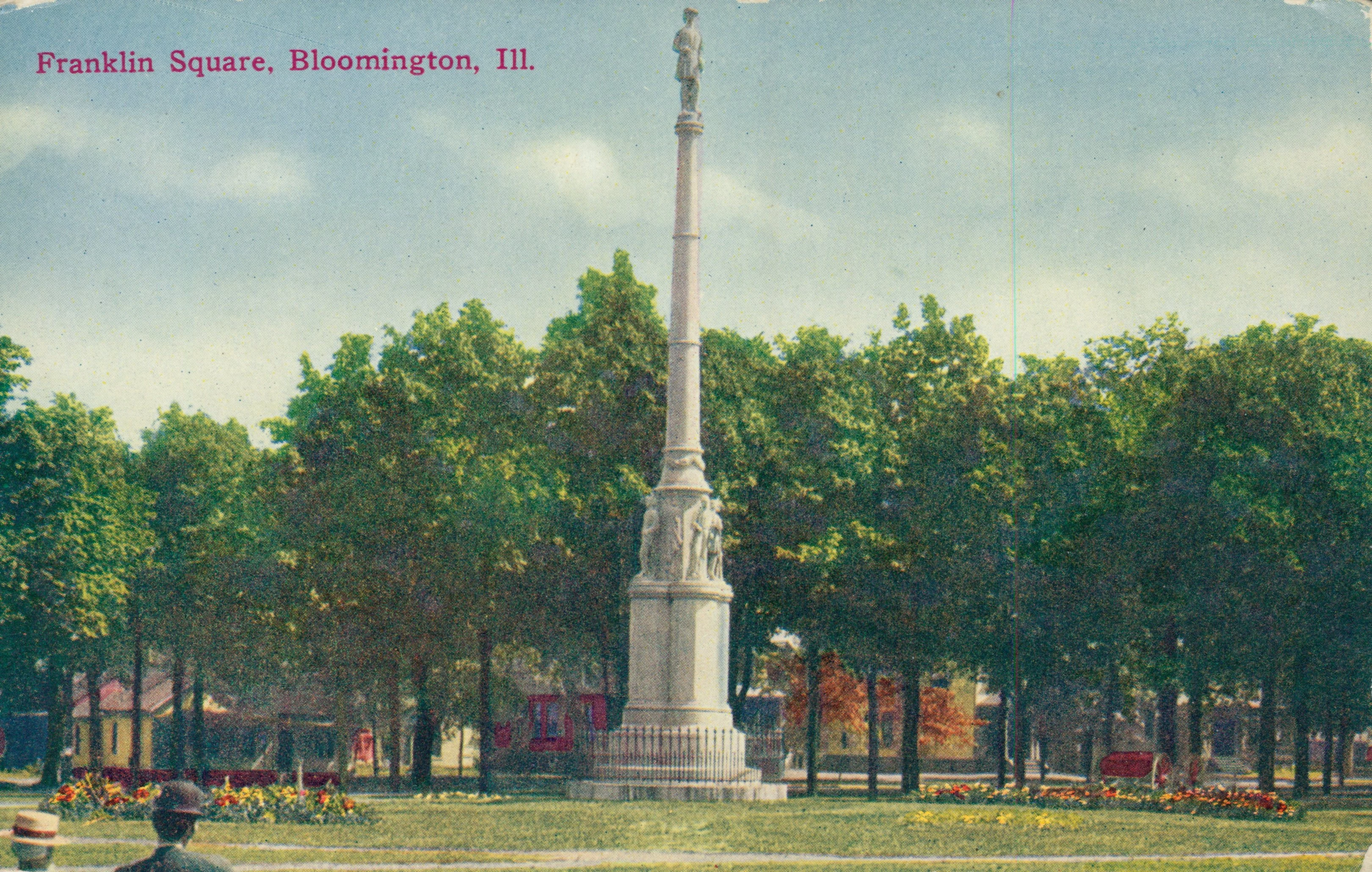

On June 17, 1869—150 years ago this week—area residents packed Bloomington’s Franklin Park to dedicate a monument to the more than 700 McLean County men who made the ultimate sacrifice in the Civil War.

Unfortunately, the inferior quality of the monument’s marble and limestone was no match for the Midwestern climate, and the steady deterioration led to its razing a short 45 years later—in 1914.

Back in 1866, one year after the end of the Civil War, McLean County voters gave the board of supervisors (the predecessor to the county board) authority to issue bonds for the construction of a soldiers’ monument. James S. Haldeman, a Bloomington dealer in marble, limestone and granite, received the contract to design and build the memorial. Its price tag was an astounding $15,000, the equivalent to a quarter million dollars today, adjusted for inflation.

Haldeman’s design featured a lower base of Lemont limestone comprised of four octagonal columns. Upon these columns the names of the more than 700 war dead were inscribed, listed by unit and company. Above the columns were martial figures representing the infantry, cavalry, navy and a Zouave soldier (the latter a nod to regiments that adopted North African–inspired uniforms popular back then.) Above the marble figures were the words, “McLean County’s Honored Sons, Fallen but Not Forgotten.”

Towering over that assemblage was an 18-foot-high tapered shaft, itself topped by a fifth figure, a colonel looking southward, his right hand holding field glasses and his left resting on the hilt of a sword. The monument reached 49 feet, from the ground “to the top of the colonel’s head.”

Dedication ceremonies were held June 17, 1869, and began with a procession from downtown Bloomington to Franklin Park. “The Temple of Honor, the Odd Fellows, the German Benevolent Society, the Hibernian Society, the Turners, the fire [department] companies, all in their respective regalia and emblems, made a splendid display,” noted The Pantagraph.

Once at Franklin Park, John L. Routt, the McLean County treasurer, called the “immense gathering” to order (in seven years time, Routt would become the first governor of the newly established state of Colorado.) Kadel’s Cornet Band provided the music, and Dr. A.E. Stewart, surgeon in the 94th Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry during the war, recited an appropriately patriotic and maudlin poem written for the occasion. Bloomington attorney Lawrence Weldon, who traveled the Eighth Judicial Circuit with Abraham Lincoln, delivered the dedicatory address.

Yet the poor quality of the marble meant the monument’s carved figures, exposed as they were to Central Illinois weather, never had a fighting chance. In the spring of 1898, the artillery figure on the monument’s north side “fell to the ground with a frightful crash and was ‘shivered’ into small pieces.” A crowd soon gathered at the scene, with more than a few gawkers noting that the broken-up figure lay directly under word “Fallen” in the main inscription. “The marble,” observed The Pantagraph, “crumbled in the hand like sugar.”

In March 1910, a second figure, this one of the south side, came crashing down. “The marble from which the figure was hewn, though originally hard and flinty, has disintegrated under the influence of the weather until it crumbles in the hand like salt, and as easily,” noted The Daily Bulletin, another Bloomington newspaper of the day.

“At present it is a menace to passerby,” The Pantagraph said one month later of the monument, “and it is rapidly going to destruction.” The limestone facing was also failing, for by this time most of the names inscribed on the columns were weathered to the point of illegibility.

The monument’s sad condition spurred elected officials, area veterans and community leaders to commit to the erection of a new one at Miller Park on Bloomington’s west side. Dedicated Memorial Day, May 30, 1913, the 78-foot tall McLean County Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument features eight bronze tablets with the names of more than 6,000 individuals who fought in wars spanning the American Revolution to the Spanish-American War.

In late Oct. 1914, county and city officials jointly agreed to raze the Franklin Park monument. It came down two months later, a few days before Christmas Day 1914, with a heavy snowfall necessitating the pieces be carted off on sleds.

The razed monument—“or any part thereof”—was then put up for public sale. “As much of the stone as possible is being sold to local people, who desire it in ornamenting door yards,” announced The Pantagraph. One wonders, then, how many of these relics can still be found resting on local lawns!

At an undetermined time, the intact lower base, with its four worn-and-weathered limestone columns, was moved to an area northeast of the corner of Linden and Emerson streets, in what’s now the Briarwood neighborhood straddling Bloomington and Normal.

Today, parts or all of several dozen names inscribed on this imposing, picturesque remnant are still legible. Those names include Pvt. Joseph Means, a farmer from Cheney’s Grove in eastern McLean County, who died June 29, 1863 at a camp hospital at Young’s Point, La. Means was a private in Co. F of the 116th Illinois Infantry Regiment, which included more than 80 McLean County men, all but a few of them from Cheney’s Grove.

Organized in Decatur in the fall of 1862, the 116th participated in some of the bloodiest battles and campaigns of the war, including Vicksburg, Chattanooga and Missionary Ridge, Atlanta, and Sherman’s March to the Sea. Of the company’s 83 members, 26 were killed or died in the war, a fatality rate of 31 percent.

Means, who was two weeks shy of his 33rd birthday when he enlisted, was married to Matilda Rankin. The couple had at least five children when Joseph marched off to war. The youngest, Marcus, was one-and-a-half years old at the time of his father’s death. Pvt. Means’ earthly remains were returned to McLean County, and he was laid to rest at Cheney’s Grove Township Cemetery.

“May the sword be beaten into a plowshare and the spear into a pruning hook,” Lawrence Weldon said at the dedication of the Franklin Park soldiers’ monument 150 years ago this week, “and may our children dedicate monuments to the victories of peace, rather than the triumphs of war.”