Working the Land – 1900 to 1945

Prior to WWI the number of tenant farmers in McLean County grew as the value of land increased and as more owners moved to town to retire or pursue a different occupation.

Like O. W. Kraft, many McLean County farm owners found that they still made good money if they rented their farm to a tenant. Some retired while other found less demanding work in town.

Kraft sold this farm in 1911 for $270 per acre.

By 1920 less than 40 percent of McLean County farms were operated by their owners.

Kraft sold all his livestock and equipment when he retired. A complete list was published in the Bloomington Pantagraph on January 16, 1909.

Kraft retired and moved to town in 1909. He rented this 160-acre farm near Towanda to Andrew Anderson. A good tenant choice, Anderson raised livestock and spread manure on his fields, which helped to maintain the nutrients in the soil. Kraft earned about $3,106 from this and another rented farm of 170 acres in 1910, and again in 1911.

During WWI and WWII, U.S. farmers faced labor shortages. At the same time the U.S. government asked them to increase production to fill growing needs at home, as well as the needs of European allies.

Despite labor shortages many showed up for annual corn husking competitions. The 1935 state championship, held south of El Paso, brought in 25,000 spectators. Though Simon Oltman (pictured to the right) came close to retaining his 1934 state husking championship title, Irvan Bauman of Congerville picked 36.5 bushels of corn to win the 1935 state championship and the $75 cash prize.

Getting the needed labor to husk the corn crops was often difficult.

McLean County farmers received draft deferments during WWII, but laborers did not. The Farm Security Administration tried to resolve the resulting shortage by transporting and training laborers from southern Illinois for placement on McLean County farms. Shortages were so bad that advertisements were placed in out-of-state newspapers.

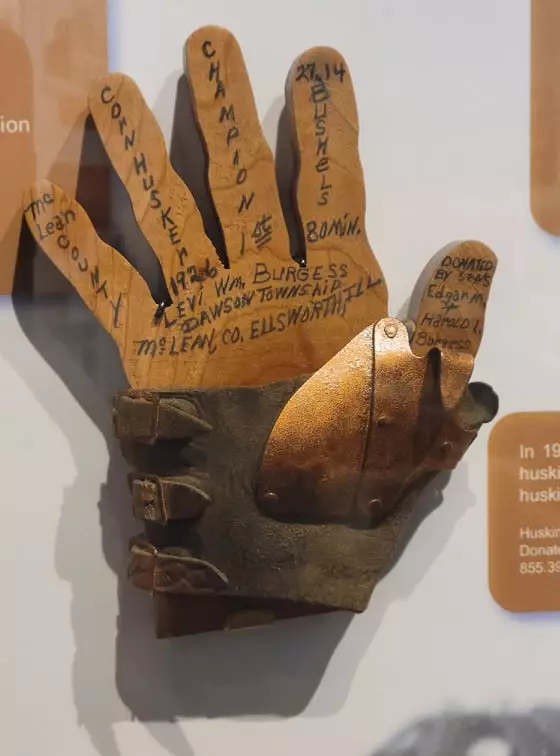

Husking Hook, circa 1926

View this object in Matterport

In 1926 Levi Burgess was the McLean County corn husking champion. He won the competition using this husking hook to pick 27 bushels of corn in 80 minutes.

Donated by: Edgar and Harold Burgess

855.392

During WWI farmers were asked to increase their production of wheat for export to war torn Europe.

The Banner brothers, Bert and Mert, who farmed 800 acres east of LeRoy, met the government challenge to grow 20 acres of wheat for every 160 acres farmed by growing 72 acres of wheat.

By WWII most of McLean County’s wheat production had shifted to Great Plains states as farmers focused on growing corn and soybeans — both more profitable and less risky.

“What are we going to do with this country if we don’t fight the war thru? . . . It is entirely reasonable to ask every farmer of 160 acres to grow 20 acres of wheat.”

— Bloomington Pantagraph, July 13, 1918

When WWI ended farmers found themselves unable to sell the surplus wheat they continued to produce. A farm depression reduced profits through the 1920s and got worse after the crash of the stock market in 1929. With the onset of the Great Depression, many found themselves unable to pay their mortgages and facing bankruptcy.

Michael Larkin used his 160 acre farm as collateral for a loan to purchase 120 additional acres of farmland. Unable to make his mortgage payments, the Money Creek township farmer lost the entire farm. A few weeks later President Roosevelt placed a moratorium on farm foreclosures, but it was too late for Larkin.

On February 3, 1930, Bloomington’s Pantagraph printed a public notice that John Kinsella was in bankruptcy. This was just one of hundreds the newspaper published during the depression of the 1930s. Some were able to resolve payment issues with their creditors while others, like Larkin, lost everything. Fortunately for Kinsella he was able to settle his debts with creditors.

Forage crops, like clover and alfalfa, for feeding both work horses and livestock, continued to be a necessary part of the crop rotation.

Wendell Beeler and his son Bill plowed under the last cutting of their clover field to return vital nitrogen to the soil. This also added fiber and organic matter to the soil, which improved fertility and the soil’s ability to resist wind and water erosion.

In 1910 alfalfa, with its feed value, excellent yields, and nitrogen value, was the most profitable forage crop.

Area farmers began to apply lime, rock phosphate, and other fertilizers to their soil. The result was greater yields for small grains, such as wheat, rye, and oats.

Corn farming was becoming more complex—tractors were beginning to replace animal labor, and there were new choices in planting and harvesting equipment.

Preparation of the soil, planting, weeding, and harvesting all happened faster with a tractor. Besides saving time, tractors reduced labor cost.

The Funks invested in a mechanical corn picker, which reduced the labor needed to get corn out of the field.

The crops raised by McLean County farmers became more diverse with the addition of an entirely new crop, soybeans. They also had the option of planting hybrid corn.

McLean County farmers learned of the value of soybeans as early as 1897. They first planted soybeans as a forage crop in 1915.

Rich in protein, soybean hay was harvested green and fed to steers, dairy cows, hogs, and horses.

Combined with corn, it provided a balanced ration for livestock. It could also be plowed under, delivering a rich source of nitrogen to the soil.

“It would pay to grow a good crop of beans for no other purpose than turning it under.”

— Bloomington Pantagraph, December 22, 1923

McLean County farmers switched from planting soybeans as a forage crop to harvesting just the seeds using a combine when the value of soy meal (made from the bean only) began to rise. By the mid-1920s Illinois had become America’s leading producer of soybeans.

Profits soared for local soybean farmers because demand was high, and they did not have to pay to ship the grain elsewhere for processing.

McLean County farmers quickly switched from drilling (planting in close rows) soybeans to planting them in wide rows. This made it easier to cultivate the fields — a necessary step to eliminate weeds. As the plants got larger, the farmer and his family walked the field to hand pull or hoe the weeds that came up after cultivating.

Corn dryer, circa 1920

View this object in Matterport

Until McLean County farmers chose to plant hybrid seed, they continued to select corn from their fall crop to be used the following spring. This seed corn was dried using devices like these.

Donated by: Dorothy Benjamin

97.132.21

Seed sacks, circa 1950

As early as 1902 Bloomington’s Pantagraph outlined the process of growing hybrid seed. The step-by-step process could be used by anyone to produce their own hybrid seed and increase their yields. Those who tested this process and grew their own hybrid seed often went on to sell it.

From right to left: Charles Gildersleeve & Son Pfister Foundation Hybrid seed sack; Griffith Seed Co. seed sack; Edward J. Funk & Sons Super Cross Hybrid seed sack; National Hybrid Corn Company seed sack; Stiegelmeier Hybrids seed sack; Emile Rediger Hybrid Seed Corn seed sack.

99.54, 97.132.8, 97.132.7, 875.446, 97.132.9, 2002.19.5

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County