Getting Crops and Livestock to Market – Marketing Crops and Livestock

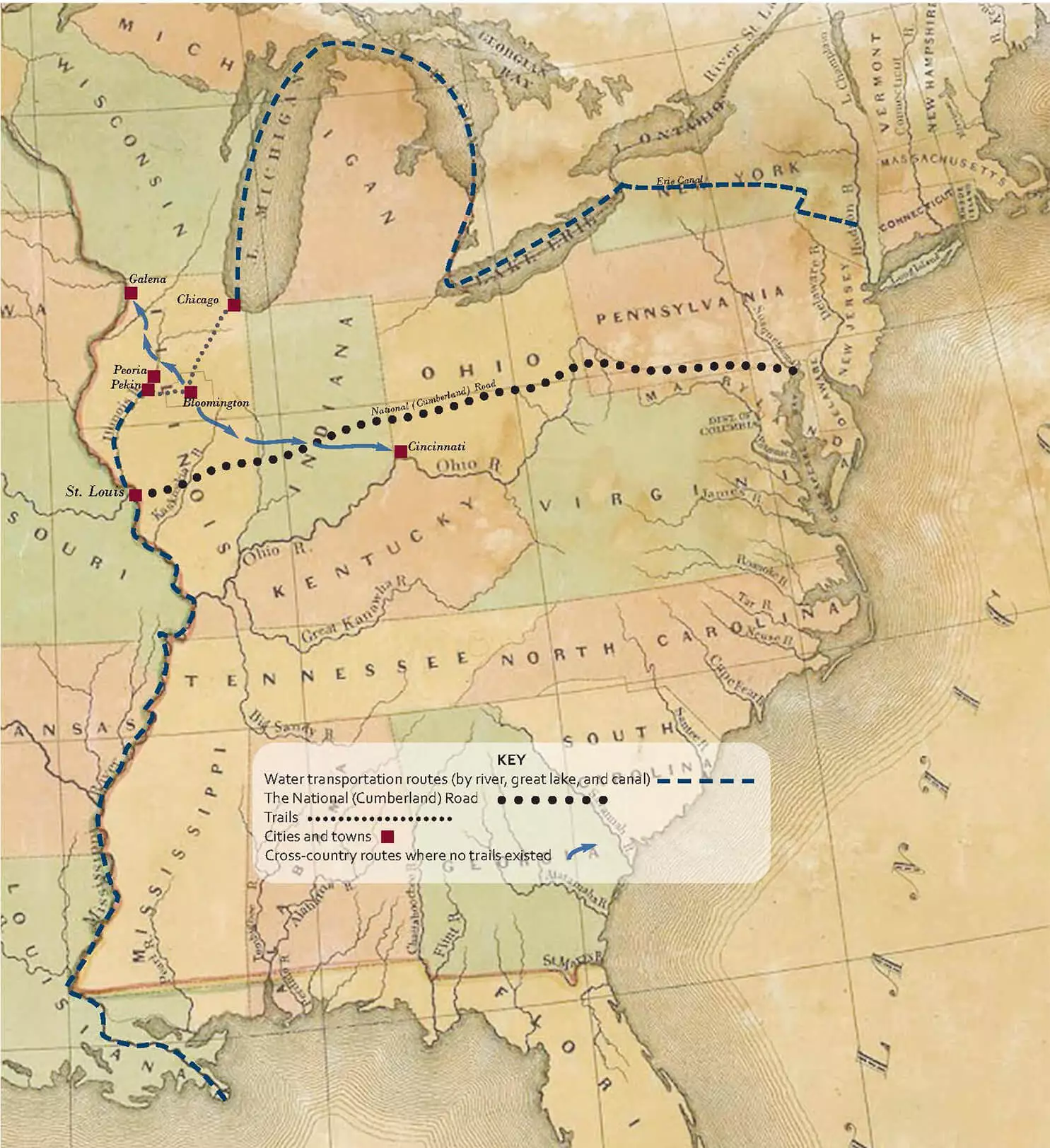

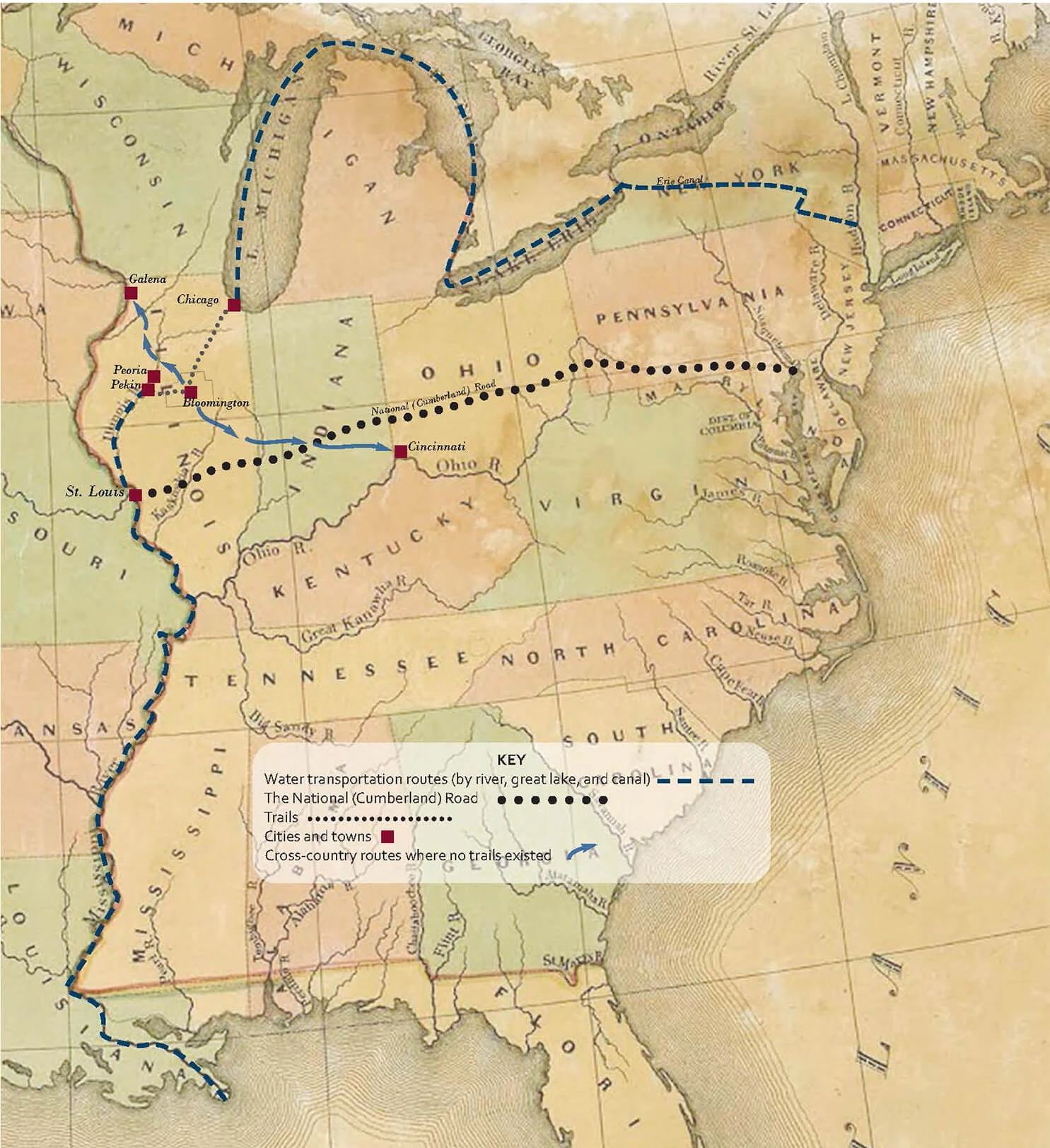

When McLean County was a frontier, most farmers did not generally grow surplus grains or raise large herds of livestock. Those who did faced a major challenge as the nearest markets were in Chicago, Galena, and Cincinnati.

Transporting grain and other frontier commodities, such as maple sugar or honey, could be accomplished by wagon and a trip of 5 to 14 days.

In 1827 R.H. Rutledge of Randolph Grove loaded his surplus grain in a wagon and took it to Fort Clark (now Peoria) on the Illinois River. By 1831 he had determined that markets were better in Chicago and made the longer journey there to sell his grain.

Robert Stubblefield of Funks Grove hauled grain to Pekin and Peoria by wagon until 1842. That year he made the trip to Chicago, earning 90 cents per bushel.

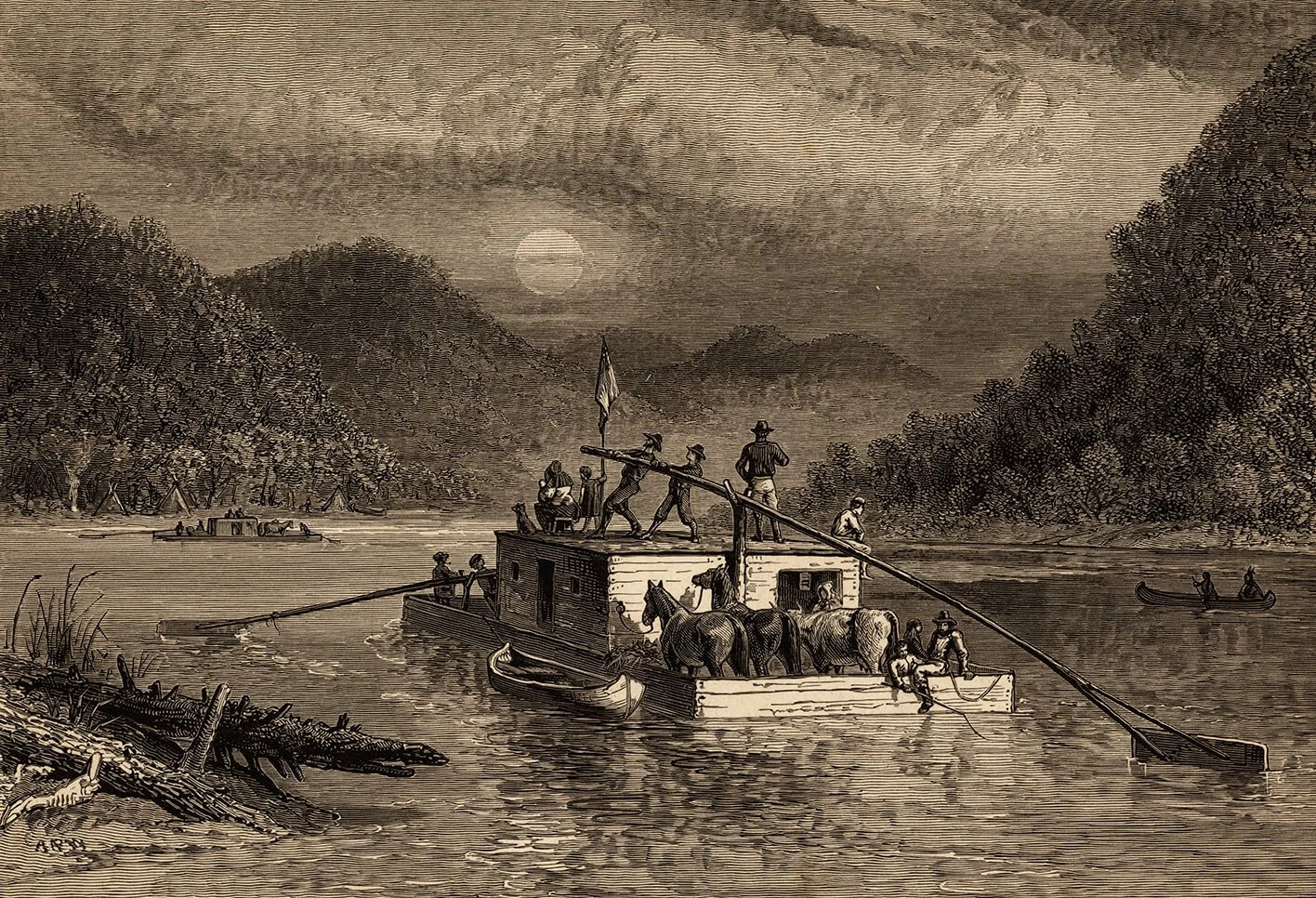

Roads did not exist, and trails were few. But once delivered to a port, such as Pekin, St. Louis, or Chicago, corn and other commodities could be transported by riverboat or barge to distant markets in the south or east.

Surplus grain was mostly fed to livestock so it could be driven “on the hoof” to distant markets.

It took time, determination, and manpower to get a herd to Chicago, Galena, or St. Louis. A successful trip depended on good weather and a cooperative herd. It was always a gamble.

In January of 1836, John Rust drove hogs to Chicago for Isaac Funk. The temperature dropped, and heavy snow began shortly after they started. More than six inches of snow fell. At Wolf Grove they were forced to fasten a log to the rear axle of a wagon to break the way.

At the Kankakee River the rapids were partly frozen. They cleared the ice, but the hogs refused to go into the water. The drovers built parallel rail fences, and forced the hogs between them and into the river. Both hogs and humans made it to Chicago, but just barely.

A trip to city hubs did not guarantee good prices.

Dissatisfied with pork prices from their local meat processor, local farmers pooled their efforts and drove their pigs to Chicago.

After much effort to get their hogs to Chicago they earned about a dollar per head for their hogs — a good price, even after the expense of the journey and time away from the farm.

The local processor, Depew & Foster, responded by paying higher prices to the Blooming Grove farmers. By 1850 the company was bankrupt and local farmers had no choice but to drive their produce to Chicago or other distant markets.

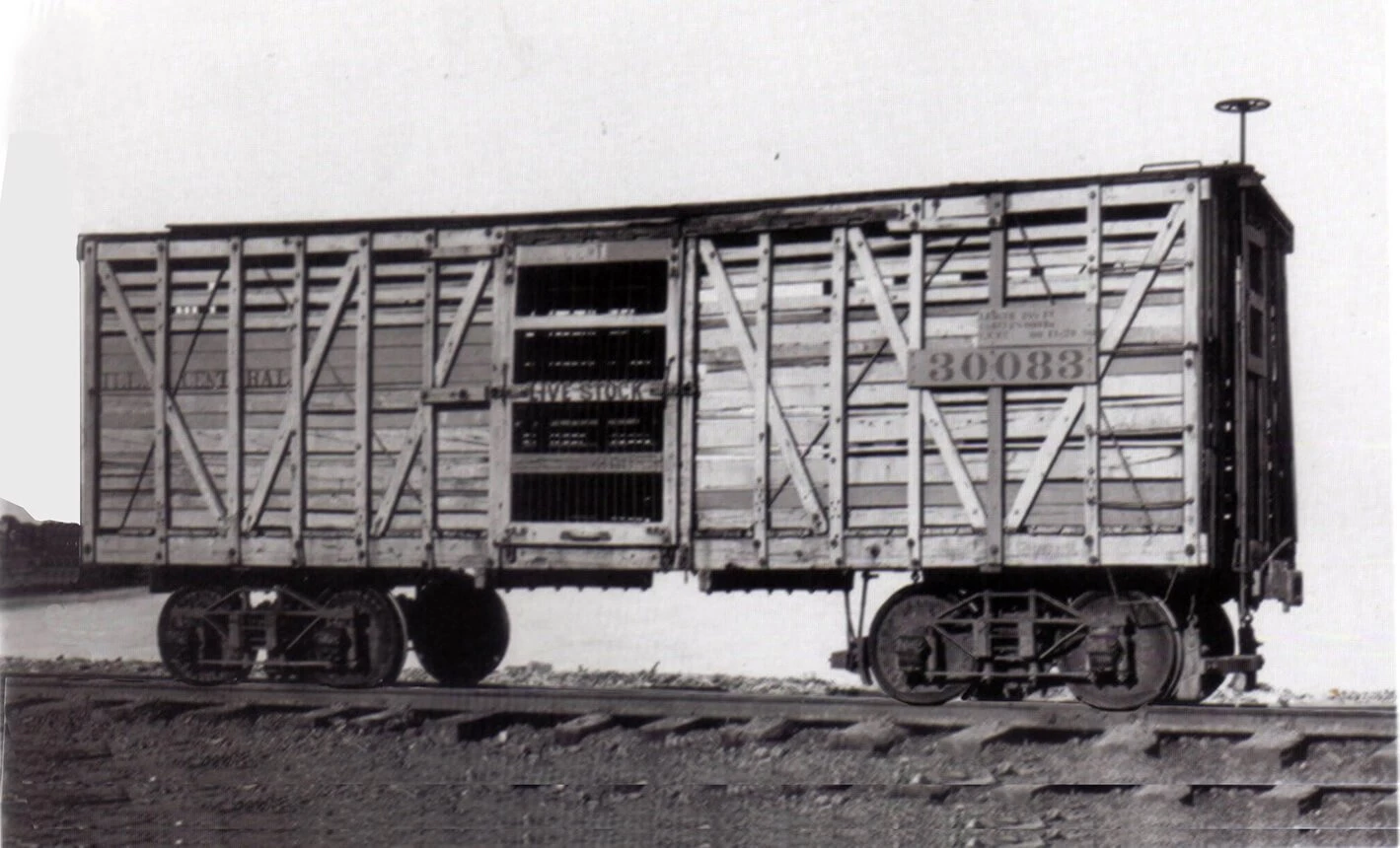

Once the railroad arrived, farmers had the option of shipping surplus grain and livestock to markets in Chicago, St. Louis, or beyond. But not all chose to.

With rail transportation available, more McLean County farmers chose to produce livestock in greater numbers.

If managed properly, profits were much higher for those who raised greater numbers of feeder cattle and hogs. The trick was earning enough profit to offset the cost of rail transportation.

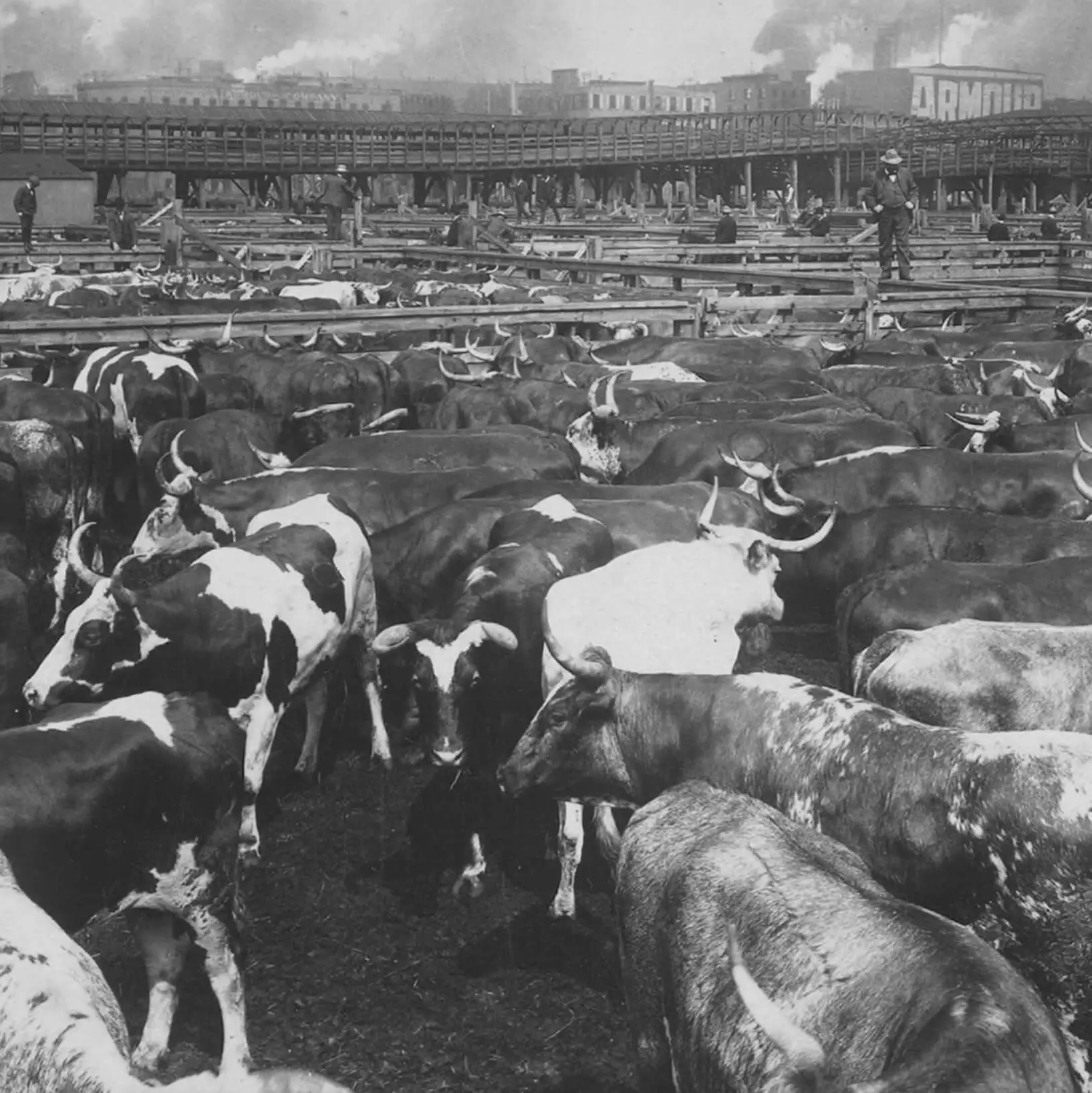

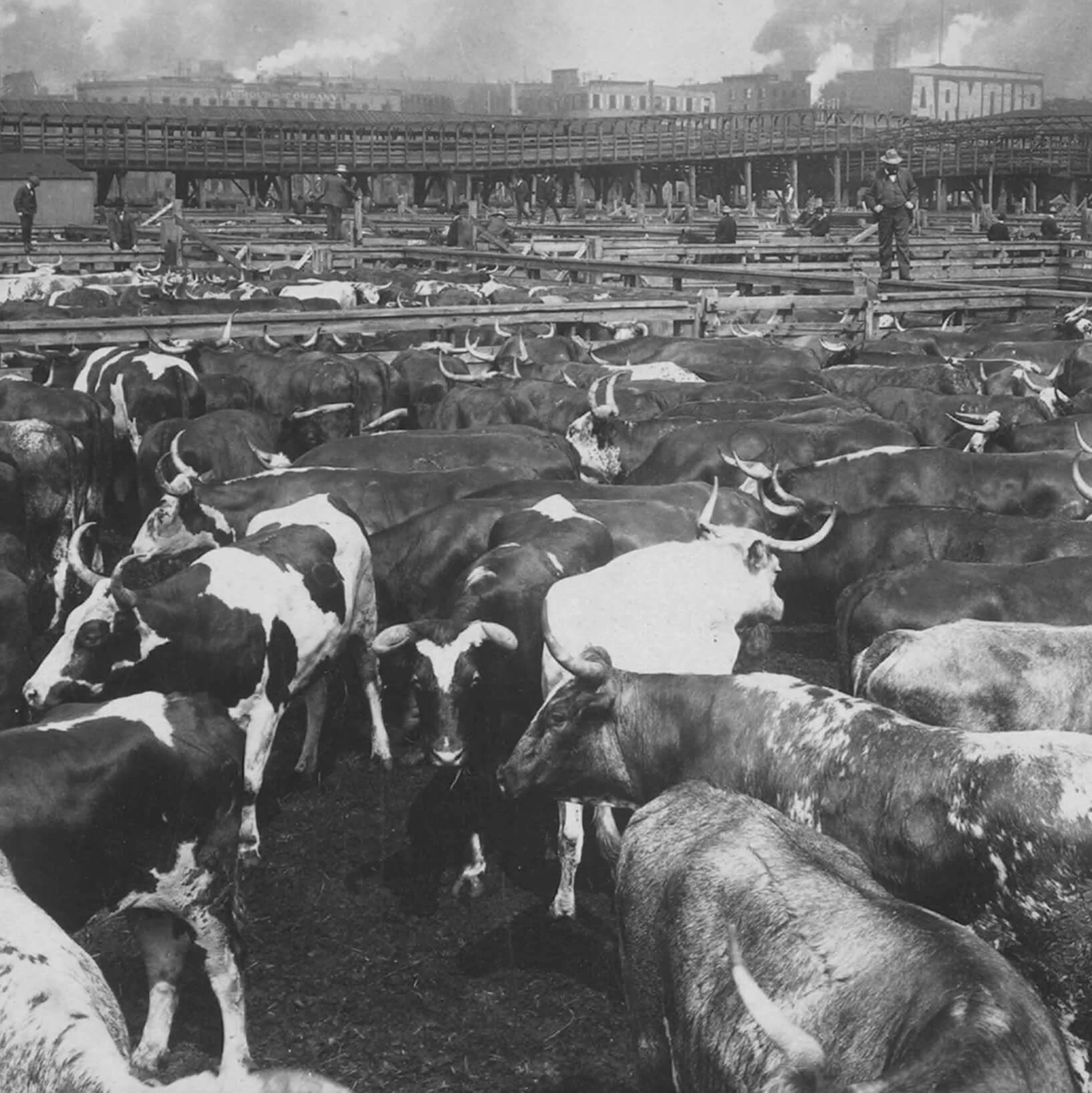

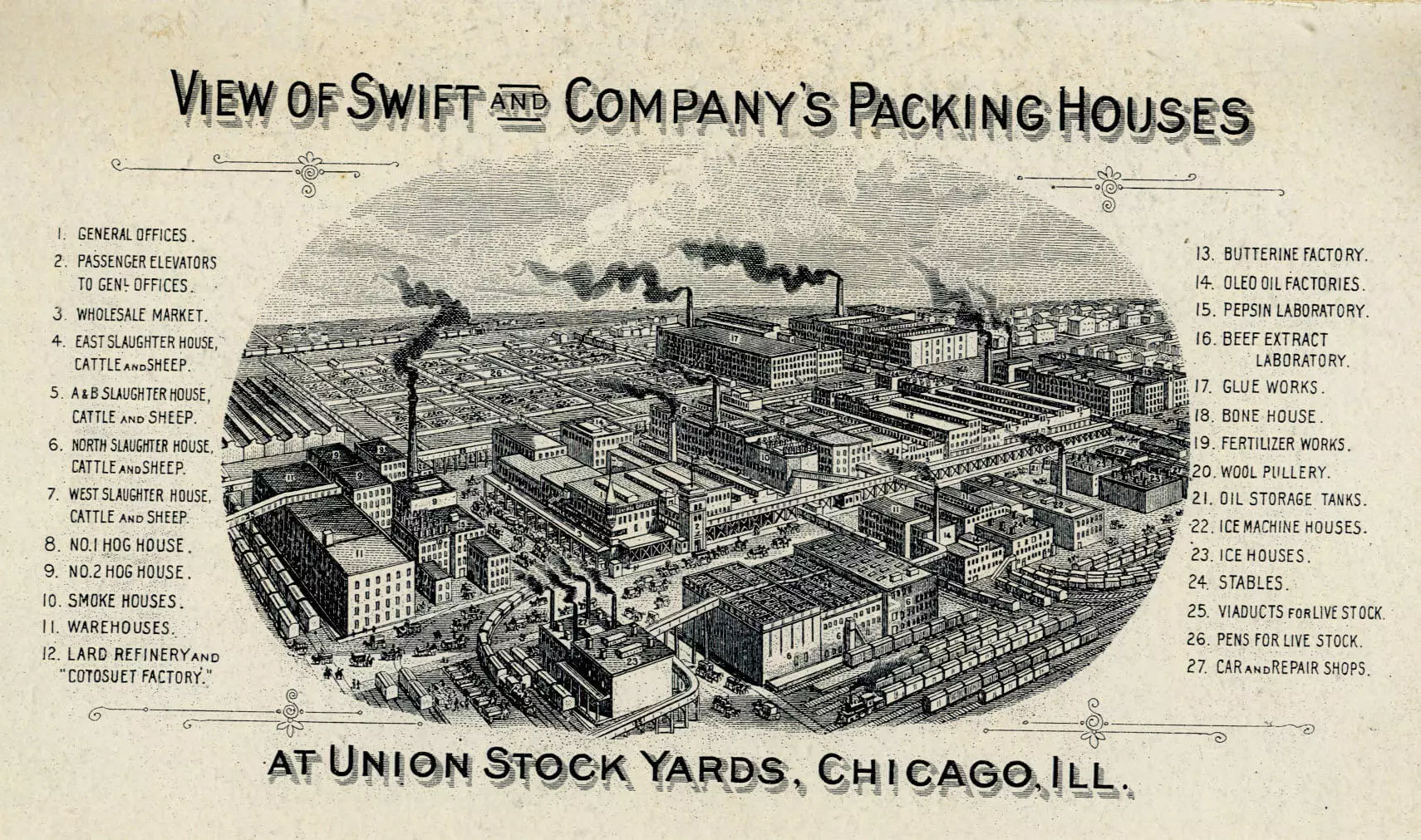

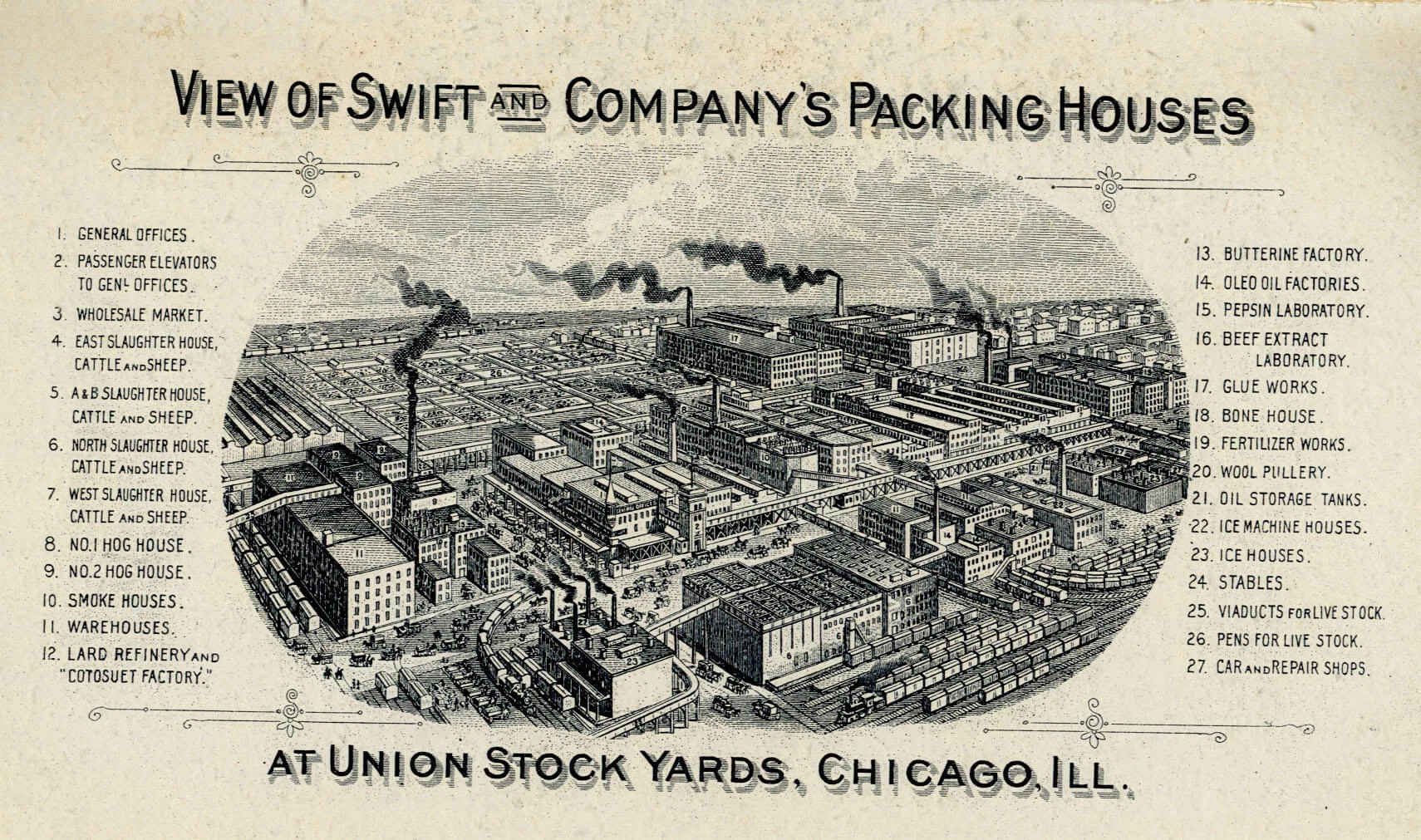

In 1865 the Chicago Union Stock Yards were established in order to provide a larger, more centralized, and efficient system for stock delivery and processing. McLean County livestock farmer Isaac Funk was one of its founding members.

According to Bloomington farmer Simon Moon, “Nine railways abandoned separate stockyards to create the Chicago Union Stock Yards to furnish day and night cash marketing service.”

Some sold their livestock to a middleman so they did not have to manage the shipping.

In the winter of 1878 the Newcomb Brothers of Saybrook purchased nearly 200 hogs from area farmers paying about $3.40 per hundred (lbs. of hog). They shipped these hogs to Chicago and grossed an average of $4.25 per hundred.

After subtracting the cost of shipping, the brothers still made a decent profit.

McLean County farmers did not have to go far to buy or sell their horses, as Bloomington was an important regional market for the sale of locally bred horses, as well as horses imported from abroad.

Some of these horses were purchased in the eastern United States or imported from Europe, then shipped by rail to Bloomington.

When W.M. Van Schoick opened the Bloomington Pork Packing Company in 1873, many area farmers chose to sell their hogs to his company.

The prices they received were less than Chicago prices, but sellers saved the cost and risk of shipping the livestock by rail.

In 1882 the company purchased and butchered 12,000 hogs from Central Illinois farmers.

In the early 1900s some area farmers believed the middle man was taking too much and took action by trying to market their livestock more directly.

Directors of the Breeders Sale Company in Bloomington decided to build a big sale barn and pavilion in Bloomington for selling horses, cattle, and hogs. They hoped to make it the central stock market of the state.

Bloomington’s Coliseum was constructed in 1909 and the first sale was held that September. The successful sale was followed by many more.

The completion of the Illinois Boulevard between Chicago and Bloomington in 1923, a two-lane paved road for heavy traffic, meant that livestock and grain no longer had to be transported via the railroad.

It was several years before trucks gained the size needed to make transportation of livestock economical, by then the boulevard had become part of U.S. Route 66.

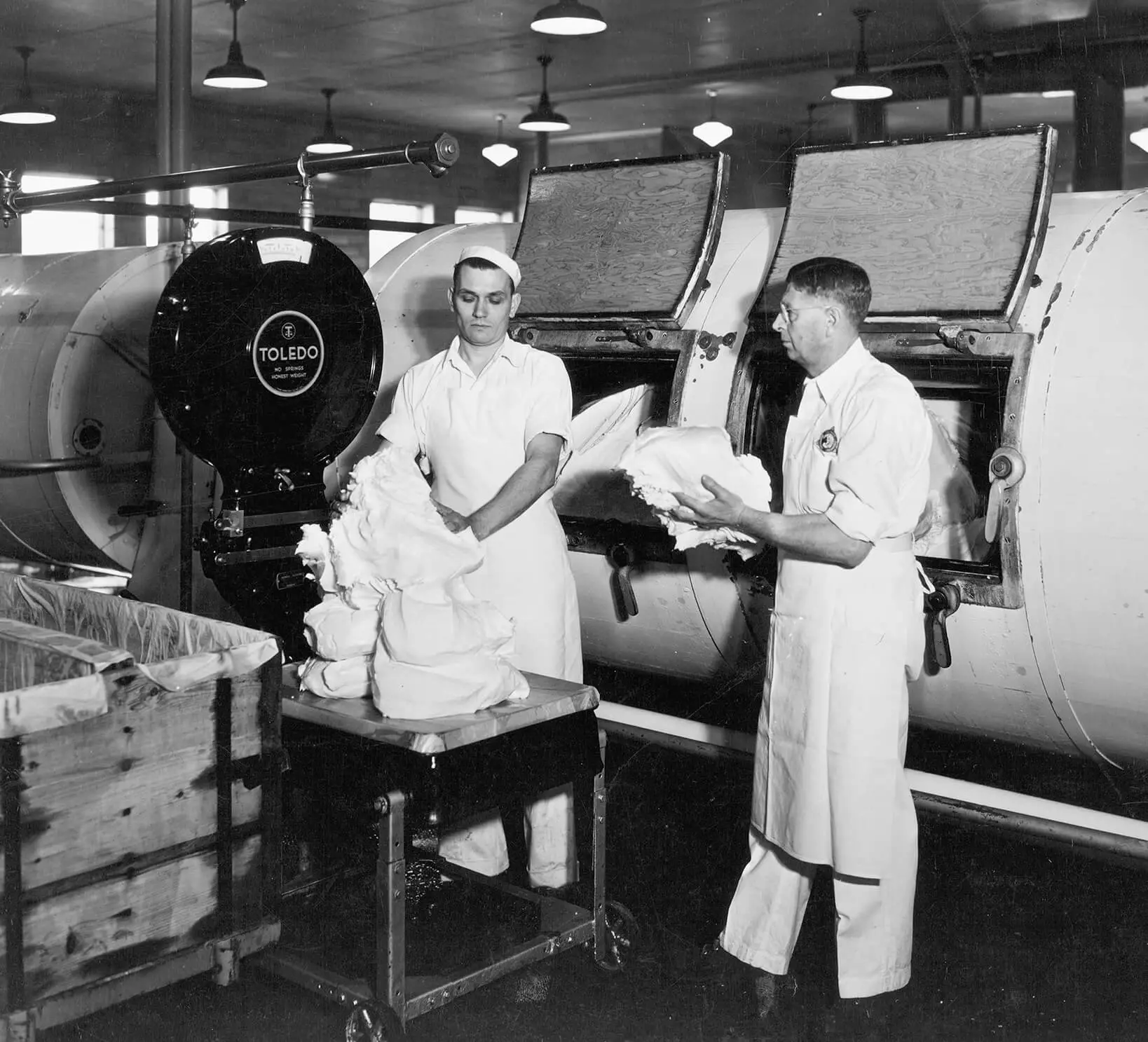

In 1927 McLean County milk producers organized an association that enabled them to pool their farm cream and negotiate a better market price.

Soon afterwards they had a contract with Bloomington’s Snow & Palmer Dairy.

In 1929 work began to build a facility to handle cream and milk.

In 1933, with loans from the McLean County Farm Bureau, the Prairie Farms Creamery opened its doors. It was one of 12 cooperative creameries accross the state. At first the creamery processed only butter. After WWII dry milk was added. In 1957 the plant was sold to the Pure Milk Association, of northeastern Illinois. Declining local milk production resulted in its closure in 1961.

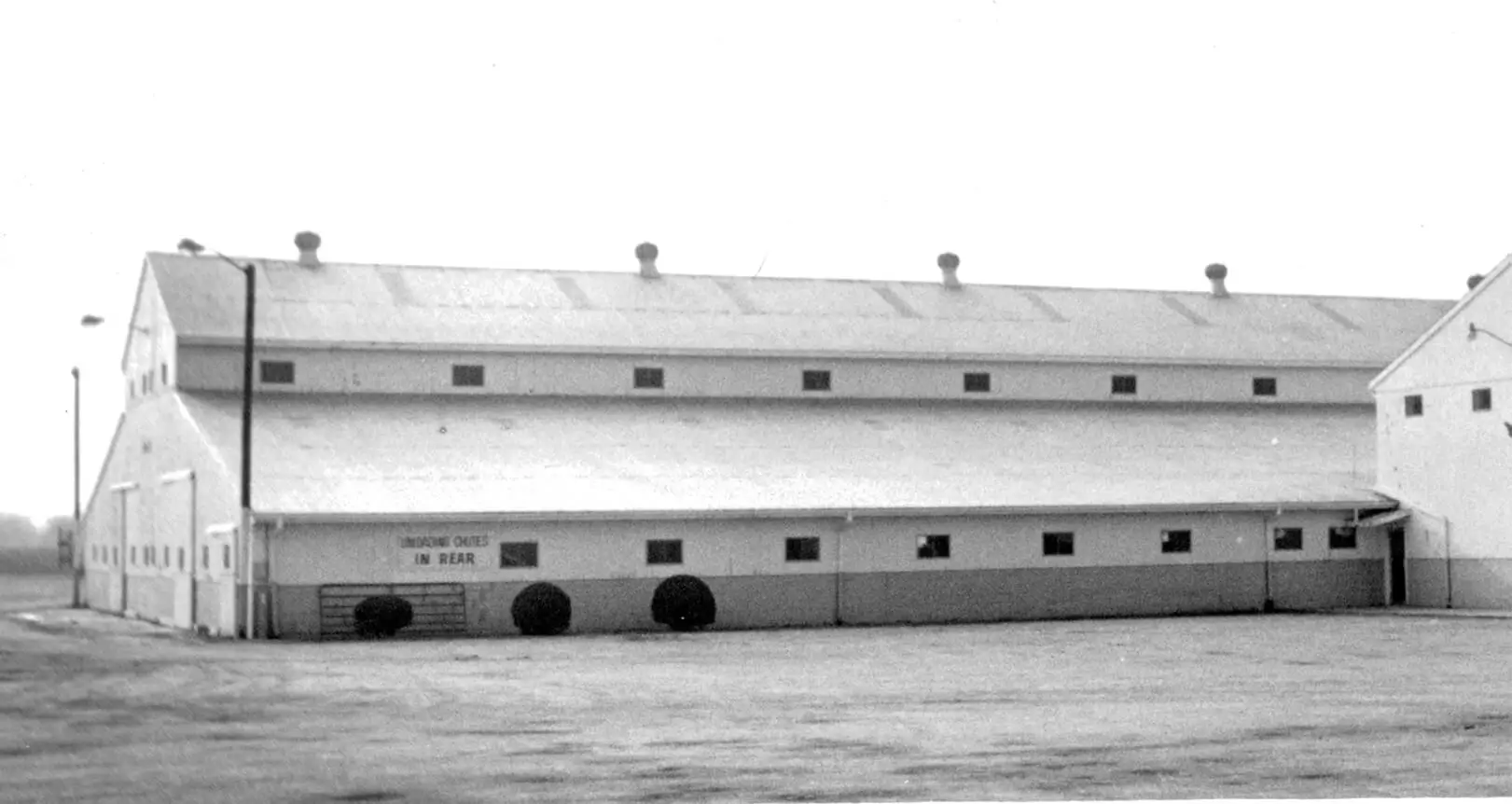

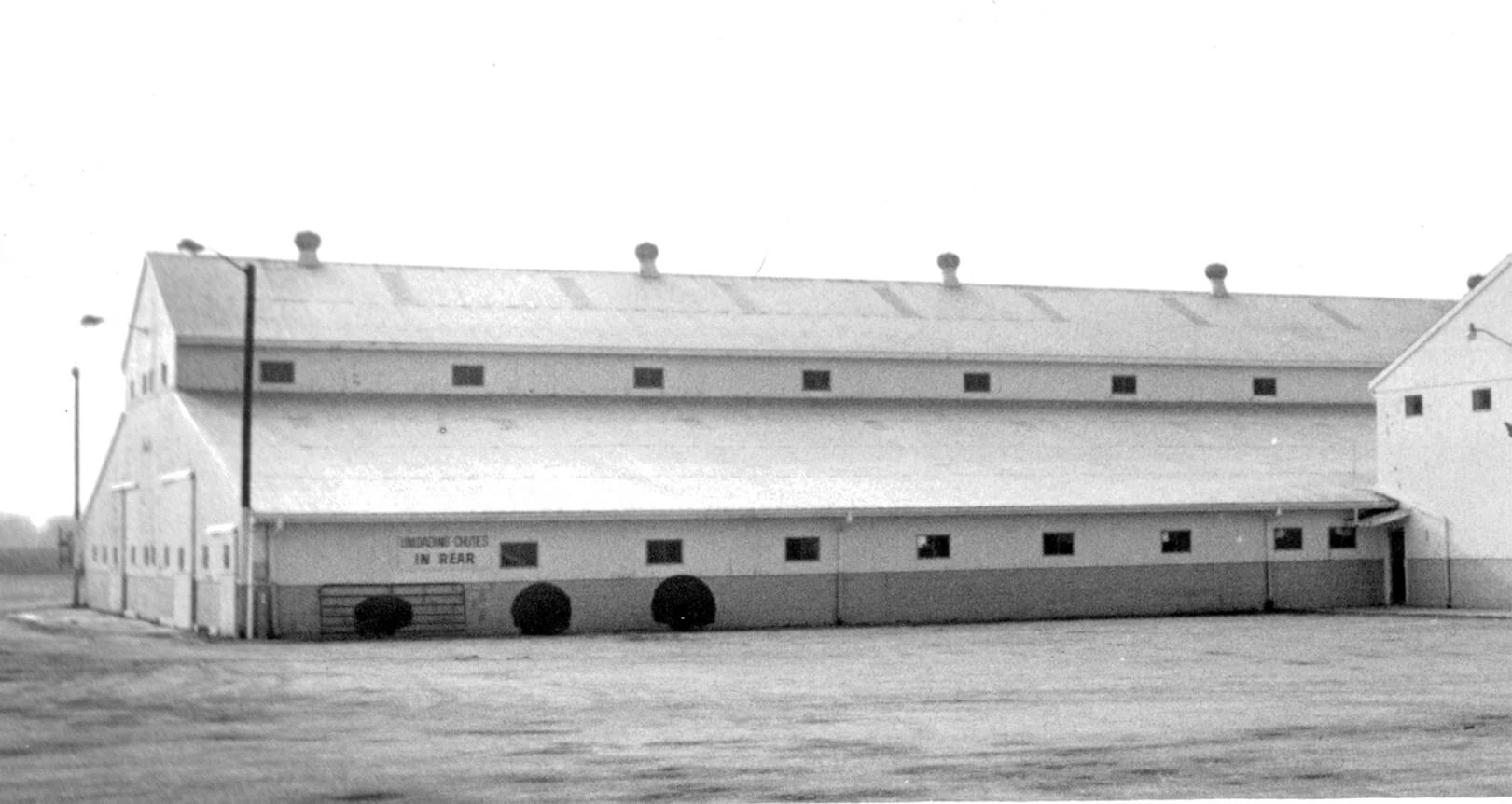

The Bloomington Stock Yard (later Producers Stockyards), located on Lafayette Street, was a centralized McLean County location for selling livestock. The stockyard also trucked livestock to regional markets. Founded in 1933 the stockyard merged with the Interstate Producer’s Livestock Association (IPLA) in 1969. At the time IPLA served Illinois, Iowa, and Missouri and was the nations largest livestock marketing cooperative.

After WWII most farmers sold their hogs and cattle to local livestock companies that then sold the animals to regional meat packers.

Meat packers preferred this approach because the livestock companies grouped animals by type and size and delivered their purchases.

Some McLean County farmers trucked their livestock to the Peoria Union Stock Yards.

On November 2, 1983 the Peoria Union Stock Yards sold 750 feeder pigs that regional farmers had trucked in.

By 2010 nearly all large scale livestock farmers in McLean County had direct contracts with a processor. These contracts specified feed, delivery date, and price, and eliminated the middle market.

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County