Working the Land – 1946 to 2000: Livestock Consolidation

When J.L. Grimes of Towanda decided to build a new corn crib in 1948, it included an adjacent concrete feeding floor and a self-feeder door for his hogs.

Grimes’ crib, with a capacity of 3,300 bushels of corn, was the biggest self-feeder in the area. It eliminated the need to scoop or haul corn to the hogs.

In 1953 John Pratt converted the horse barn on the farm he managed to a dairy barn. The tenant, William Kupferschmid, was willing to learn this new business because, like his landlord, he believed the modern equipment would make the new business profitable.

The new modern pipeline milking system reduced labor, improved cleanliness, and increased yields. With three stalls in the parlor, Kupferschmid was able to milk and feed 20 cows in 45 minutes.

The nursery had a slotted floor and was placed over a cement lined manure pit that Young had dug with a back hoe. He pumped the pit twice a year and spread the manure on his fields. The 24 x 46 foot building included automatic waterers, feeder hoppers that he filled twice a week, and ten farrowing pins.

By the late 1970s intensive livestock farming was becoming the norm. More livestock was produced using less space in order to get the highest output at the lowest cost — a necessary step for those who wanted to stay in business.

In 1977 Tim Benjamin, of rural Bloomington, and his son Timothy J. were ready to dramatically reduce their labor. With 600 to 700 steers to feed a year, they decided it was time to build a specialized building that included an automated feeding system and a slotted floor.

Profit margins for cattle feeders tightened in the early 1970s, and high beef prices resulted in government price controls — a situation that motived local cattle farmers to fight back.

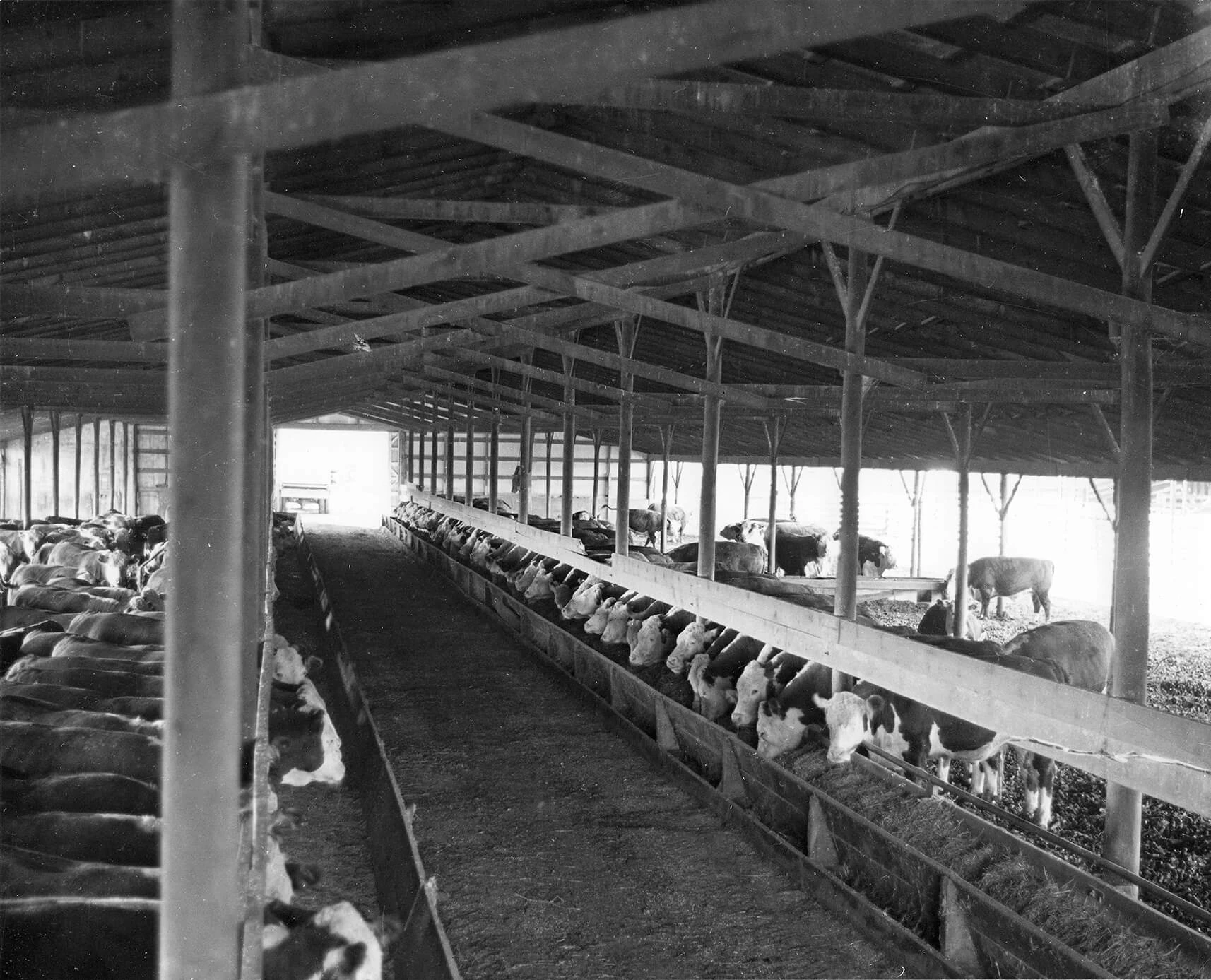

The public was invited to George Pitts’ cattle operation on the Mecherle farm in April 1973.

During the program (pictured here) he and other farmers explained that lower cattle prices would put them out of business, as the cost to produce the cattle would be greater than what they would earn selling them.

In the fall of 1978 Wayne Mohr used computer technology to improve the health of his herd of 100 milk cows.

According to Veterinarians and Nutritionalists Computer Analyzed Rations (VANCAR), most dairymen overfed their herds. Mohr decided to try the VANCAR system, which used herd data and information on the feed fed to the herd to analyze how to best improve their health. Mohr believed the resulting changes had a positive effect on his herd’s health.

“It also cut our feed cost way down. Before we were just guessing on our commercial feed.”

— Wayne Mohr

Bloomington Pantagraph, June 23, 1979

In the 1990s the profit margin for hogs was so low that most McLean County farmers chose to eliminate hog production.

Large scale hog production continued and grew on the Bane family farm in Arrowsmith because they choose to contract with the company that processed and packaged their hogs.

To ensure consistency in the final product the contracting company determined and paid for the feed.

This guaranteed the Banes’ profit margin, which allowed them to invest in the needed equipment.

Pat Bane and his brothers, Phil and Sam, set up the large scale operation in 1995. In 2011 the Bane Family Pork Farm was one of the largest livestock operations in the country. With 2,700 sows, the farm produced about 63,000 feeder hogs per year (1,200 per week).

Some McLean County farmers continued to raise hogs, but in much smaller numbers. Their product was marketed to local and niche markets.

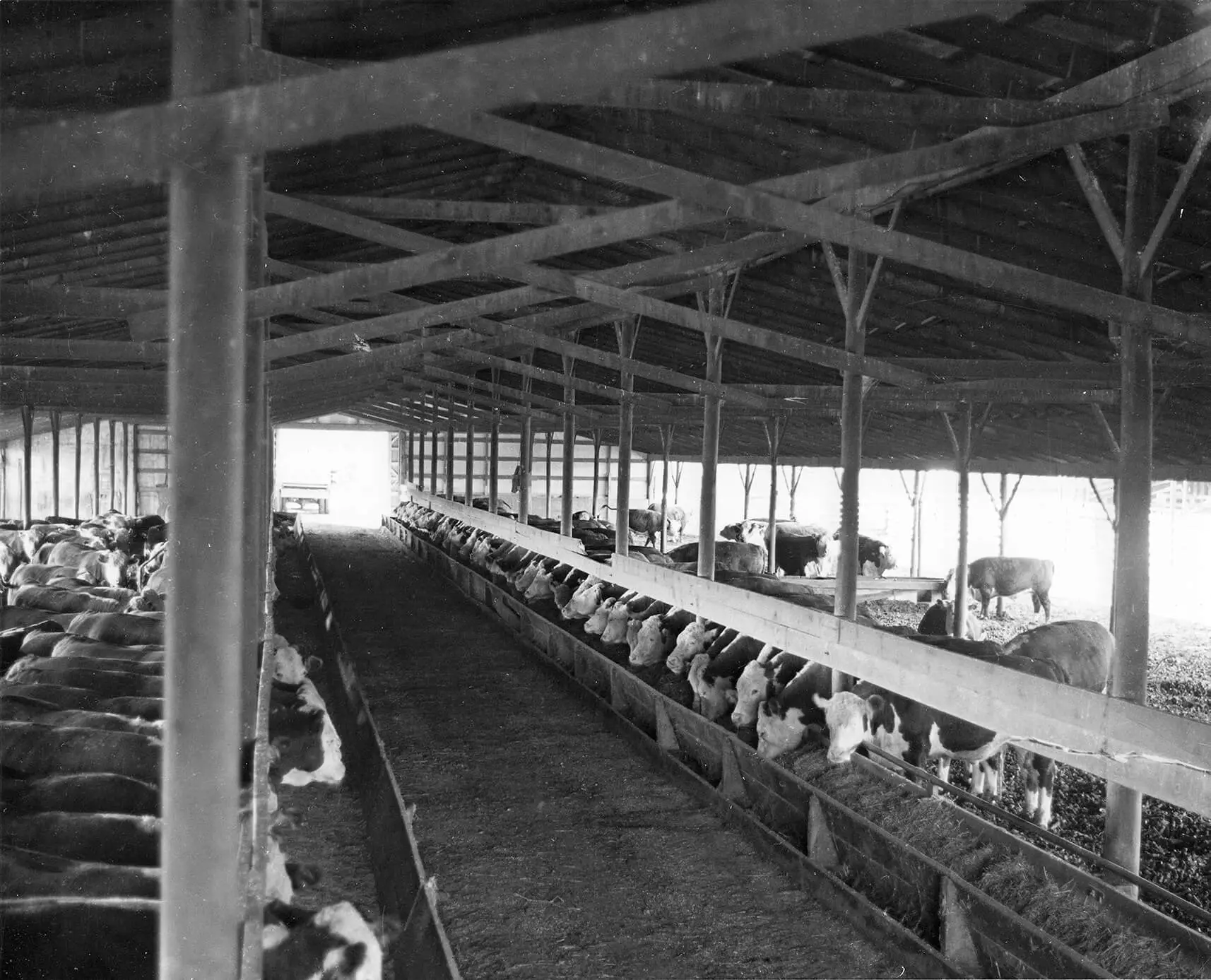

By the 1990s the Funk farm was one of the few still involved in large scale livestock production. Leaders in livestock raising in McLean County since their arrival in the 1820s, their success continued because they used the latest and most innovative technologies available.

As manager of the Funk Trust cattle herd, Dan Koons maximized his land efficiency by confining his cattle to a small area and planting the land he gained with hay crops. His herd was closely monitored to make sure the cattle were fed healthy rations and that incidents of disease were discovered and controlled quickly.

Owned by George Kasbergen, McLean County’s largest dairy operation, Stone Ridge Creamery, contracted with a major dairy company in order to secure Kasbergen’s investment in the specialized facility needed to manage such a large herd.

George Kasbergen’s operation had a herd of 3,000 milk cows when he started operation in 2002.

Despite improved technology, profit margins for dairy farmers continued to fall. By the year 2015 only six McLean County farmers had dairy herds. Some with small herds found niche markets in order to survive.

Normal Township farmer Ray Ropp produced artisan cheeses and ice cream, while Fairbury Township farmer Matt Kilgus bottled his whole milk on the farm. Both sold their products to local and specialty markets.

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County