,” she added. “I would know she was her mother’s daughter, if I met her in Europe! As she looks so much like Mrs. McCorkle. She is a fine girl and is making a fine record at school.”

Indeed, Alice McCorkle graduated from ISNU and went on to a teaching career, putting in 4 years at Saybook, and another 20 years at DeLand-Weldon. She married farmer Robert Floyd in 1950, and it was one of their daughters, area resident Leta Buhrmann, who donated Julia Vrooman’s letter to the McLean County Museum of History.

The McCorkle family has long cherished the letter, but Leta thought it time to find a safe and permanent home for it. The letter will be cataloged and housed in the museum’s climate-controlled archives, where it will be made available to family members, genealogists, students, researchers, community residents, and others for years to come.

Julia Vrooman’s letter also gives us the opportunity to reflect on the life of 18-year-old Pvt. David McCorkle. He attended grade school in Osman and then high school in Bellflower, where he graduated in 1944. He joined the U.S. Army shortly after graduation, receiving his basic training at Camp Croft in South Carolina. He was overseas by December—if not earlier—and dead three months later.

A week or so after Vrooman wrote her letter, the McCorkles received their son’s posthumously awarded Purple Heart. Nelle McCorkle also accepted a letter from her son’s company commander detailing David’s death. “He was killed by an enemy 91 mm mortar shell while on a reconnaissance patrol with his squad,” it read in part. “Death was instant.” McCorkle was interred at the U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) Cemetery No. 1 in Zamboanga City, Philippines.

In the years following World War II, the remains of tens of thousands of American war dead returned stateside for reburial in hometown cemeteries. Pvt. McCorkle’s earthly remains arrived at Stensels Funeral Home in Bellflower on Sept. 1, 1948. Two days later, funeral services were held at the Osman Methodist Church, with the Rev. S.N. Madden officiating. David McCorkle was laid to rest one last time at Blue Ridge Cemetery, not far from Osman.

Julie Vrooman’s condolence letter is also a testament to the power of one’s faith. In it, she assures Frank and Nelle McCorkle that the Kingdom of Heaven is a place “where God’s will of joy can never be turned into grief, and peace can never be turned into terror, and life can never be turned into death.”