Working the Land – 1900 to 1945: Livestock

“Every farm had milk cows, beef cattle, pigs, chickens, and maybe some sheep. . . If you were old enough to walk, you were old enough to work. I think my first job was taking care of a flock of chickens. I remember driving a tractor at the unbelievable age of maybe 5 or 6 years old—supervised, of course.”

— Frank Wieting, July, 2015

For many McLean County farmers, the breeding and feeding of livestock for market was big business.

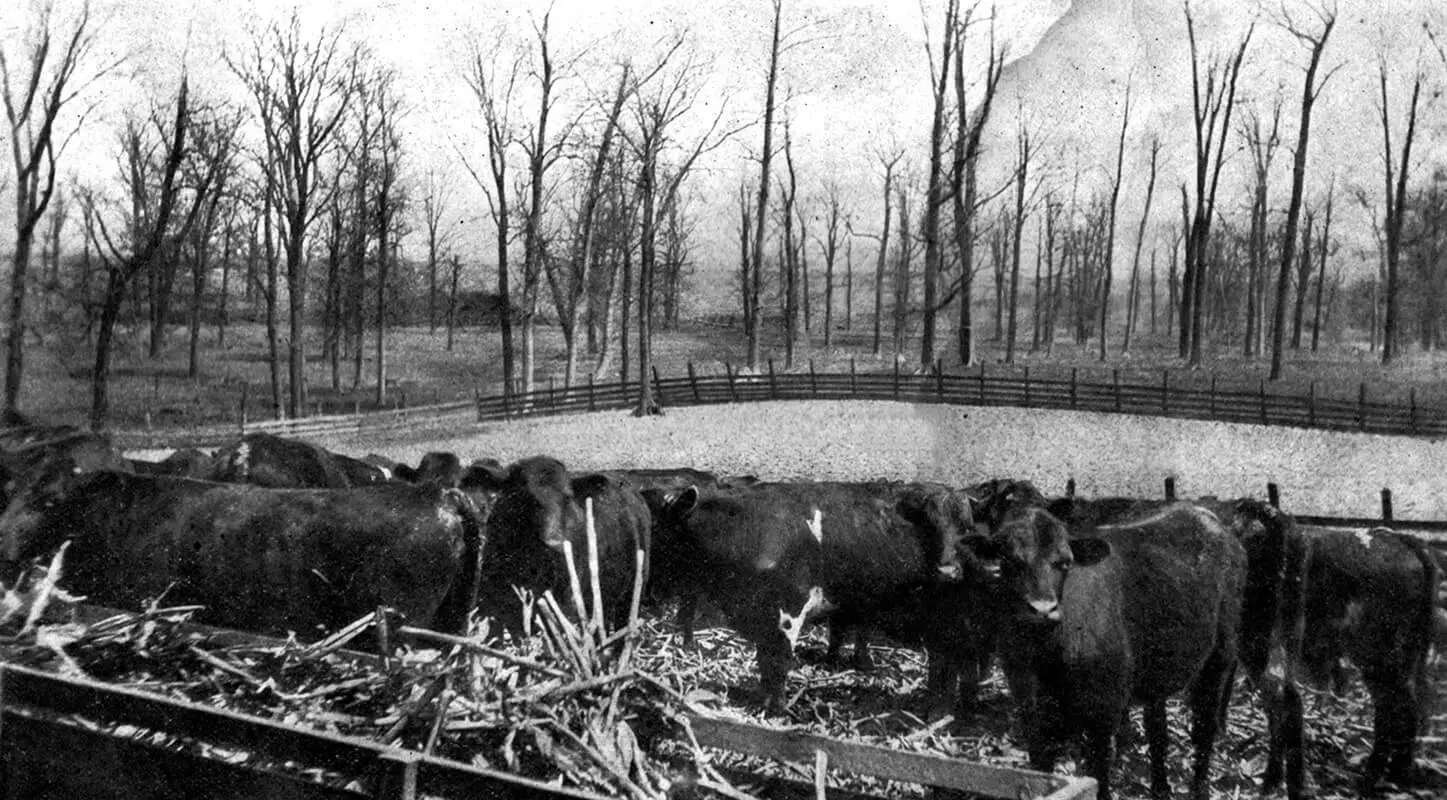

Profitable cattle feeding was a lifetime practice on the Price N. Jones farm near Towanda. Jones rented his farm to his son Len and grandson H. Carey Jones, so he could focus his efforts on feeding 250 cattle every year.

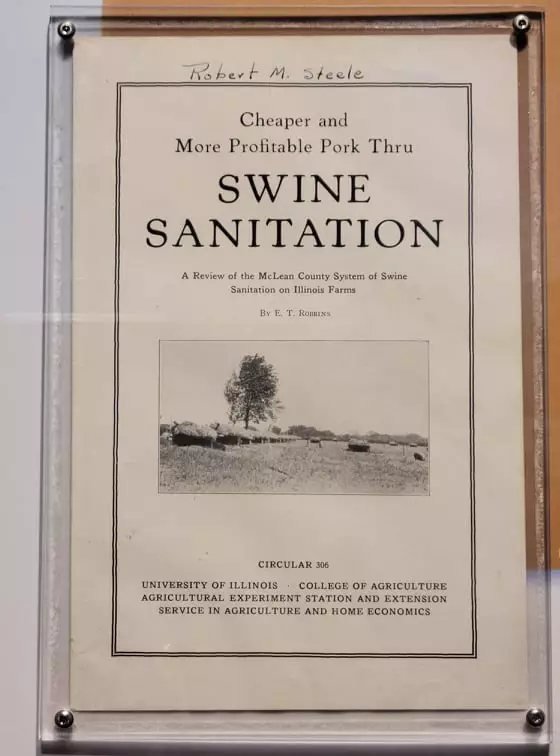

McLean County hog farmer Lyle Johnstone paved the way for winning the long running battle against deadly roundworms and filth-borne disease.

In the fall of 1919 the University of Illinois partnered with Johnstone to test the McLean County System of Hog Sanitation. It challenged old ideas about how hogs should be housed — required a clean and sanitary environment for them.

Johnstone’s system required sows to be thoroughly cleaned and the pens sanitized before farrowing (birthing baby pigs). After the pigs were born, the sows and their litters were hauled, not driven, to clean pastures. In the pasture a moveable house was available for each sow and litter that could be relocated when the ground became dirty. The system was not new. In fact, it was very similar to the one used by Arthur Funk as early as 1913.

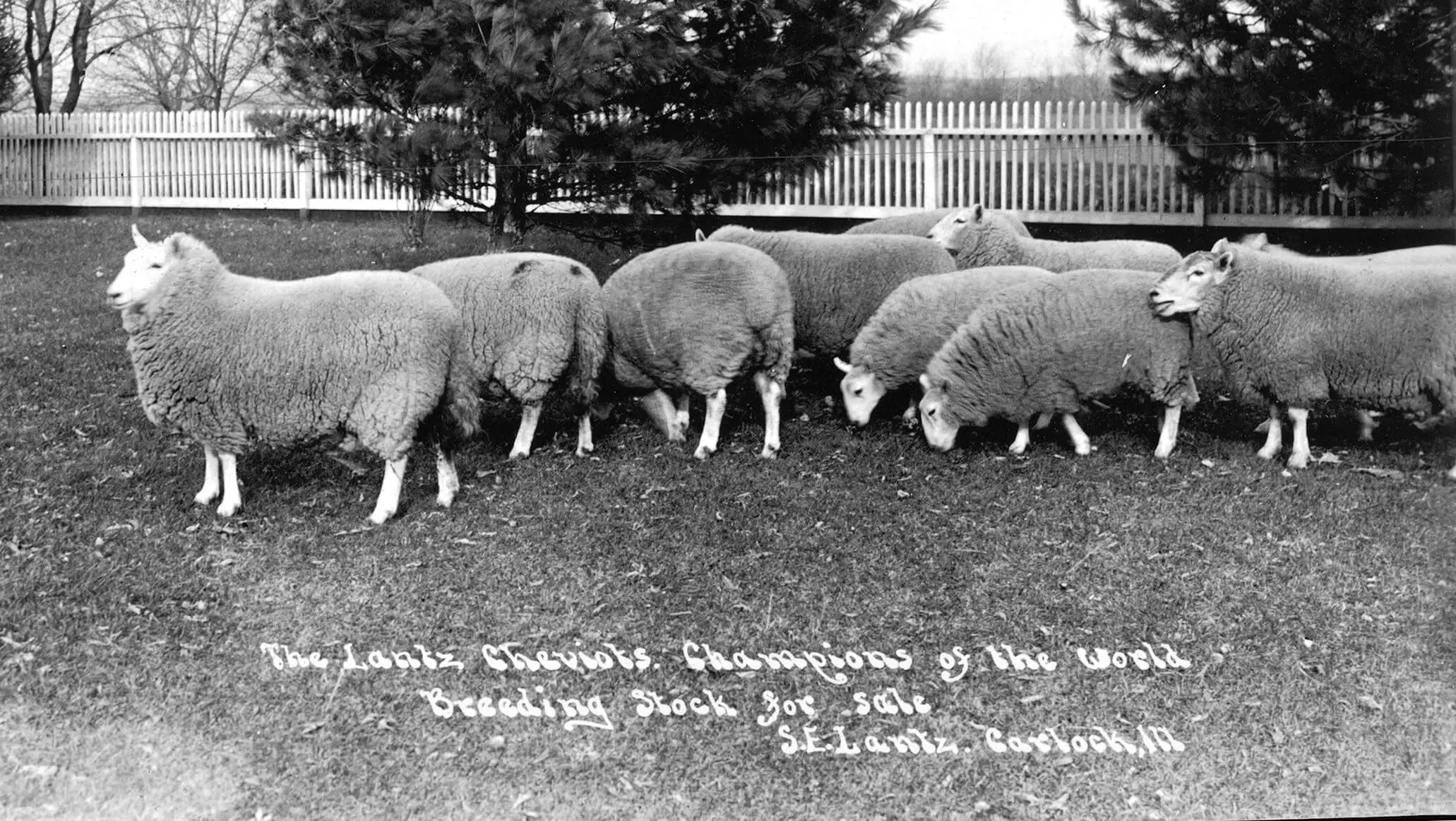

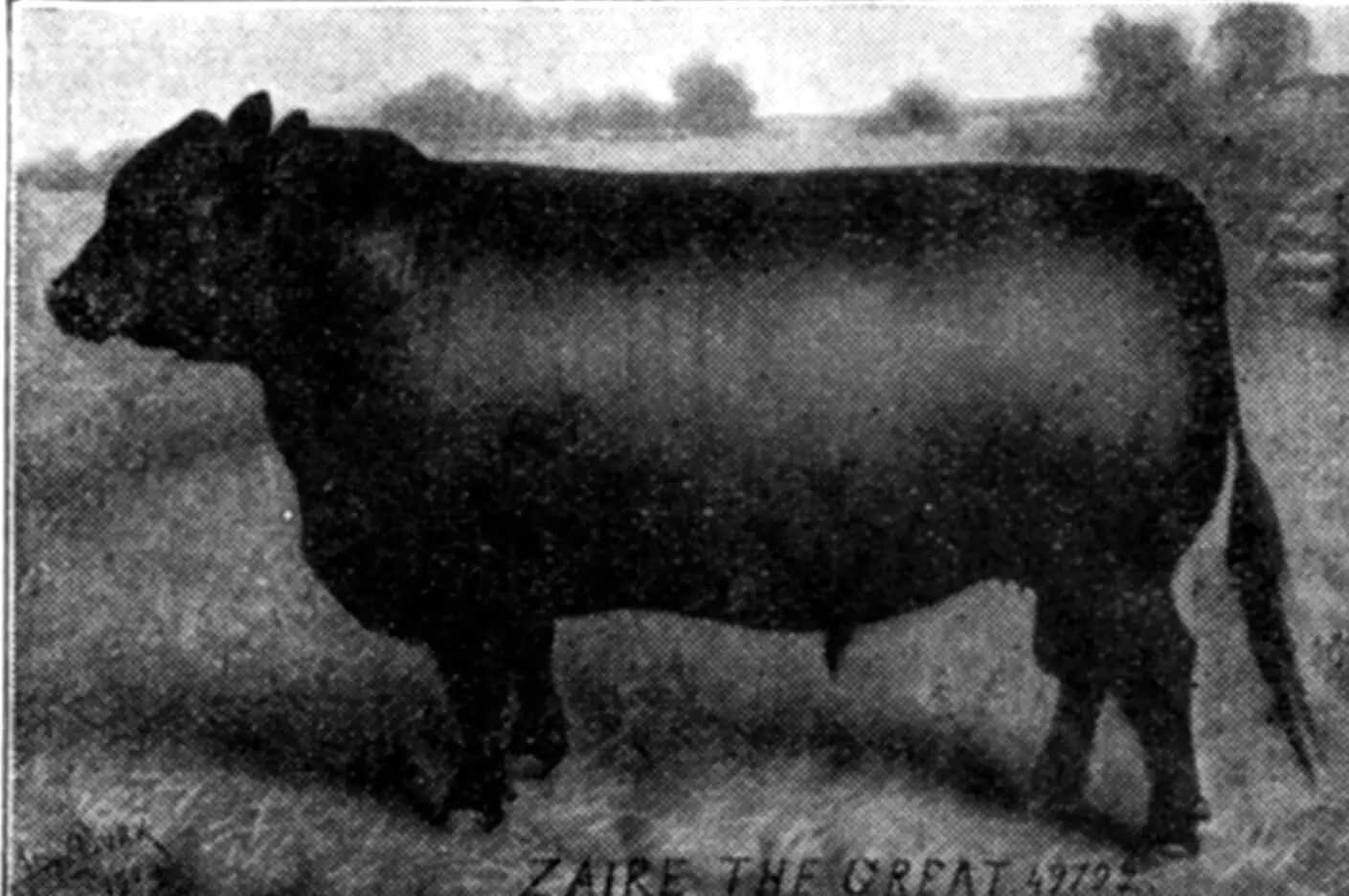

Carlock area farmer Milo Lantz had great success as a breeder of both Cheviot sheep and Angus beef.

Lantz’s Aberdeen Angus bull, “Zaire the Great,” earned first place at the International Livestock Fair in Chicago in 1905. The award increased the value of his herd of Angus cattle sired by Zaire.

As silage cutting equipment improved, more McLean County farmers fed silage to their livestock and more built storage silos.

“The cost of handling the corn crop in the form of silage cost less than other methods.” And, according to Bloomington Pantagraph sources in 1909, “corn silage is much more palatable to livestock than corn shocks.”

By 1913 LeRoy farmer J.V. Smith had built a 100 ton brick silage silo. Right next to the barn, it made feeding his 45 head of cattle much easier. Smith’s herd ate about 35 bushels of silage per day.

In June of 1917 the Pantagraph reported that area farmers had purchased 53 wood and tile silos from Bloomington’s Illinois Silo and Tractor Company the previous month. Wooden silos were especially popular as they were less expensive to build. But these structures did not last as long as tile and cements silos.

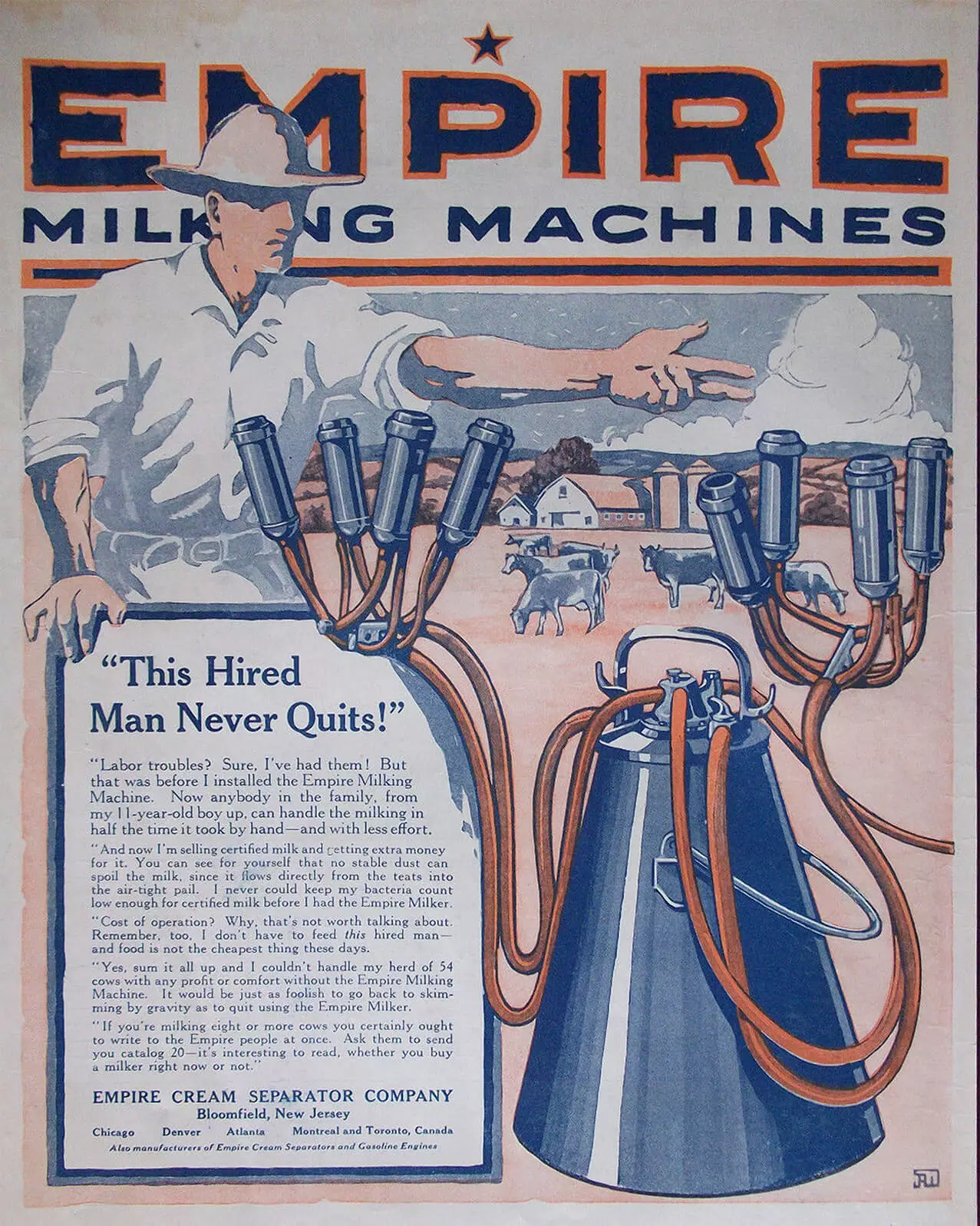

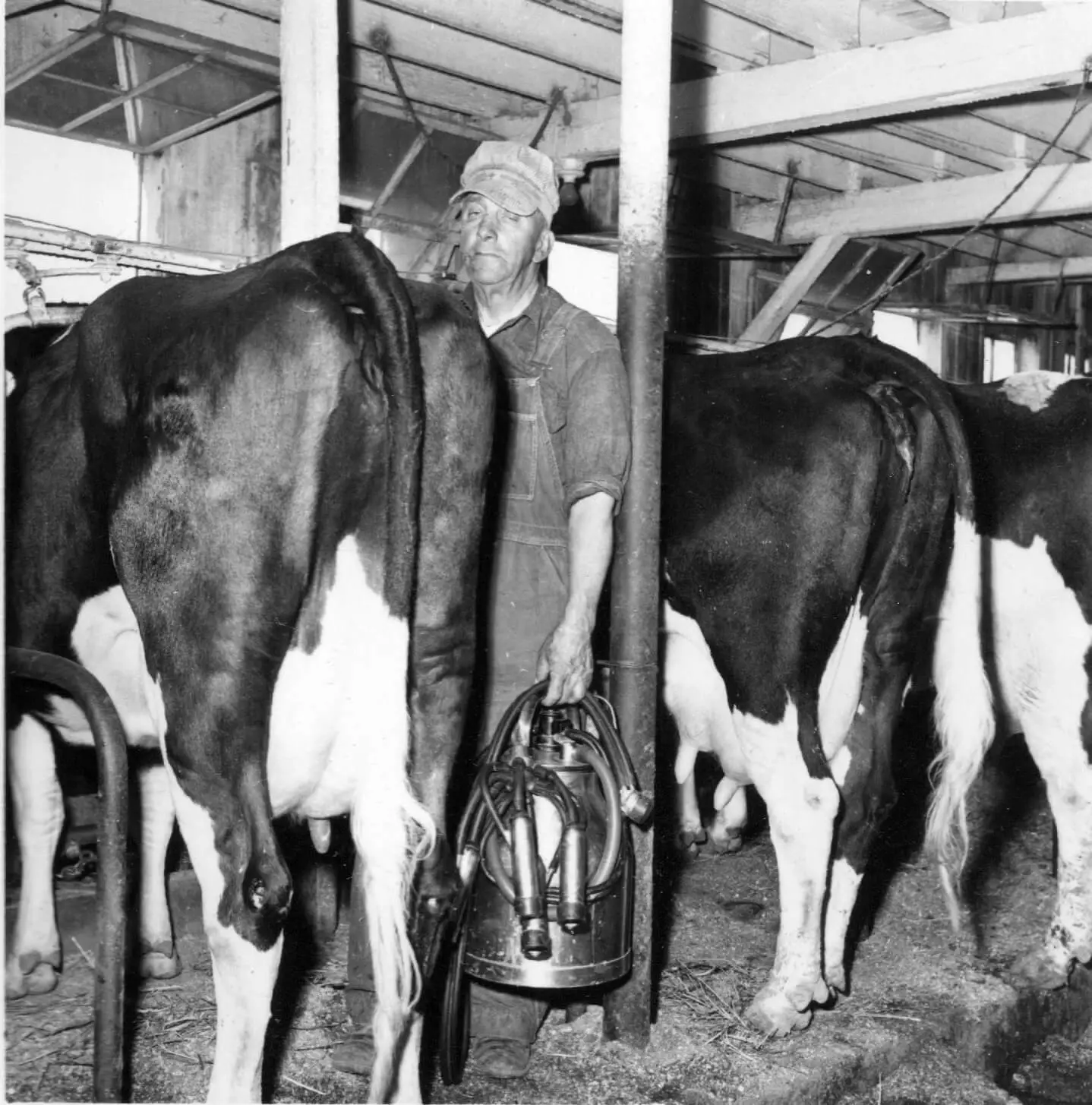

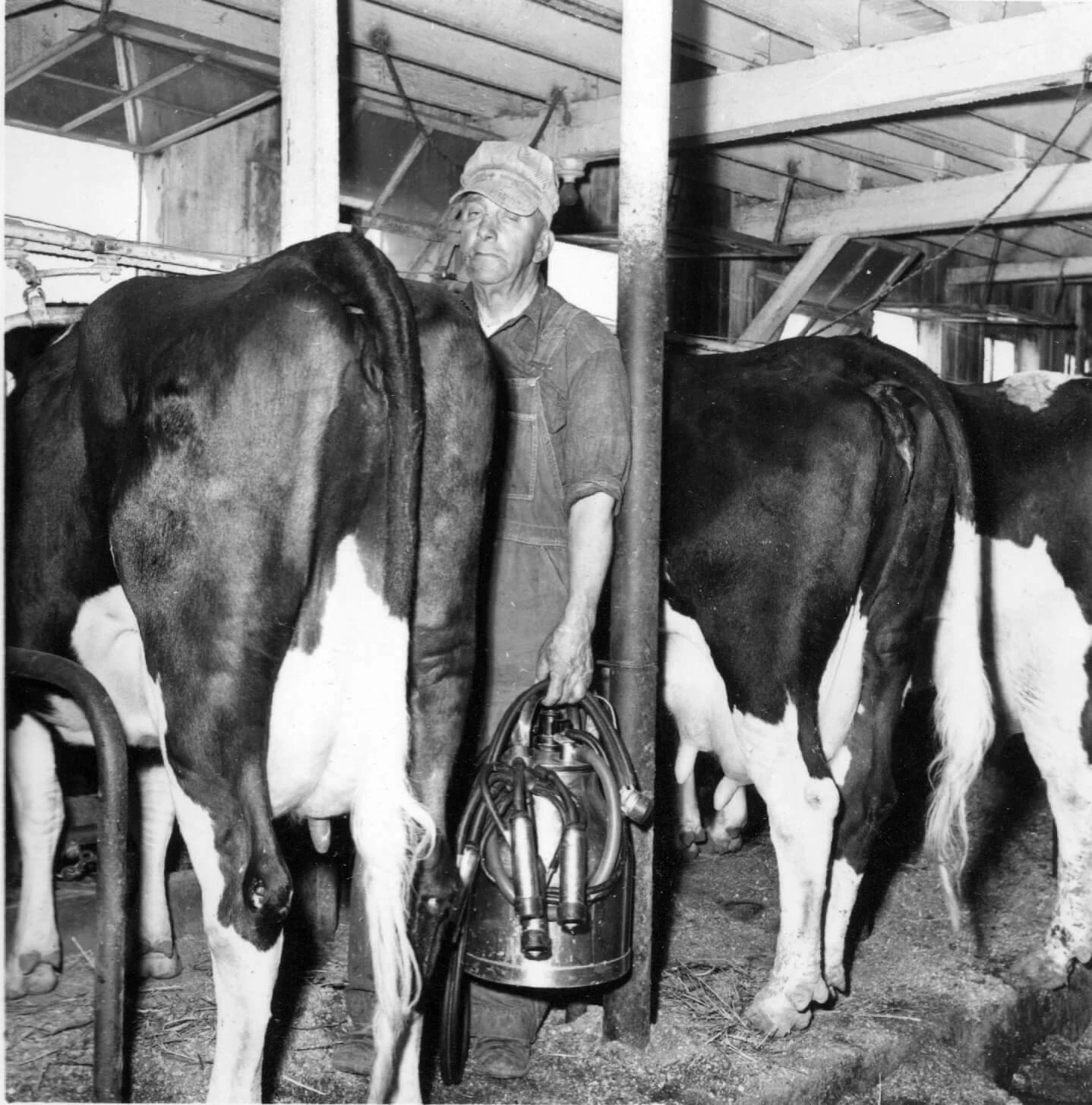

Dairy farmers who kept pace with recent research and new technology, and who managed their herds well, increased their production as well as profits.

WWI labor shortages left Danvers dairyman Joe Ayres unable to hire help for milking. He purchased his first milking machine that year (1917). Ayres expected the machine to reduce the labor needed to milk his 22 cows.

The first vacuum milking machine was built in 1851, but it was 1922 before a machine that didn’t harm the cow was developed. Use of milking machines grew rapidly after 1923 when the Surge Bucket Milker was introduced.

Concerned about the quality of the milk they produced, members of the McLean County Dairy Herd Improvement Association, had their cows regularly checked for disease using a trained tester.

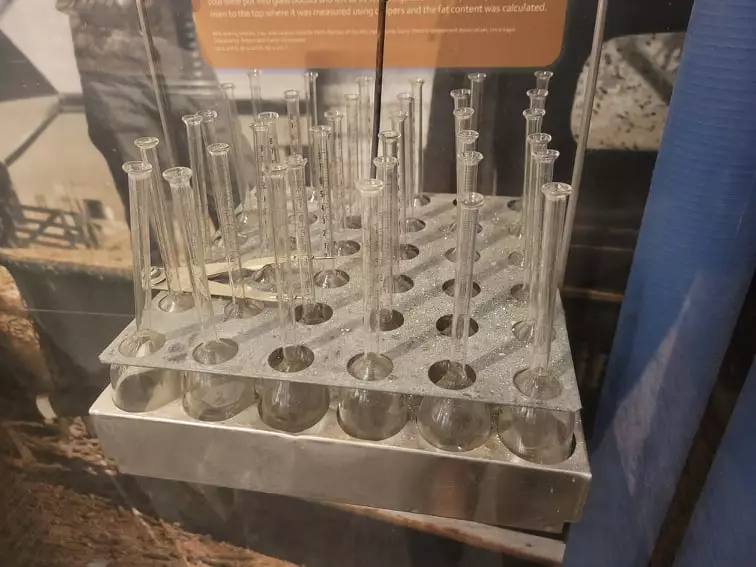

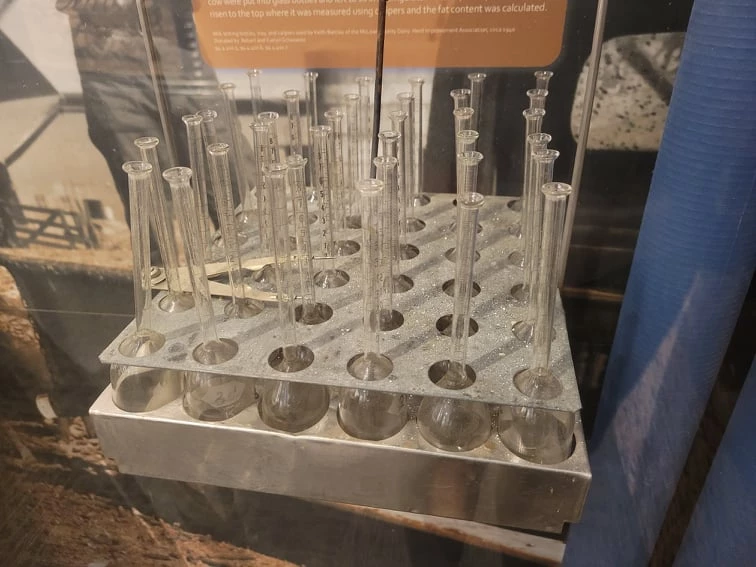

They also had their cows’ milk tested to measure fat content. Samples from each milk cow were put into glass bottles and left to sit in a refrigerator. After 24 hours, the cream had risen to the top where it was measured using calipers and the fat content was calculated.

Milk testing bottles, tray, and calipers, circa 1940

View this object in Matterport

Used by Keith Barclay of the McLean County Dairy Herd Improvement Association.

Donated by: Robert and Evelyn Schwoerer

94.4.410.5, 94.4.410.6, 94.4.410.7

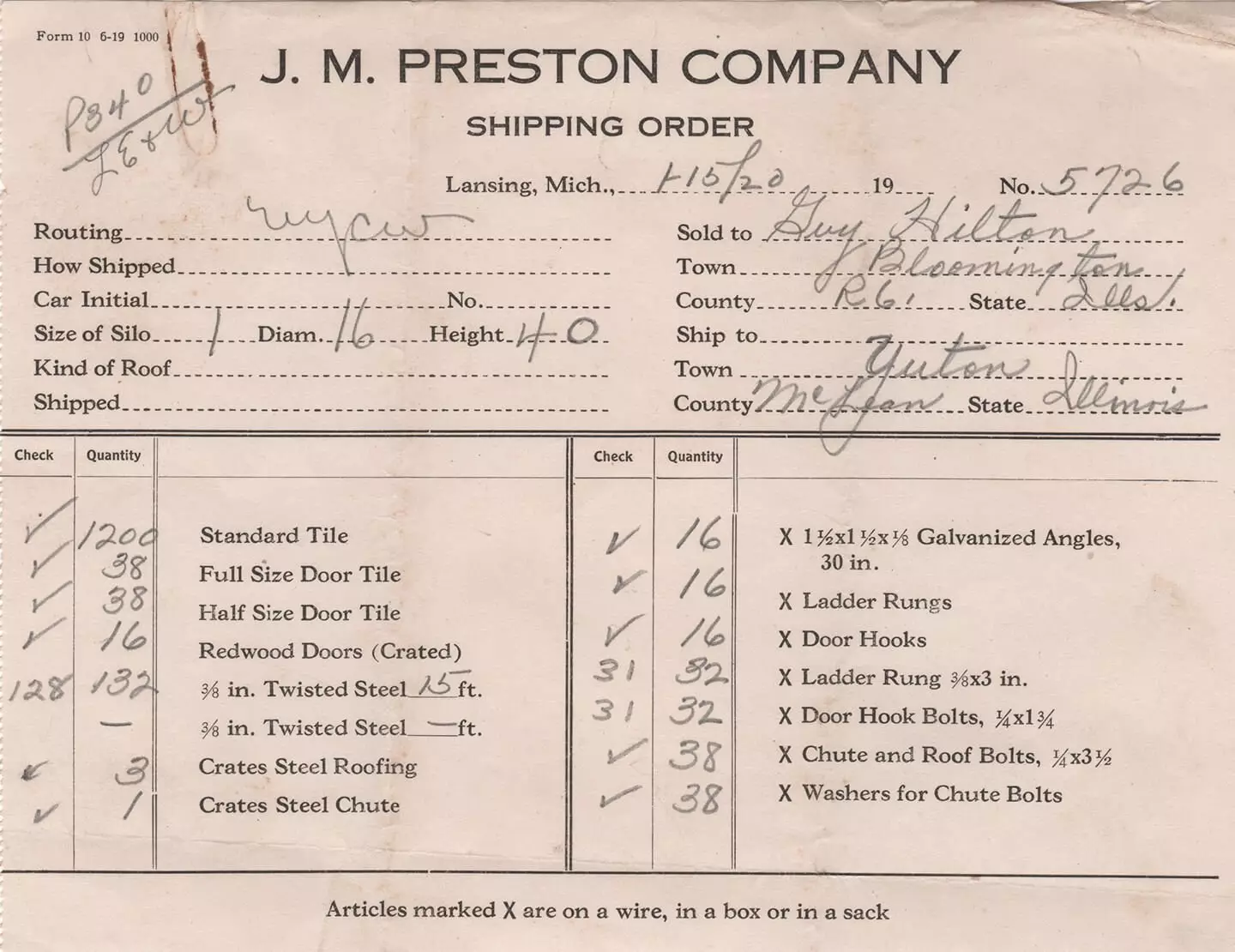

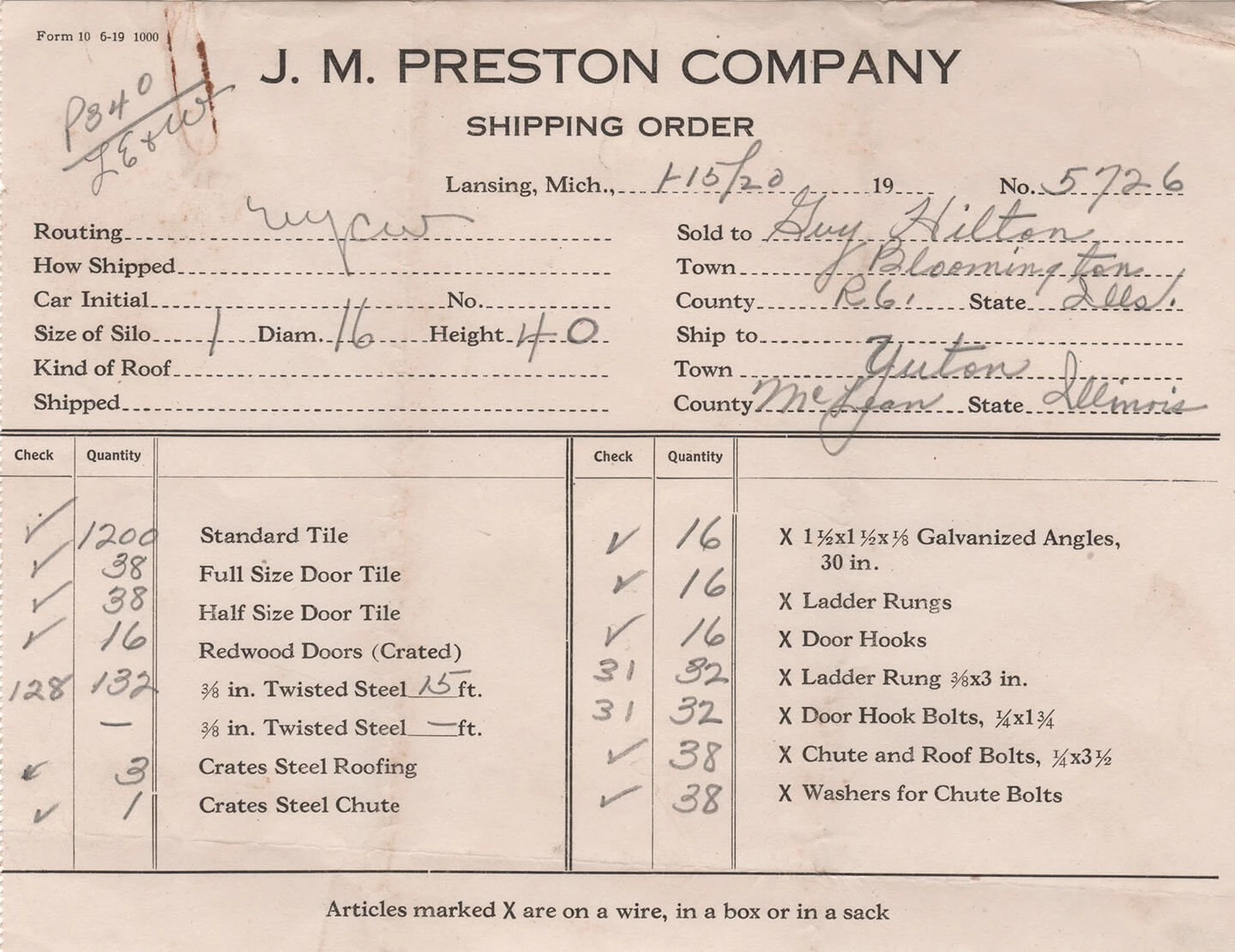

Guy Hilton, who farmed and had a dairy herd northwest of Normal, built a tile silo in 1920.

Hilton did his research first, deciding on a Preston-Lansing vitrified tile silo. He ordered the tile by mail and had it shipped to Yuton, just west of his farm.

Hilton chose not to purchase the silo roof so he could store more silage. When packed to the top he put fencing around the outside edge, then added more silage to the top of the fence. Then he added more fencing, inset a couple feet from the first fence, and then another. This enabled him to store another ton or more of silage.

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County