The Cost of Farming – Outbuildings

Most cribs were constructed of wood and, like the one pictured here, measured about 30 by 35 feet.

With an increasing need for livestock feed storage, some McLean County farmers built much larger cribs. On the Welsh farm south of Gridley, a 30 by 70 foot crib was built. The slatted walls allowed the circulation of air, which helped to dry the corn quickly so it would not mold or rot.

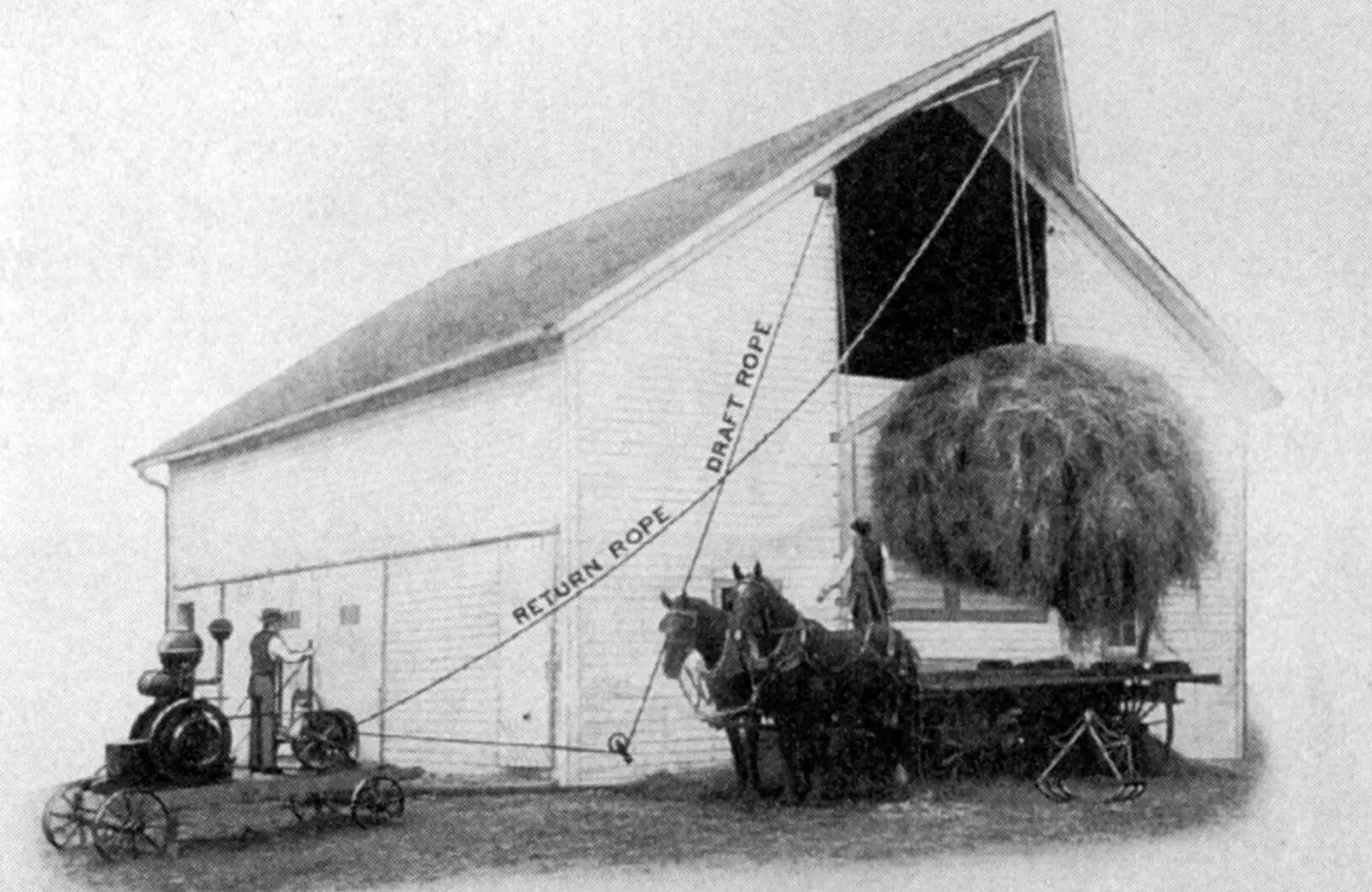

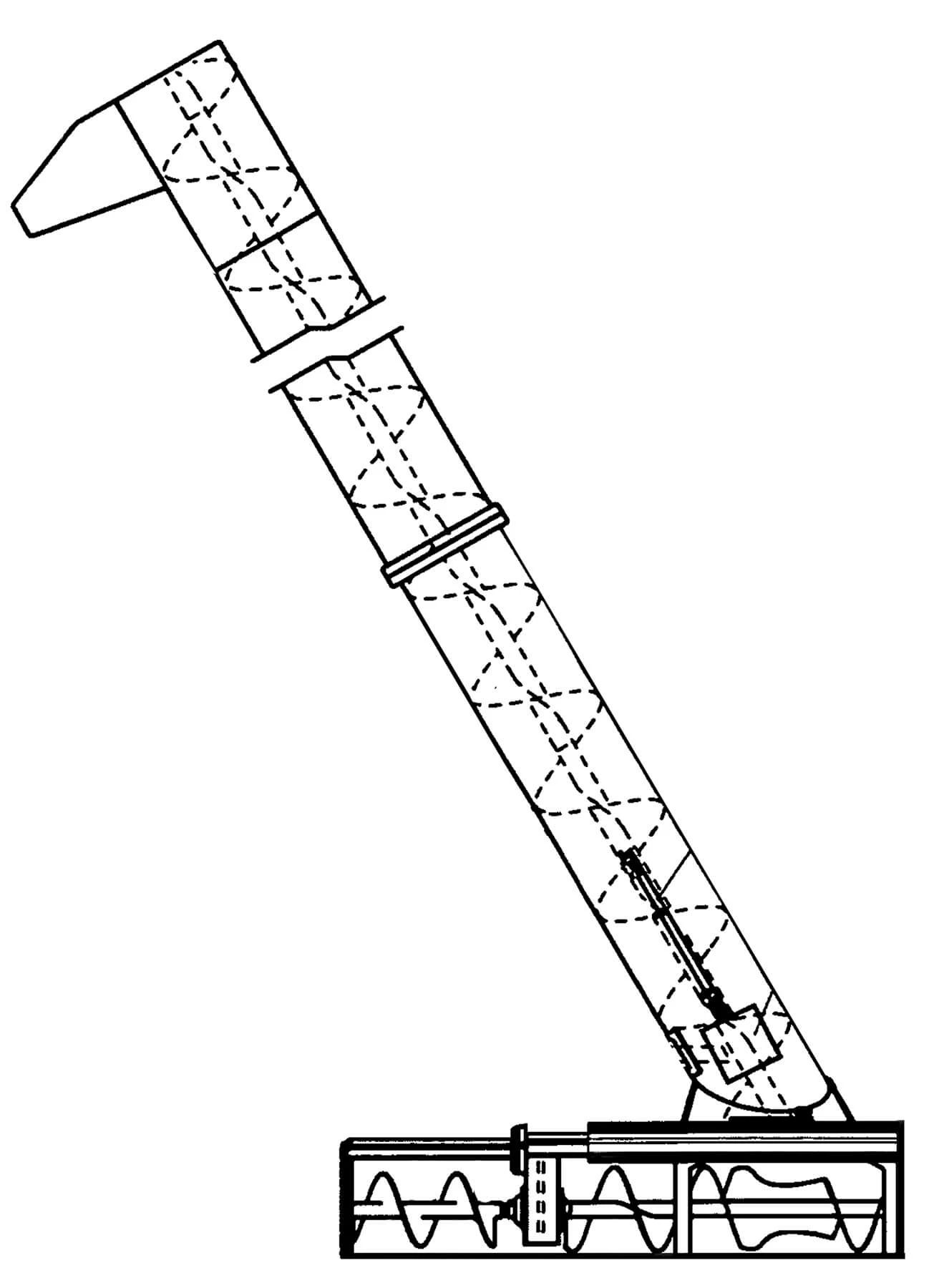

Labor saving portable elevators, first introduced in the 1890s, were used to “elevate” ear corn into storage cribs.

Ear corn was dumped from the farmer’s wagon into a hopper. A belt with scoops passed through the hopper where it picked up the ear corn and moved it up the device to be dropped into the crib. At first powered by horses, area farmers switched to tractor power soon after they purchased a tractor. Such devices were common on McLean County farms.

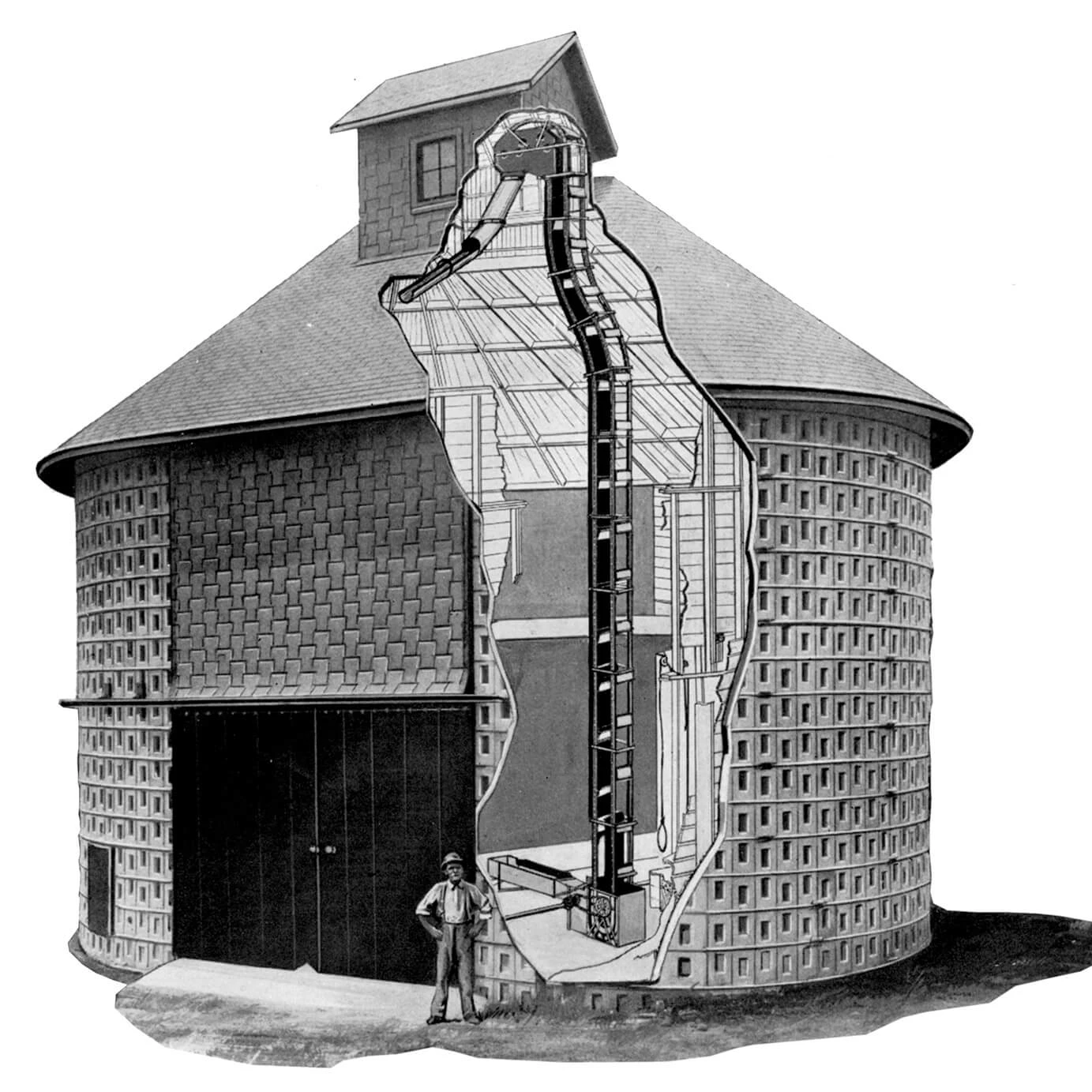

When concrete products began to be manufactured, Bloomington’s Portable Elevator Manufacturing Company patented a concrete block corn crib.

The crib featured one of the company’s patented interior elevators. It moved ear corn to the two ventilated storage areas on either side of the drive, and small grains to the storage area directly above the drive.

George Perrin Davis had one installed on his Buck Creek Farm south of Gridley. The modern crib, with its solid concrete foundation and blocks, was long lasting and minimized a problem most farmers experienced with corn storage — rats. Davis’ tenant, William Printz, and later Lawrence Gilmore, greatly benefited from the addition of this crib to the farm.

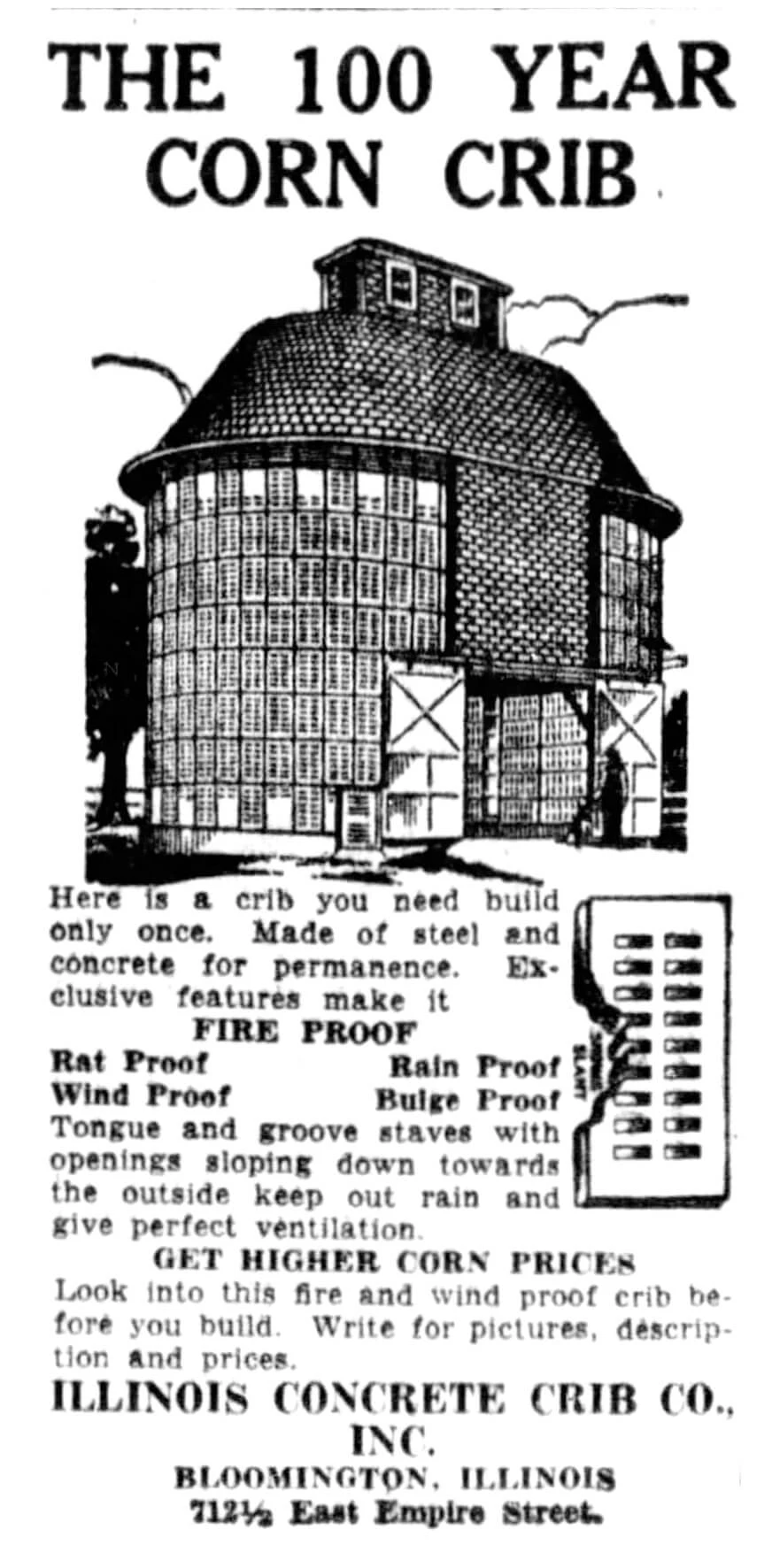

The Davis Ewing Concrete Company also sold concrete corn cribs. Like its concrete fence posts, the company promoted the longevity of its cribs. Ewing sold the company soon after it became involved in a patent infringement case. The Illinois Concrete Crib Company modified its block design and continued to do business into the early 1930s.

Corn and Grain Bins

Corn cribs that stored corn on the ear became obsolete after corn combines, which shelled corn in the field, were introduced. Instead, corn farmers needed grain bins to store their shelled corn.

On-farm storage had a cost, but was typically less than elevator storage. And, if the farmer purchased a dryer, he could harvest his crops sooner, dry them himself, and avoid price deductions at the elevator when he sold them.

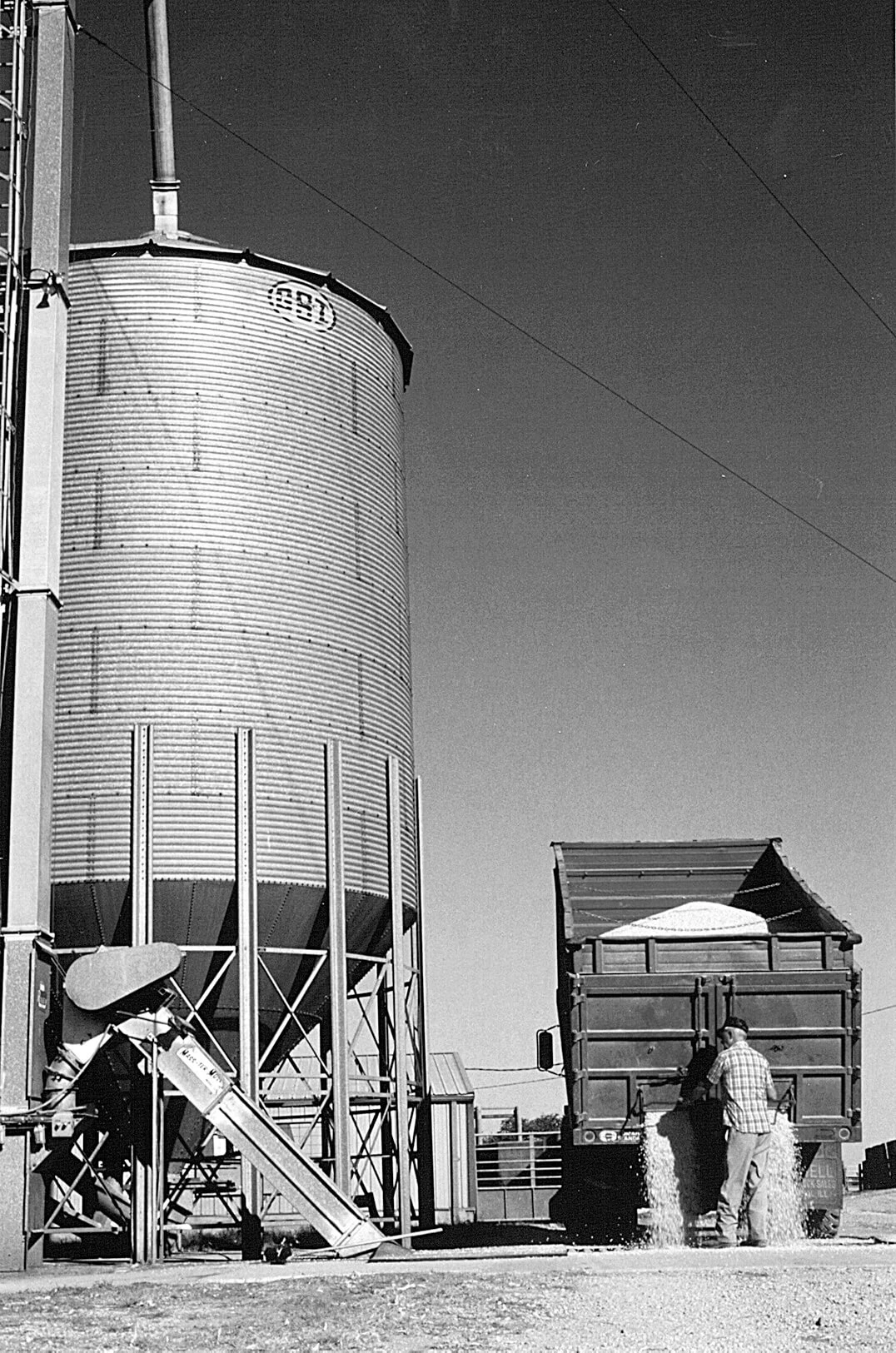

Raymond Park, tenant farmer on the Larry Funk farm near McLean, supervised the installation of this grain storage and drying system in 1959. With the help of his hired hand, the two could combine 20 acres of corn per day and dry 2000 bushels.

With 300 acres of corn, Park hoped to fill all eight grain bins—a total of 30,000 bushels of corn. Funk paid for the new augers, dryer, and storage and the two split the cost of the fuel and oil needed to run the dryer and fans.

As corn yields approached 200 bushels per acre in the last half of the 20th century, on-farm grain drying and storage systems continued to get bigger and more complex.

Why do you think farmers were willing to invest in this equipment?

Many farmers chose to store their grain because they could earn higher profits if they waited.

In 1965 the Bloomington Pantagraph reported that, in the previous 20, years farmers who held on to their grain during harvest and then sold it between mid-November and mid-July earned as much as 17.5 cents more per bushel, depending on the market.

Machine Sheds

By the 1970s converted wooden barns and sheds were no longer big enough to store and protect the equipment McLean County farmers purchased.

Metal clad machine sheds, constructed with square wood posts and sheet steel or aluminum siding, were an economical replacement that also provided space for working on farm machinery.

As equipment continued to get bigger, so did McLean County farmers’ machine sheds.

By the late 1990s some of these sheds featured airplane hanger doors—the McLean County farmer’s best solution for getting large and expensive tractors, combines, and other equipment out of the elements.

In 1996 Dry Grove farmer Joe Hartzold built a 90 x 90 foot shed with a 21 foot ceiling to provided storage for his large equipment as well as space for working on it.

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County