Nature's Forces – Nature's Forces

Too hot, too cold, too windy, too rainy, or too dry — no matter how a farmer shuffled the cards, Mother Nature controlled the deck when it came to weather.

Nature's Forces: Weather

Lighting strikes could destroy crops, buildings, and animals.

In the fall of 1826 lightning struck Funks Grove, starting a prairie fire that destroyed everything in its path.

The plants of the prairie ecosystem were adapted to fire, and thrived with it as part of their life cycle. On the surface grasses died every fall, creating thatch that kept the ground cool and moist. But in the spring, plants needed light and heat. Fire recycled nutrients from the thatch into the soil. In the spring, fire blackened soil warmed quickly, helping the new plants get an early start.

“The whole heavens were lit up, and at midnight everything was almost as easily and clearly distinguished as at midday. In the morning the whole country was black, and many [hay] stacks and rail fences were simply smoking cinders.””

— The Good Old Times in McLean County, E. Duis

Prairie fires were often started purposefully — a practice learned from Native people. By burning the prairie grasses after the frost had killed the vegetation, and pasturing it heavily the next summer, farmers gradually eliminated the tall grass and the potential for prairie fires started by lightning.

Due to lack of rainfall and intense heat, significant yield reductions were already being predicted in late June of 1988. As he cultivated near Heyworth, Clarence Thomas could see the evidence — the leaves on his corn were curled up tightly to reduce evaporation. By the end of August, Illinois had recorded the driest period on record since 1895.

In the early hours of May 25, 1925 a late freeze severely damaged area farmers’ new corn.

By 7 a.m. E.D. Lawrence of Dry Grove Township was in town looking for new seed to plant. By afternoon others were already replanting. But Covell farmer S.C. Beeler sat back and waited — advising others to do the same.

Beeler recalled the freeze of 1895, when 40 acres of damaged new corn resprouted four days later. He decided to wait and see what happened.

That summer McLean County experienced extreme heat, but Lawrence and those who followed his lead still had decent crops. Those who replanted had smaller yields as their replanted corn never reached full maturity.

Cloud Seeding

In the early 1970s McLean County farmers experienced several years of dry weather.

Disappointed by low precipitation in the spring of 1977, some decided to take nature into their own hands.

Cloud seeding had been tried in other areas of Illinois, so a local group, Rain Gain Inc., organized and raised the money to hire professional cloud seeding aircraft pilots and meteorologists with sophisticated radar.

“Seeding” involved the release of silver iodide crystals into rain clouds not for the purpose making it rain, but to increase rainfall. After several attempts with underwhelming results, the corporation dissolved.

Tornados

On August 24, 1982 at least three tornados tore through Central Illinois destroying buildings and causing extensive damage to thousands of acres of Illinois corn.

Farmers, like Bob Landau of Anchor, who had 300 acres of flattened corn, believed they had lost much of their crop. Wanting to maximize their harvests, Landau and his neighbors investigated their options and paid about $2,850 each to purchase special “Corn Saver” heads for their combines.

The heads were designed to lift flattened corn to capture more of the ears that would otherwise drop to the ground and be lost.

With the special head, Landau believed that he only lost about five bushels per acre and that the unit paid for itself in saved corn. Some of his neighbors ended up with bumper crops.

Nature's Forces: Insects

Insects also wreaked havoc on farmers' crops.

In 1871 thousands of tiny chinch bugs began to consume James W. Keeney’s Martin Township corn field. But Keeney was determined to stop the bugs using a method he had read about in a farm magazine.

Keeney got to work and plowed a large furrow ahead of the advancing insects. On the corn side he poured a line of coal tar.

The bugs traveled to the tar ridge, then turned down the furrow, dropping into one of 75 pits he had dug along the furrow. At sundown he poured strong soap suds in the pits, which killed the bugs.

After two weeks of hard labor, the use of three barrels of coal tar, and the removal of 35 bushels of dead cinch bugs, the remaining insects headed to his neighbors field.

In 1937 an infestation of grasshoppers ravaged the soybean fields of McLean County.

With the help of Lloyd Rodman, Shirley farmers Avery Adams and Harry Morgan built a “hopper dozer.”

A tank filled with two inches of kerosene and surrounded by a canvas backstop was secured to the front of Adams’ truck. As it was driven through the fields, the truck disturbed the grasshoppers, which hit the backstop and fell into the kerosene tank where they quickly died.

According to reports Adams captured 50 bushels of grasshoppers from a single field. Similar contraptions had been developed as early as 1874 when grasshoppers consumed Kansas crops. The contraption was such a success that MGM sent out a camera crew to film a newsreel about it.

Nature's Forces: Weeds

Farmers have struggled to control the weeds that competed with crops for water and nutrients for hundreds of years. Good tenant farmers worked especially hard to eliminate weeds, which reflected badly on their farming skills.

Even after weed controlling herbicides became available in 1946, farmers still had to cultivate their corn, hire workers to walk their beans to remove the weeds, or do it themselves.

Nature's Forces: Animal Diseases

Animal diseases have impacted the success of many McLean County livestock farmers.

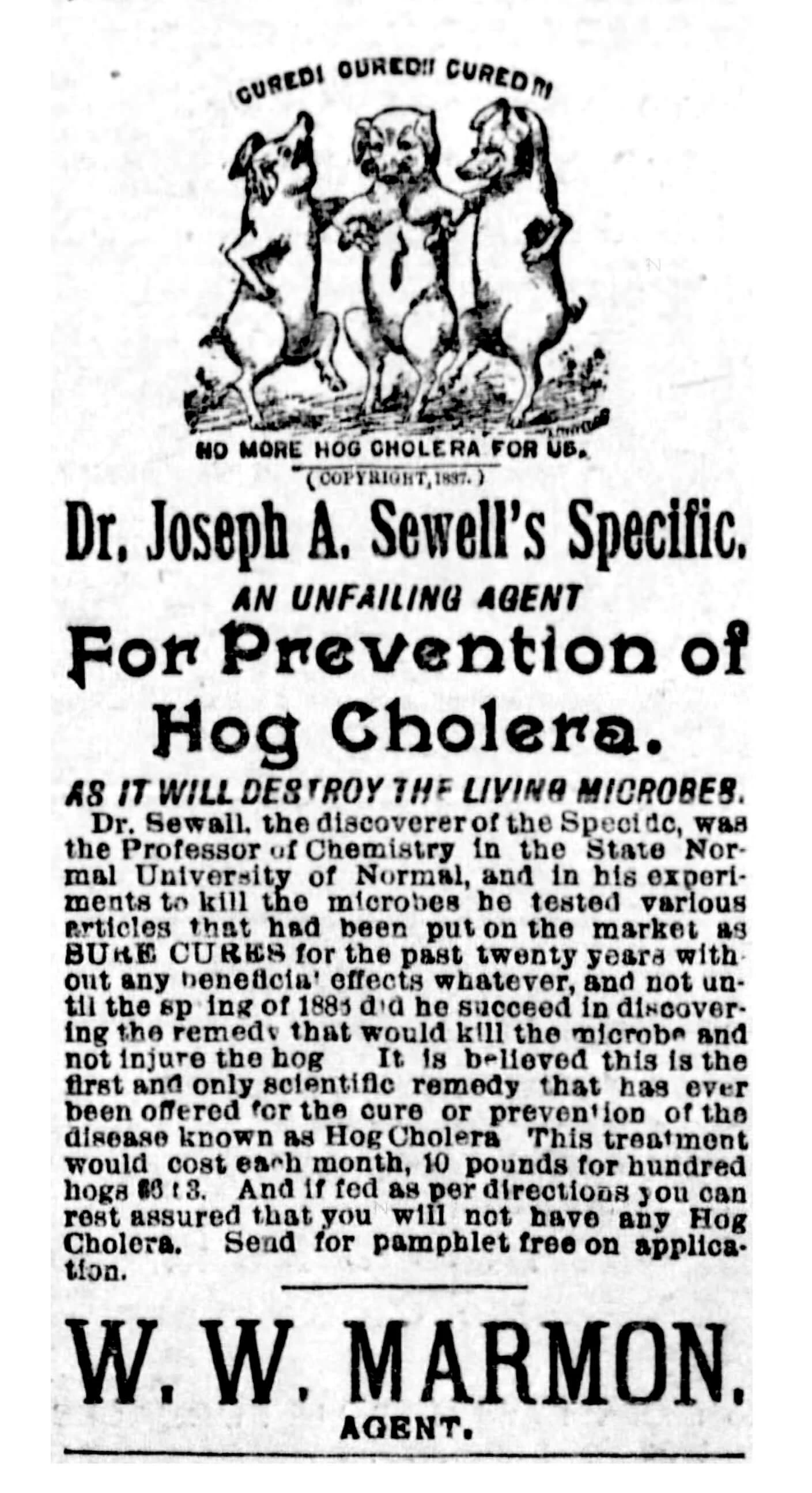

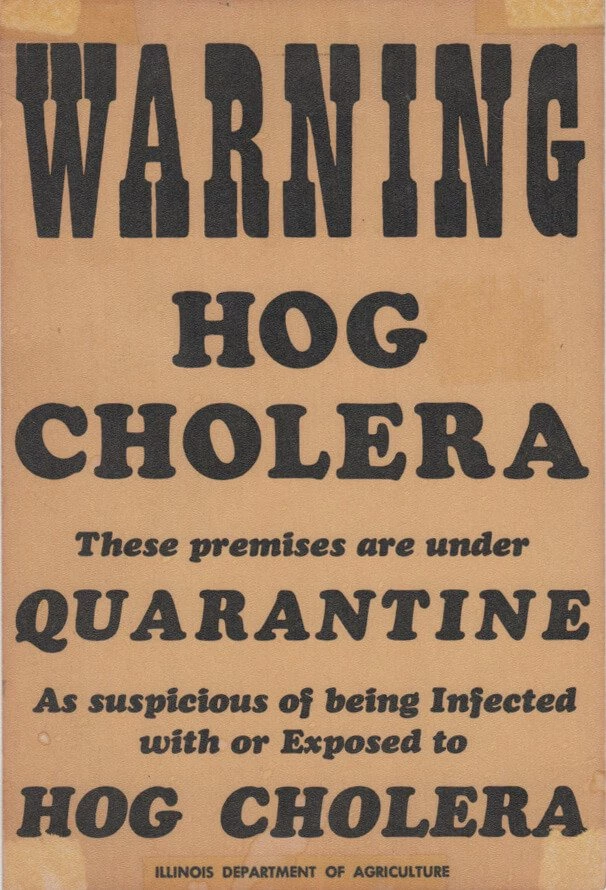

McLean County’s hog feeders faced a serious outbreak of hog cholera in the winter of 1886-87.

That winter many desperate farmers purchased Dr. Sewell’s hog cholera cure which was advertised in the Pantagraph.

Despite his status as a professor of chemistry at Illinois State Normal University, the claim of a “cure” was false and those with one or more hogs infected in their herds lost 90 percent or more of their hogs.

Arrowsmith farmer George Hedrick was a successful hog feeder until the 1870s, when he lost nearly 200 pigs to hog cholera. Afterwards he decided the risk was too great, and turned his focus to cattle and sheep.

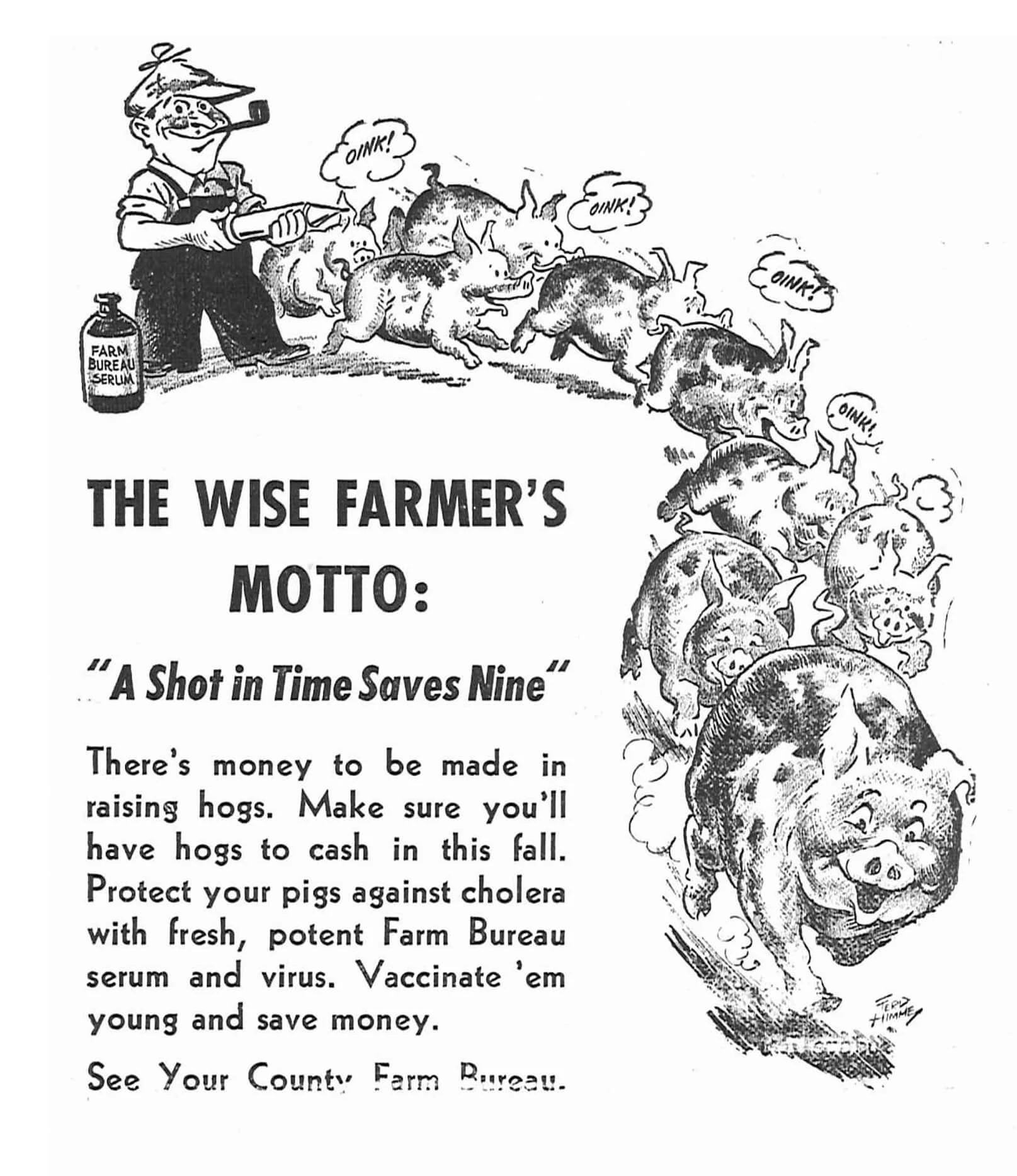

Hog Cholera Vaccine

The development of a vaccine in 1903 reduced the incidents of hog cholera. But many McLean County farmers chose to spare themselves the expense.

Ten years later an outbreak of hog cholera decimated most of McLean County’s swine herds. But the herds that were vaccinated were spared. Most learned their lesson and thereafter vaccinated their herds.

The McLean County Farm Bureau provided its members with cholera vaccinations at cost. The bureau also promoted the fact that smaller doses were needed for young pigs and saved the farmer more money.

Hog cholera was eliminated in 1978 when an antiserum was developed for a variation of the virus discovered in 1949.

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County