My name is Aidan Coyne, a history education major from ISU interning in the Library & Archives with Katie Sutrina-Haney and Bill Kemp. This semester, I’m working on organizing and managing the Museum’s vast physical audio collection. You can typically find me here every morning Monday through Friday – partly due to my otherwise hectic schedule, and mostly due to the fact that I love it here.

The Museum’s collection ranges from vinyl, CDs, and cassettes, to reel tapes and even a flexi-disc. The actual contents themselves are more intriguing; Adlai E. Stevenson II’s speeches alone, as anyone familiar with Bloomington might expect, comprise two entire boxes. Although, in my opinion, there are at least a few things here more intriguing than that. This is including, but not limited to: Joe Dowell’s collection, two local artists sampled by rappers Kendrick Lamar and Travis Scott, Chris Young’s “Downstate Sounds,” and non-musical media like Pepsi’s “Your Man In Service” promotion from World War II.

I’ve turned the collection inside out, dumped everything on the table (not literally – I promise nothing has been broken), and arduously organized each piece of media by updating the former finding aid. But that’s just a figurative way of putting it to make it sound more difficult than it was. Much – but not necessarily most – of the collection wasn’t clearly categorized when I first arrived here and was starting to pile up in a somewhat disordered fashion. So, after freaking out about organizing principles, dates, genres, and the alphabet for a while, I got to work sorting through everything in a way that will, hopefully, make sense to those who wish to access the collection in the future. I’ve been working on cleaning every record as of recently. Typically, political and spoken word records need very little cleaning – I suppose the likes of “Watergate Comedy Hour” do not appeal to everybody quite like an old jazz record does. The act of cleaning a record is an almost emotional exercise – frustration, disgust, satisfaction, and joy are all different emotions that pop up from a record’s first to thirty-third and a third rotation of cleaning. Again, though, this is probably not a universal experience. However, this is really stuff that I love to do – organizing, cleaning, categorizing, and contextualizing music – that I had scorned the world for not making a full-time occupation as a young child. Well, I’m still not sure that it is, but it’s at least an internship position!

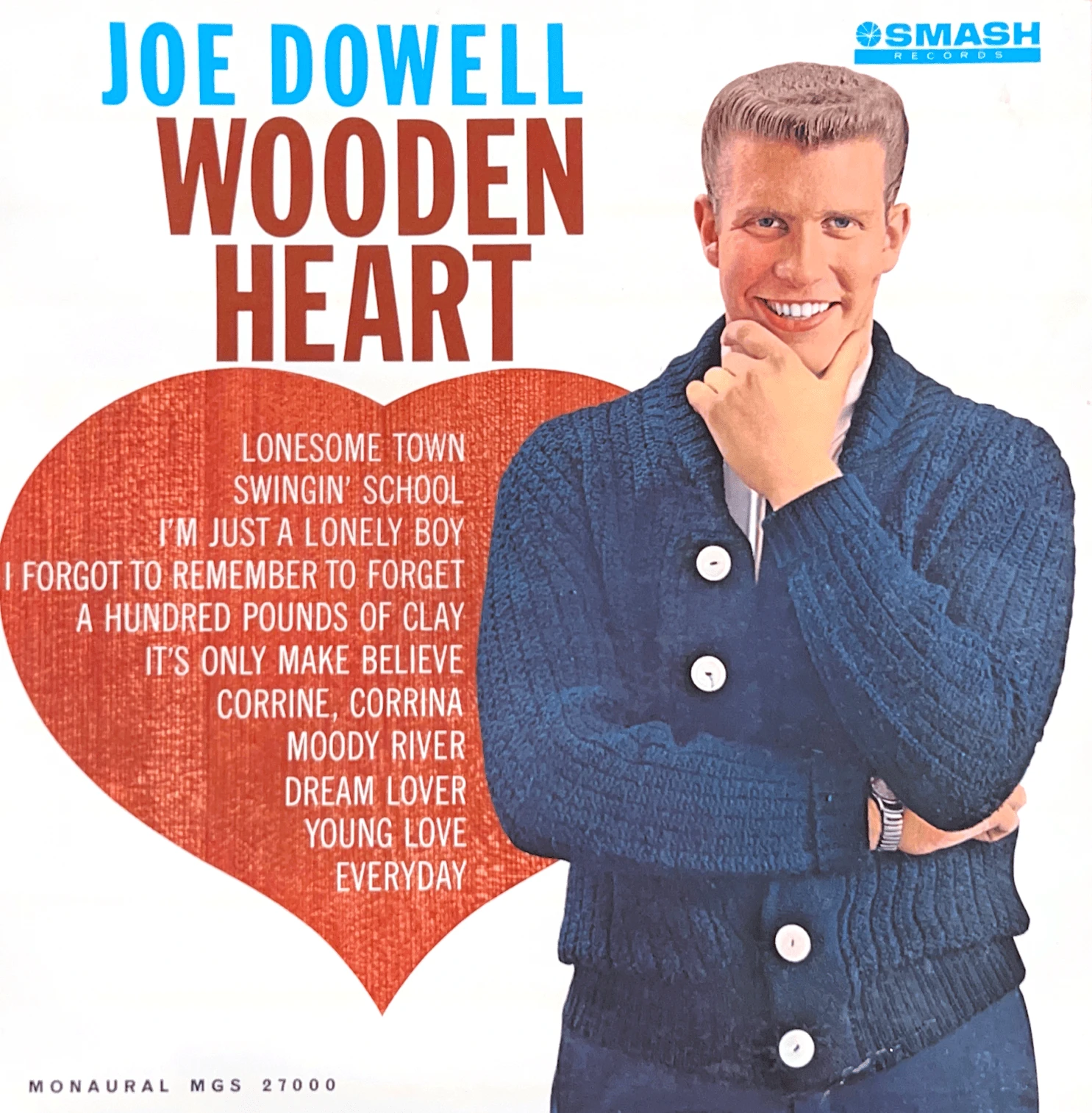

Anyone finding themselves in front of the collection would struggle to not find anything of interest. Joe Dowell, an obligatory mention, is the most commercially successful artist to hail from Bloomington. His song – or rather, Elvis’ song, or rather, Elvis' rendition of an old German folk song – was the first and only (for now!) single from an artist in Bloomington to top the Billboard 100.

See, when Elvis came out with “Wooden Heart” in 1960 for the movie G.I Blues, his label didn’t believe the American public was quite ready to listen to German on the radio yet. Dowell, however, released his own cover in 1961, where it shot up and stayed at number one for two weeks. In the U.K., Elvis’ version topped the charts for 6 weeks; in the U.S., released finally in 1964 as the B-side to “Blue Christmas,” it peaked at 107. Dowell went to war, then to the University of Illinois, and then back home to continue his career. Despite never quite becoming a national household name, his story is really fascinating – have any other artists out-charted Elvis as his contemporary? His name lives on as a Bloomington icon, and his collection in the museum is unrivaled by any other artist (or politician).

Okay, I might’ve lost some younger readers with that one, but how about this: Bloomington has a connection to the Kendrick Lamar and Drake feud of 2024. I actually found this out while listening to local group Andrew Wartts and the Gospel Storyteller’s 1982 “There is a God Somewhere,” which is, by all accounts, a fantastic gospel funk album (if you’re into that kind of thing – and even then, normally I’m not). Several comments on YouTube were referencing rapper Kendrick Lamar, and I began to smell a McLean County connection that, like any potential McLean County connection, could not be ignored. Lo and behold, Lamar’s “Meet the Grahams” samples “Can You Say Yeah?”, track four off of the album. The only possible thing that could top this connection would be a performance of the song by Lamar in the museum’s courtroom, which I am waiting to hear back from his team about.

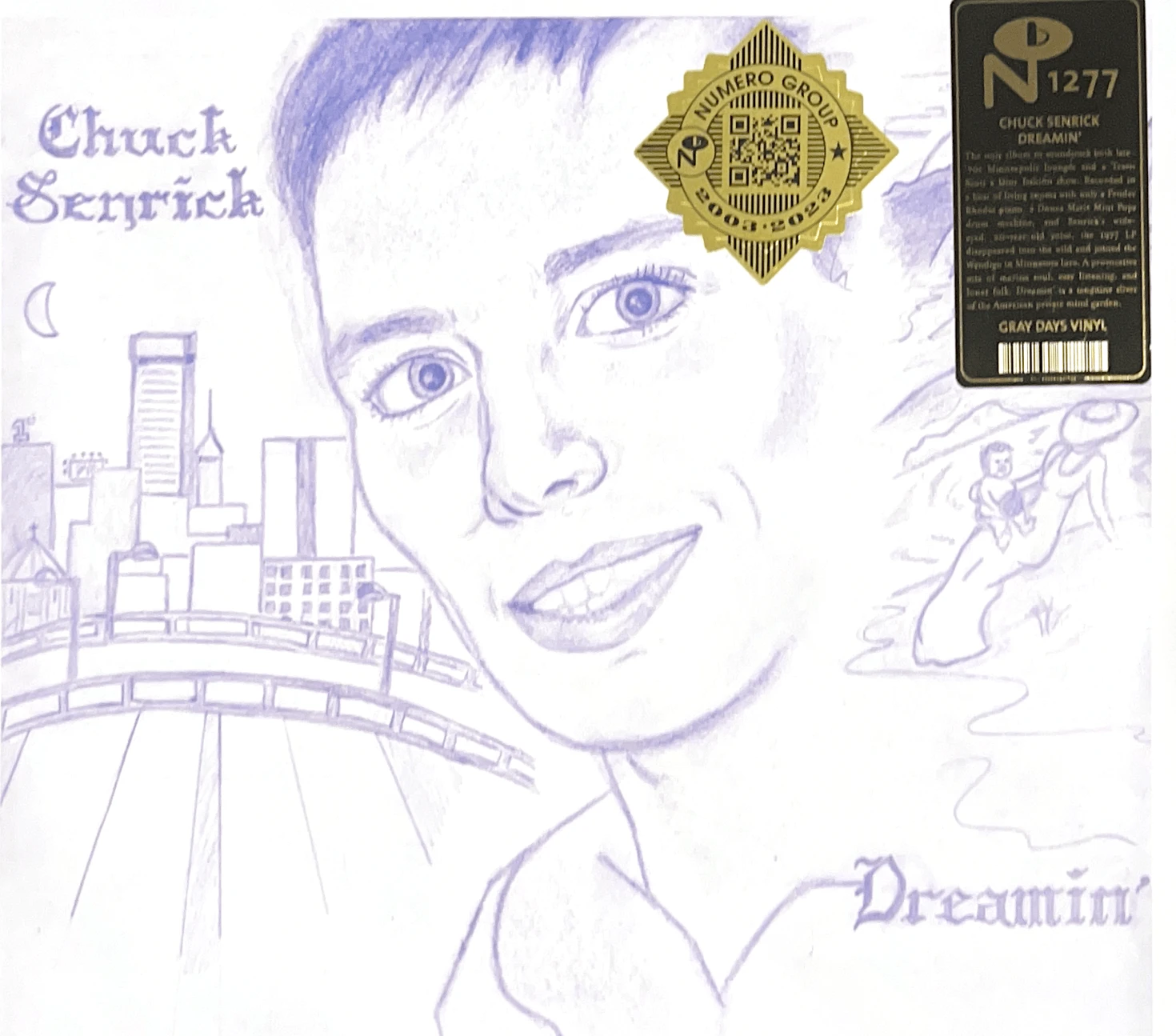

Here’s another hip-hop connection – Travis Scott’s “Lost Forever,” featured on his Grammy-nominated album Utopia. The sample wading through the track’s beat is Chuck Senrick’s “Don’t Be So Nice,” a mellow piano tune from the Minneapolis-born pianist who has played piano at Jim’s Steakhouse since the 1980s. Remarkably, the copy we hold in the collection is a repressing from the Chicago based Numero Group, who handle lost or rare recordings and release them with fancy sleeves, artwork, and liner notes. More remarkable is the fact that they wrote an entire biography about Senrick without mentioning his 40+ year Bloomington connection – shame!

Researching this type of thing really isn’t always as simple as searching through YouTube comments, though. Even then, trying to contextualize a local artist isn’t something you can always do scrolling through local papers, writeups by the museum’s own Bill Kemp, Discogs, and numerous blogs (which is often how I’ve managed much of the material). For that reason, my work here is quite indebted to Illinois State University librarian Chris Young, who has been willing to discuss his former work here and whose vast local connections have served as an invaluable resource. Young’s radio show and corresponding website, Downstate Sounds, are both worthy rabbit holes in their own right, and you can conveniently find the former in its entirety sitting in the museum’s CD collection.

Prior to moving to Bloomington-Normal, the only band I had actually known from here was Impetigo, a comparably big band in the comparably niche genre that is grindcore. I had no choice but to honor them by purchasing and donating a copy of 1990’s “Ultimo Mondo Cannibale” to pay my respects. However, the music of McLean County is varied and sprawling and cannot simply be defined by genre or vernacular. There are folk musicians, such as Marita Brake and Jerry Meiss; Big band artists like Al Pierson; Mamas and the Papas-esque psych-rock like Spanky and Our Gang; and a plethora of experimental music thanks to the likes of Stefen Robinson’s Yea Big.

I’ll end this post off by mentioning one of my favorite non-musical items in the collection, that being a voice recording of Willard Johnson, whose voice was recorded at Camp Plauche, Louisiana, during World War II. It was donated by Lynne Fazzini, Johnson’s daughter. The record comes as part of a promotion that Pepsi did during the war called “Your Man in Service,” in which they set up recording booths for soldiers to record and send out a message to their loved ones at home. After cleaning up and giving the old 45 a spin, Johnson’s voice came through the crackle as he delivered a message to his wife. I found it so fascinating that such a thing even existed in the first place: part heartfelt message, part advertisement, full historical document all in its own right.

Listen to Willard's message here:

A major thing I’ve learned in my time here is that documenting physical audio media is a truly significant part of a museum’s archival mission. On one level, we have so much to learn from the styles and tastes existing in and spawning from our local area, but on another, we gain so much from immersing ourselves in the context of the past, as Willard Johnson’s “Your Man in Service” entry does so well. I thank everyone at the museum for giving me such a fantastic opportunity.