Working the Land – 1822 to 1852

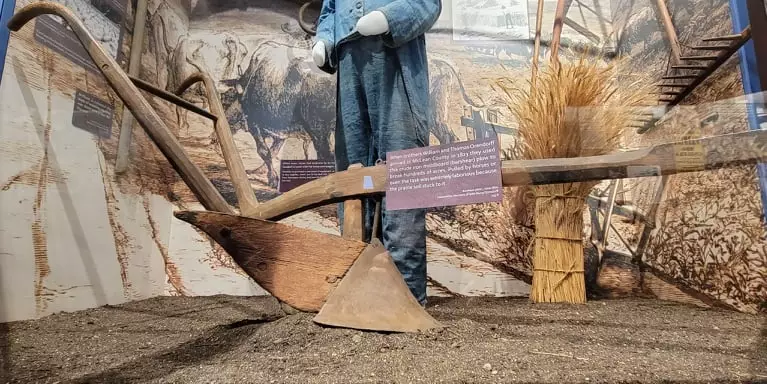

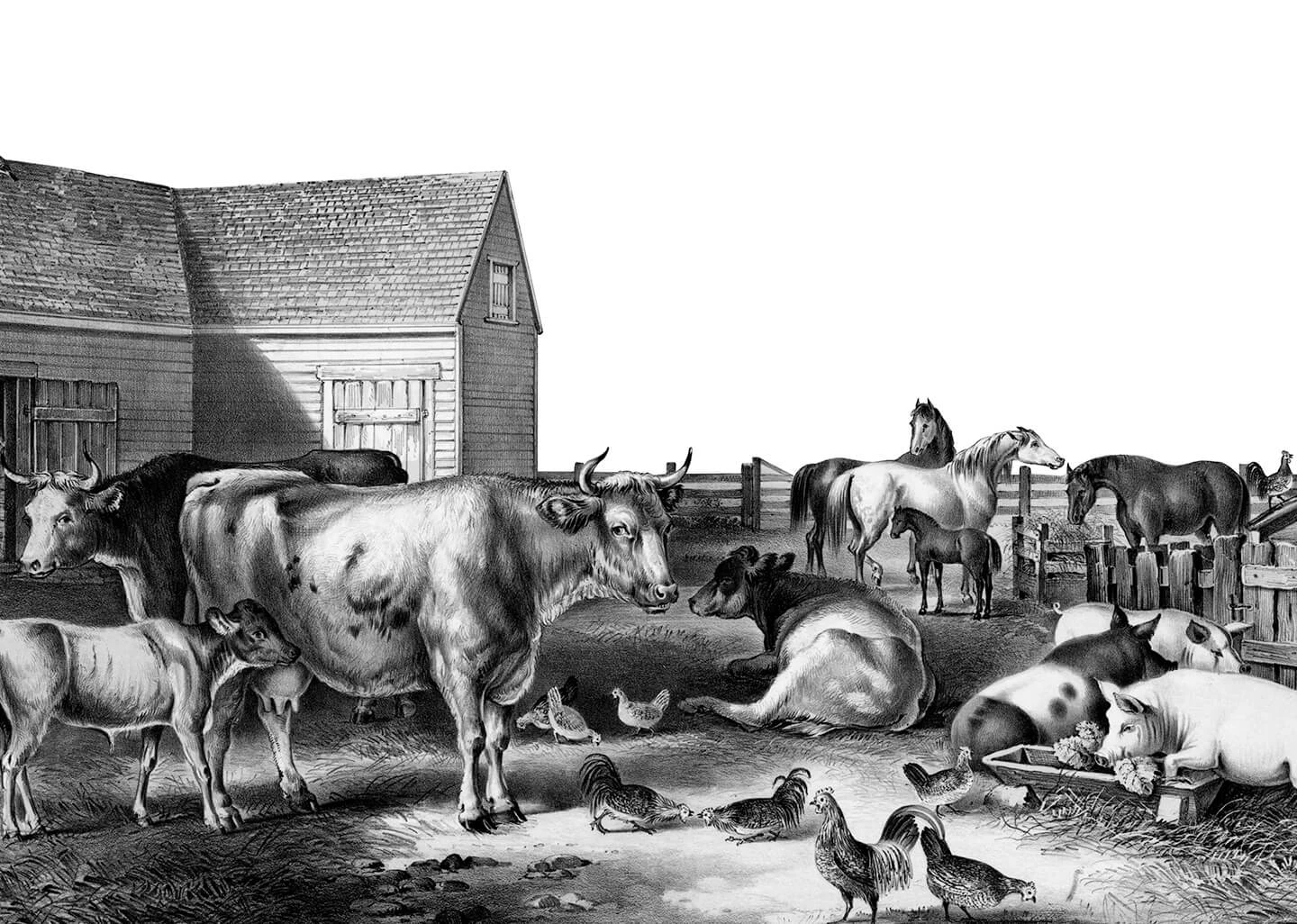

Frontier farmers plowed their fields in strips, then plowed again at a 90 degree angle. “Cross plowing” formed hills in which four to seven corn kernels were planted.

Corn was the frontier farmer’s main crop and was fed to the livestock. By feeding it to livestock, it could be transported to market “on the hoof.”

“One for the blackbird, one for the crow, and one for the cutworm, two left to grow.”

— Cuthbert

1844

Horses, mules, or oxen were used for clearing and cultivating the land. When Mr. Peasley arrived in McLean County in 1834, he obtained a team of four oxen for plowing. He could plow twenty acres before going to the shop to sharpen the shear. To ensure the health of his animals, they were allowed to graze for two hours at noon. Lack of care resulted in the loss of essential animal labor.

Isaac Jones' Ox yoke, circa 1835

View this object in Matterport

Isaac Jones arrived in McLean County in 1836 and purchased 160 acres in Danvers Township for farming. He broke his land using two oxen and this ox yoke.

Donated by: Betty Belle Irvin Porter

2003.47.8

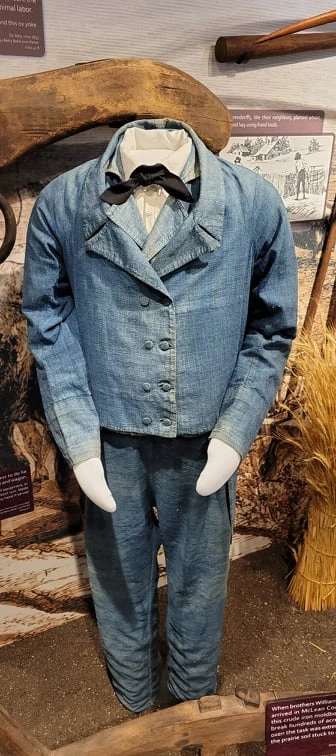

Isaac Jones' homespun denim suit, circa 1840

View this object in Matterport

When Isaac Jones had business to do, he headed to town with his horse and wagon. Whether to purchase a new piece of equipment, or to buy supplies, Jones put on his best suit. Made from homespun denim and sewn by hand, it served him well.

Donated by: Betty Belle Irvin Porter

2003.47.2

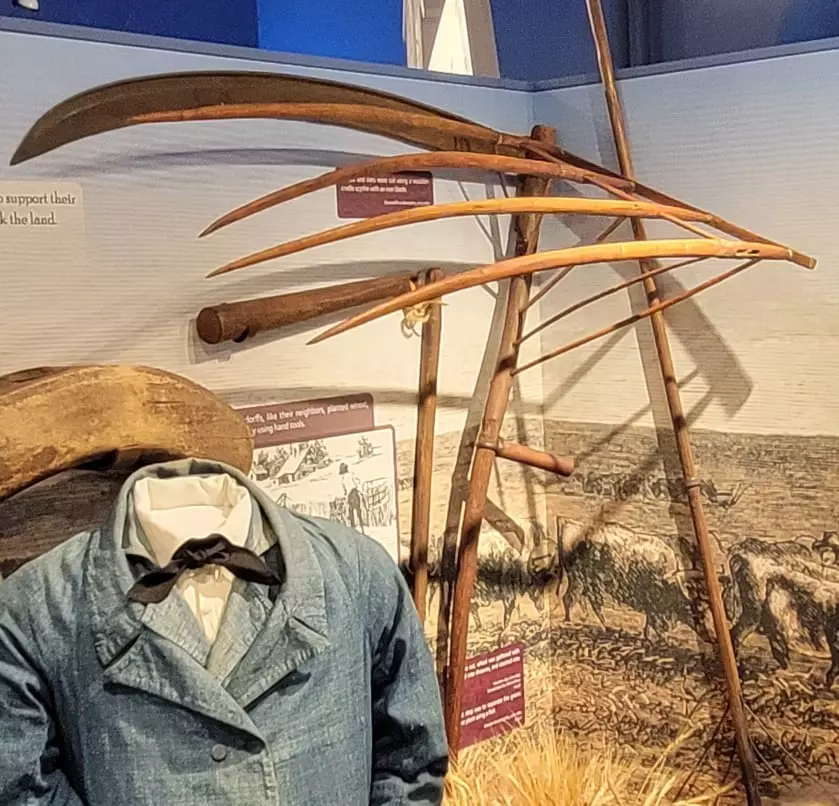

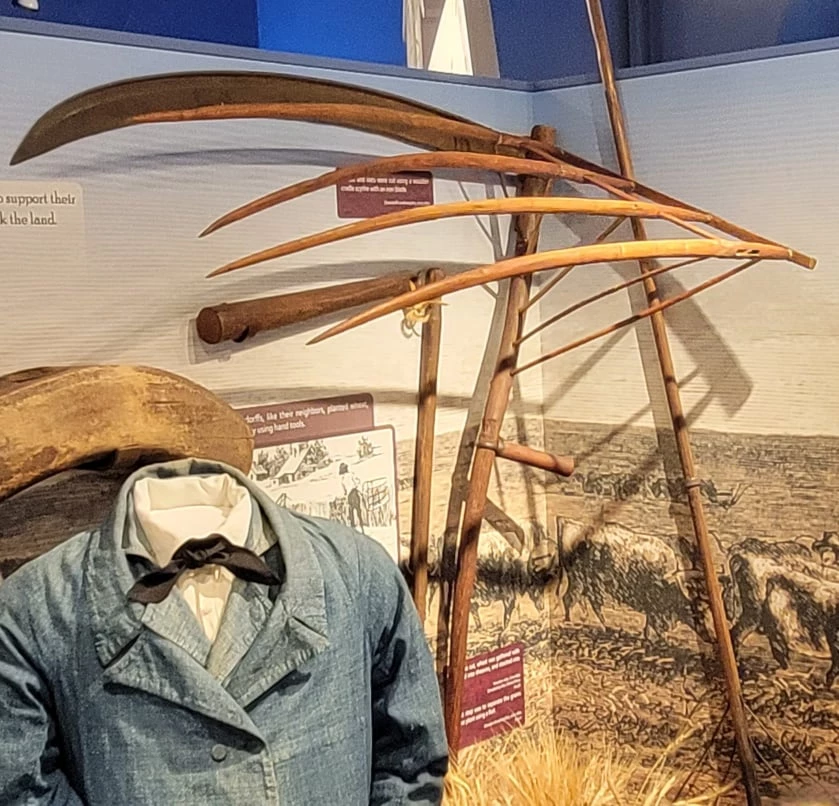

The Orendorffs, like their neighbors, planted wheat, oats, and hay using hand tools.

Orendorff cradle scythe

View this object in Matterport

Wheat and oats were cut using a wooden cradle scythe with an iron blade.

725.8

After it was cut, wheat was gathered with rakes, tied into sheaves, and stacked into shocks. The last step was to separate the grains from the plant using a flail.

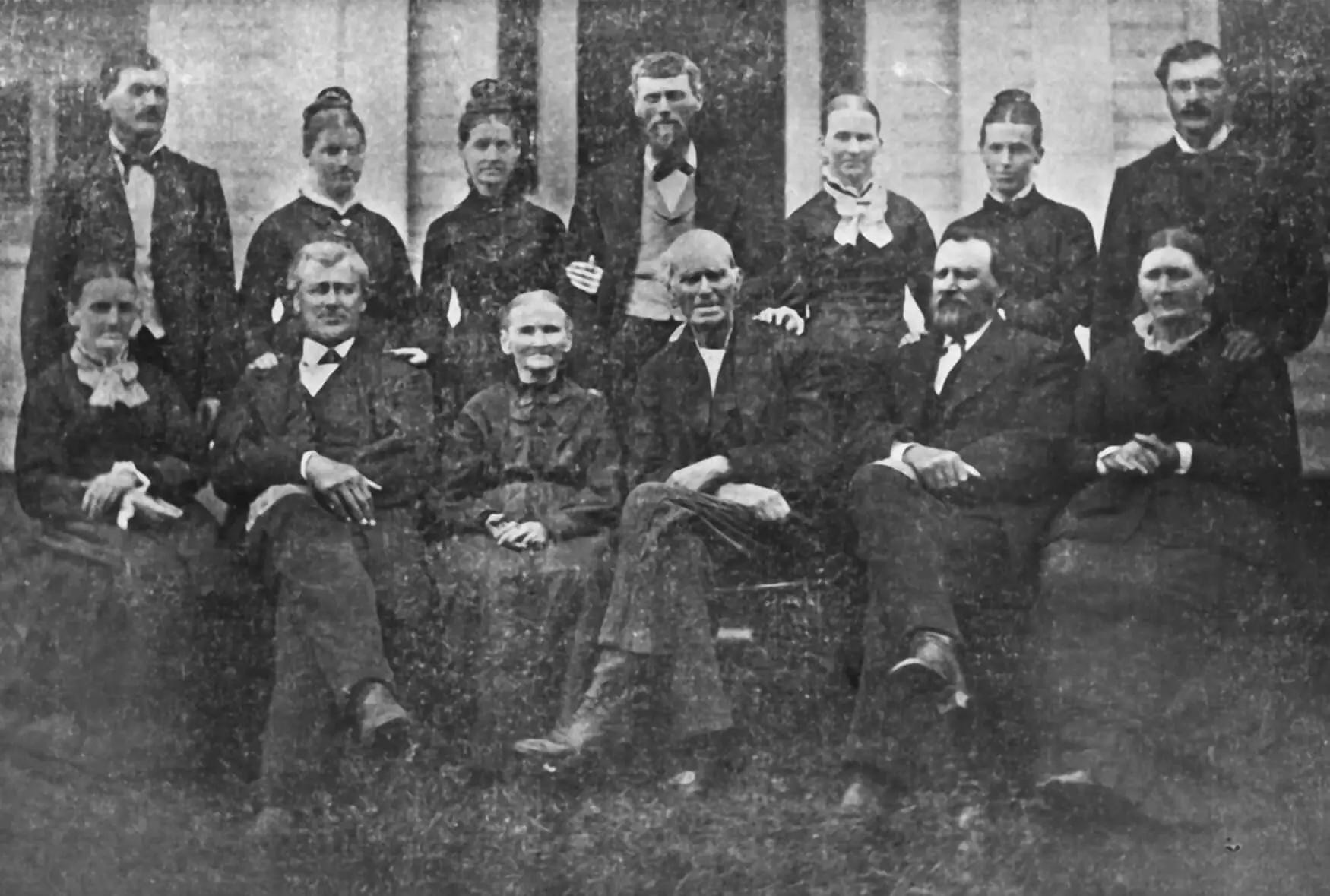

Most frontier farmers like Thomas Orendorff had large families—a kind of built-in labor force.

In 1850 it took 80 hours of labor to produce 100 bushels of grain on just 2-1/2 acres of land. From plowing and planting, to the tending and harvesting operations, many hands were necessary.

Thomas and Mary Orendorff’s 12 children were all trusted with responsibilities at young ages. As their experience increased, so did their responsibilities. With 530 acres of land, there was plenty of work for all members of their family.

John Price first visited Illinois in 1830. By 1836 he had purchased a combination of timber and prairie equal to 720 acres, paying the federal price of $1.25 per acre.

Prime land was purchased quickly by settlers like Price who had the financial resources to pay cash—a necessity as banks rarely made loans for farmland. Nine hundred dollars was a lot of money in 1836 — the equivalent of $23,600 in 2014.

But if Price had arrived in 2014 he would have paid much more than $23,600 as farmland had dramatically increased in value since 1836.

How much do you think it would have cost Price to purchase 720 acres of prime McLean County farmland in 2014?

In 2014 prime McLean County farmland averaged $12,700 per acre. To purchase 720 acres, Price would have paid $9,144,000 — more than 10,000 times the amount he paid in 1836, and over 350 times the inflation rate.

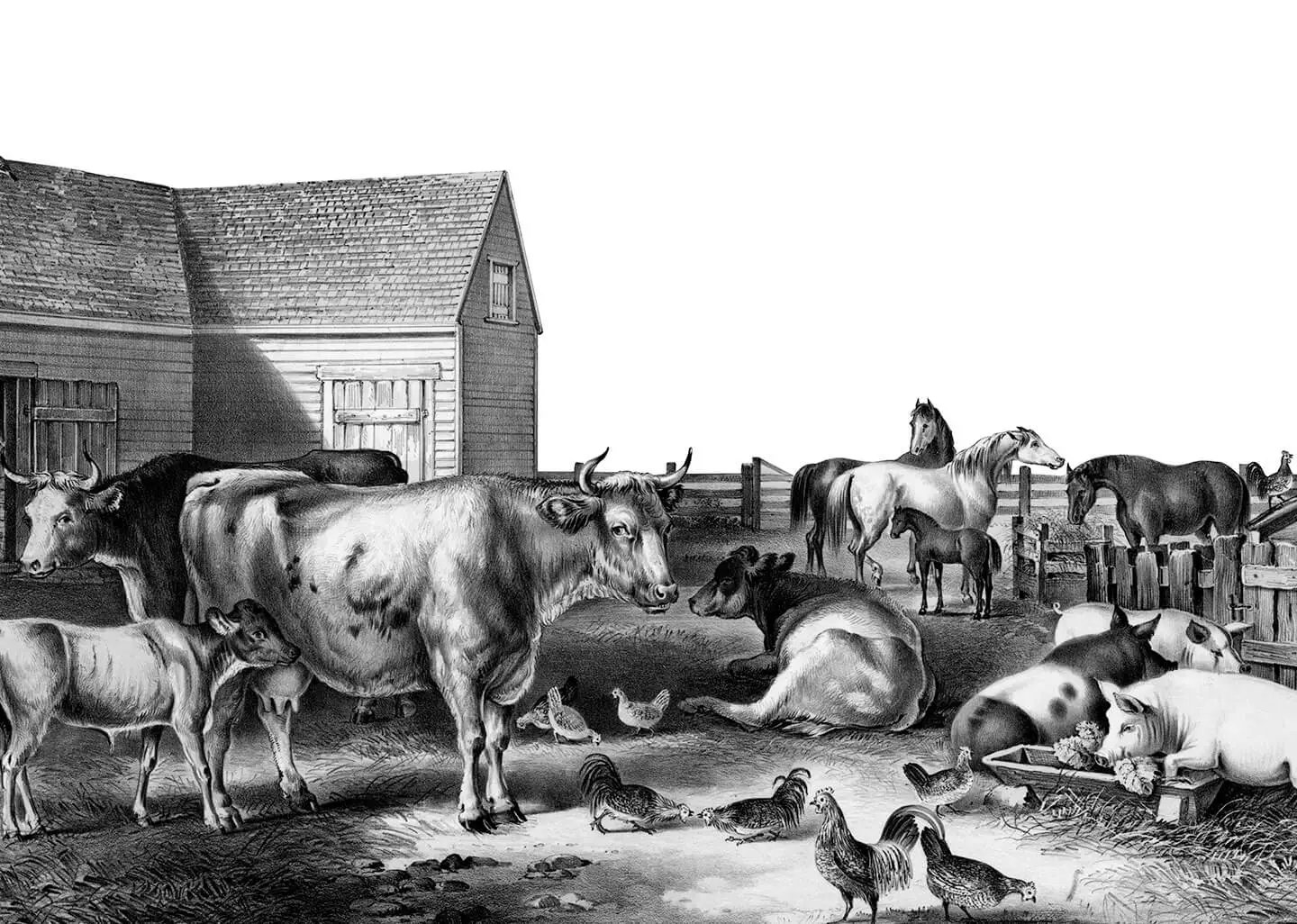

The frontier farmers’ means of making a living was producing grain and livestock for market. But they also had large gardens, small orchards, chickens, and other small animals. Extra hogs and cattle were also raised, which they butchered for themselves.

For McLean County’s frontier farmers, these additional labors were a necessity. With no local merchants selling these food items, they had to be self-sufficient.

As more people settled the frontier and merchants established businesses, gardening and butchering were no longer a necessity. But many farmers continued these activities because they preferred to be less dependent on others.

Farm wives were part of the farm’s labor force too. Often they managed one or more cows that they milked by hand.

The cream was separated from the milk by storing it in earthenware crocks placed in a cool spring house or cellar, where nature did the work in about 48 hours. The cream was made into butter, and the buttermilk was fed to the hogs.

Wheat, oat, and hay crops were used to fatten livestock. As a result these crops made it to market “on the hoof.” Some wheat was ground into flour for cooking, while some was sold or traded in town for items like sugar, coffee, or dry goods they could not produce on the farm themselves.

Reaping hook, circa 1865

View this object in Matterport

Reaping hooks like this one, which took less skill than a cradle scythe, were also used to cut crops and weeds. This one was used by members of the Orendorff family.

Donated by: James Orendorff

775.205

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County