Working the Land – 1946 to 2000: Corn and Soybean Crops

Low or no-till practices were radical when first introduced to McLean County farmers in the early 1970s by Herman Warsaw and widely promoted by Jim Kinsella.

A passionate advocate of no-till practices, nearly 100,000 farmers from around the world visited Jim Kinsella’s farm to see successfully applied no-till farming practices.

Gone were the plows that turned soil over, exposing it to wind and water erosion — replaced by chisels, disks, and shanks that cut the crop residue (plant material from the previous crop) and loosened the soil without turning it over.

Some farmers delayed the transition to no- or low-till because it required the purchase of expensive new equipment and depended even more on the use of weed control herbicides, which were also expensive.

With less or no money invested in livestock, farmers had capital to invest in bigger equipment. With the average number of acres per farm continuing to increase, this was a necessity if they wanted to get the job done.

In 1981, after a two week rain delay, Bloomington farmer Dennis Wentworth worked 14-hour days in order to get his soybeans planted.

With limited capital to purchase his own equipment, this young farmer invested in Wentworth Ag., Inc., a corporation that purchased the equipment. Investors shared this equipment.

That same year Harold Smith prepared a new John Deere Max Emerge 16-row corn planter for use on the Funk Trust farm near Shirley. The new planter used a vacuum system that insured accurate placement of the seed. It also had dry fertilizer tanks.

Yields for soybeans, McLean County’s second most profitable crop, increased by as much as 400 percent as a result of higher demand, improved seed varieties, and switching to a more dense planting system.

In 1982 Gridley area farmers Dave and Fred Gilman used a Crust Buster drill to plant soybeans in 10 inch rows in a no-till field planted with corn the previous year. Before planting they surface sprayed herbicides to help keep down weeds.

Improved herbicides reduced weeds, but soybeans still needed to be walked. On many McLean County farms the task of walking through the rows and cutting or hoeing out the weeds was a family affair.

Bob Hartzold paid his kids to walk beans on his Dry Grove farm until they went off to college. Then he had to find others to do the job.

“...I hired a Hispanic family, José Luna’s family, in the 1980s... I have never hired anybody that has been more efficient and more determined to do a good job...”

— Robert Hartzold, Farm Memory Program, 2015

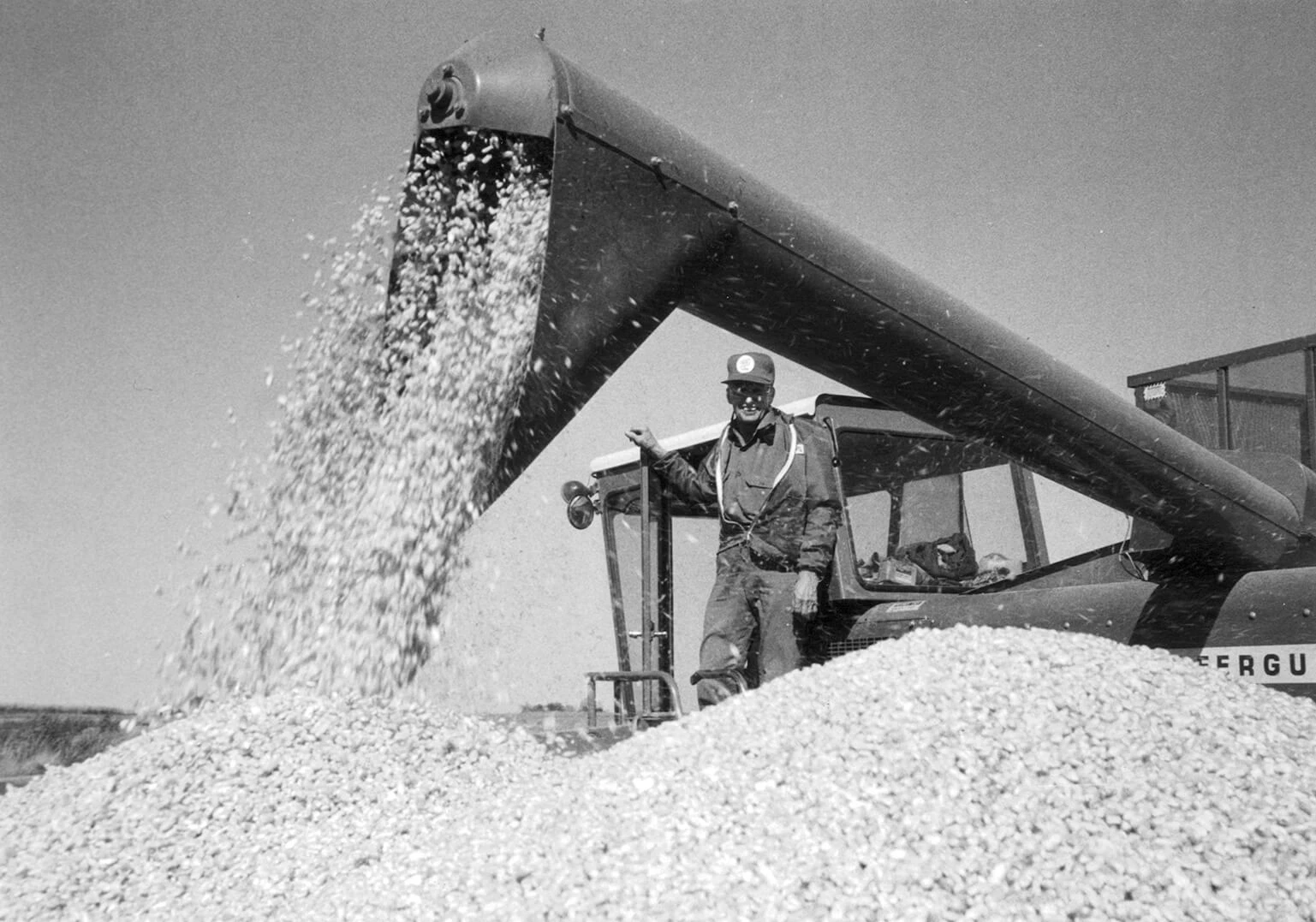

Lester Fuller and his farm manager Bob Davis couldn’t wait for a commercially produced corn combine.

Instead, they began experimenting. In 1950 they “combined” a picker and a sheller together in a manner that allowed them to complete both jobs in the field. In the next two years they continued to work, eventually creating the riding combine pictured to the right.

With most McLean County farmers focused on crops, by the end of the 20th century McLean County was the world’s largest corn producer.

More than anyone else, Herman Warsaw of Saybrook knew how to get good yields from his corn fields.

In 1975 Warsaw produced 338 bushels of corn per acre, an accomplishment that still holds the world record for non-irrigated corn. Warsaw credited his success to more than 10 years of testing corn production techniques; keeping detailed records of what did and did not work, conservation tillage that increased the water-holding capacity of the soil, and choosing hybrids that stood the stress of high fertility and high plant populations.

By the 1970s most McLean County farmers were using the same combine to harvest both corn and soybeans. A special “head” was needed for each crop, but switching between a corn and soybean head was cheaper than buying two separate combines.

Though McLean County farmers had more acreage to harvest, bigger equipment meant the work could be accomplished more quickly.

Between WWII and 2014, the width harvested by soybean combines increased from 6 feet to 30 feet.

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County