The Cost of Farming – Farm Improvements

Improvements were required on all frontier farms, as the first farmers had nothing but the land when they arrived.

Fortunately for McLean County farmers, the natural resources were abundant.

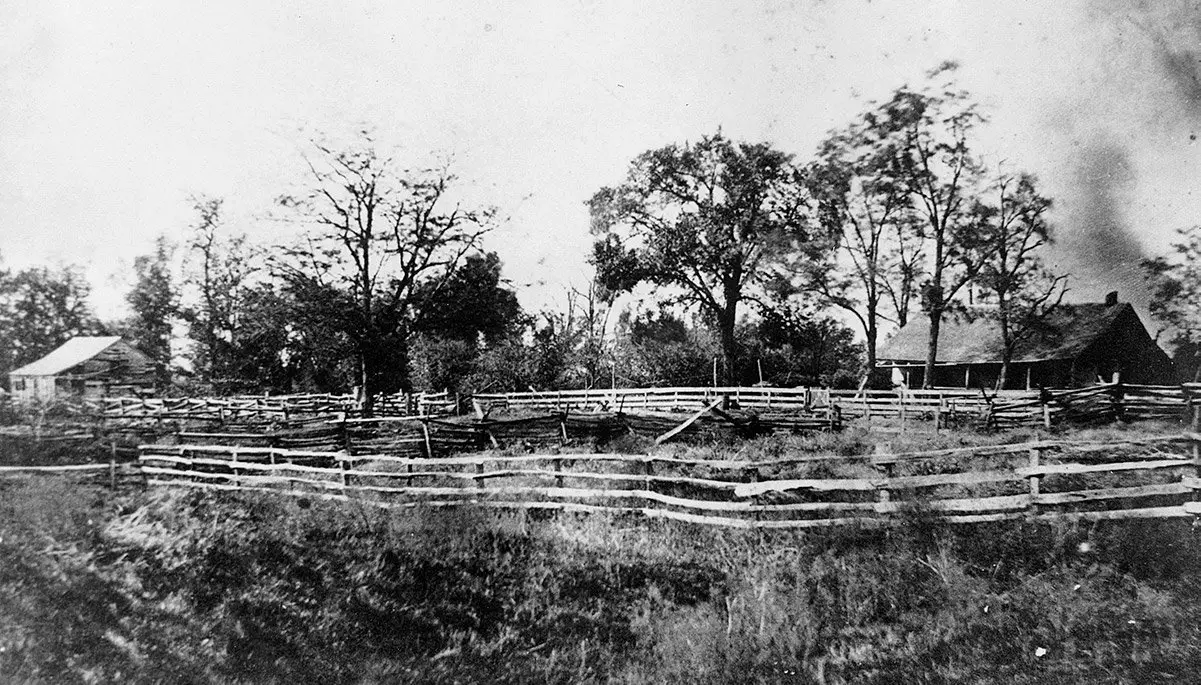

The Thomas Karr family settled in Randolph Township in 1834. With plenty of timber nearby, they built a log home, split rail fencing, and a barn for their animals.

Farmers expanded their farms and increased production. They needed additional space for housing animals, storing crops (hay, wheat, oats, and corn), and for equipment.

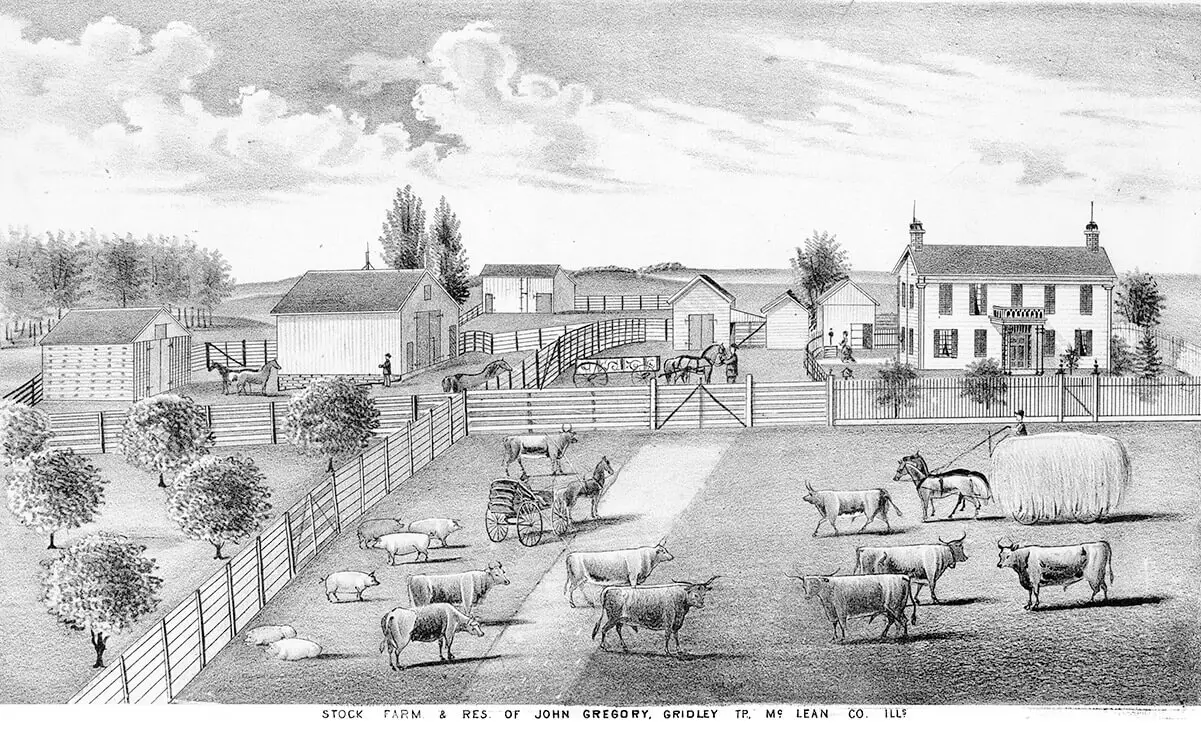

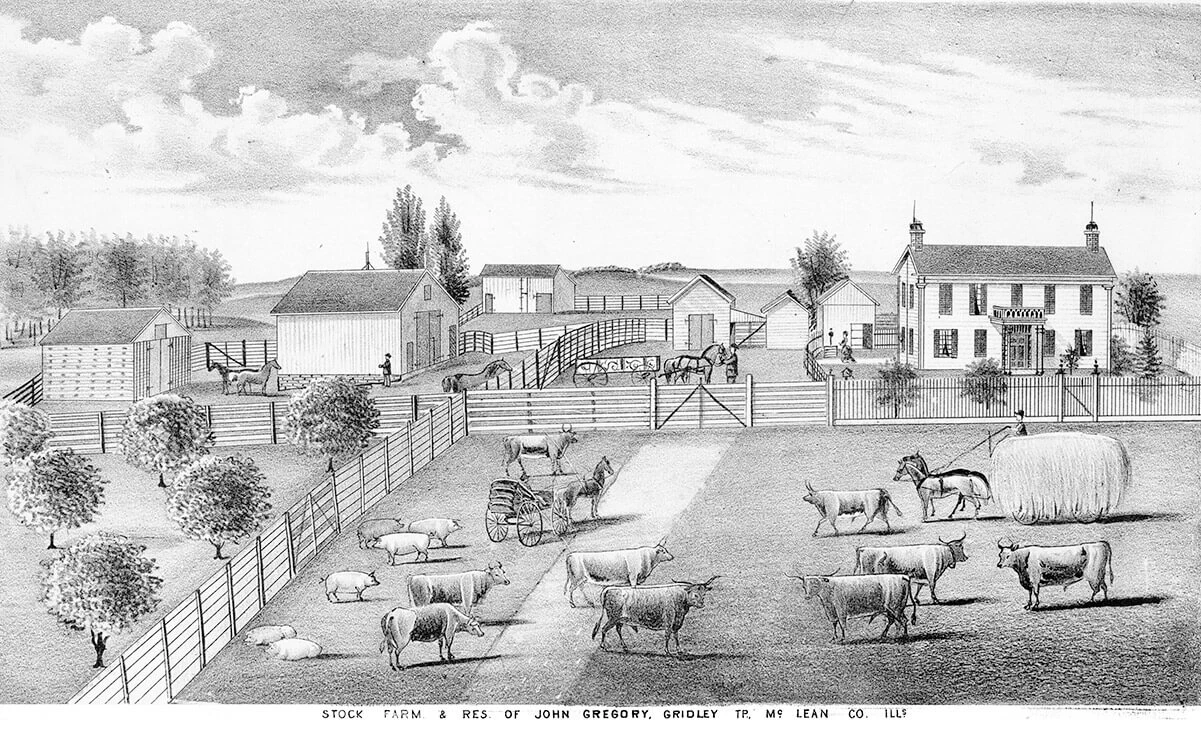

John Gregory purchased 160 acres near Gridley in 1836, and continued to expand the farm and add improvements.

By 1874, when this litho was printed, Gregory’s investment included 2,246 acres of prime McLean County farmland. While he focused on raising livestock, tenants farmed most of the land.

As a good landlord, he continued to invest in improvements, including a barn, sheds, a corn crib, fencing, and a fine home. He also planted an orchard.

Corn cribs, first developed by Native people, were small structures used to dry and store feed corn still on the ear. Their loosely stacked walls allowed for the circulation of air, which helped to dry the corn quickly so it would not mold or rot.

Early cribs, like this one built on the Isaac Funk farm near Shirley, were constructed with poles and rails and sometimes had slanted roofs.

Due to increased income from exports prior to and during WWI, the years between 1910 to 1920 were considered the golden era of farming—a time when area farmers had money to repair and expand existing buildings, and construct new ones.

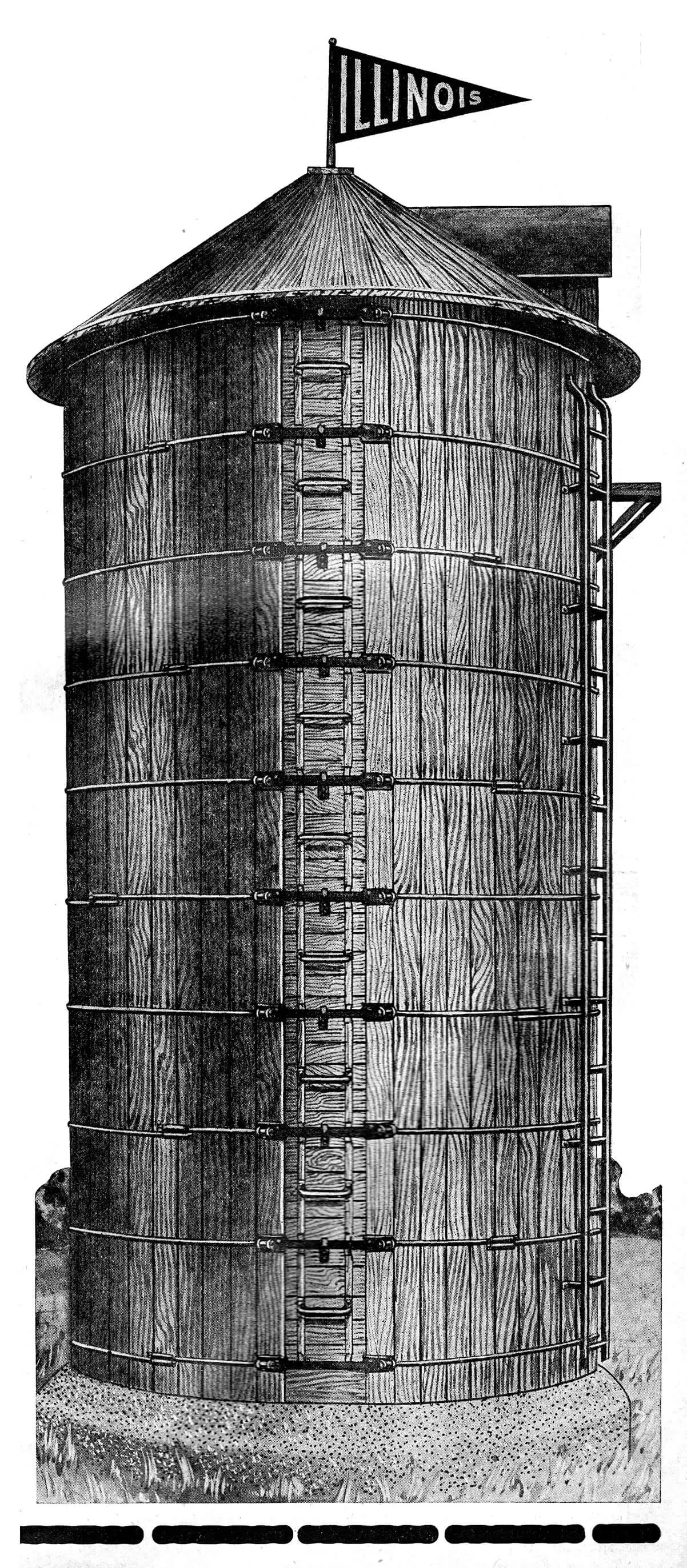

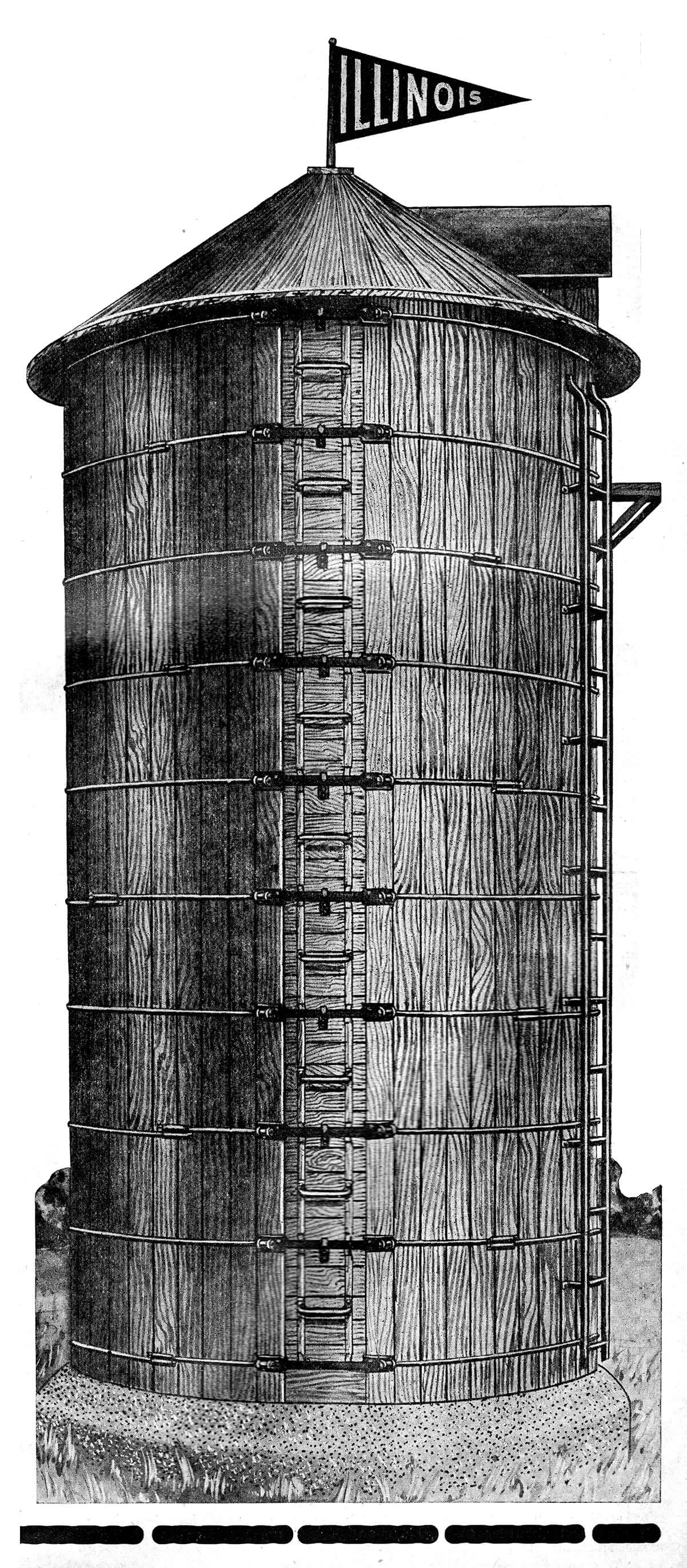

As the number of area dairy farmers increased and silage became an accepted feed, silos began to dot the landscape.

Bloomington’s Illinois Silo Company organized in 1912. The company offered wooden stave silos, like the one in this advertisement, as well as concrete and tile silos.

In January 1913 Bloomington’s Pantagraph reported “between 30 and 40 silos near McLean, and many more to be built that year.”

“The man who has tried the silo knows its value and the man who hasn’t thinks they are alright. . . I have heard only one man condemn the silo, but he does not own or use one.”

— E. Johnstone, Lexington Farmer

Bloomington Pantagraph, September 16, 1913

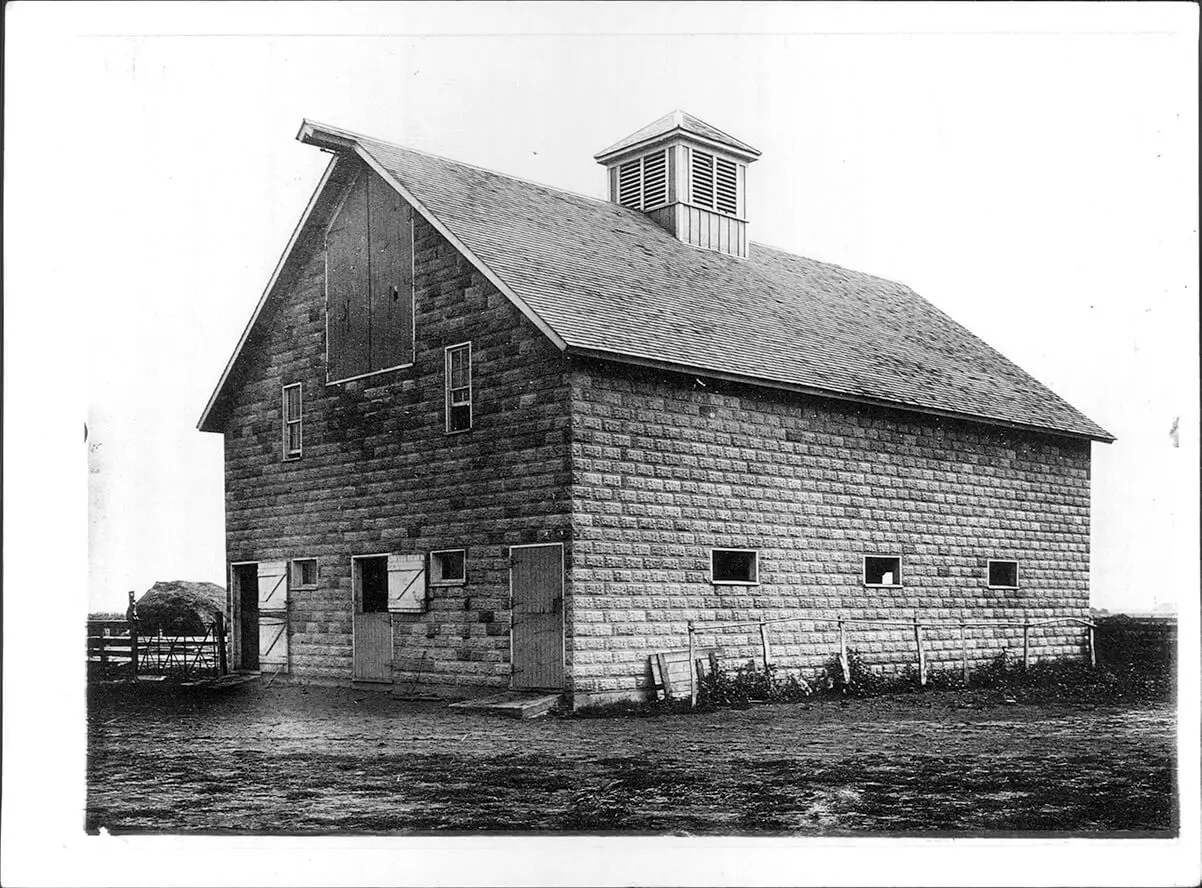

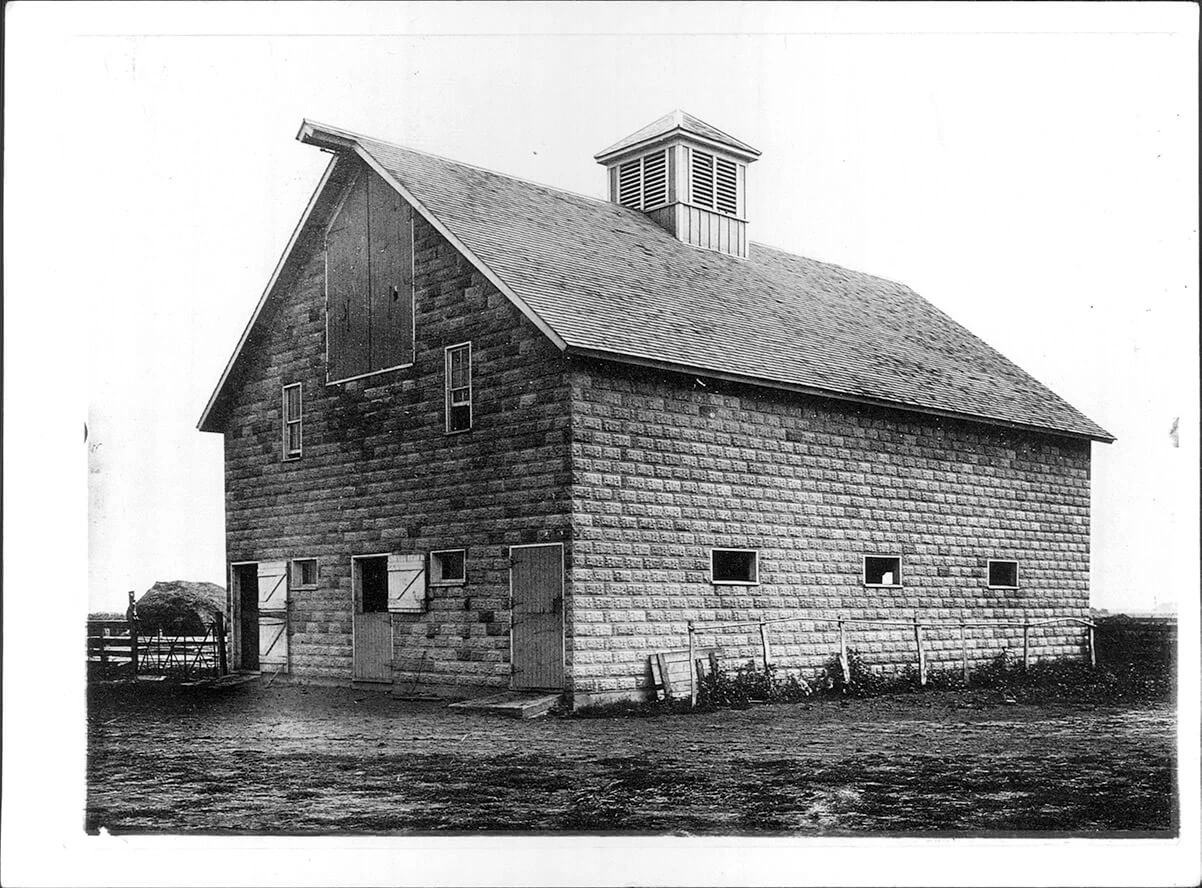

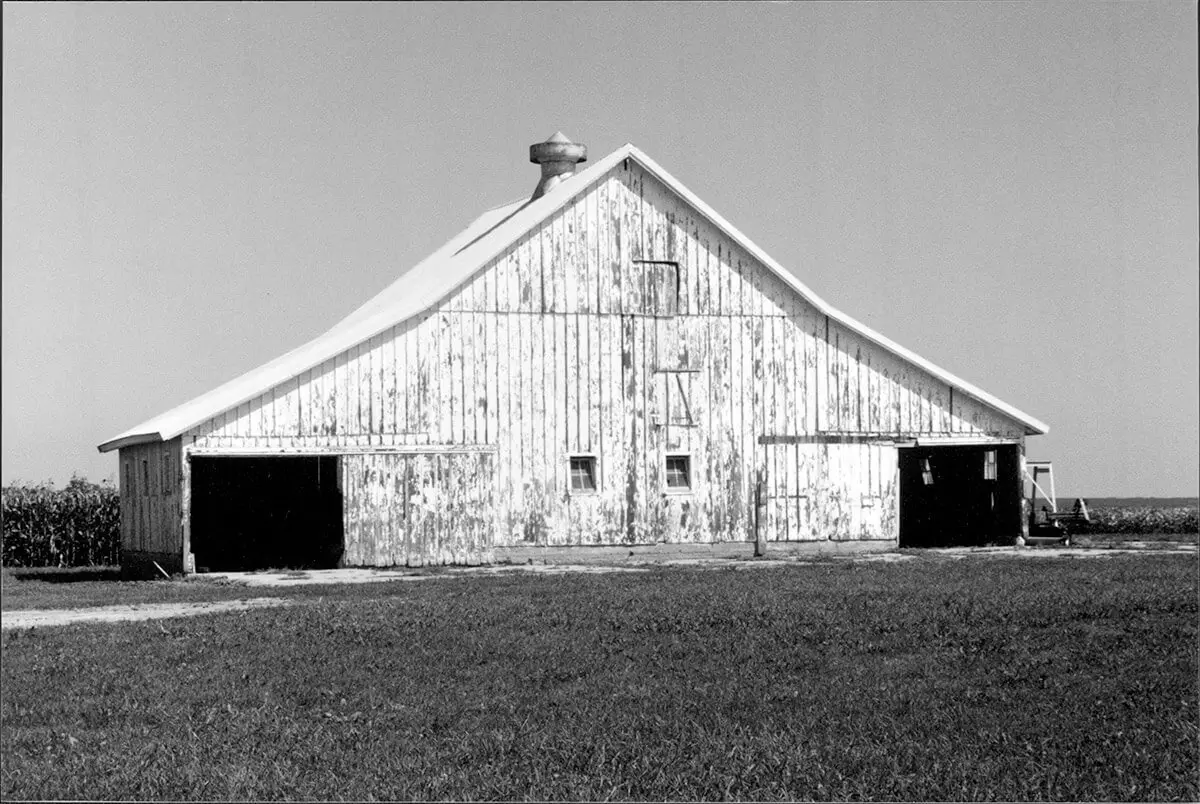

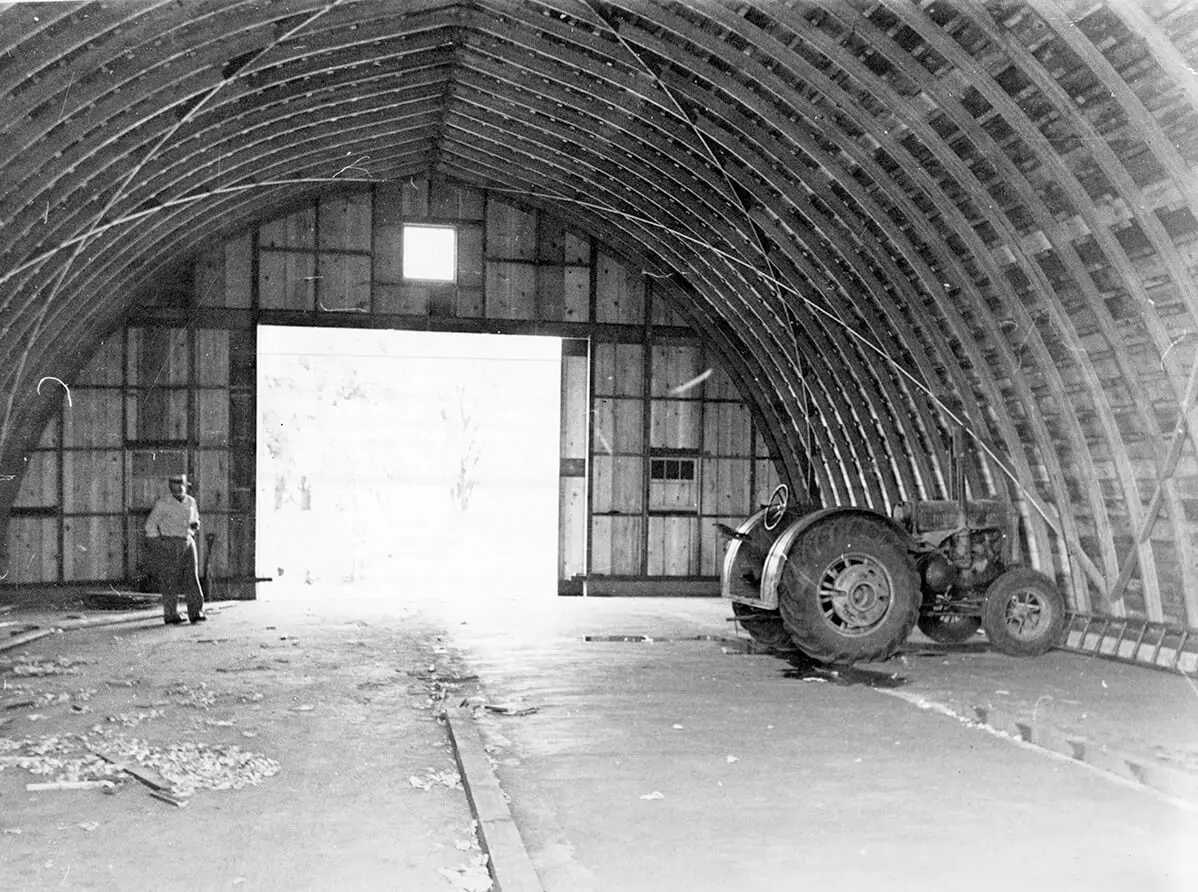

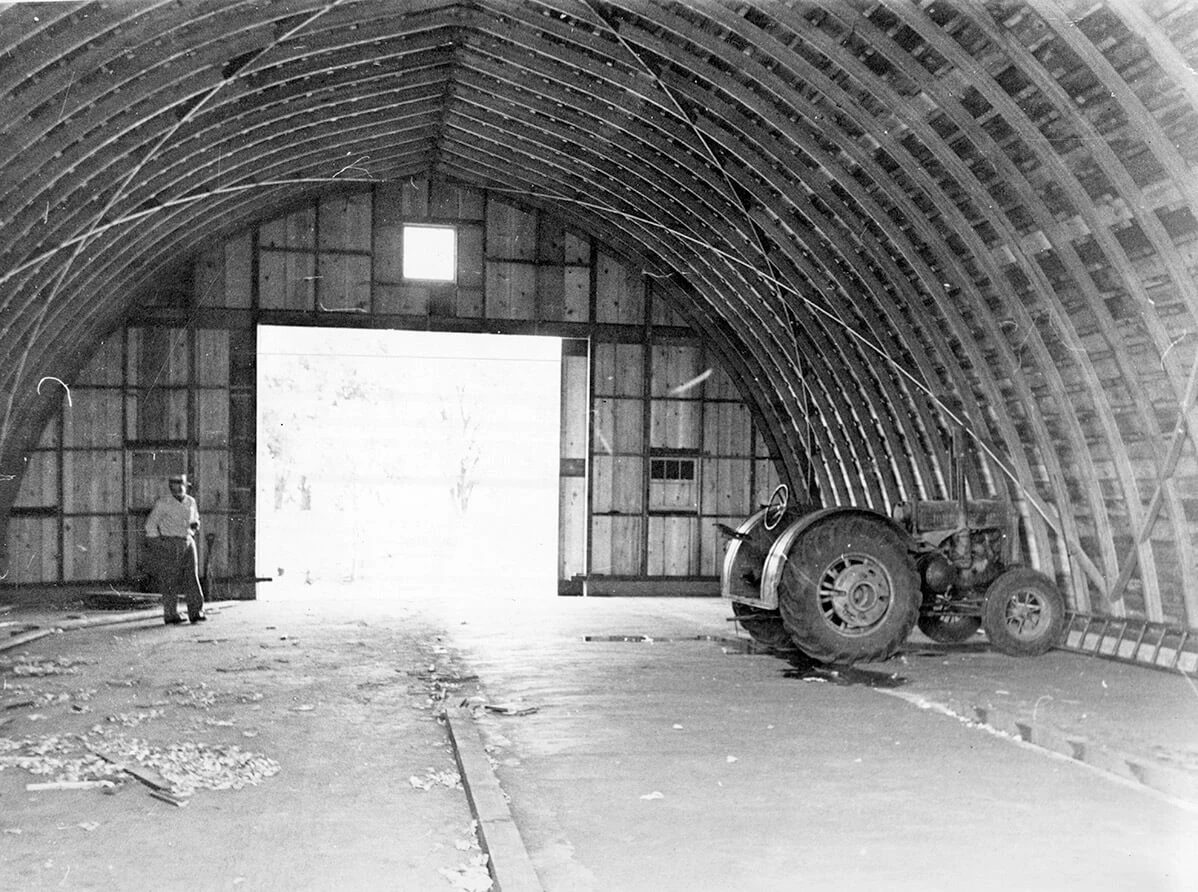

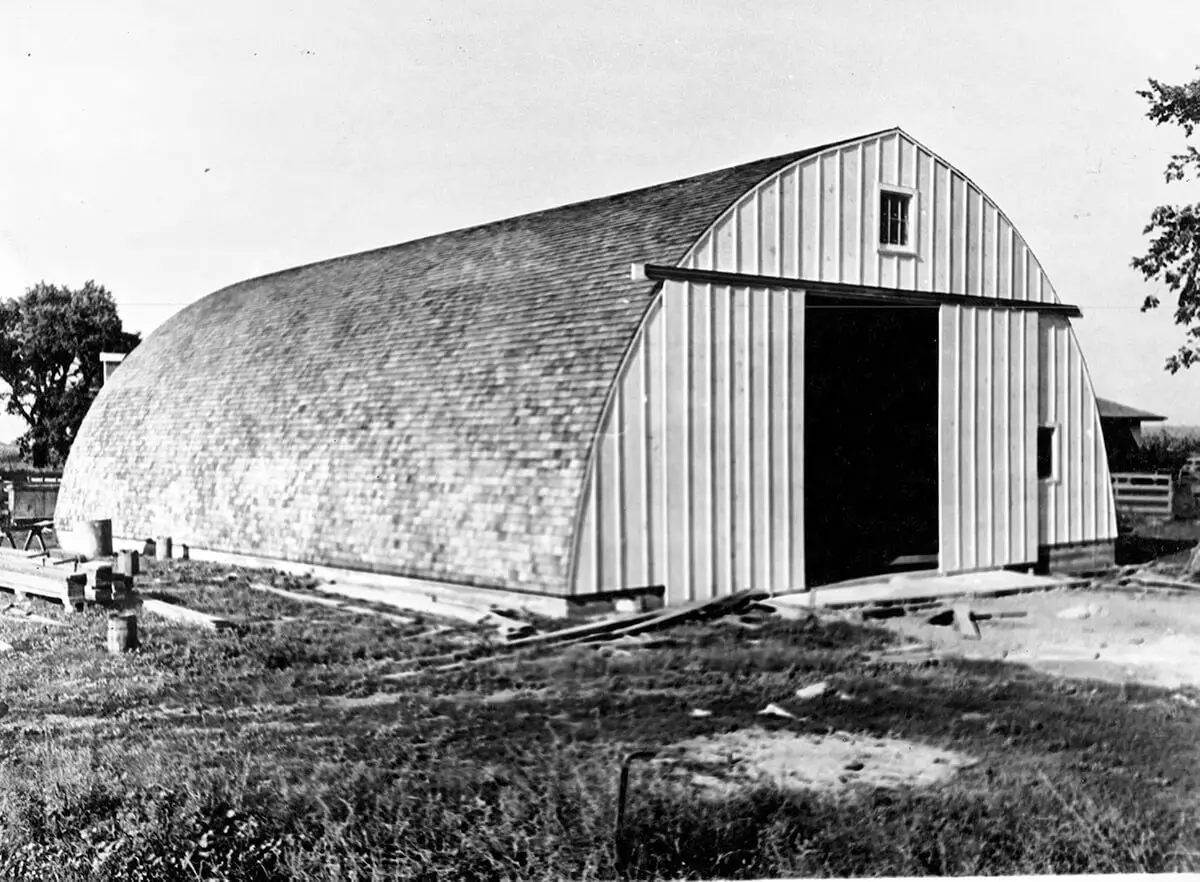

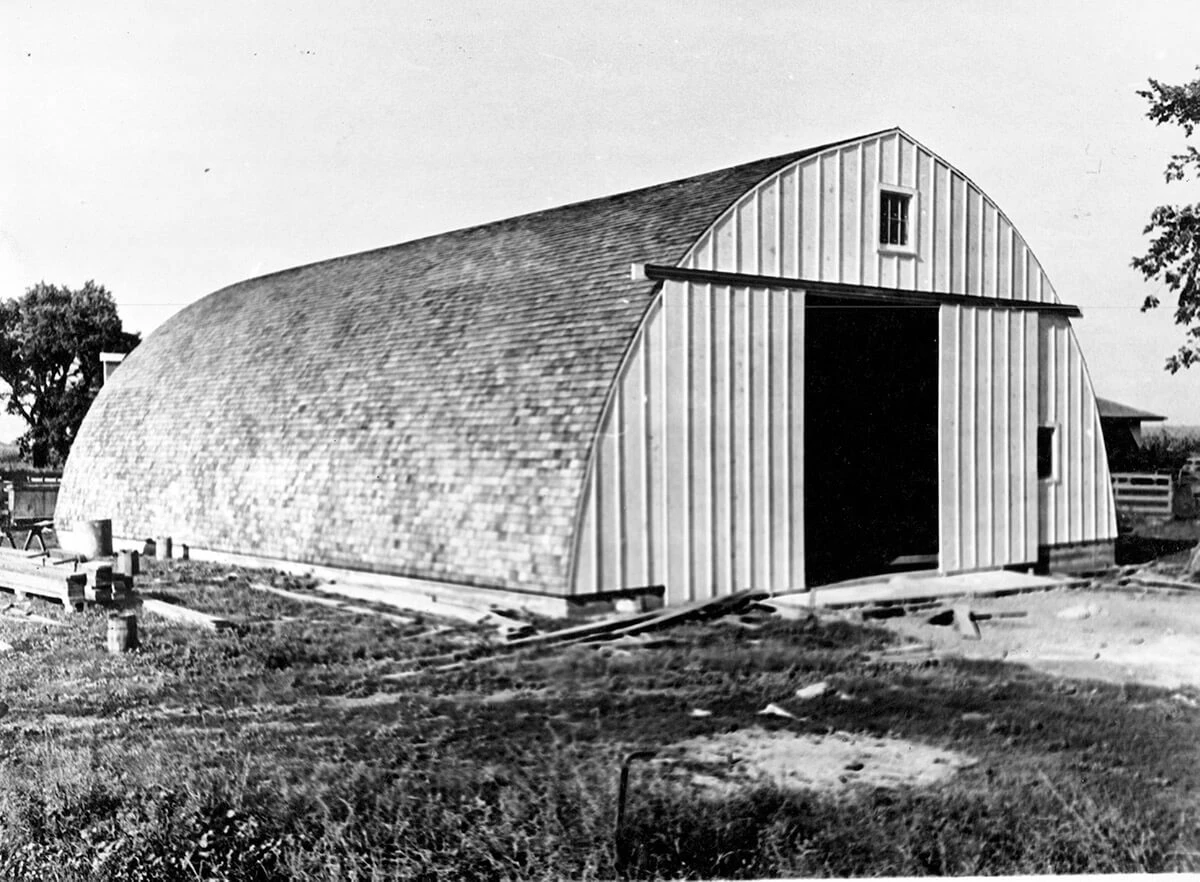

McLean County farmers expanded their older barns and built new ones.

The growing need for equipment and hay storage, as well as for horse housing, necessitated larger barns. The use of concrete for both walls and foundations of farm buildings increased.

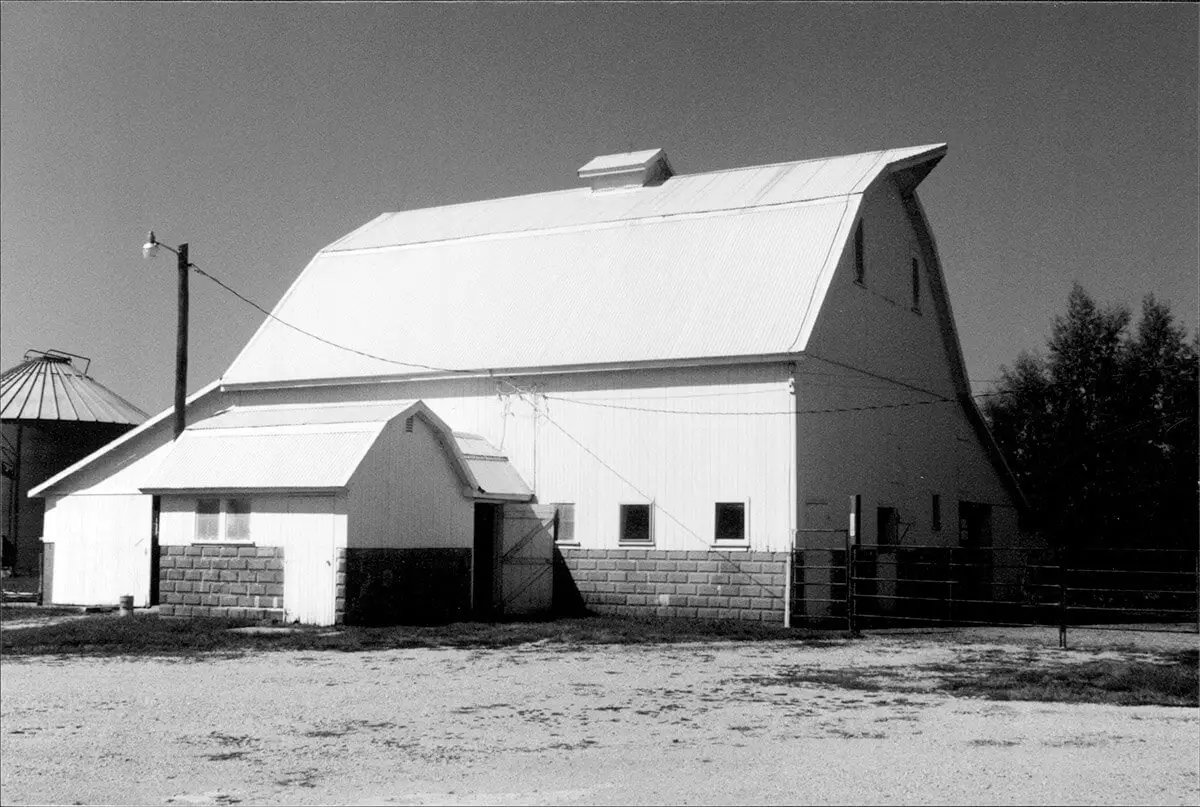

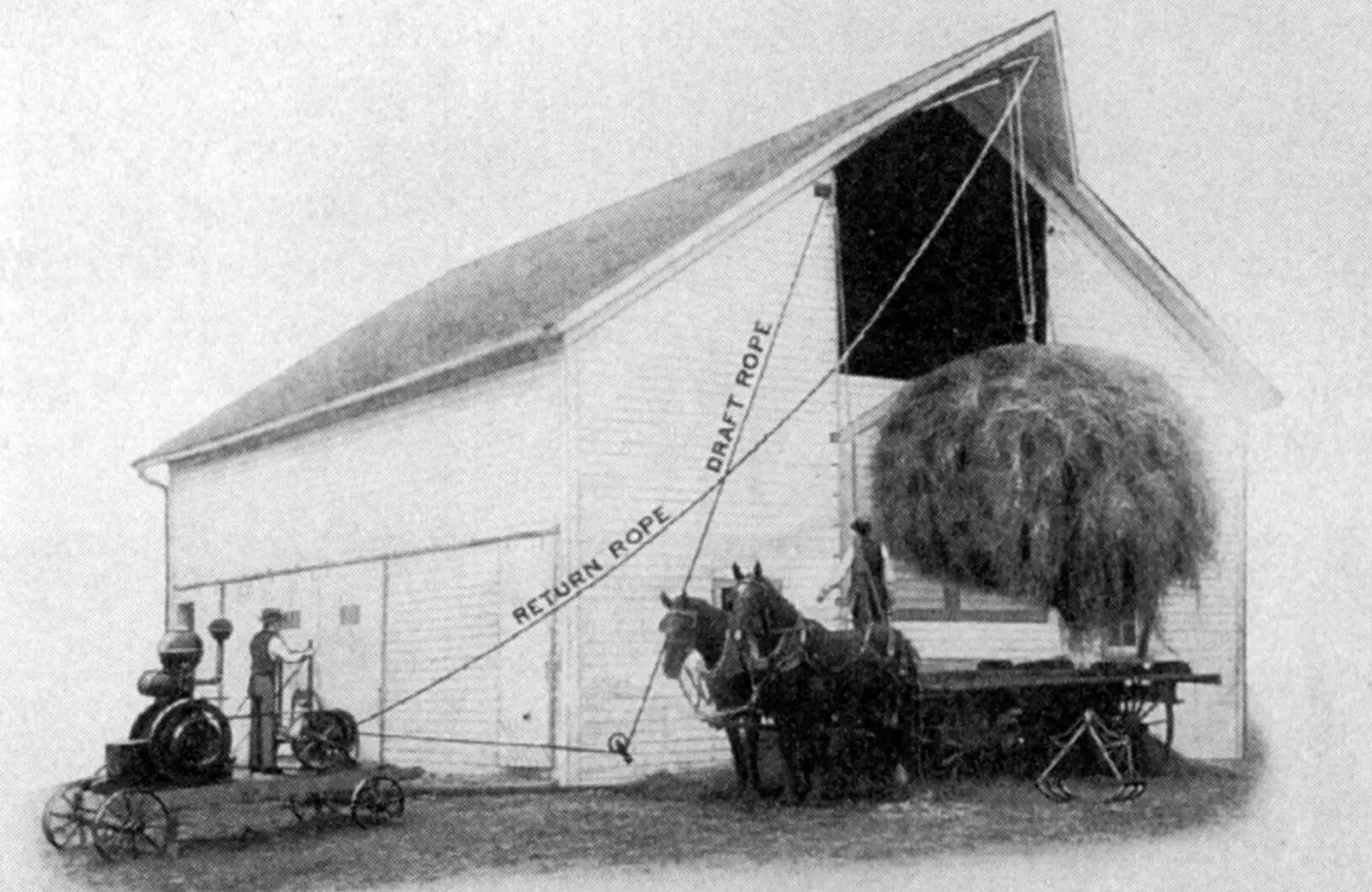

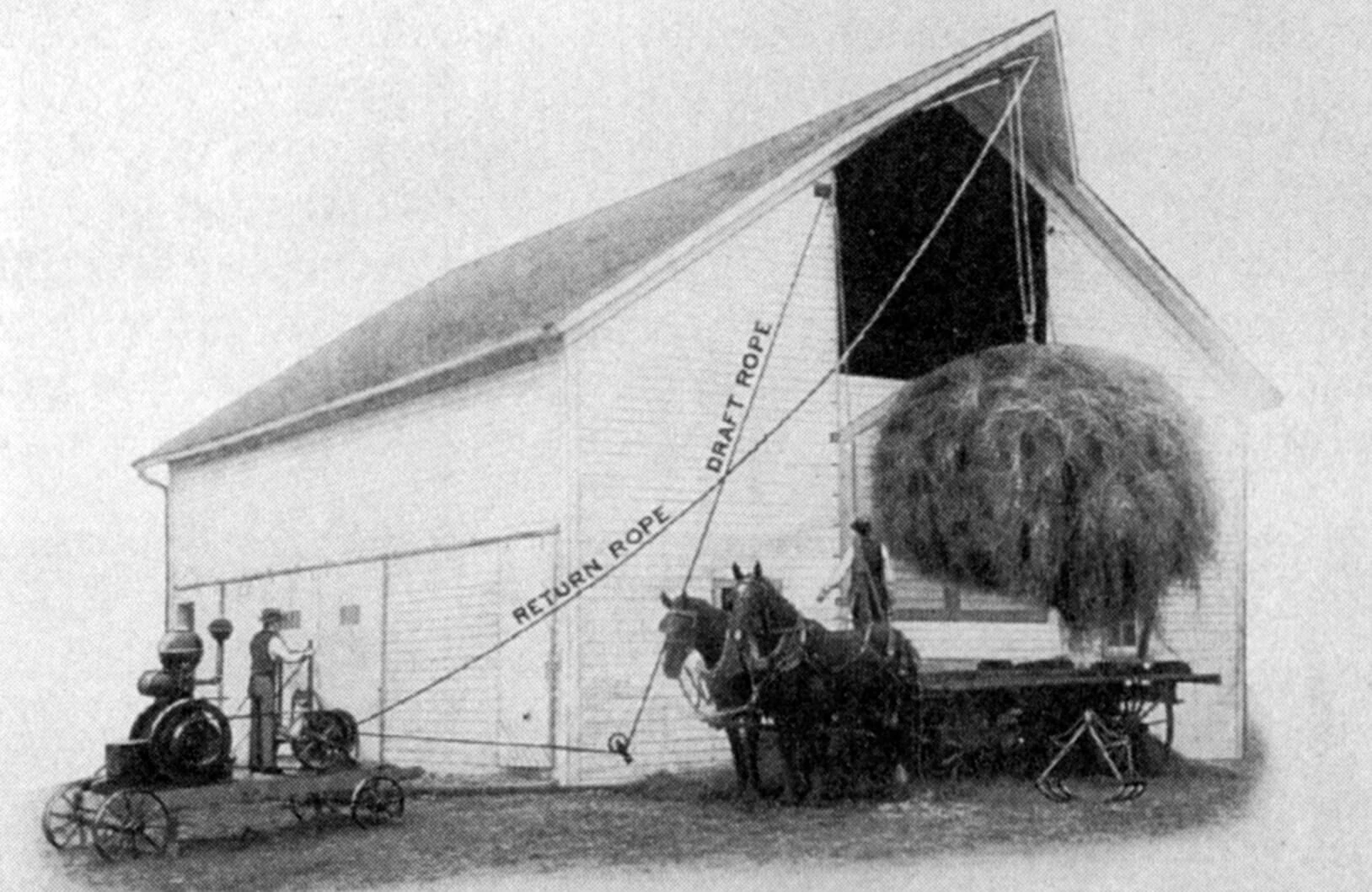

George Perrin Davis built a cement block barn on Buck Creek Farm south of Gridley around 1900. The new barn meant his tenant could “put up” more hay and house more horses. Using the pulley hanging from the extended peak of the roof, hay was raised and then pulled into the barn’s loft.

Barns with gambrel roofs, like this one, were especially popular on dairy barns, as they provided more space for hay than the traditional sloped roof.

Most barns of this style had cement block half-walls. They proved durable against the water and mud the wall was exposed to.

This dairy barn had a milk house conveniently located next to it. Milk from the cows was cooled and stored in this building until it was picked up by the agent who transported it to the local milk processor.

After WWII a new era of building began.

As grain production increased, larger storage facilities were needed on the farm.

In the 1950s and 60s more farmers built storage cribs on the farm, especially if they had livestock that they fed corn.

The choice to build new cribs, intended to last 100 years, was one made without the knowledge of technology to come. In 1954 W.P. Scott, a farm manager with the Peoples Bank of Bloomington, discouraged such construction.

In 1948 William Blagg built a modern corn crib on his 80 acre farm west of Cooksville.

Blagg had used a pole and board crib for 28 years, but figured that for $3,500 even his small farm could afford this modern convenience. Built to last 100 years, the crib was equipped with an inside dump, a grain elevator, and a concrete foundation. Blagg filled his new crib with 3,300 bushels of corn picked from just 341/2 acres of corn – the equivalent of 95 bushels per acre.

“I do not recommend construction of permanent cribs for ear corn. I expect a rapid change to storage of shelled corn.”

— W.P. Scott

1954

Some livestock growers replaced their barns and sheds with specialized buildings.

In 1963 Gridley farmer George Stoller and his son Don built a state of the art facility for raising feeder cattle. The 280’ long shed had four penned areas for four ages of steers, and included slotted floors for easy removal of manure. Food and water was brought directly to the livestock.

“The new Stoller set up is designed to bring in the young calves and never move them until they are fully fattened and ready for Market.”

— Bloomington Pantagraph

1963

As corn yields increased and combines that shelled corn in the field were developed, McLean County farmers began to install on-farm corn bins and grain dryers.

By the early 1970s McLean area farmer Bill Beeler had converted his silo to corn storage and added one grain storage bin and a grain dryer.

In subsequent years Beeler added additional grain storage until he had the capacity to store a total of 155,000 bushels of corn on his home farm and 175,000 bushels total.

Grain storage bins made corn cribs obsolete. Some farmers converted them into machine storage, others let them sit. By the late 1990s, most corn cribs had disappeared from the landscape.

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County