Working in a Dangerous and Challenging Environment

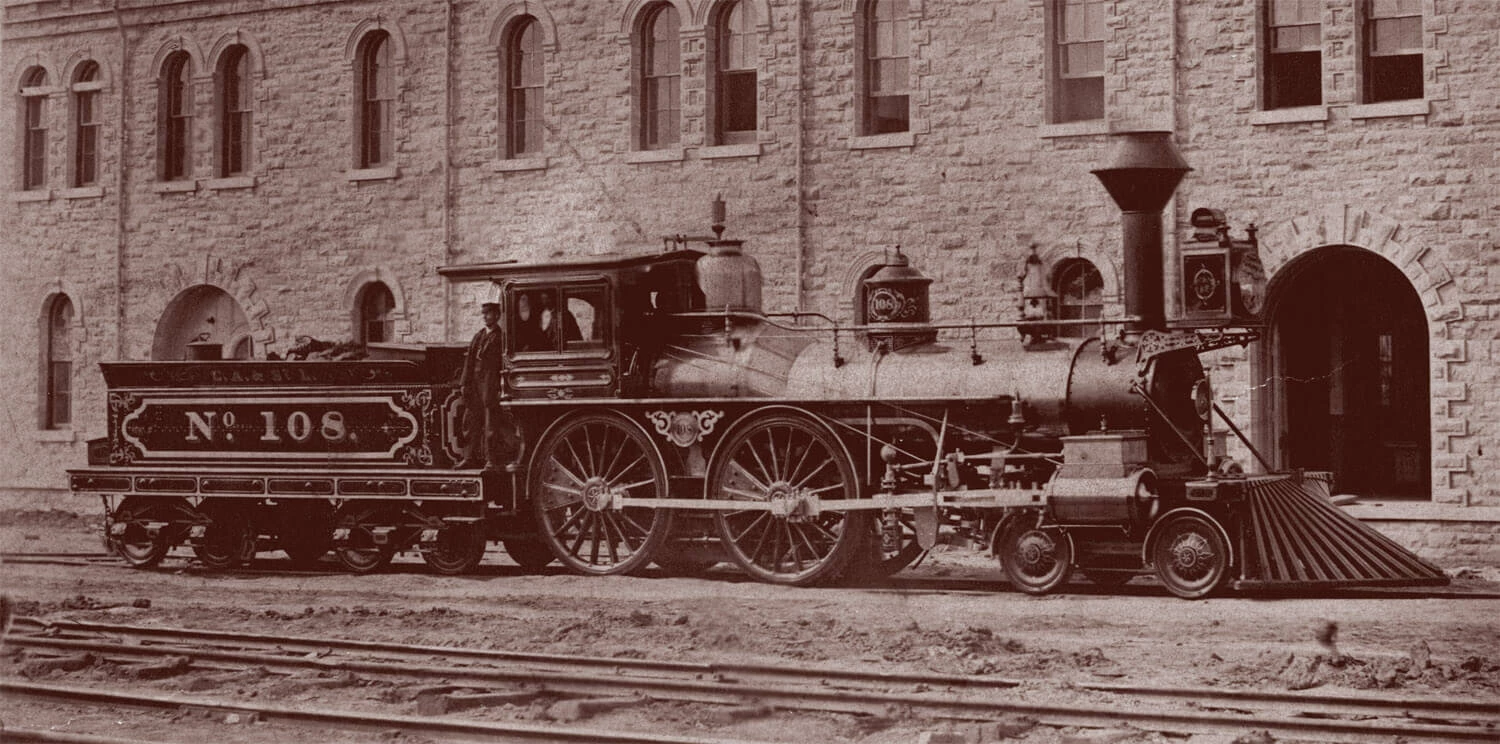

Seth Copp (1823-1890) came west from his home in New Hampshire in 1856. An experienced train engineer, he soon started at the Chicago & Alton Railroad (C&A RR), running the route between Bloomington and Chicago for many years.

Seth was one of just a few engineers given the responsibility of managing a locomotive for the C&A RR. This involved checking its condition and preparing it for service before each run, as well as completing necessary paperwork. During a run Seth operated the locomotive’s throttle to control the speed and the brakes to stop the train.

Seth was also required to know the physical characteristics of the rail he traveled, including passenger stations, the incline and decline of the right-of-way, and speed limits. As the train moved, he watched for obstructions on the rails ahead. Together with the conductor, he also monitored the time to ensure the train did not fall behind schedule, or leave stations early.

The role of railroad engineer was often glamorized. But in fact, the job was demanding and extremely dangerous.

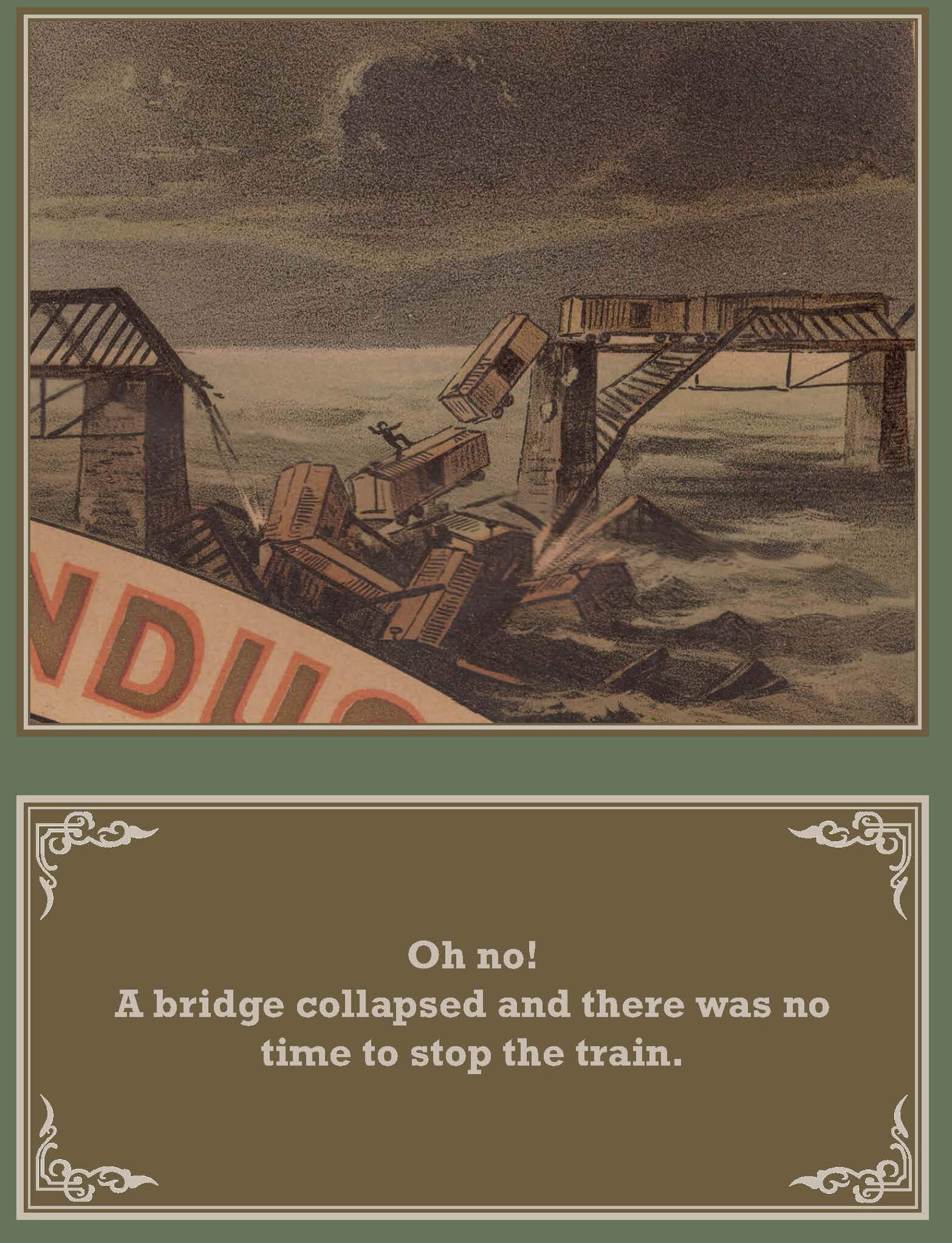

Even the best engineers were involved in accidents, some caused by their own carelessness, some caused by others, or by mechanical failure.

Seth was an exemplary engineer.

Do you think he was ever involved in an accident?

For several years Seth ran a day passenger train between Bloomington and Roodhouse (a small town south of Jacksonville, Illinois). It was on this route near Jacksonville in 1873 that a horse, buggy, and its occupants were hit by the train Seth was running. There was plenty of time for the buggy to cross, but the horse froze on the tracks in terror, as did the elderly women in the buggy. The third occupant, a young boy, was helpless. All efforts were made by Seth and his brakemen to stop the train, but it was too late. The young boy survived, but the two women died soon after.

Despite this accident Seth was...

“a man greatly esteemed by the railway’s officials.”

— Bloomington Pantagraph, February 4, 1890

Seth retired in the fall of 1889 due to ill health.

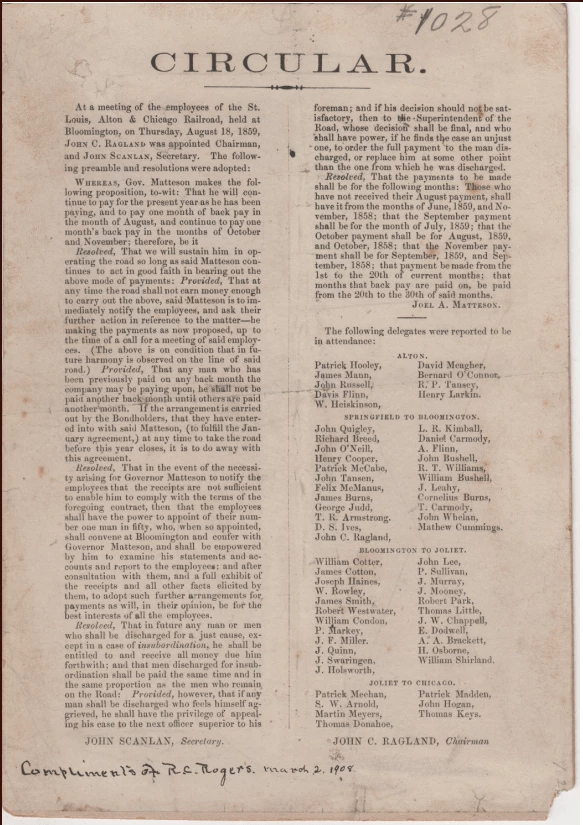

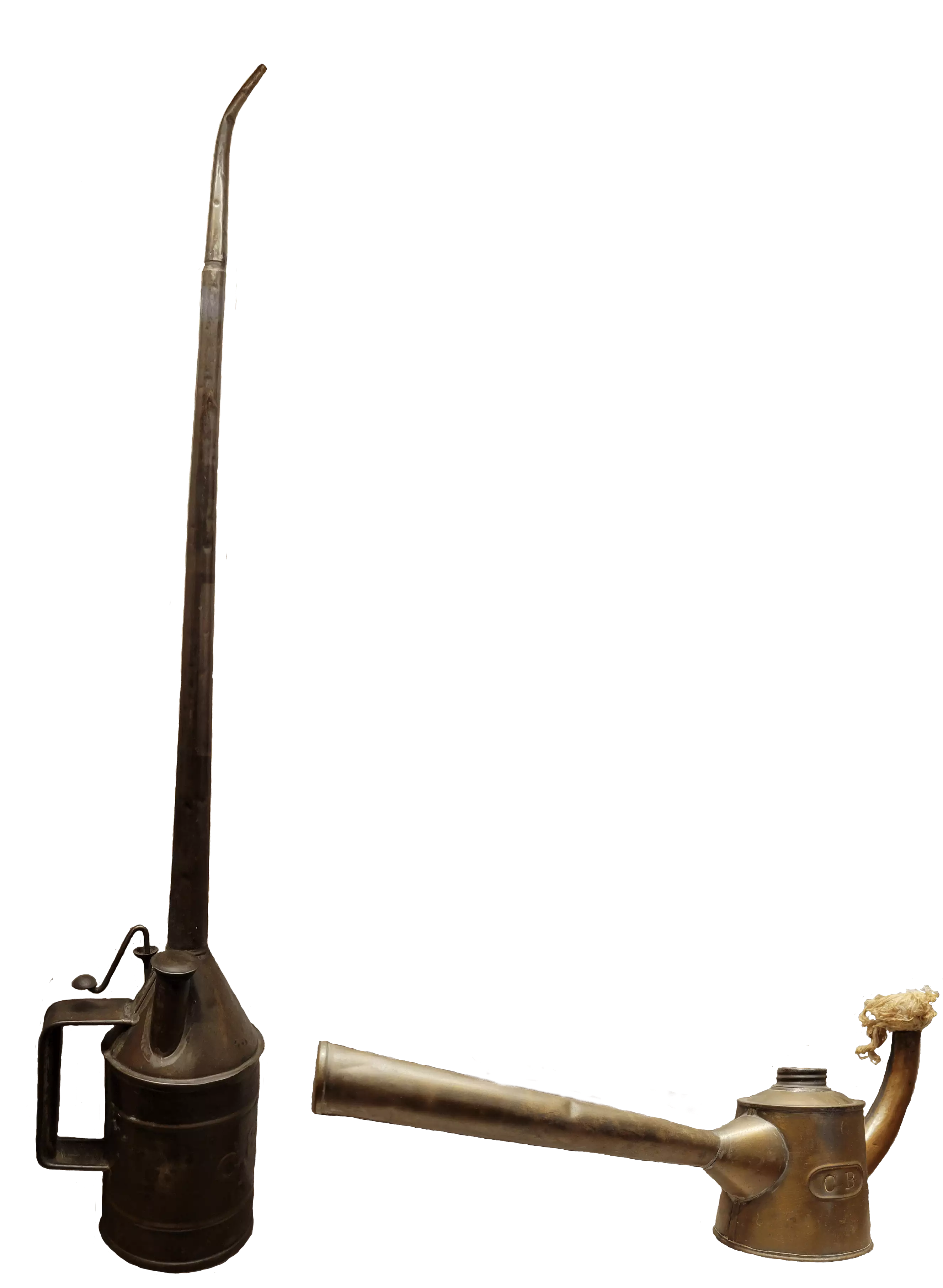

Railroad lamp and oil can, circa 1910

View this object in Matterport

Seth used a number of tools to inspect and service his engine. This railroad lamp and oil can, though dated circa 1910, are very similar to the tools he would have used. Made at the C&A RR shops, they were used by C. H. Broughton who was an engineer for the C&A RR in the early 1900s.

Donated by: C. H. Broughton

728.68, 728.67

Patrick H. Morrissey (1862-1916) was the son of Irish immigrants living on Bloomington’s west side. When he was a teenager, he began his railroad career as a “call boy.” Since there were no home telephones in the 1870s, his job was to run through the west side neighborhoods looking for train crew members and letting them know a train was waiting.

Patrick completed high school in 1877 — one of just five males to graduate from Bloomington High School that year. In 1880 he worked as a clerk for the shop’s master mechanic, then began to work as a freight brakeman.

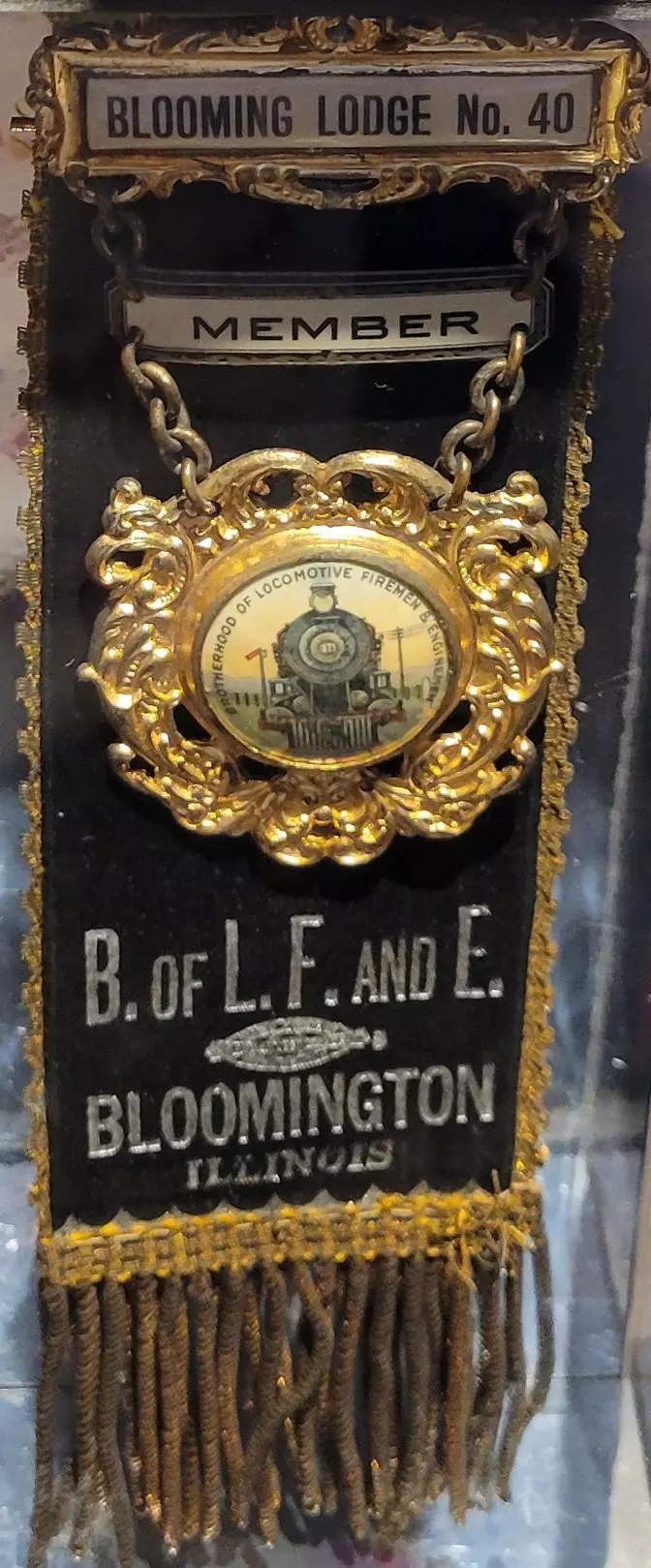

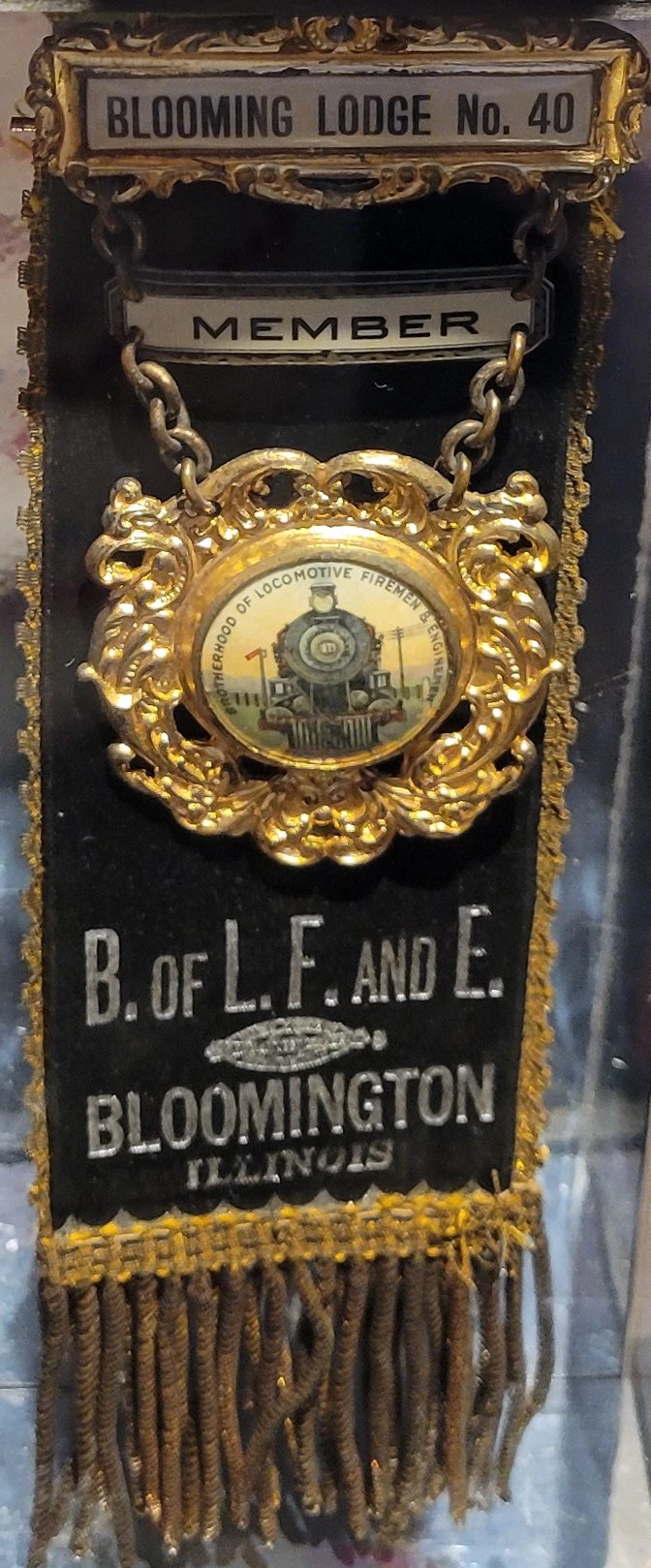

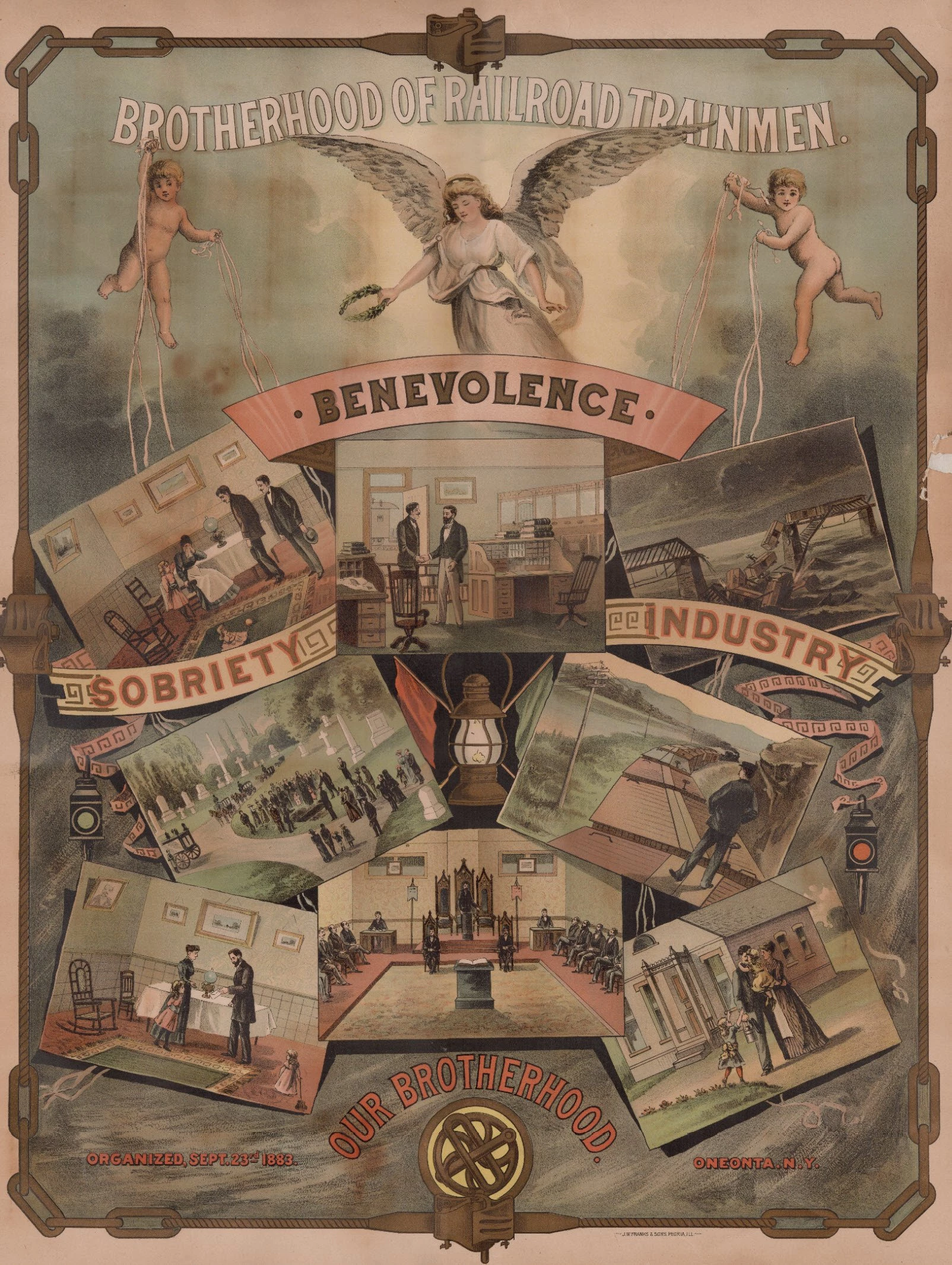

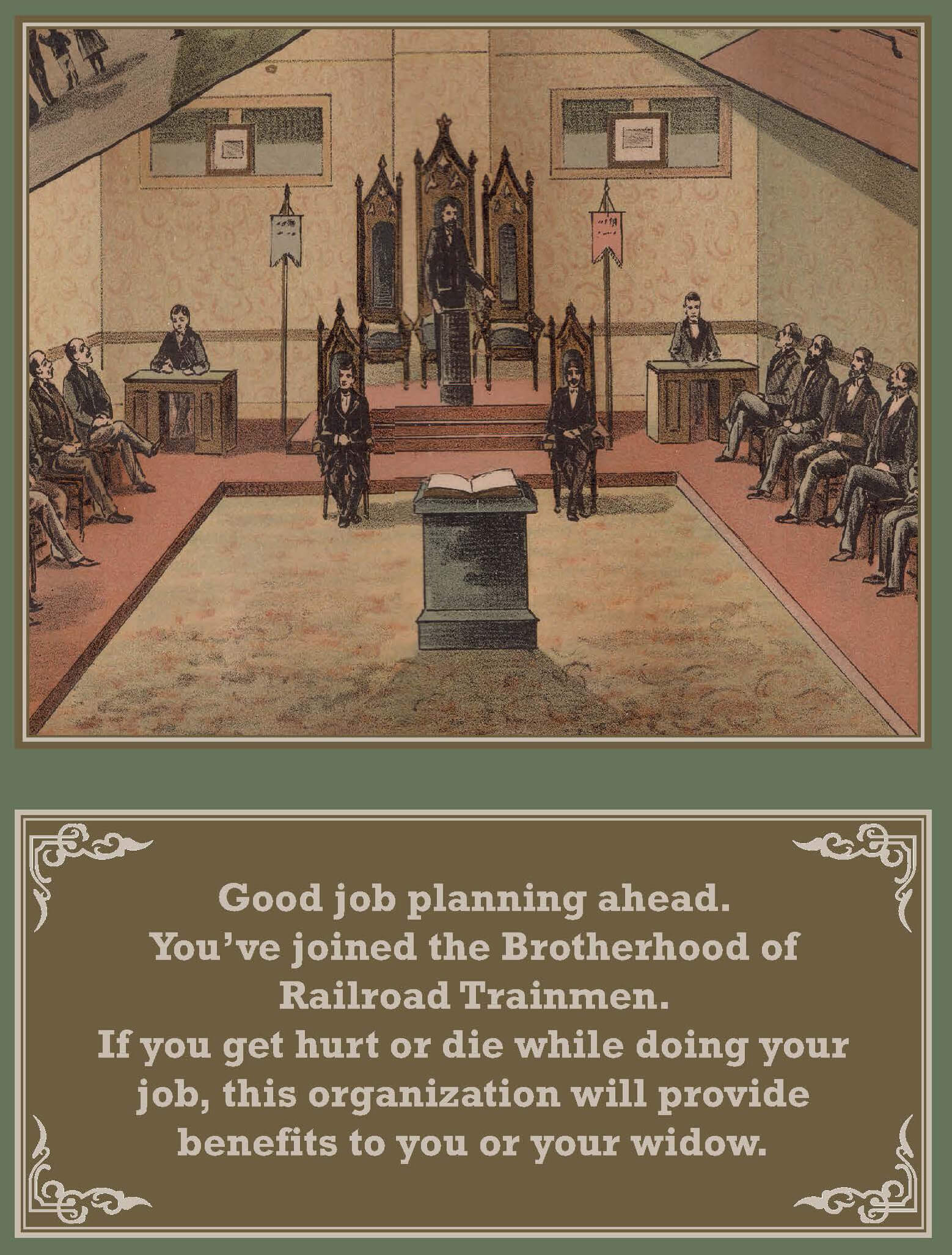

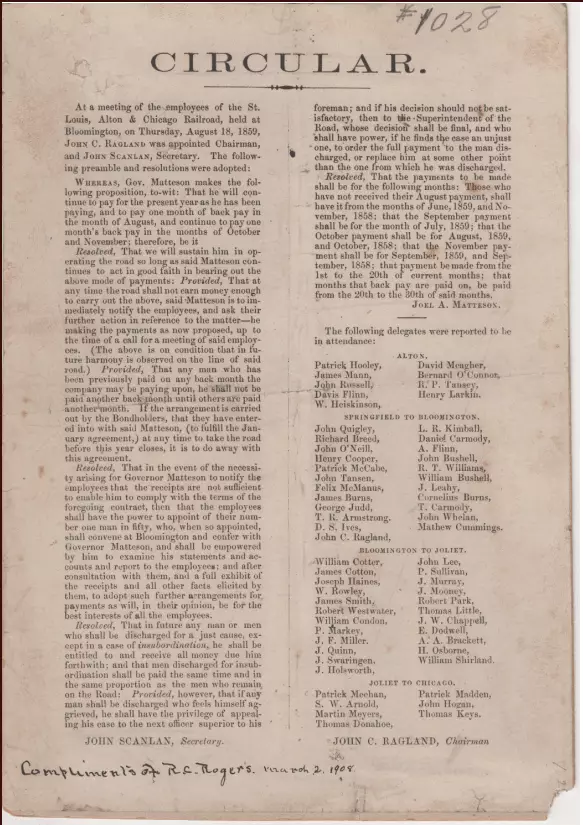

Patrick and other C&A RR brakemen organized a local Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen (BRT) union in 1885.

Members of the Brotherhood agreed to contribute funds if a fellow Brotherhood member was killed or injured. With accident and death rates high, workers joined hoping to provide security for their families if something were to happen to them on the job.

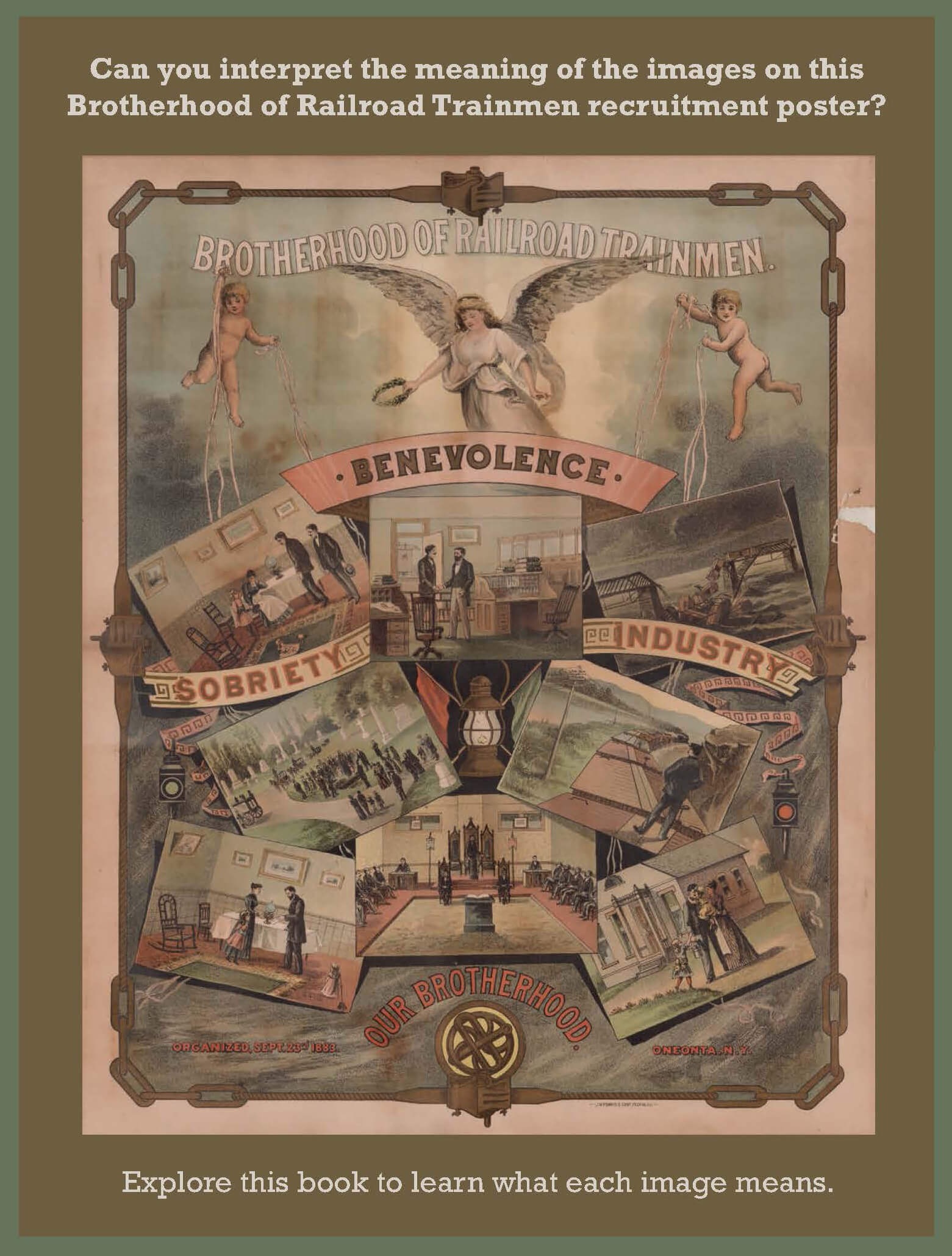

BRT Flip Book

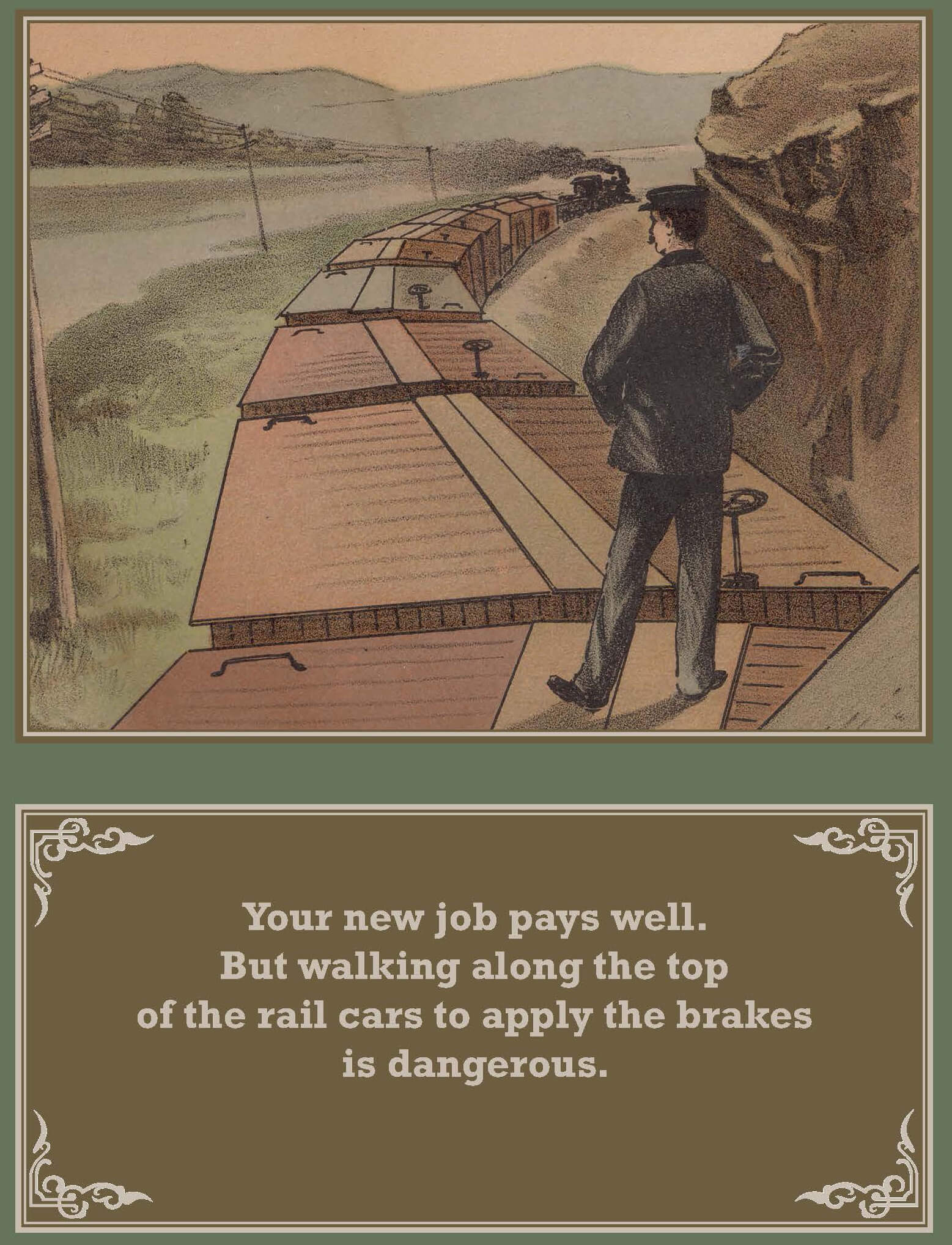

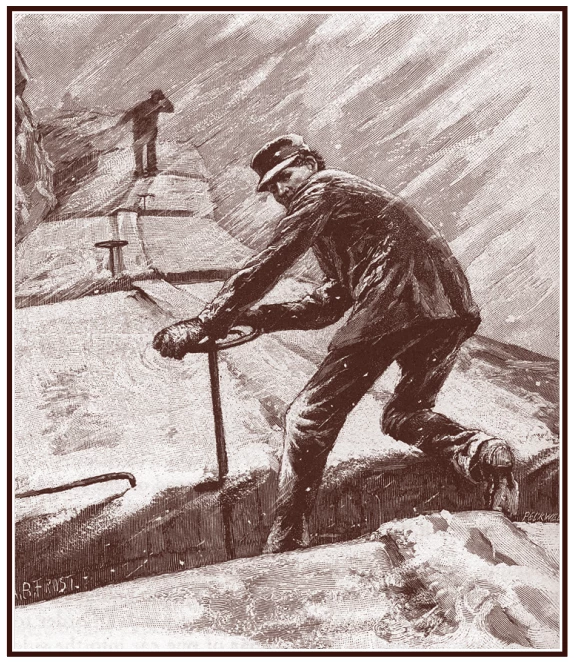

Franklin Ridge (1859–1892) became a brakeman for the C&A RR in 1884. His job was one of the most dangerous.

When signaled by the conductor to brake, Frank ran along the tops of the moving cars and turned the brake wheels for each car in order to stop the train. He had to have good balance and determination as he did this in all types of weather.

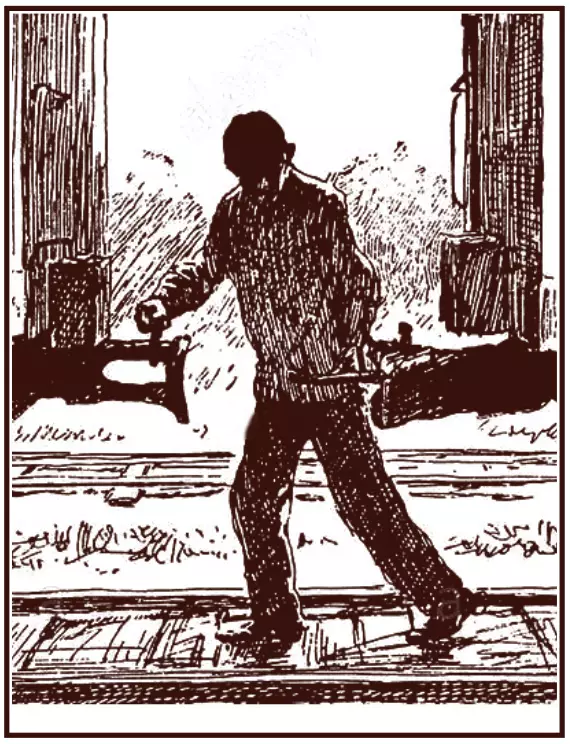

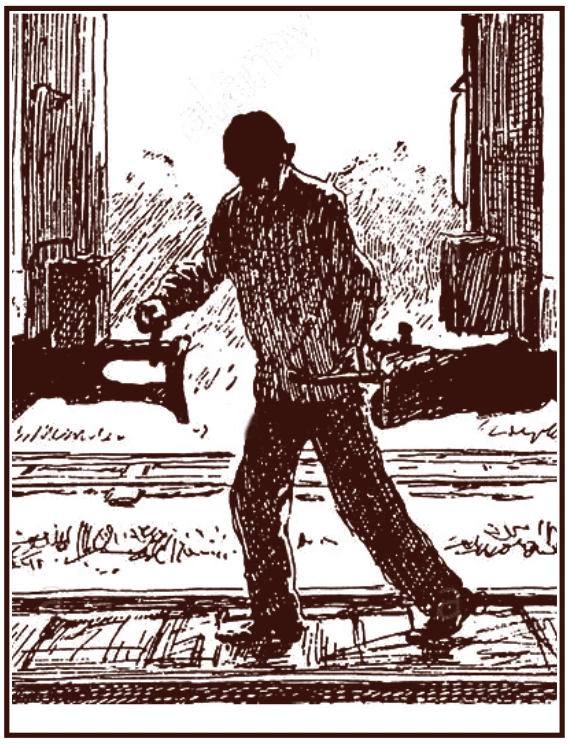

As a brakeman Frank was also responsible for “coupling” cars. This involved standing between cars as one moved towards the other, while lifting a heavy iron link like the one shown below.

Car coupler pin and link, circa 1880

The link was inserted into a pocket on the end of the car. Then the pin was slid through an opening on top of the pocket and through the coupler. This had to be completed successfully to avoid being crushed between the cars. Frank lost three fingers from his right hand when they got caught in a coupler link.

Donated by: J.R. Hoffman

727.35, 36

While coupling cars in Chenoa in 1892, Frank was involved in an accident.

Standing between the engine and a car in the middle of the tracks, Frank signaled the engineer to back up in order to connect a car to the engine. He intended to step on the brake beam (a typical but reckless practice) as he made the connection, but apparently slipped and fell. According to the Bloomington Pantagraph, he was crushed and killed in a scene “too awful and dreadful for description.”

Frank died immediately, leaving behind a wife and two young children. Fortunately Frank was a member of the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen and his family received a $1,000 payment (equal to $29,000 in 2021).

What could railroad workers do to avoid the number of accidents caused by the use of coupler links?

Because of the BRT union and workers’ efforts to improve safety, link and pin couplers were outlawed and replaced with safety couplers in 1893. Safety couplers allowed cars to be joined without a worker standing between the cars.

Unfortunately this change came too late for the Ridge family.

Irish immigrant William Cotter (Unknown-1898) arrived in Bloomington in 1858 and became a track crew foreman on a section gang. He was responsible for a crew of laborers who maintained a length of track. Together they pulled spikes, set new ties, and replaced and aligned rails, before pounding the spikes back in to secure the rails.

In 1859 the railroad was late to pay William and his coworkers.

What do you think they did?

In the mid-1860s William was appointed section foreman for the Towanda stretch of C&A track and managed the Towanda Depot. William and his wife lived in a section house next to the depot where they raised their four sons and two daughters. All of their children learned telegraphy and other aspects of the railroad as they became old enough. His sons, William Jr., John, George, and Stephen, all became high-ranking railroad executives.

William retired after 40 years with the railroad.

Skidding tongs, circa 1890

View this object in Matterport

William and his gang of laborers would have used tongs, like these, to drag the large wooden railroad ties that supported the tracks.

2011.071.2

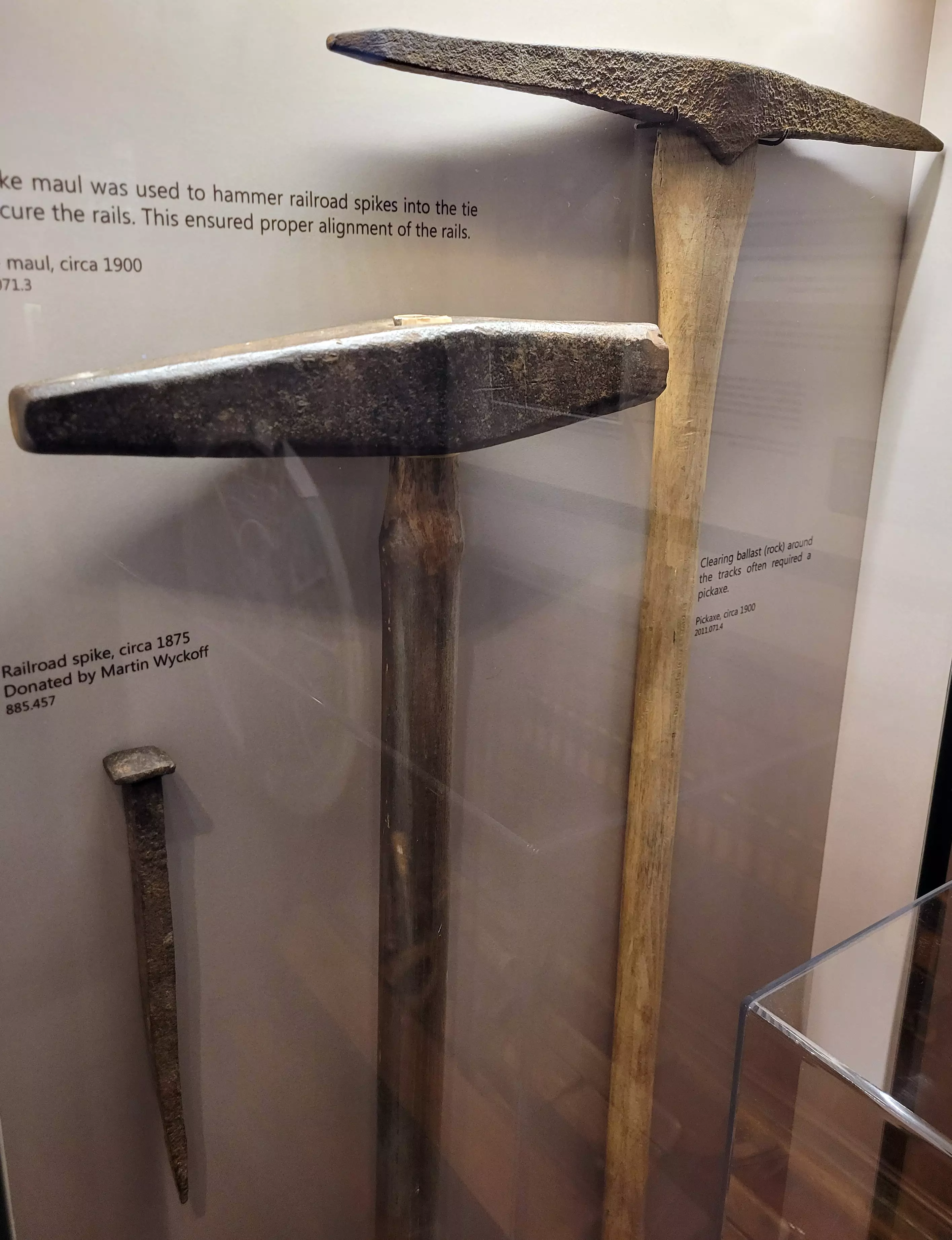

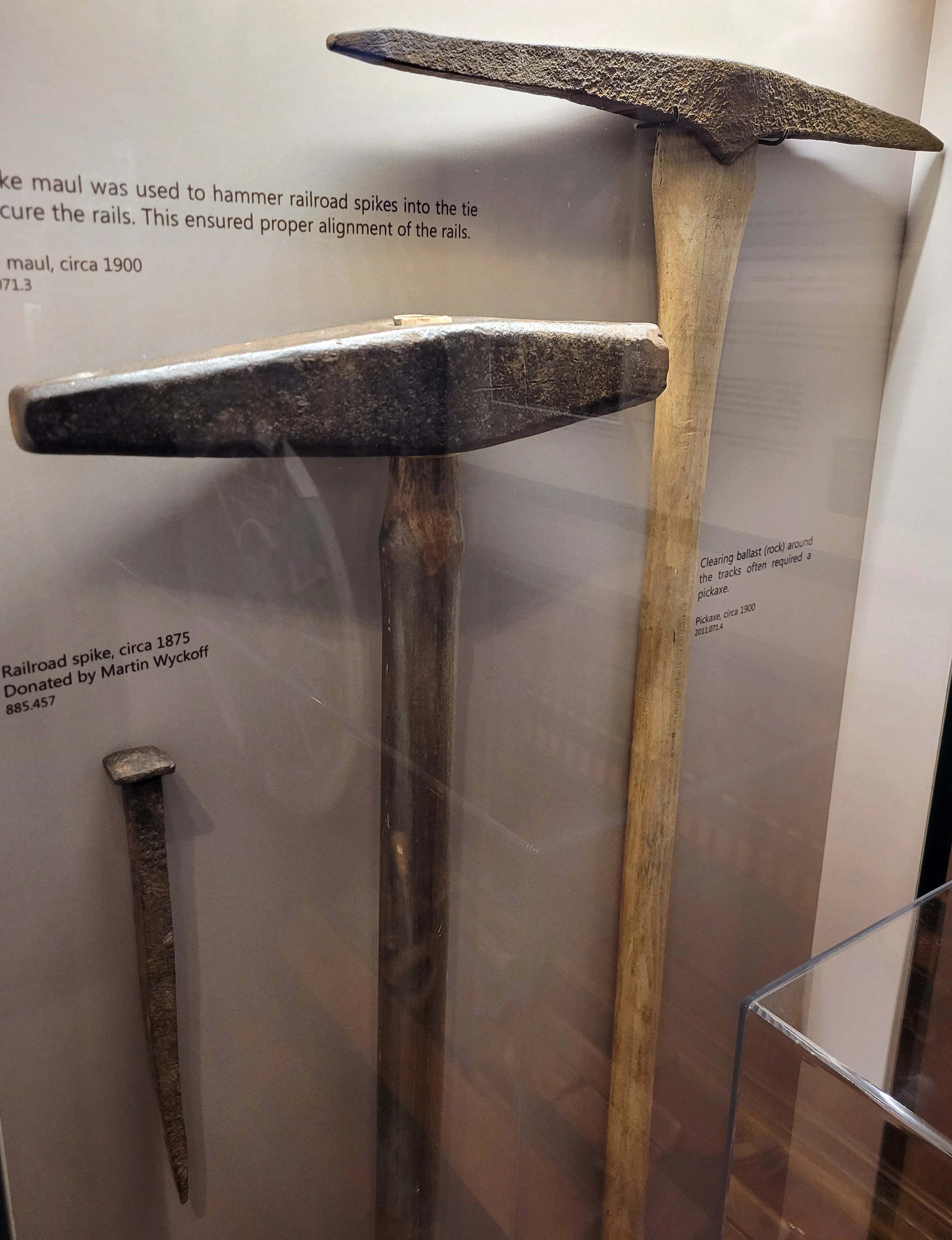

Railroad Spike, Spike Maul, Pickaxe, circa 1875

View this object in Matterport

A spike maul was used to hammer railroad spikes into the tie to secure the rails. This ensured proper alignment of the rails.

Clearing ballast (rock) around the tracks often required a pickaxe.

885.457 (railroad spike), 2011.071.3 (spike maul), 2011.071.4 (pickaxe)

Workers with various skills worked in the Chicago & Alton Railroad shops — Bloomington’s largest employer until the 1930s.

Leonard Seibert (1831-1905) brought needed woodworking and cabinetry skills to the Chicago & Alton Railroad (C&A RR) shops shortly after emigrating from Essen, Germany. His skills were recognized by Chicagoan George M. Pullman, who came to Bloomington’s C&A RR shops in 1858 with a scheme to build a sleeping car that would better serve overnight train travelers.

With the help of C&A RR shop upholsterers, painters, and additional carpenters, Leonard handsomely refurbished two coach cars into the first Pullman sleeping cars, earning himself high praise.

The success of the Pullman sleeping car made Pullman a millionaire.

How do you think Leonard’s life was affected by Pullman’s success?

Leonard’s work to turn Pullman’s vision into a success had little affect on his life, except that he became foreman of the carpenter shop. After his retirement from the railroad, he and his son Leonard Jr. operated a furniture and upholstery shop. A few years later, Leonard returned to the shops where he continued to work until his death.

Leonard Seibert tool chest, circa 1872

View this object in Matterport

Leonard hand-crafted this chest to hold his carpentry and wood working tools. This included the beautiful inlay of a railroad passenger car on the inside of the lid.

Donated by: Leonard Seibert, Jr.

858.604

Pullman sleeping cars were designed to accommodate travelers with distant destinations. The cars featured carpet, drapes, upholstered chairs, and card tables. Hinged seats transformed into lower berths (beds), while iron upper berths were attached to the ceiling by ropes and pulleys. Curtains provided some privacy, and small toilet rooms were located on either end of the car.

The success of Pullman’s first sleeping cars was followed by the production of additional cars in Chicago.

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County