Railroad Workers Were Still in Demand

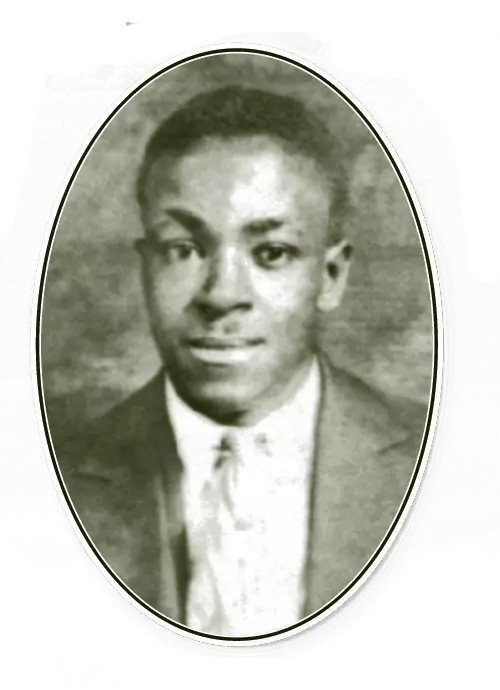

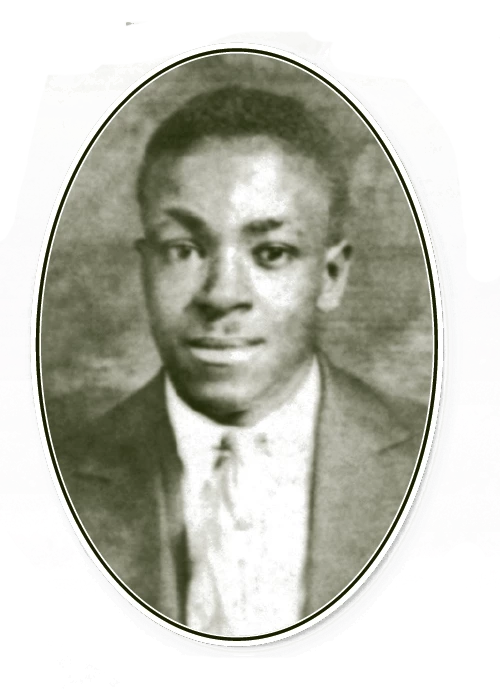

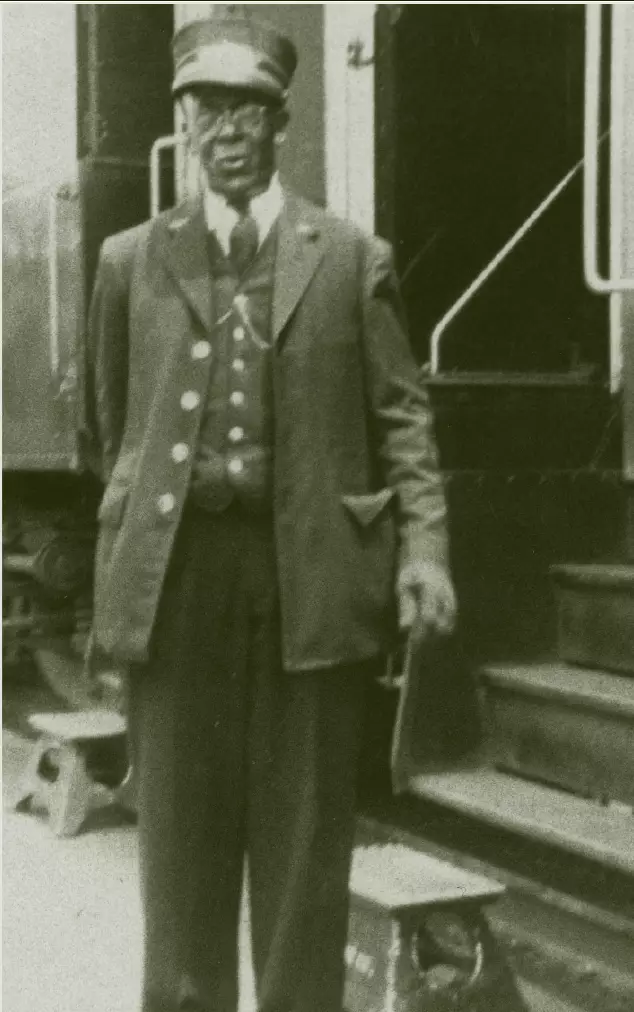

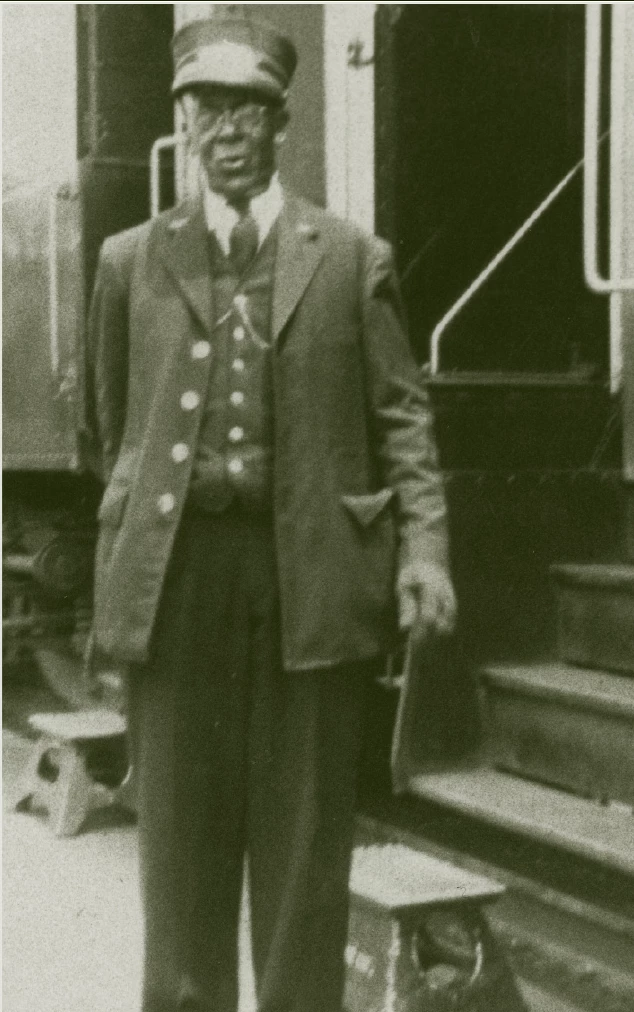

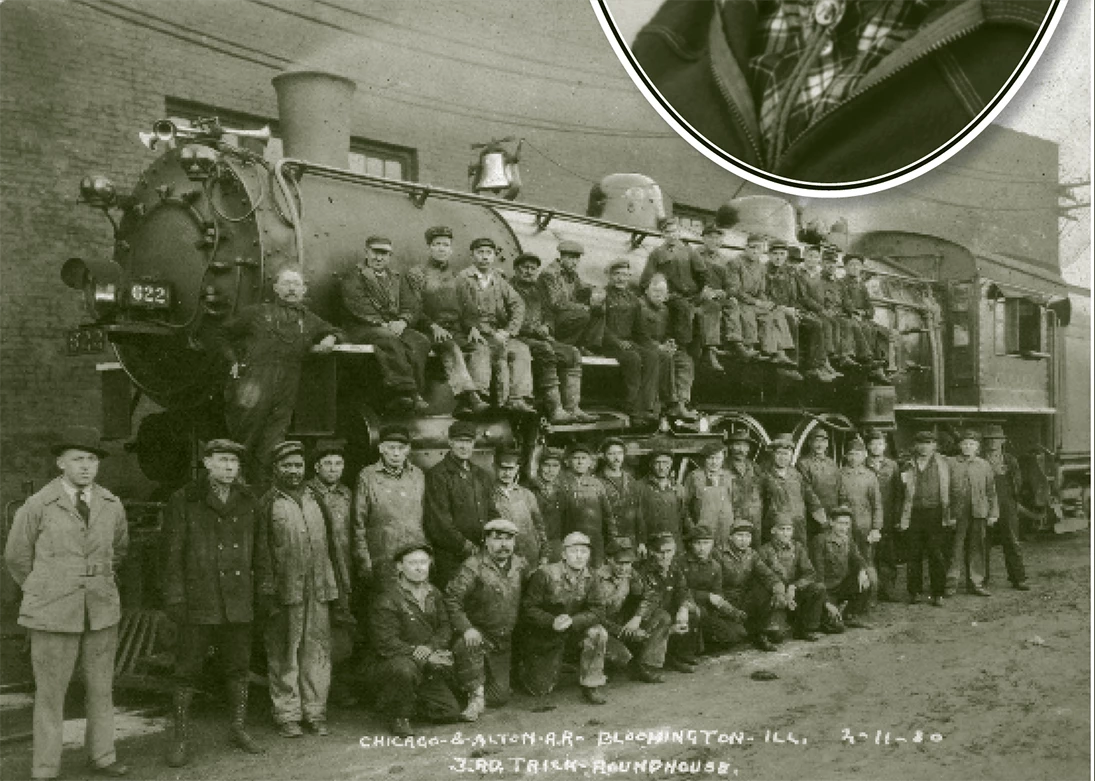

Despite the rising popularity of auto travel, rail transportation remained prominent. Laborers and skilled crafts workers at McLean County's largest employer, the Chicago & Alton Railroad shops, were still needed. By the 1910s, more dealers were selling cars and more people were driving. Gas stations opened, roads were improved, and auto mechanics stepped up to make repairs. How we got to work and where we worked changed dramatically.Featuring:Carl Samuels, (1906 – 2005), African American, C&A scrap laborerJohn Whittington, (1865 – 1941), C&A painterJoseph D. Penn, (1898 – 1987), C&A superintendentCarl Samuels (1906-2005) was a Bloomington native who began work at the Chicago & Alton shops in 1922.

Carl worked on the scrap gang dismantling old railcars, separating wood from metal, and collecting scraps from the various departments in the shops. He also worked the coaling tower, where he shoveled coal into a hopper that loaded the locomotive tender (the car behind the locomotive).

Carl hoped to get a better job at the C&A RR.

What kind of jobs do you think were available to African Americans working for the railroad in the 1920s?

African Americans like Carl were excluded from shop apprenticeships and train operating crew positions. The only jobs they were hired for included laborer, dining car server, or passenger train porter.

When the Great Depression began, Carl’s job on the scrap gang was given to a white man. But as the Depression ended, Carl began to fill in for porters who were sick or on vacation.

As a porter Carl assisted the train conductor by carrying luggage and tending to passenger needs. Carl really liked this job, especially when kids were on board.

What he did not like was that all other workers were paid “deadhead” time (non-working time spent on the train getting to the start point), while African Americans were not. And his rate of $4 per trip to Chicago and back, plus tips, was less than what other crew members earned.

Because he was a replacement porter, Carl also worked as a janitor at ISU, or shined shoes at a downtown barber shop in order to survive.

In 1937 an African American led union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, was organized and won a contract with the Pullman Company. When the union began to include train porters, Carl joined and his pay improved.

Carl retired from railroad work in 1962, but continued to work as a janitor at ISU until 1972.

“If it wasn't for the union, I wouldn't have gotten the little bit of change I did get.”

— Carl Samuels

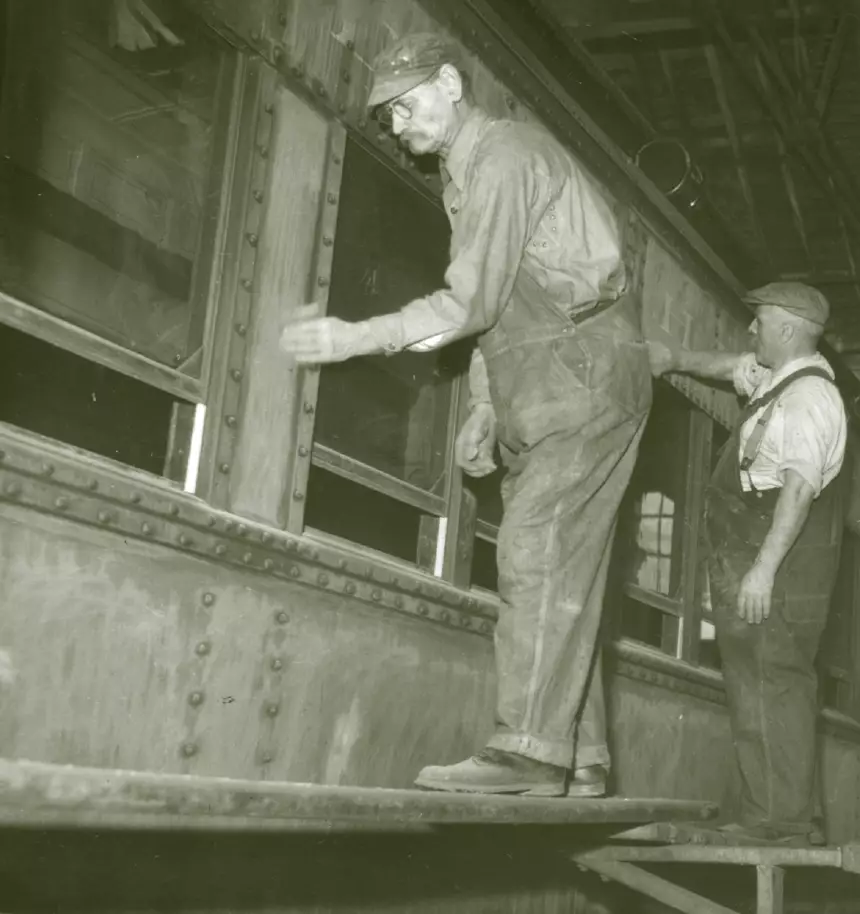

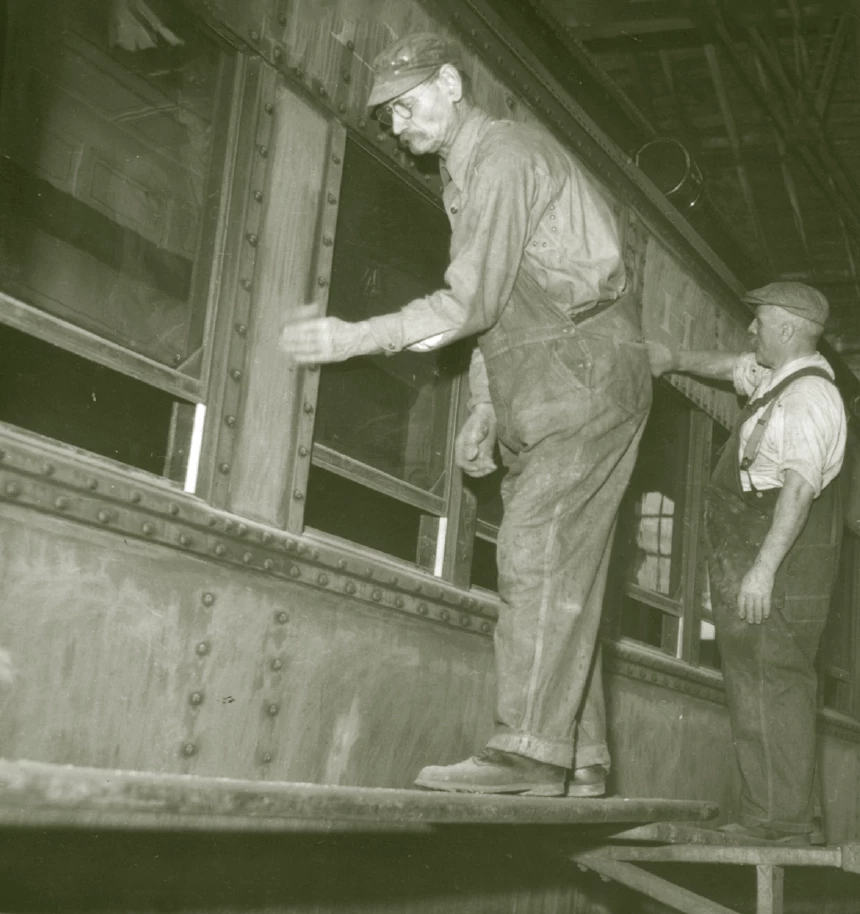

John Whittington (1865-1941) came from the Fort Worth & Denver Railroad, via Texas, to work as the foreman and master painter in the Chicago & Alton paint shop in 1902.

John and his painters did a variety of tasks, from painting the exterior of freight cars and applying stenciled lettering, to creating fine high-gloss, multi-layered finishes on passenger cars and elegant hand-painted or gold-leafed details. As foreman, he assigned and supervised all these tasks.

As the shop’s master painter, John was responsible for the more elaborate and delicate hand-painted details, as well as fancy lettering on passenger cars. This work often included the application of gold leaf.

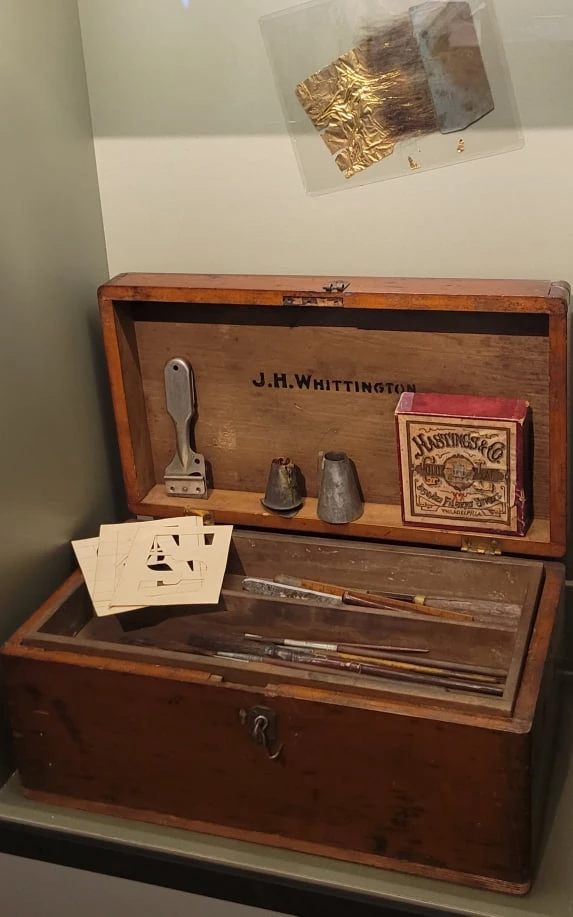

Gold-leafing kit with tools, circa 1900

View this object in Matterport

John used this gold-leafing kit while working for the C&A shops. It included a variety of brushes, stencil-making tools, stencils, and marking tools, in addition to gold leaf. When he retired in 1936, John gave the kit to Bloomington city painter Henry Woizeski who used it until the mid-1950s.

Donated by: Myrna Park

918.980

Joseph D. Penn’s (1898-1987) first job was tool boy for the C&A shops’ superintendent. He was 16 and used his roller skates for speedy delivery of tools.

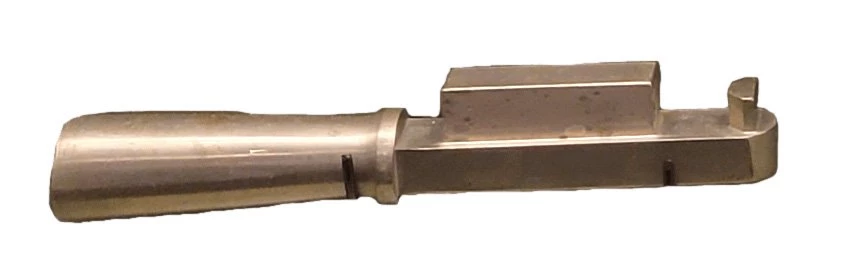

Soon after that he started a machinist apprenticeship to learn how to repair locomotives. Joe used a variety of wrenches, levers, and other tools (often made in the shops) to remove, adjust, or tighten pipes, valves, and other parts of the locomotive. When he completed his training, he was placed on the roundhouse night shift where he made sure engines were prepared for their next trip to Chicago, St. Louis, or Kansas City. When parts broke down, Joe had to make new ones.

“I liked it because you were on your own. If something happened here you had to figure it out...you had responsibility and I loved it.”

— Joe Penn, 1981

In July of 1922, Joe and 1,800 of his fellow shop workers walked off the job along with 400,000 additional railroad workers across the U.S. Their grievance: the railroad had cut their pay and overtime for the second year in a row. The company refused to negotiate with Joe’s union, Machinists Lodge 342. National Guard troops arrived to protect railroad property and replacement workers, and a sweeping court injunction severely limited strike activity.

Four months later a federal injunction forced strikers to return to work at the lower wage rate.

Do you think Joe accepted this and returned to work, or found another job?

Despite circumstances, Joe stayed at the shops. He and his coworkers reorganized Machinist Lodge 342 in 1926 and began to renegotiate their work conditions.

The Alton shops employed 1,200 workers, including Joe, in 1946, when the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio Railroad (GM&O) took over. The GM&O purchased new diesel-electric locomotives, which were easier to maintain and required fewer skilled workers. Joe had 28 years of seniority, but was sent to the Springfield roundhouse until 1950. When he returned to the Bloomington shops, the work force was only 460 — a reduction of more then 60 percent.

Joe retired from the railroad in 1963. But he soon discovered that he did not like being idle and went back to work as a highway laborer.

Lever used as a reverser handle on the control stand of a diesel engine, circa 1955

View this object in Matterport

Donated by: John Hoog

2007.035.08

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County