Working the Land

Working the Land

Frontier farmers relied on animal labor and hand tools. Then the railroad brought an influx of immigrants willing to work. In the 20th century, the number of farms and farmers in McLean County decreased, while the number of acres in a farm continued to rise.

1822 to 1852

Frontier farmers were faced with the challenge of producing enough livestock and crops to support their survival using only animal labor and hand tools. Before they could plant, they had to break the land.

1853 to 1899: Labor

The railroad arrived in 1853, bringing with it an influx of immigrants willing to provide labor on McLean County’s growing farms.

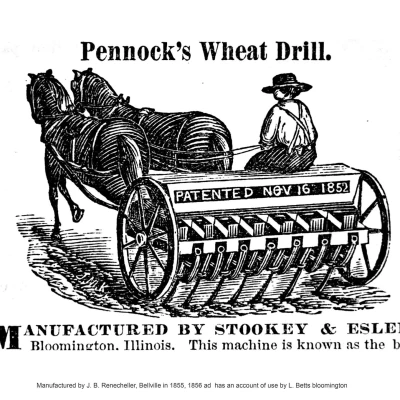

1853 to 1899: Diversified Farming

From 1850 to 1900, the typical McLean County farmer made a living as a diversified farmer, growing a rotation of corn, wheat, oats, and hay which was stored on the farm and then fed to the cattle and hogs that were raised for market. Advances in the plowing, planting, cultivating, and harvesting of crops meant more acres could be farmed with less labor.

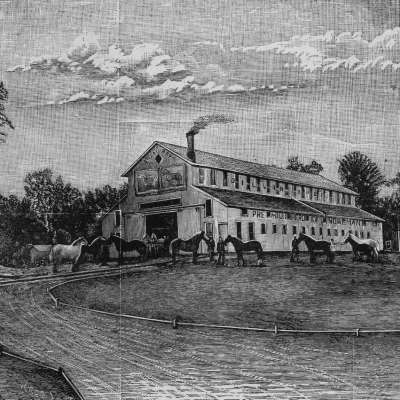

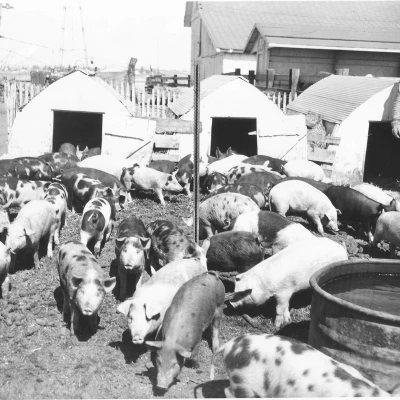

1853 to 1899: Feeding and Breeding Livestock

As McLean County farms grew in size, so too did the farmers' ability to raise livestock for market. Those with the capital to invest in high quality breeding stock earned the highest profits. These were typically the successful livestock feeders.

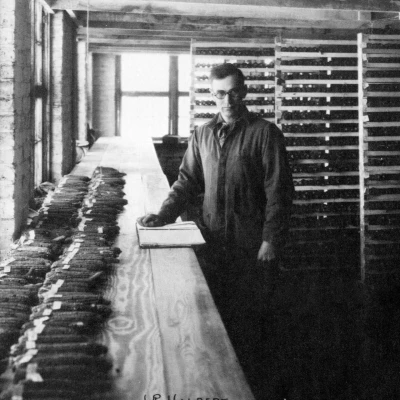

A Scientific Revolution: Eugene Funk and Hybrid Corn

In 1883 McLean County farmer and entrepreneur Eugene D. Funk began to develop a modern system of hybridization. In 1915 he hired Dr. J. R. Holbert, whose inspired research quickly achieved Funk’s goal to produce high-yielding commercial hybrids. Funk continued to develop improved hybrids that dramatically increased corn production in McLean County and around the world. The Great Corn Belt exists today because of Funk’s scientific and visionary approach to producing high quality seed corn.

1900 to 1945

Labor shortages during WWI and II, the Great Depression, improved equipment, and the shift of many farmers away from the farm dramatically impacted farming in the early 20th century.

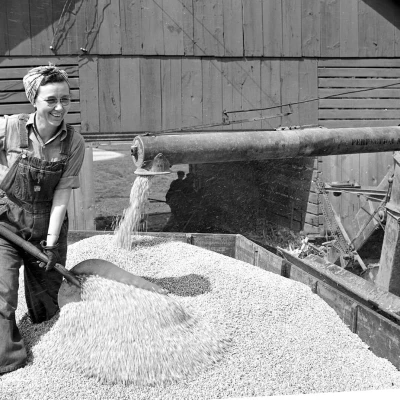

1900 to 1945: Livestock

From 1900 until the end of WWII, McLean County farmers continued to raise a diverse variety of livestock.

1900 to 1945: Tenants and Labor

The purchase of mechanized tools, like tractors and harvesters, increased equipment costs for the tenant farmer. But if he managed the farm well, the costs of labor and maintenance of animal power were reduced enough to balance out the cost of the machinery and increase his profits.

1946 to 2000: Larger Farms

After World War II the number of farms and farmers in McLean County slowly decreased. At the same time, the number of acres in a farm continued to rise. Larger farms required bigger, more complex equipment in order to get the job done. But not all farmers—or their children—had the capital or the desire to continue farming given the financial risks.

1946 to 2000: Corn and Soybean Crops

After WWII many McLean County farmers reduced or totally eliminated livestock production in order to focus on more profitable corn and soybean crops. As larger, more advanced technology became available, farmers were able to finish planting their crops in the seven to ten days of good weather typically available each spring.

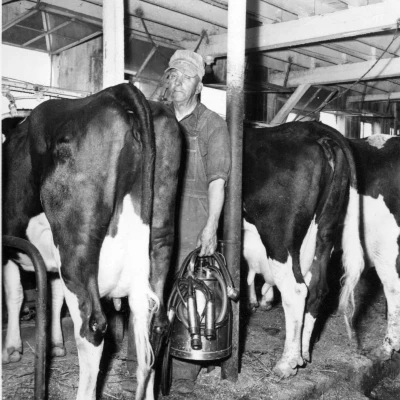

1946 to 2000: Livestock Consolidation

After WWII profits for those raising livestock began to decrease. As a result, so too did the number of livestock farmers. Those who continued to raise livestock had to adopt new management techniques if they were to be successful. To offset smaller profit margins, they invested in equipment and buildings that reduced land and operation costs, and increased production efficiency through controlled environmental conditions.

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County