Working the Land – 1853 to 1899: Labor

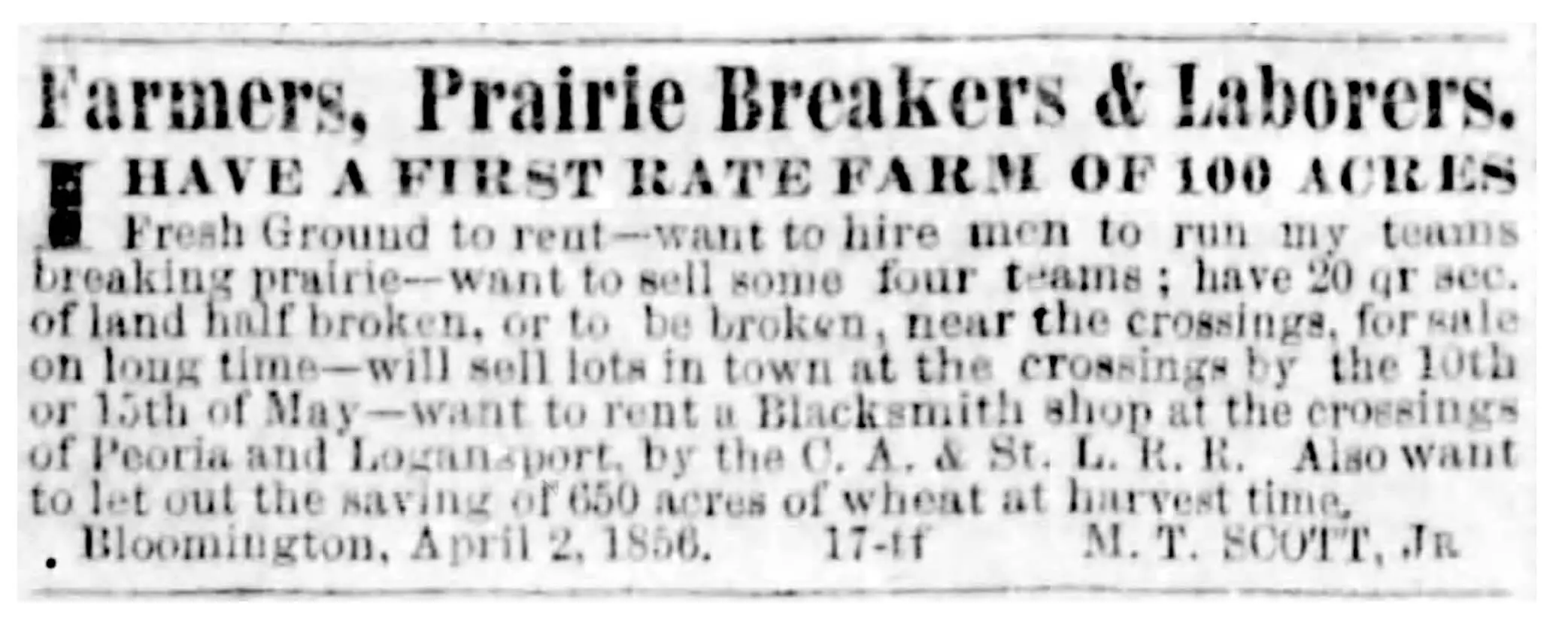

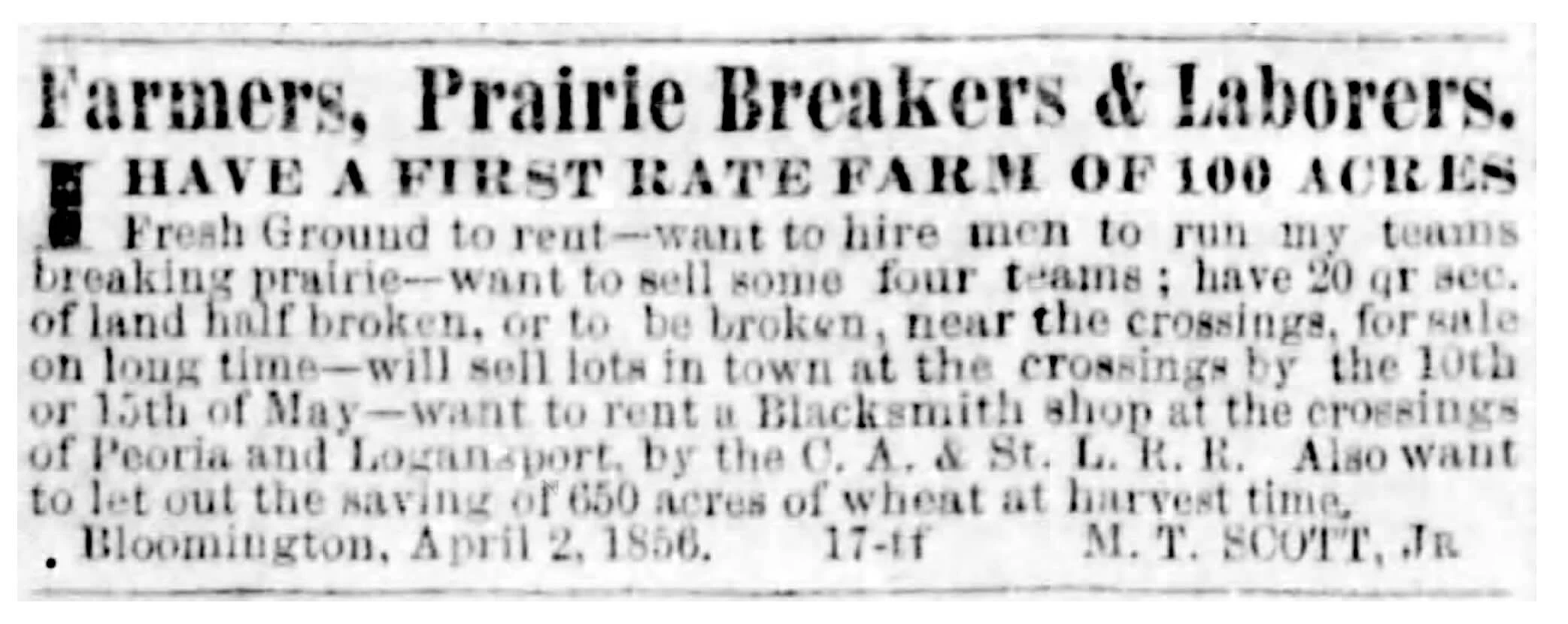

As farms got larger in size, some farmers could not do the work alone. They hired immigrant laborers to help. Some immigrants arrived ready to farm — others with little, if any, experience.

Isaac Funk relied on “share crop” farmers to work some of his 24,000 acres of land in exchange for a portion of the crop.

Share crop farmers (also called tenant farmers) worked the land in return for a share of the crops they produced.

Agreements varied, but tenant farmers typically planted, cultivated, and harvested the crops, and maintained the land. They shared the cost of seed with the owner, while the owner was responsible for constructing and maintaining farm buildings and paying property taxes.

By 1850 Isaac Funk managed up to 2,500 head of cattle per year—feeding them corn and hay in the winter, and turning them out onto the prairie to graze in the summer. To accomplish this he grew 1,200 to 1,500 acres of corn and hay for winter feed and maintained 10,000 acres of prairie for grazing. According to an 1850 Chicago Tribune story, “Some of the finest cattle brought to this market were from the farm of Mr. Funk. He is the right kind of man for this business.”

S.H. Seitz, a highly regarded tenant farmer near Gridley, made a living as a diversified farmer.

Seitz had a crop share agreement with his landlord George Perrin Davis in 1893 — half the corn crop and two-fifths of the oats, delivered to the elevator.

Seitz chose what to plant and where, and annually produced about 5,000 bushels of corn to fill his cribs and 7,500 bushels of oats, which he stored in the farm granary. He fed his share of the corn to his livestock and, when needed, purchased his landlord’s share.

Farmers Voice magazine writer Arthur Bill had high praise for Seitz’s work:

“When many a cornfield was in a cloddy condition, even after much work... Mr. Seitz’s fields were all level and smooth and finely pulverized, as well as entirely clean of weeds.”

— Arthur Bill

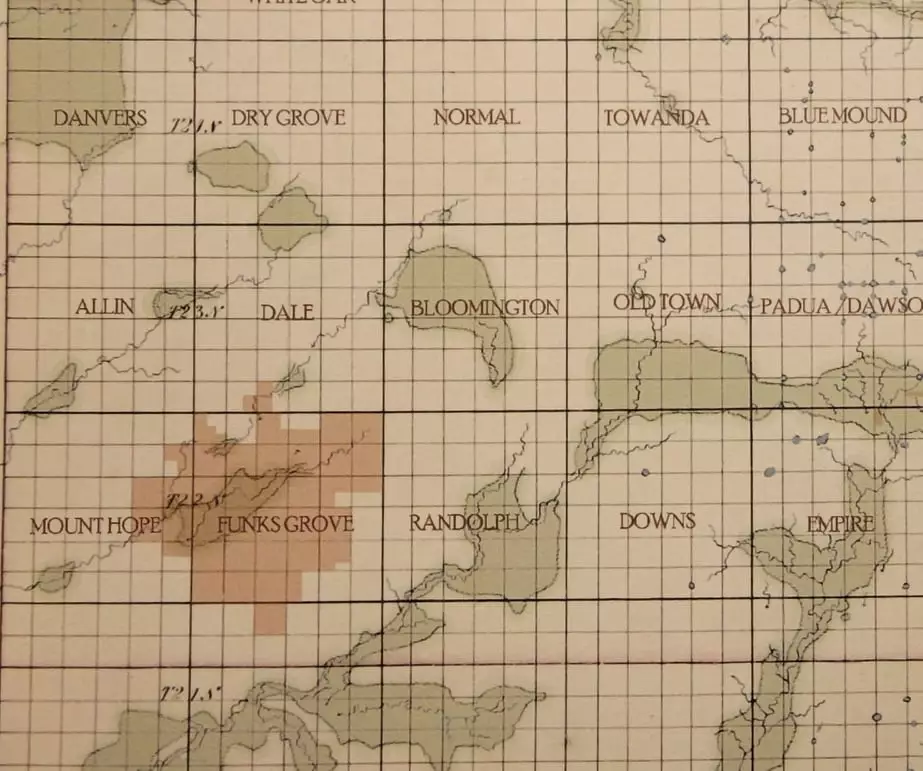

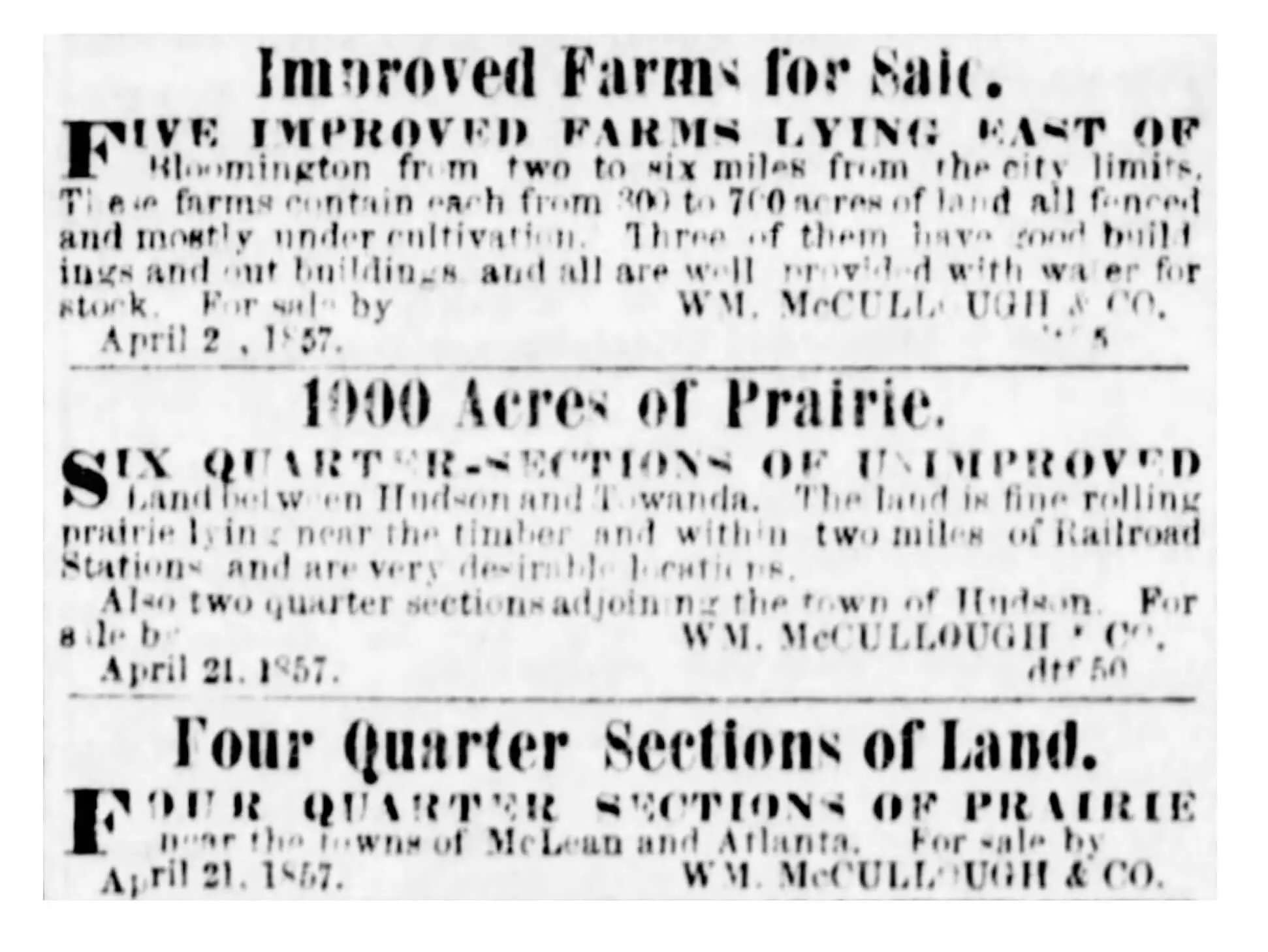

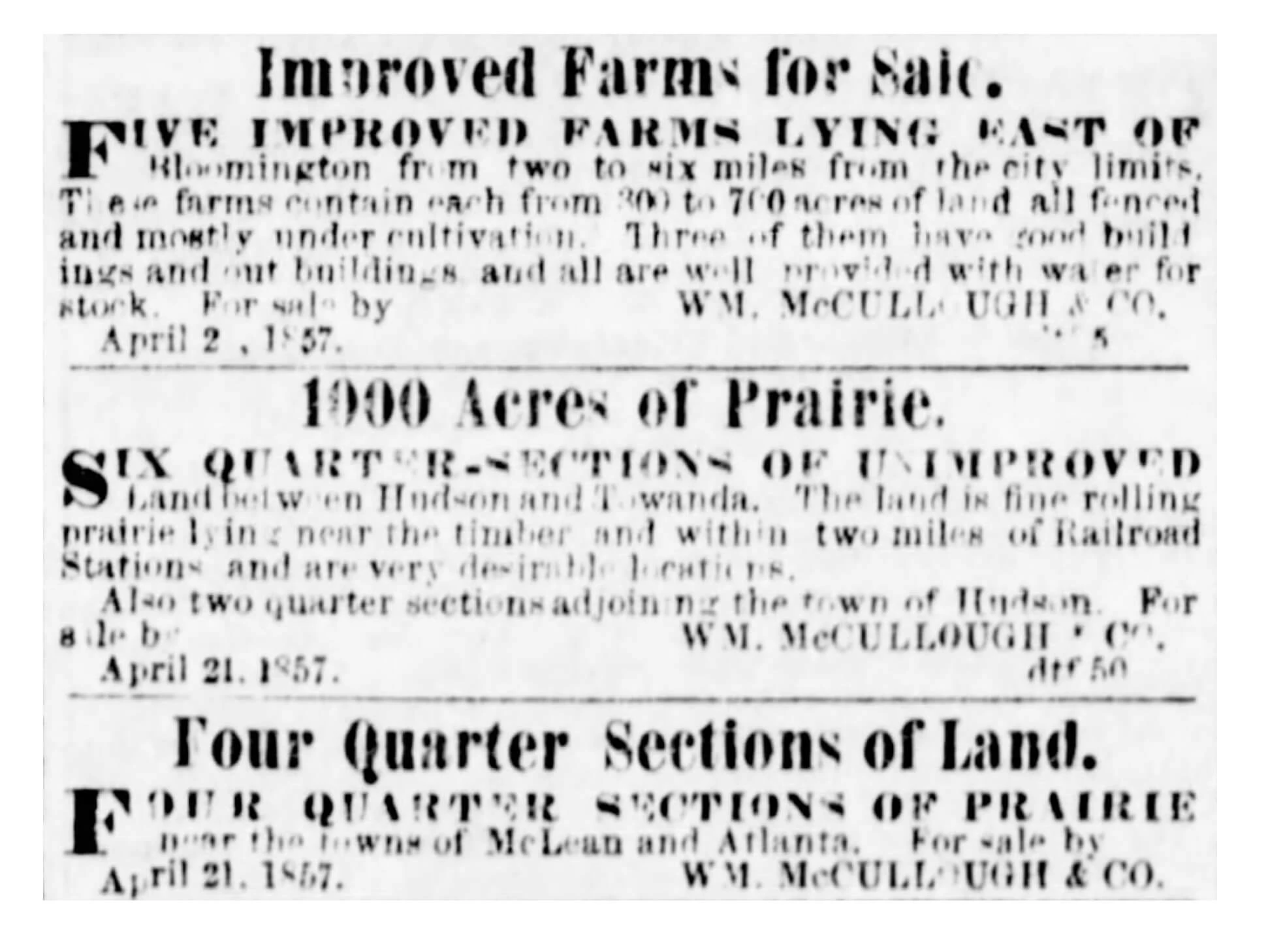

When the railroad’s route through McLean County was determined, the price of land adjacent to the route, originally priced at $1.25, immediately rose to $12 per acre. Land a few miles from the route increased to about $2.50 per acre.

By the late 1870s all federal land had been sold. A considerable amount was purchased by speculators hoping to sell it for handsome profits. Many of these parcels were sold to farmers.

Between 1850 and 1880 the average farm size decreased from 158 acres to 124 acres. The number of farms in McLean County peaked in 1880 at 5,466.

As they gained experience, immigrants that started as farm laborers found landlords willing to crop share.

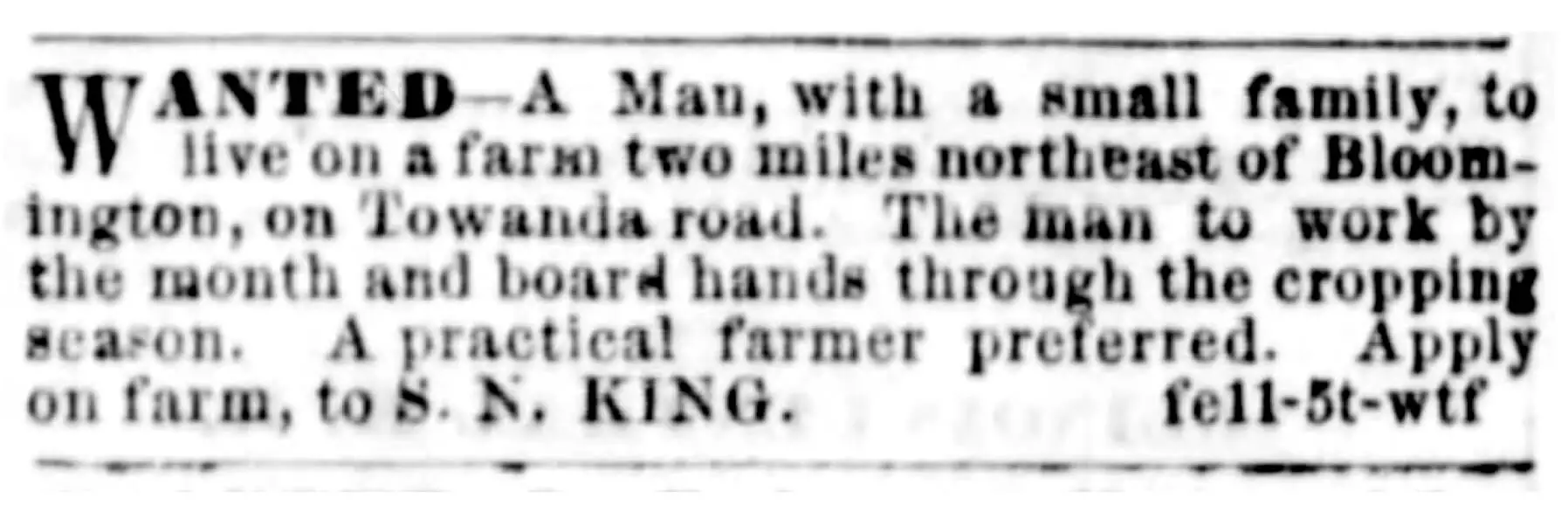

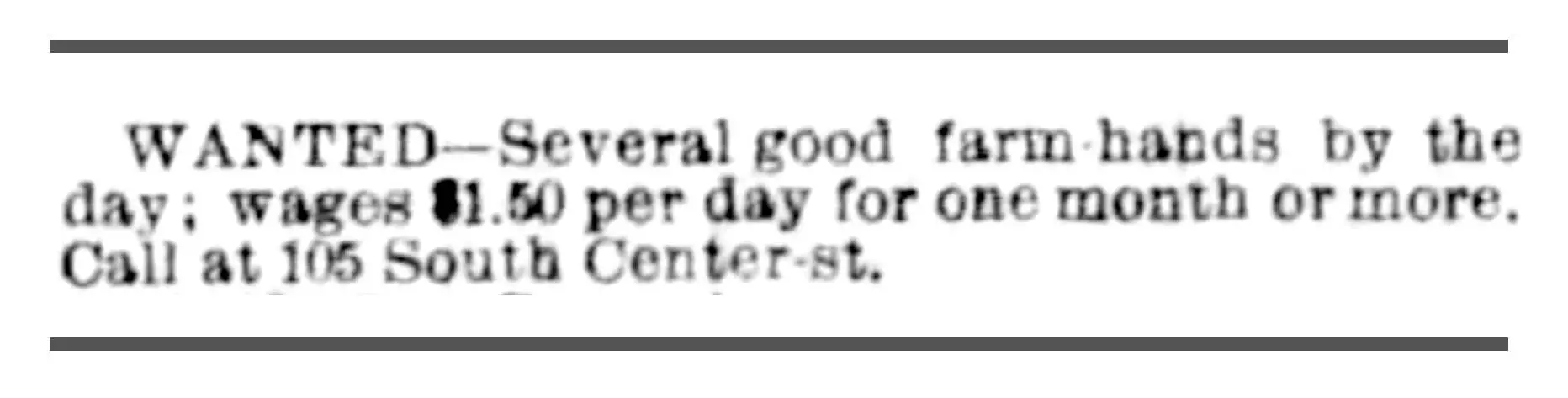

Bloomington’s Pantagraph regularly published advertisements for farm help.

In the fall of 1879 the Bloomington Pantagraph reported:

“There never was such a scarcity of hands before in East Downs, almost every farmer wanting from two to three.”

— Bloomington Pantagraph

As farm production increased, so too did the need for animal labor.

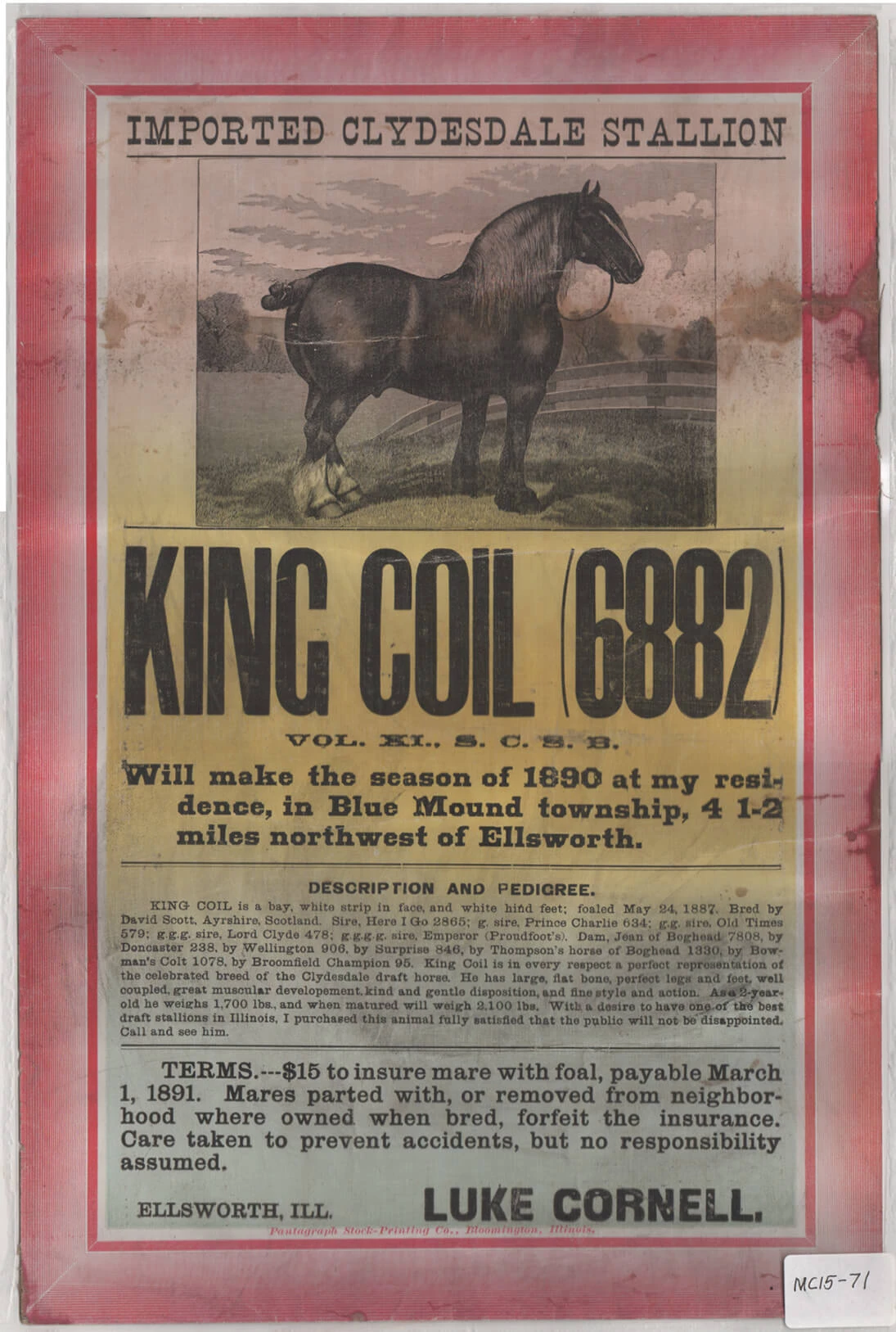

Horse power was necessary for pulling wagons, cultivators, planters, and other equipment, though some farmers used oxen.

Quality horses were readily available from one of the many McLean County horse merchants, or the local farmer could have his mare bred to a “rented” stallion.

Luke Cornell of Ellsworth offered his registered Clydesdale stallion, “King Coil,” for breeding in 1890. For $15 his stud would impregnate a farmer’s mare.

Cooperative efforts between neighboring farmers turned the laborious tasks of hay making, grain threshing, corn husking, and barn raising into lively social events.

In order to make threshing wheat more affordable, neighborhood farmers often put together a “run” of multiple harvest jobs, then split the cost needed to hire a thresherman to operate his steam engine and threshing machine. Crew members loaded the shocked grain onto a wagon, delivered it to the threshing machine, transferred the shocks into the threshing machine, and stacked the straw. A long belt from the steam engine transferred power and turned the threshing machine’s gear to separate the grain from the stems.

As the farm families worked together they swapped stories, shared ideas, and developed friendships. Farm wives prepared lavish meals, often attempting to outdo each other. An evening of dancing and socializing often ended the day of hard labor.

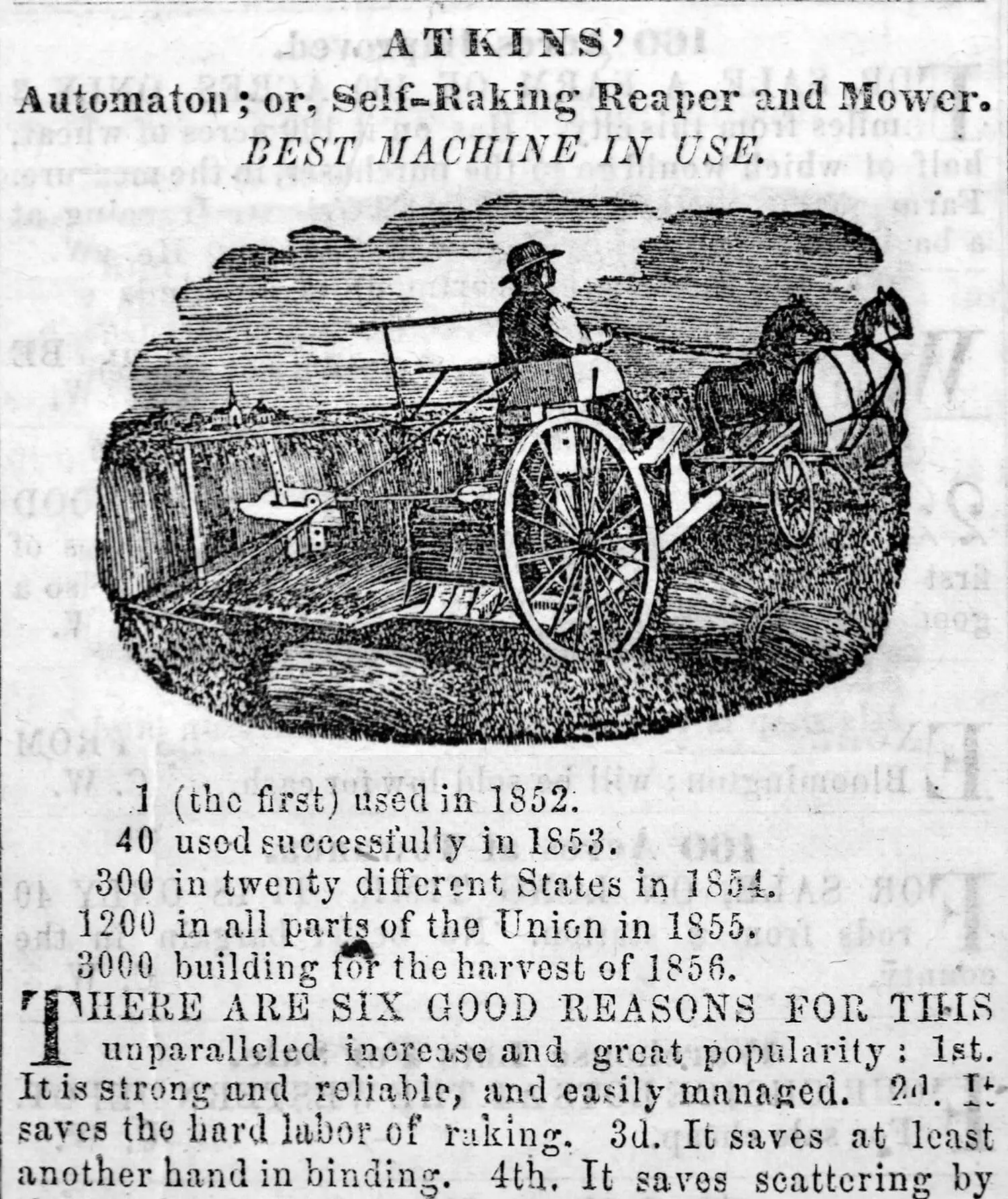

As innovative new machinery arrived via the railroad, McLean County farmers made hard choices — picking and choosing to invest in the new technologies that best suited their needs.

Stout’s Grove farmer Joseph E. Springer purchased an Atkins’ reaper from Morehouse and Company, a Bloomington hardware store, in 1856.

“It did most excellent work — much better than any other I ever used . . . I confidently recommend the Atkins’ Reaper to farmers desiring a good machine.”

— Joseph E. Springer, 1856

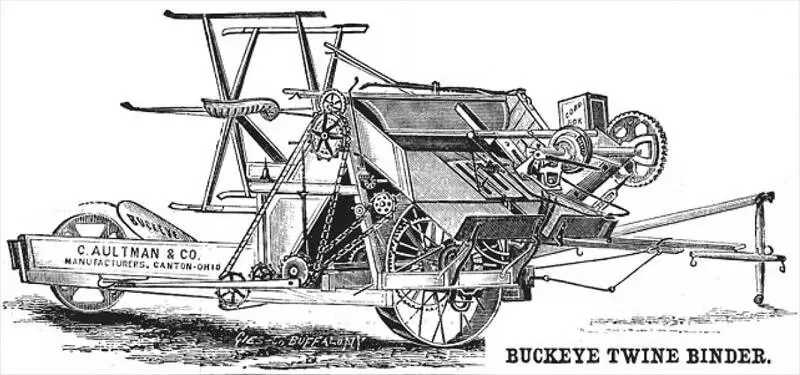

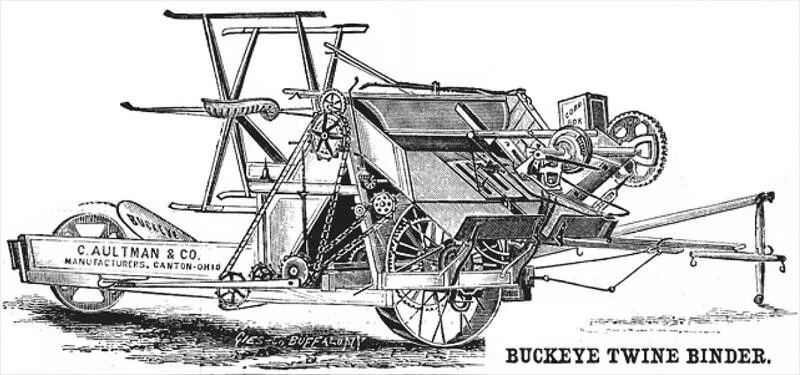

Simon Moon farmed his own land north of Bloomington, as well as the John Gregory farm south of Gridley. He invested in a mower reaper for his wheat in the 1880s that had a twine binder, but chose not to purchase a picker binder for his corn. Both were labor and time saving devices.

According to Moon’s records, it took 14 hours of labor to cut wheat with a scythe. His new reaper both cut and bound an acre of wheat in 1.5 hours.

In July of 1882 Bloomington’s Pantagraph reported that over 500 of the newest self-binding reapers had been purchased by area farmers from local dealers. At about $300 each, that was a local investment of $150,000!

Moon, like many other McLean County farmers, continued to pick and shuck corn by hand — a process that took about 15 hours per acre.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the quality of corn was judged based on how it looked on the ear.

Each year farmers picked out the biggest ears with the most even kernels to plant the following year.

In doing so they planted the corn with the least amount of starch (the component most needed for feeding livestock). By doing this year after year, the amount of starch was reduced.

At the turn of the 20th century, local, regional, state, and national festivals featured corn competitions — a kind of beauty contest where six to ten ears of corn were judged based on how they looked, not by scientific evaluation of the quality of the seed. These popular festivals often included the decoration of the building (both inside and out) with corn and other plant materials. Bloomington Corn Festival, 1916.

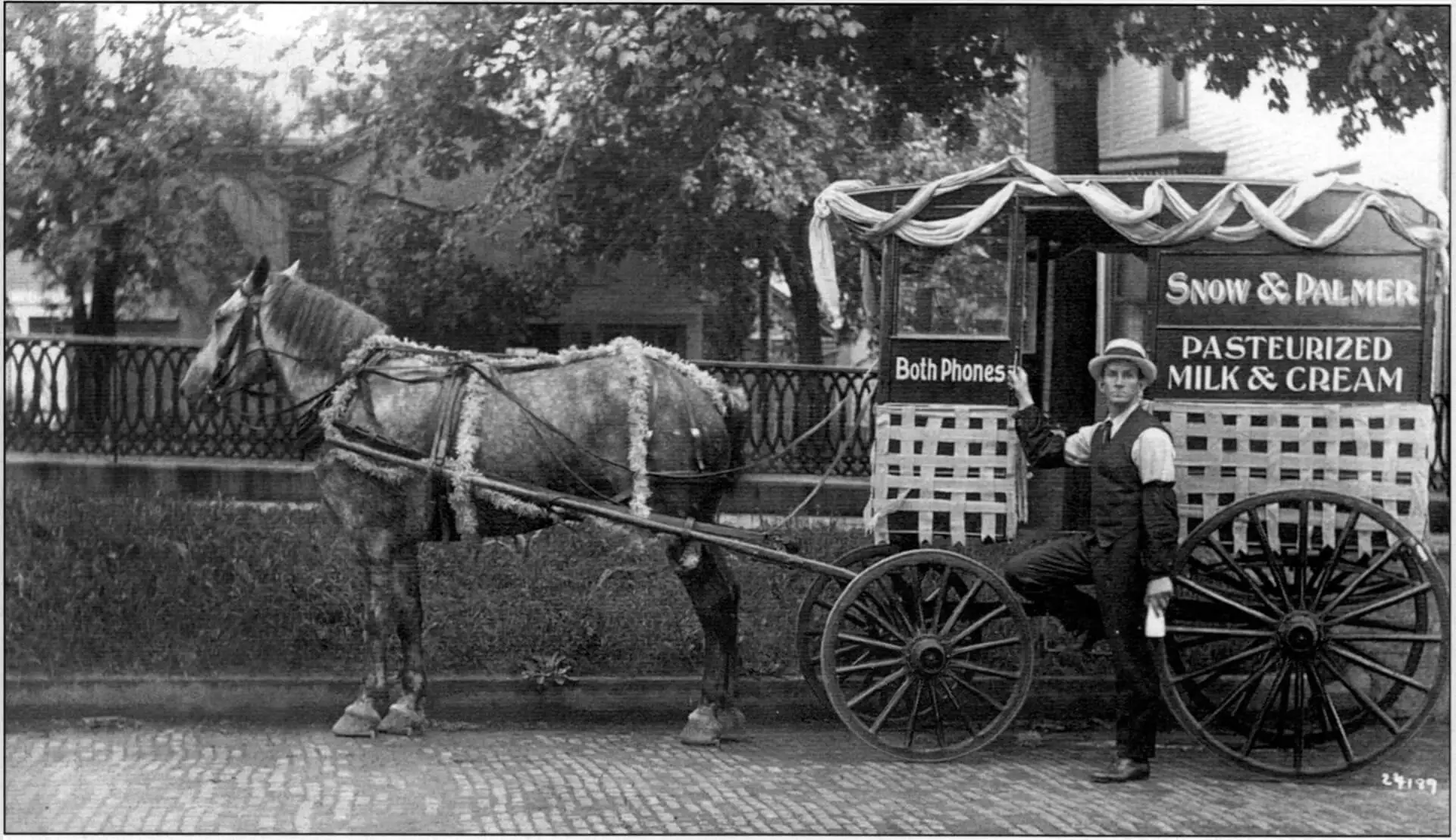

Despite a great demand for butter and cream in Bloomington, until the late 1870s there were few McLean County farmers who chose to have sizeable dairy herds — milking cows twice a day by hand was hard work!

Because an ice house or cold water spring was necessary to keep milk cool and unspoiled in the summer, most McLean County farmers only produced milk for themselves. The cream was made into butter, and the buttermilk was fed to the livestock.

In the 1890s Calvin Barnes, owner of Larchwood Dairies near McLean, shipped 30 to 40 gallons of cream to Bloomington a week to be made into ice cream.

During winter months, when there was less demand for ice cream, Barnes used a steam engine to churn his cream into butter 150 gallons at a time. He fed the remaining buttermilk to his calves and hogs.

At the time Barnes had the only area silo for the storage of silage—a valuable source of feed for his dairy cows.

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County