A Cosmopolitan Place – O'Neil Family

Mary Motherway O’Neil lost her husband from fever at the height of the Irish famine. Because she was a woman, she was not allowed to renew the lease on the family farm. She chose to leave—hoping to find a better life for her family.

Colonized by the English, the Irish owned little land and subsisted largely on the potato. A blight devastated this crop in the 1840s and 50s. As a result, nearly 1.5 million people died from starvation or famine related disease. About one million Irish famine survivors immigrated to the U.S.

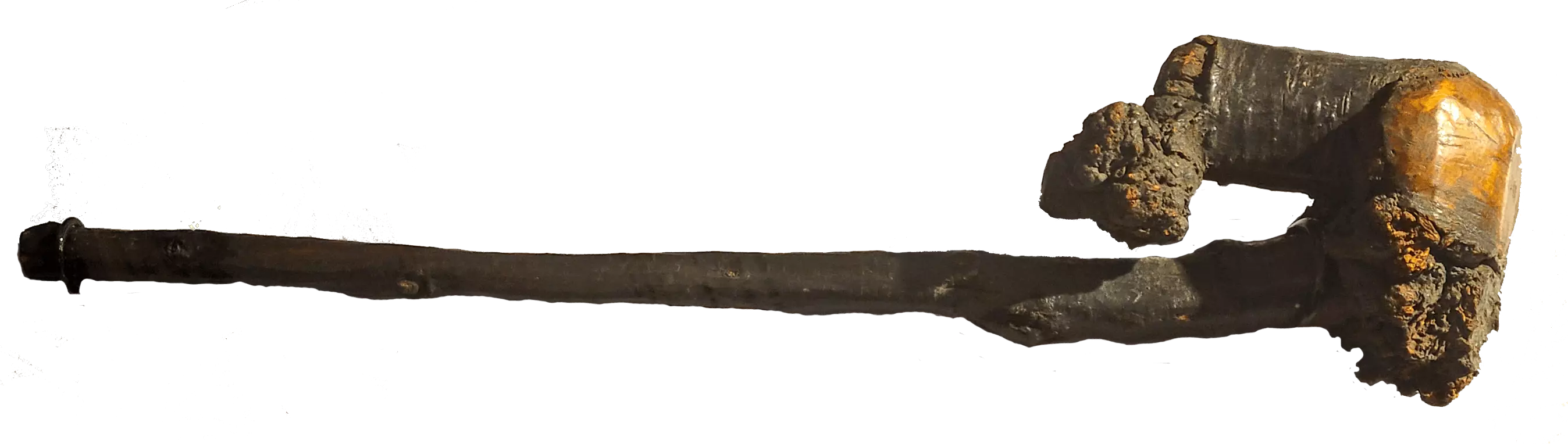

Shillelagh, circa 1865

Besides the dangers of being at sea, ship passengers ran the risk of being robbed. Hanora Foley brought along this blackthorn club, also known as a shillelagh, when she came from Ireland to McLean County. It was used for fending off attackers.

Donated by: Emily Carlton

817.1059

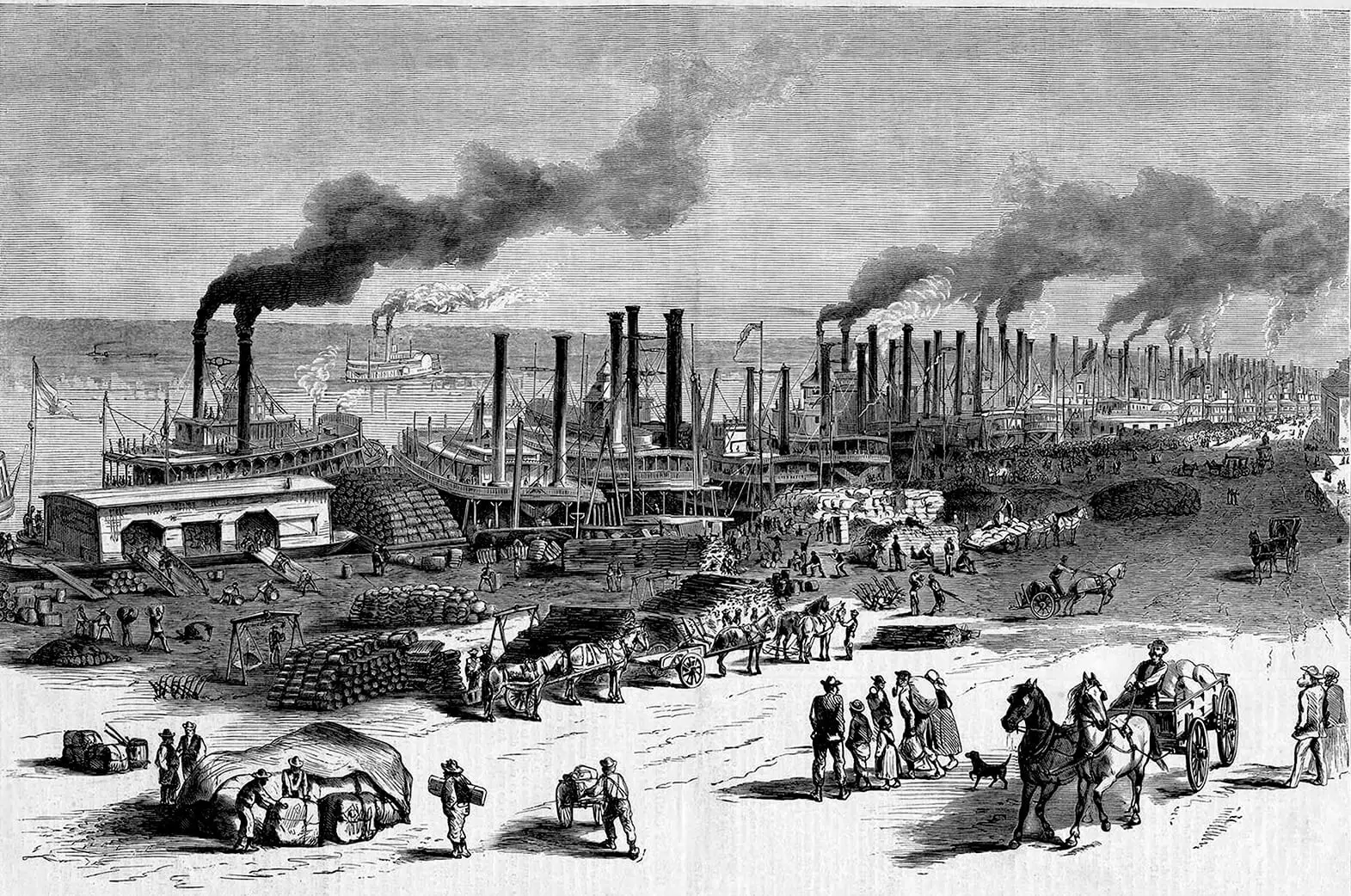

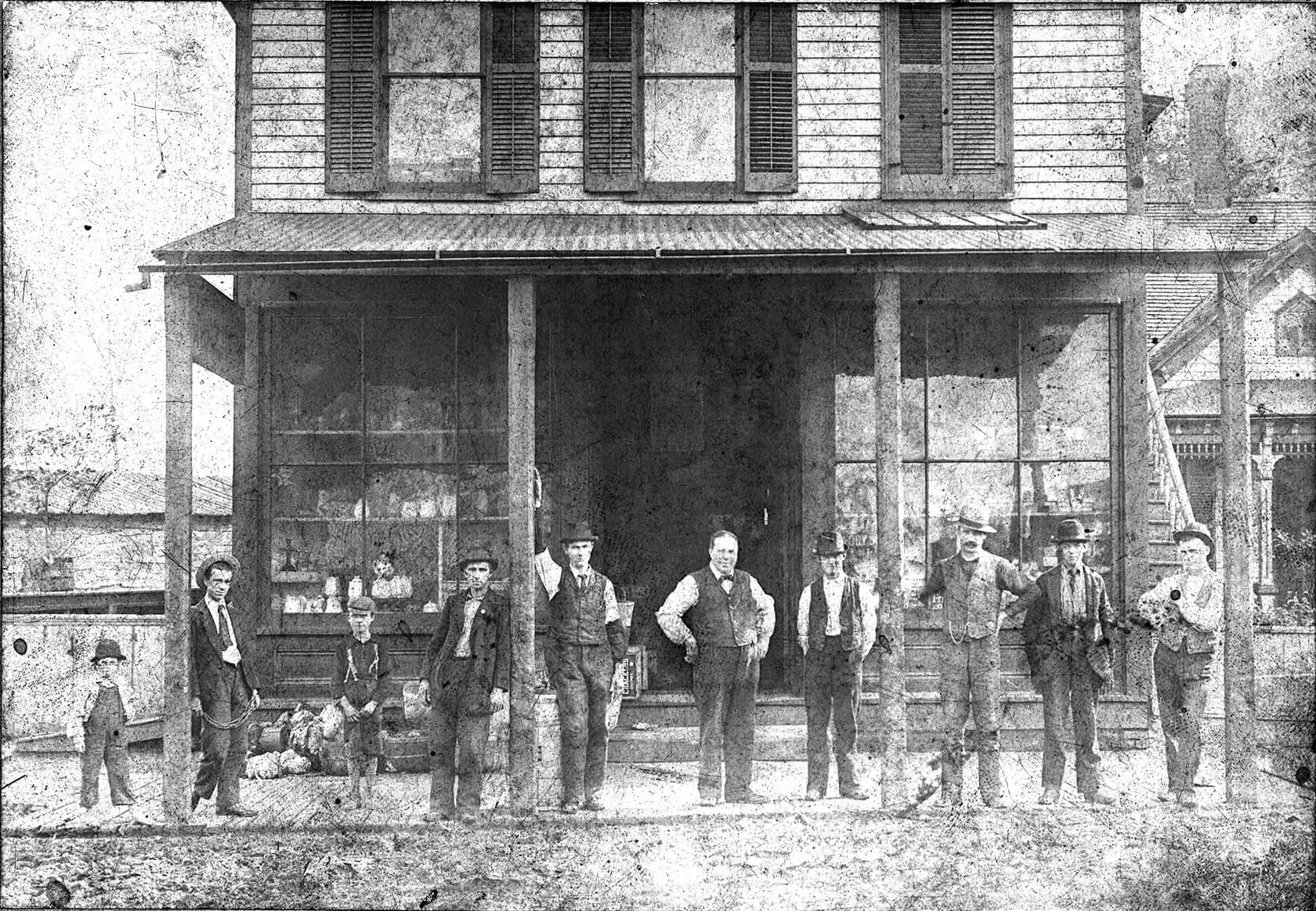

When the O’Neils arrived at the Port of New Orleans, their plans began to fall apart.

Because yellow fever was sweeping through the city, the O’Neils were transferred to a riverboat. This boat took them north to St. Louis. Somewhere along the way, Mary learned that the land company was a fraud and they that had lost all their money.

The O’Neils looked for work in St. Louis.

Phillip, the oldest son, found work on the railroad that was being built from Alton to Chicago. Through this work he learned of opportunities in Bloomington.

They narrowly missed death when the paddle wheel steamer they booked to Pekin in 1853 exploded a few miles up the river.

The explosion killed almost everyone on board, but the O’Neils had missed the boat. Phillip, who was off drinking, could not be found.

They took a later boat and, after arriving in Pekin, traveled overland to Bloomington.

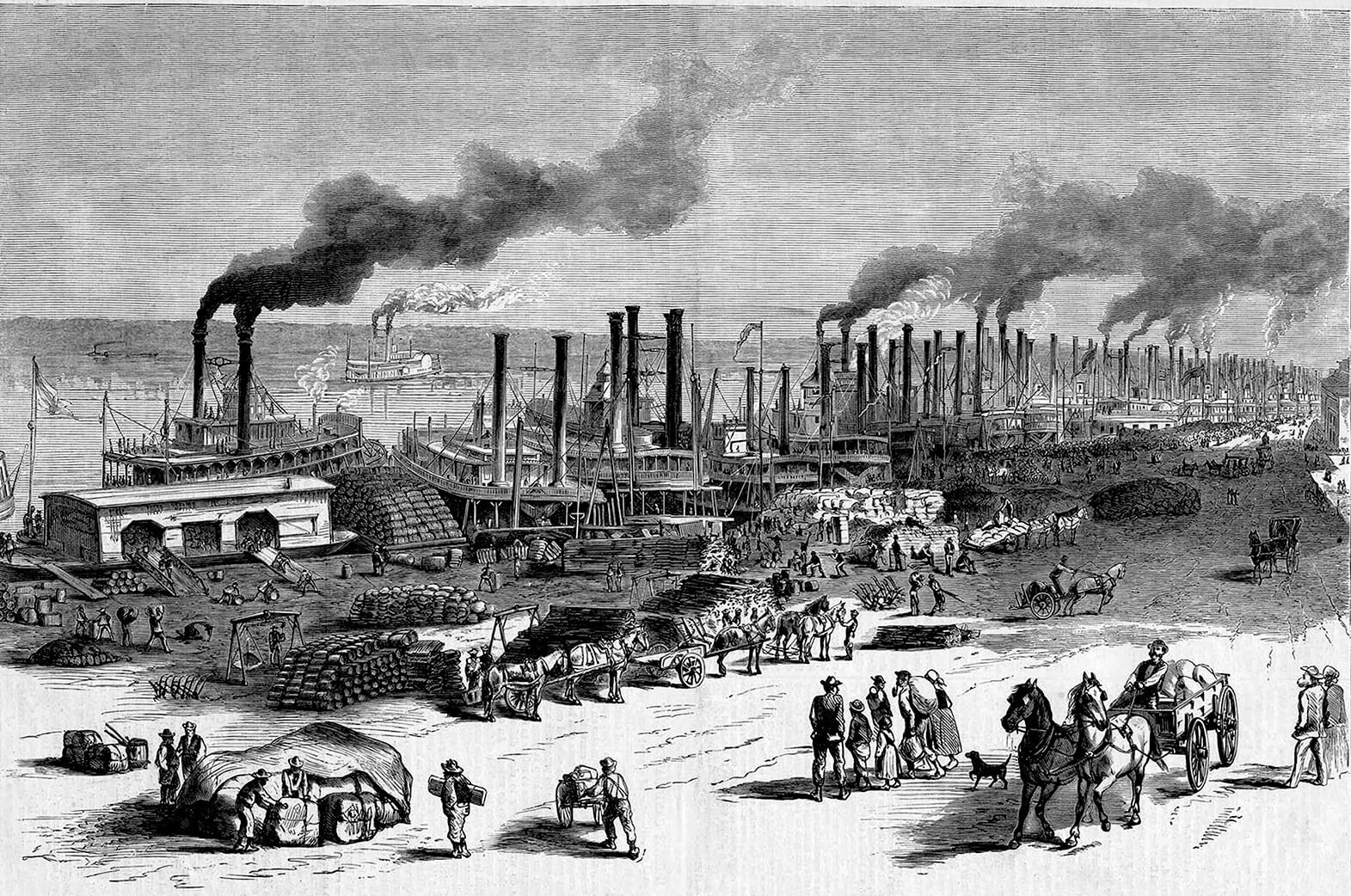

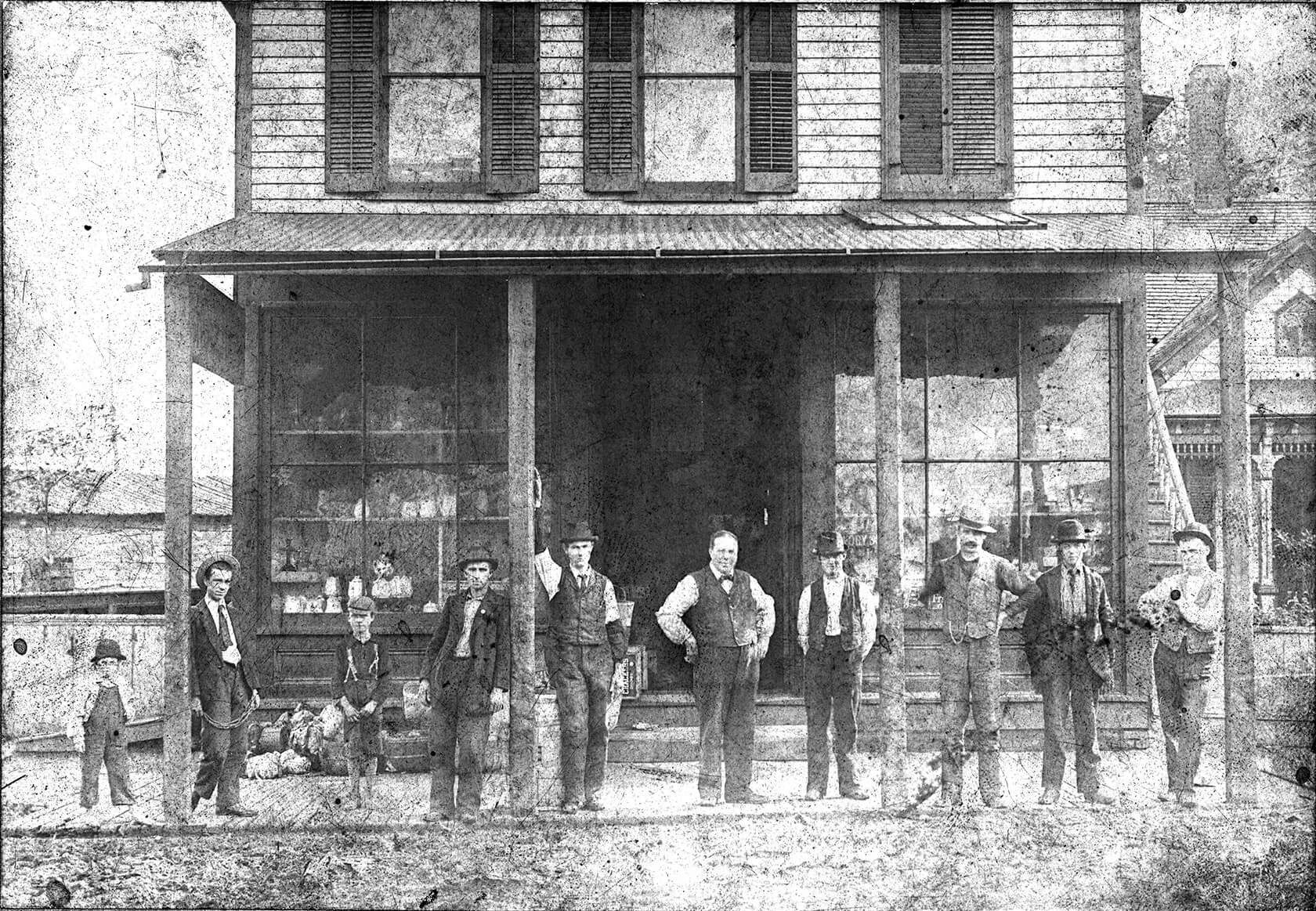

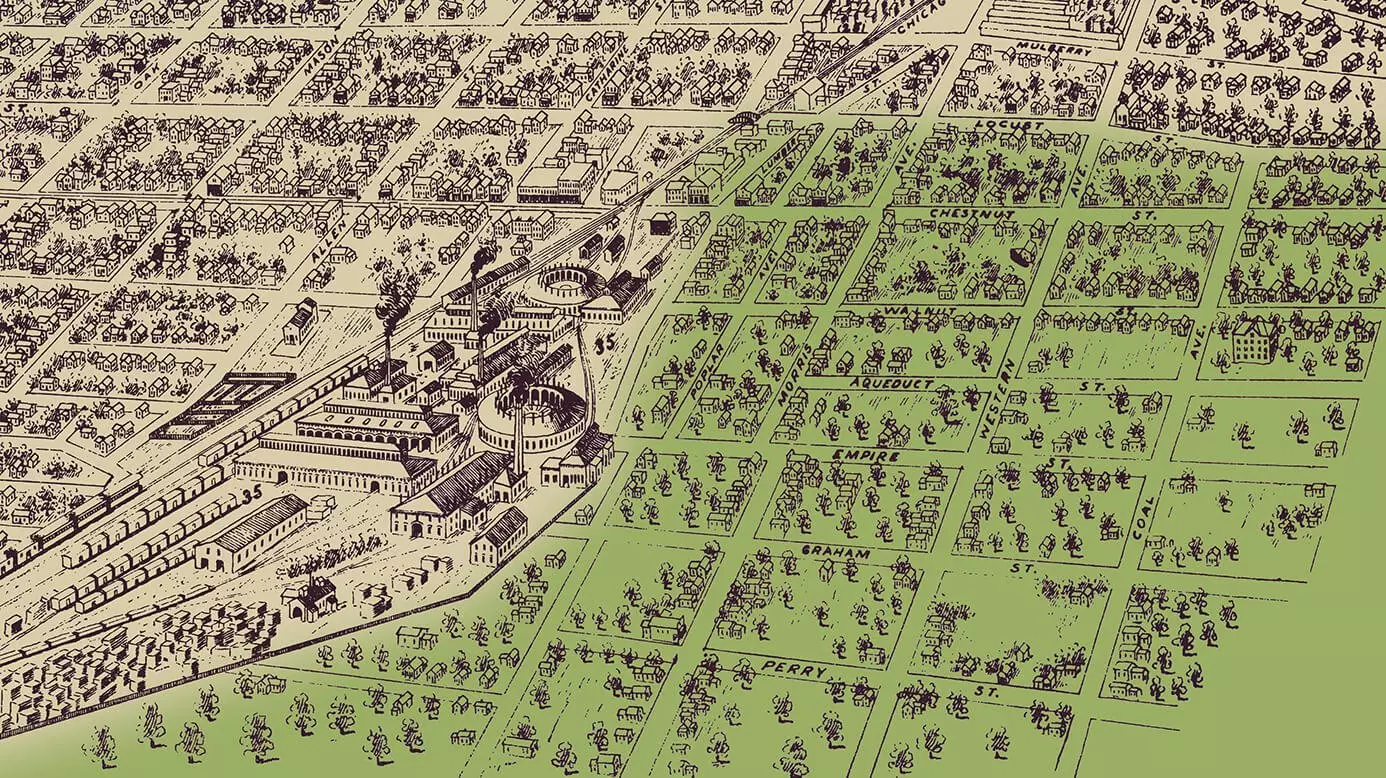

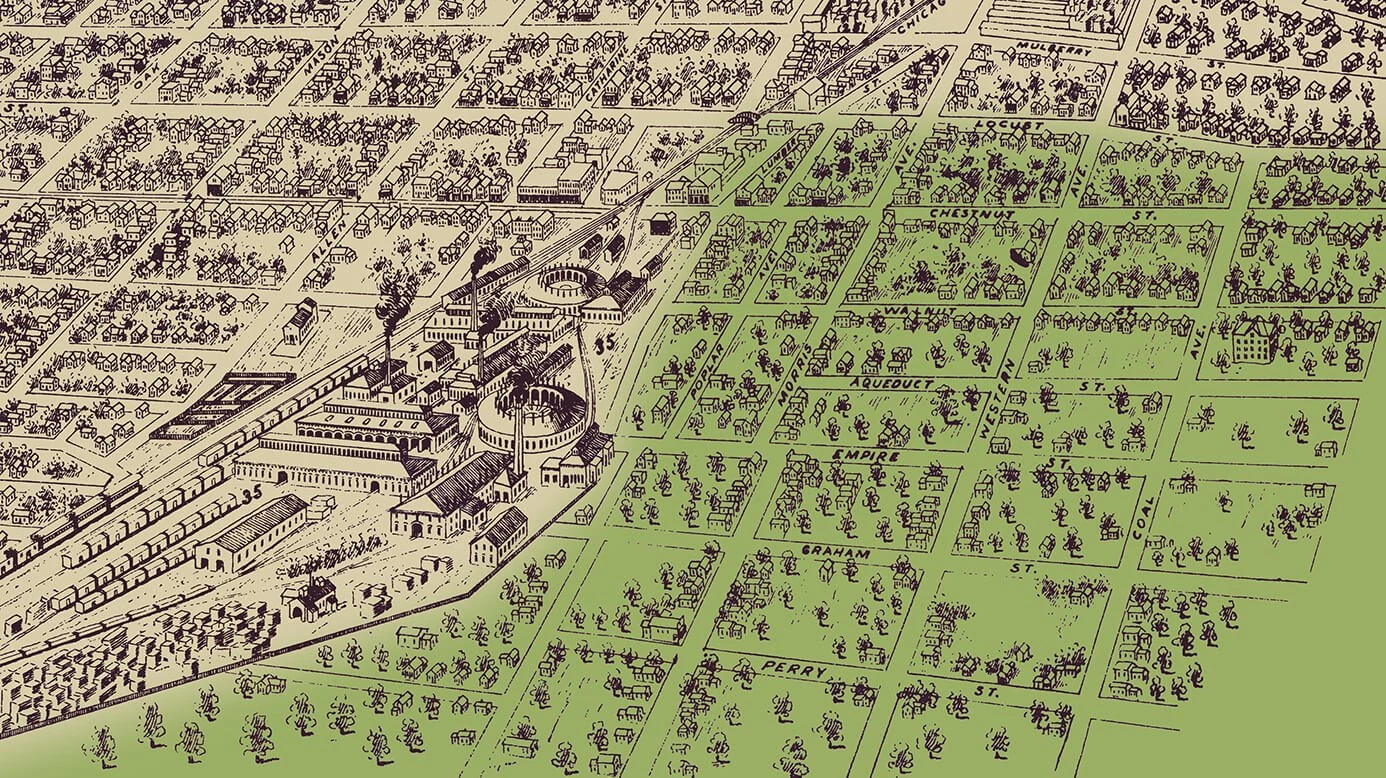

The O’Neils began their new life in Forty Acres. Adjacent to the Chicago & Alton Railroad shops, developers laid out town lots and Irish families borrowed money to build homes. Daniel and William O’Neil opened a grocery store.

Forty Acres, an Irish neighborhood west of the Chicago & Alton Railroad shops, was the center of Irish life. It began as an unincorporated part of Bloomington just outside the city limits. It was remembered as . . .

“[a] squatter town [with] shanties here and there... about each home a garden and a pig sty on the back lot... cow paths across the western prairie led into the brush.”

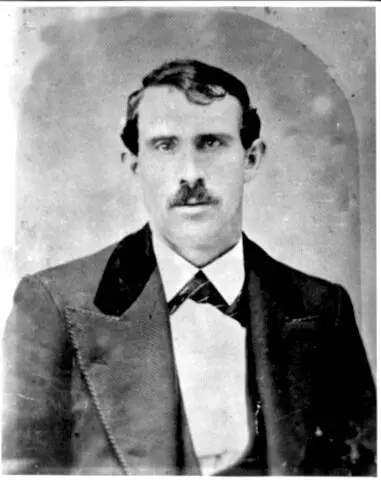

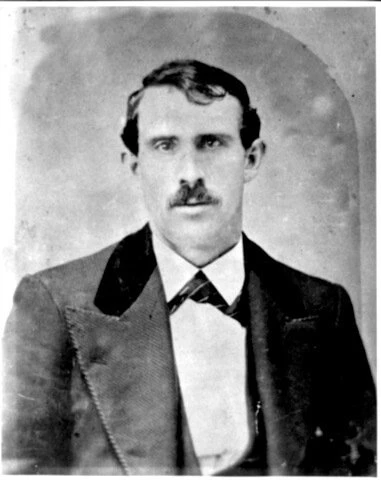

Whether Judge David Davis was a shrewd businessman or was simply impressed by the labors of William O’Neil is unknown. But in 1855 Davis loaned him $100 to build a house for his mother, brothers, and sisters. The home was located on Lumber Street, just behind the O’Neil Grocery.

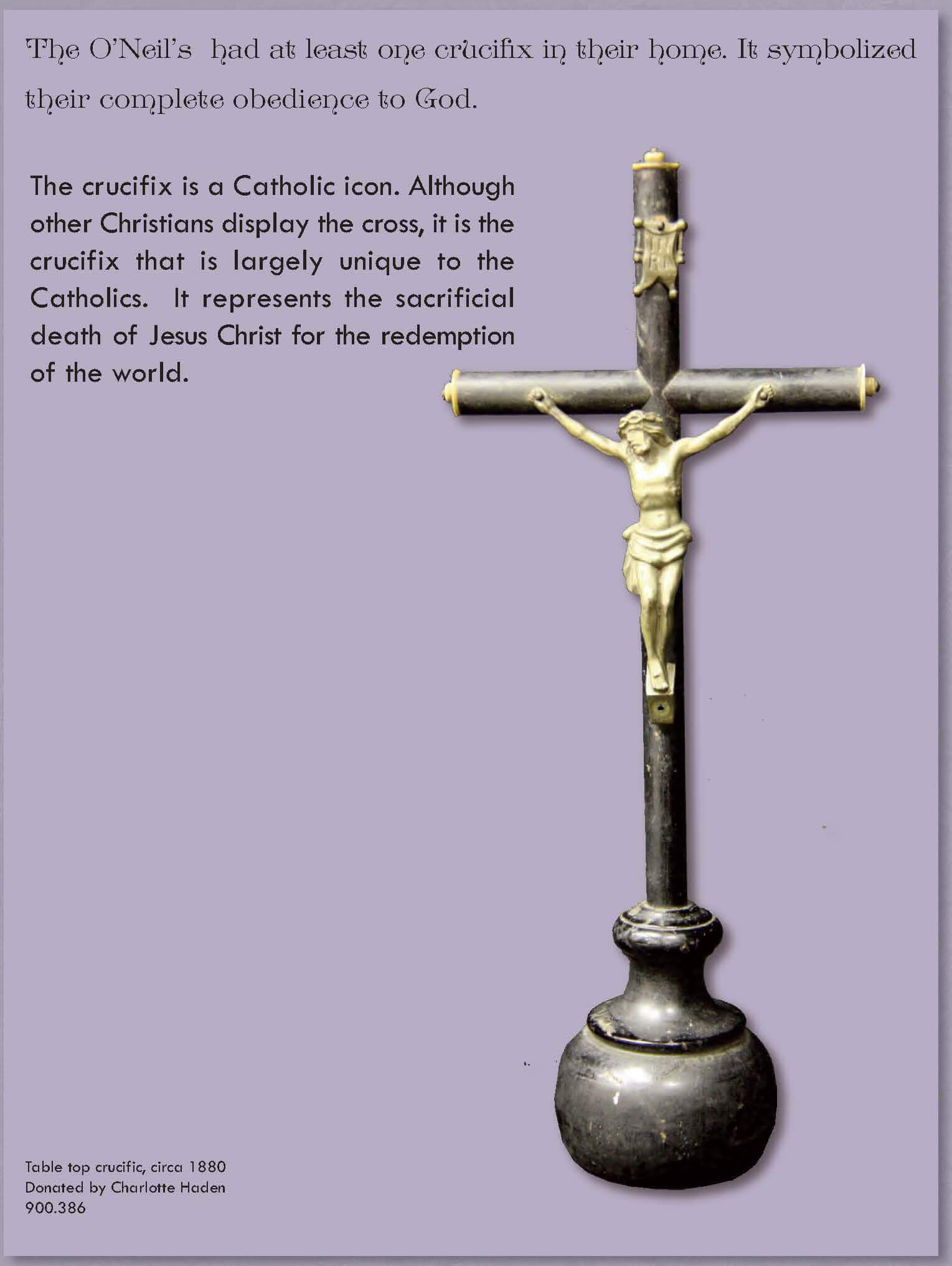

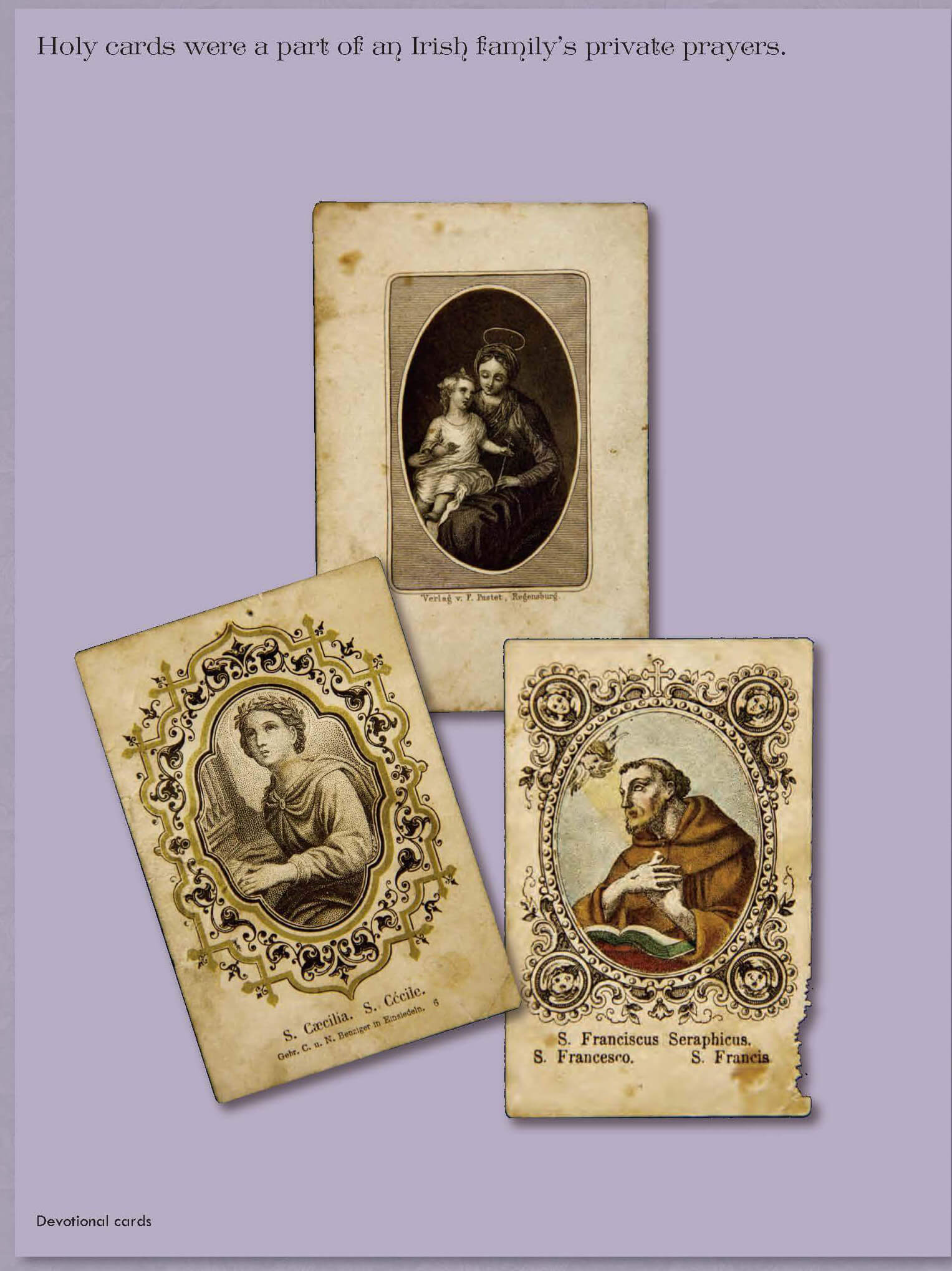

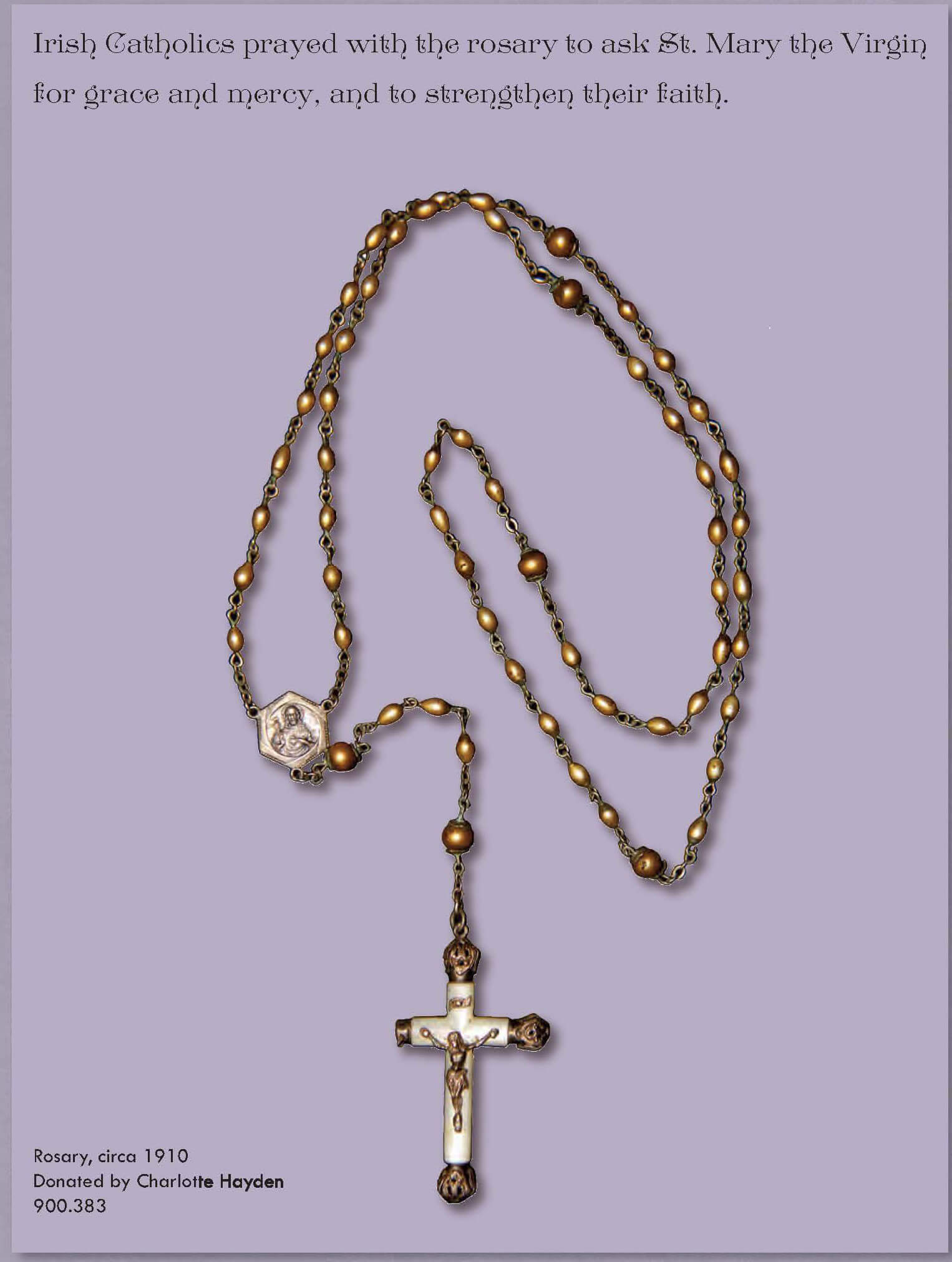

The O’Neils were devoted Catholics who had a lot to pray about. Two of Mary’s sons died violent deaths.

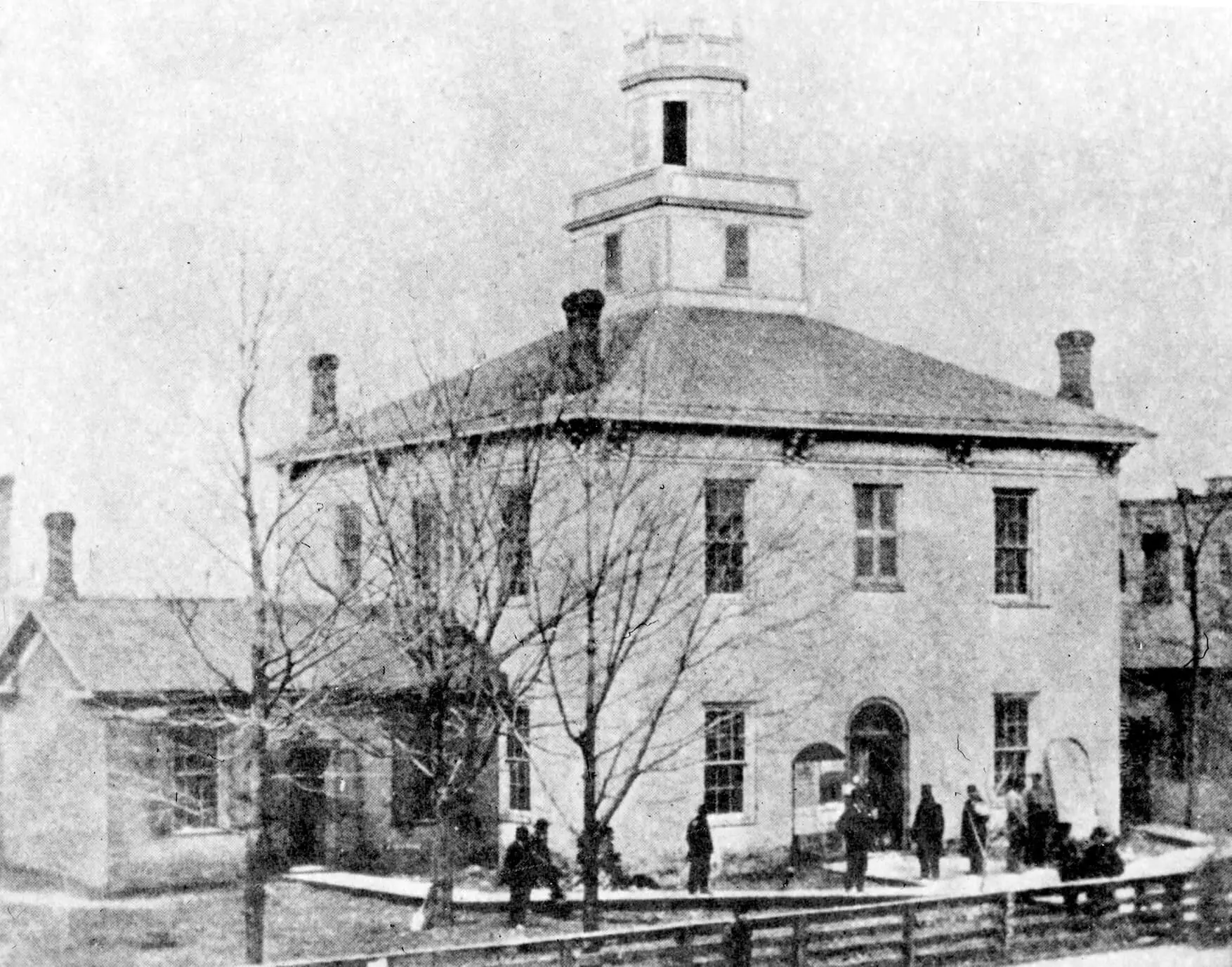

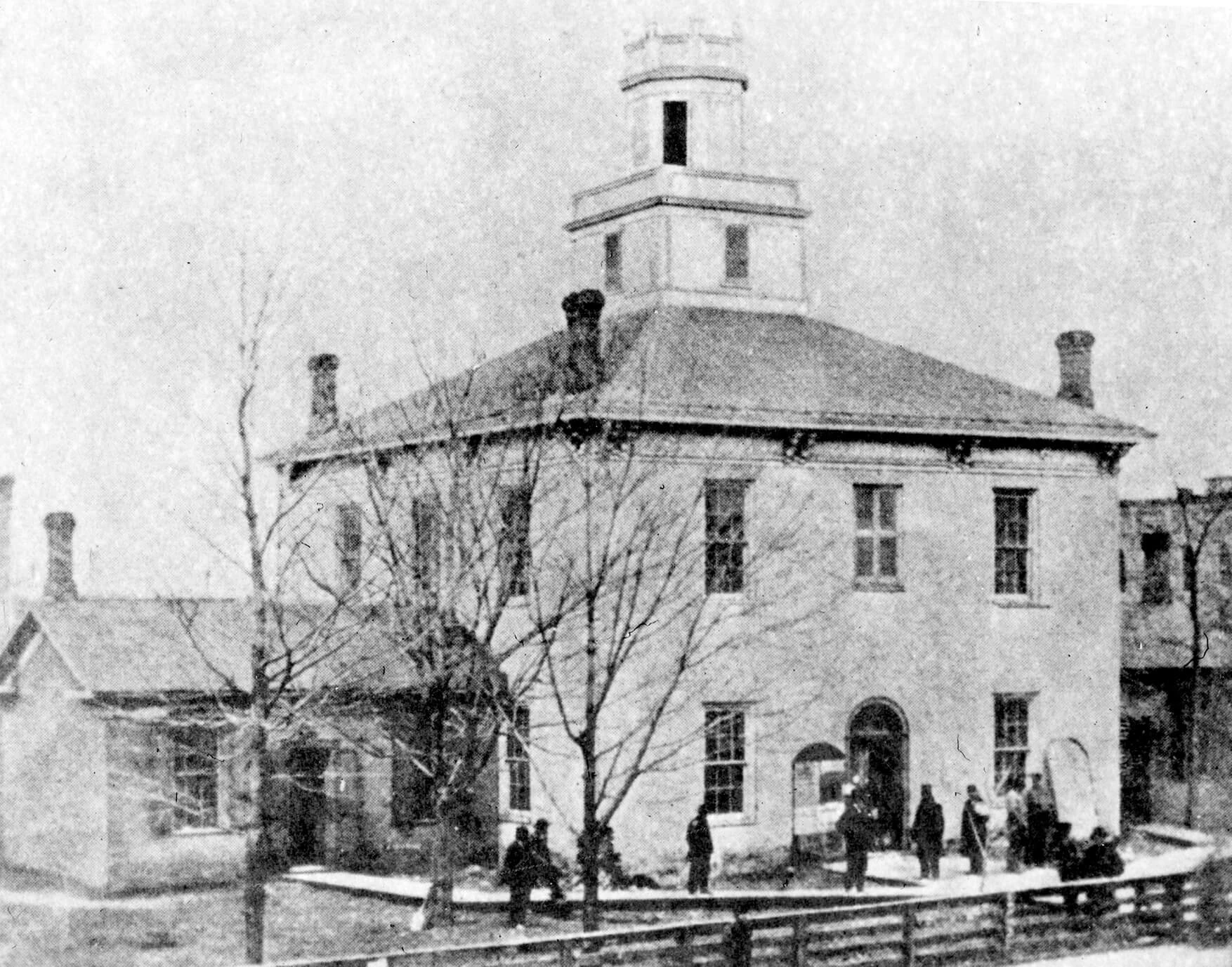

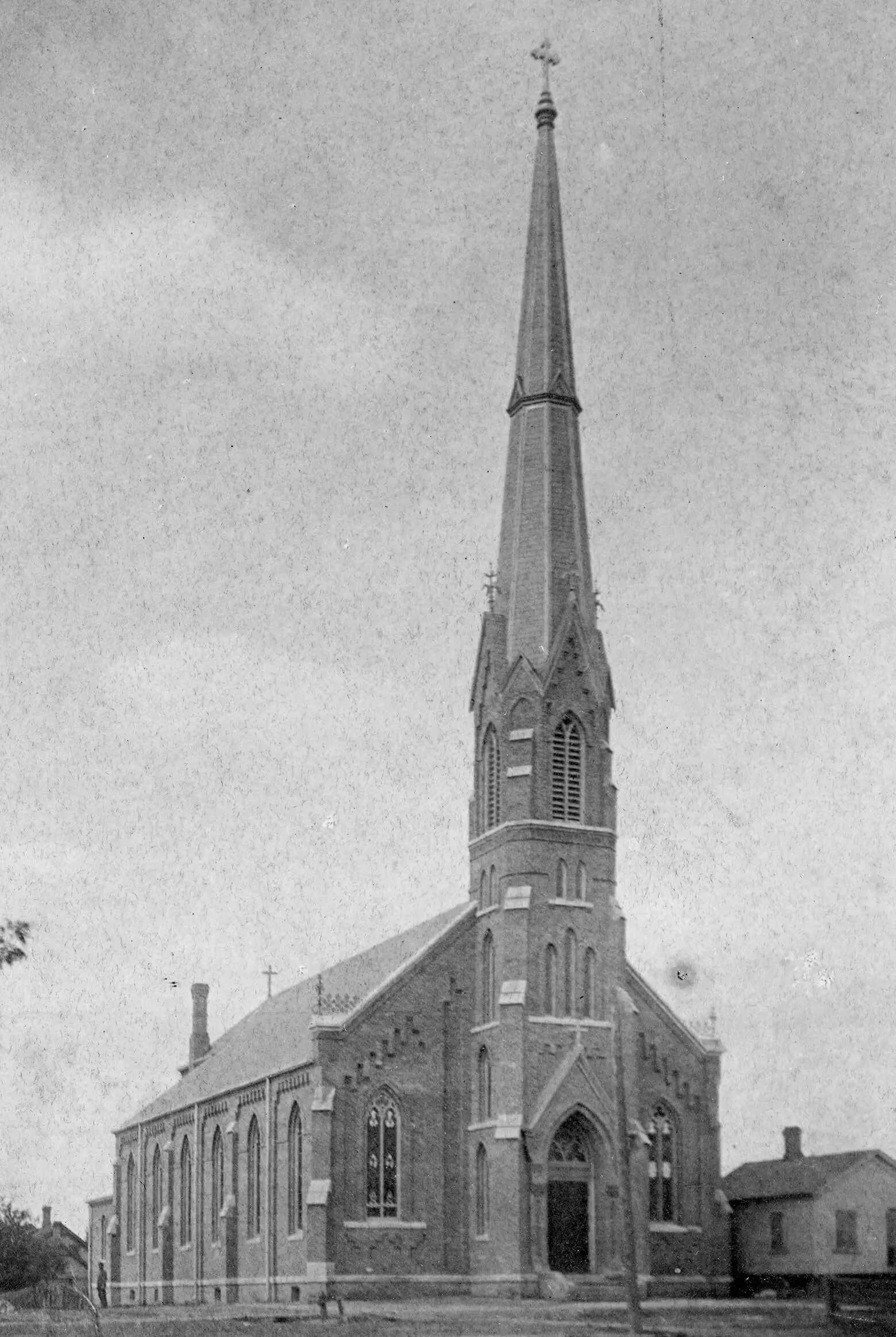

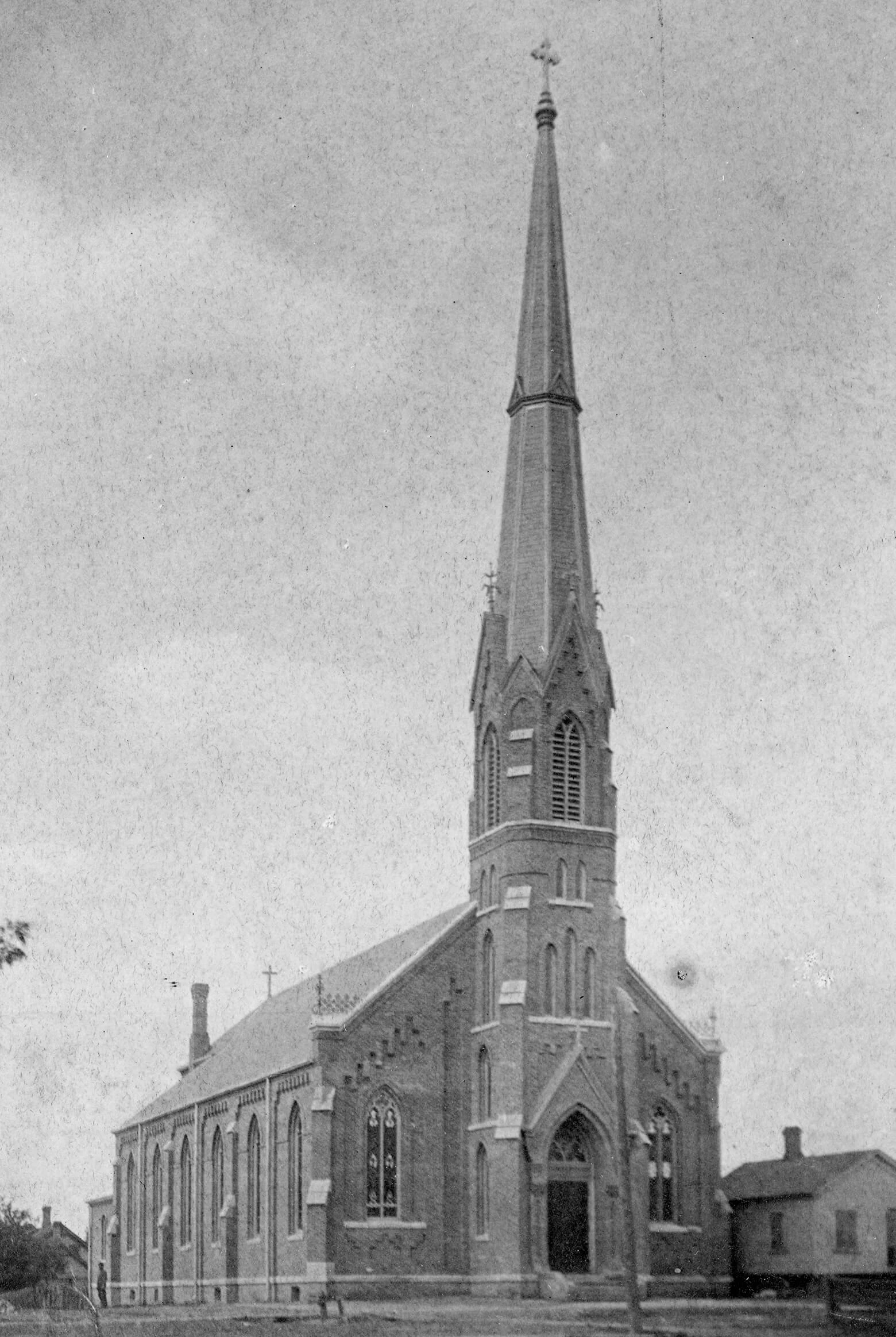

Determined to have their own church, Bloomington’s Catholics purchased the old Methodist church on West Olive Street.

Bloomington’s first Catholic church, the Immaculate Conception, was completed in 1870. Soon after that it was destroyed by a tornado. A Gothic style church (pictured above prior to the completion of its dome) replaced it at the corner of Main and Chestnut Streets. This new church, Holy Trinity, was destroyed by fire in 1932 and replaced by the Art Deco style church still being used today.

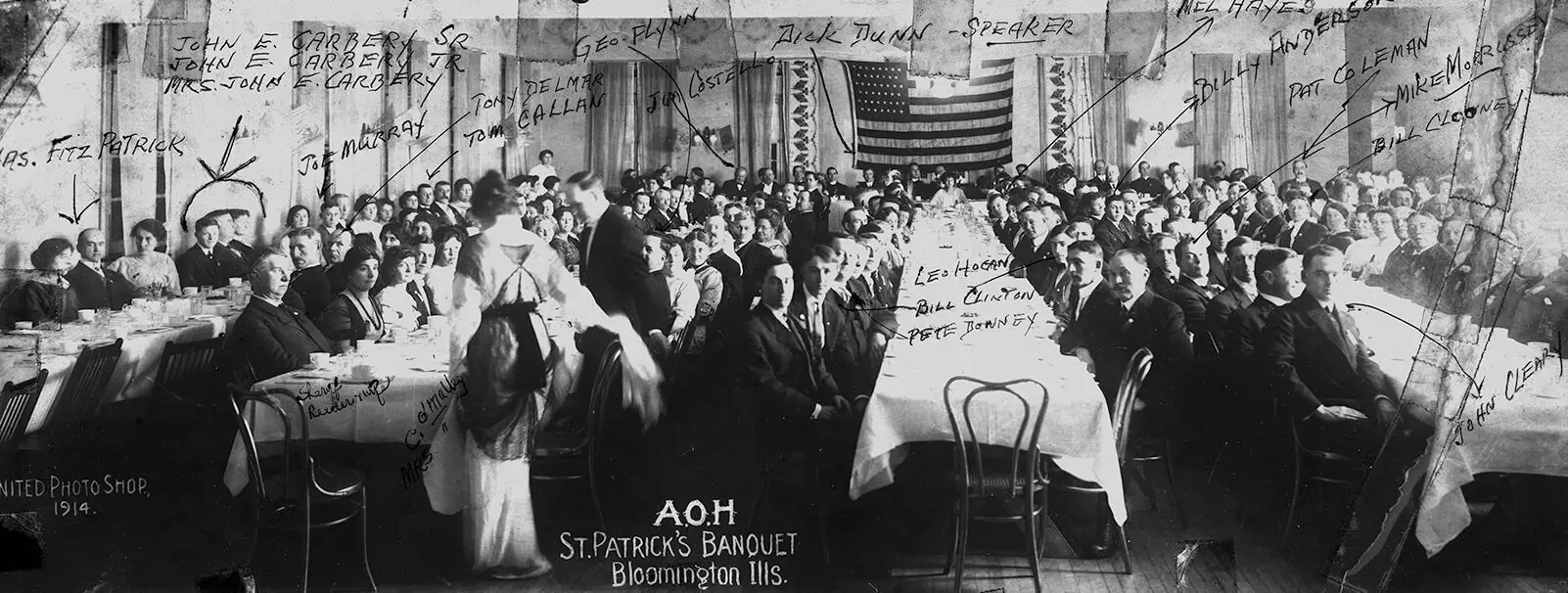

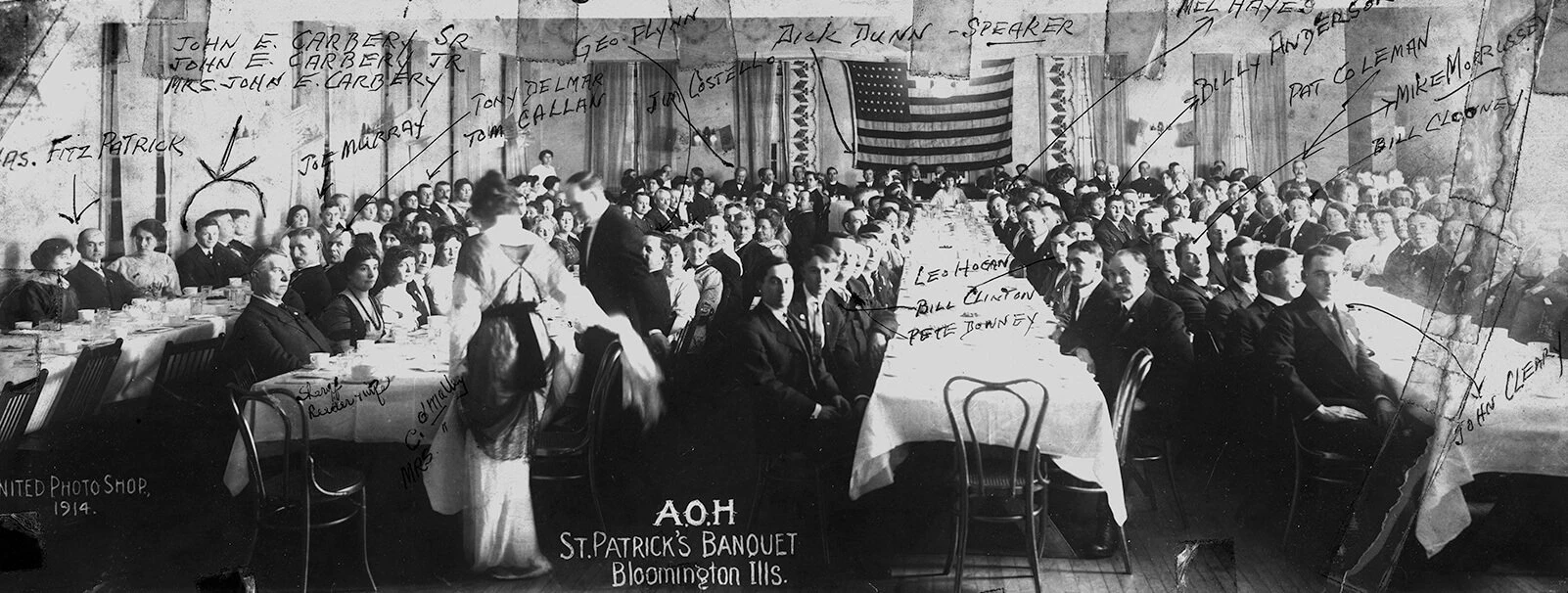

The Irish enjoyed and preferred socializing with each other.

Large numbers of Bloomington’s Irish joined the Ancient Order of Hibernians. This Irish Catholic organization assisted and protected the Church and its parishioners from discrimination. It later evolved into a social insurance and fraternal organization.

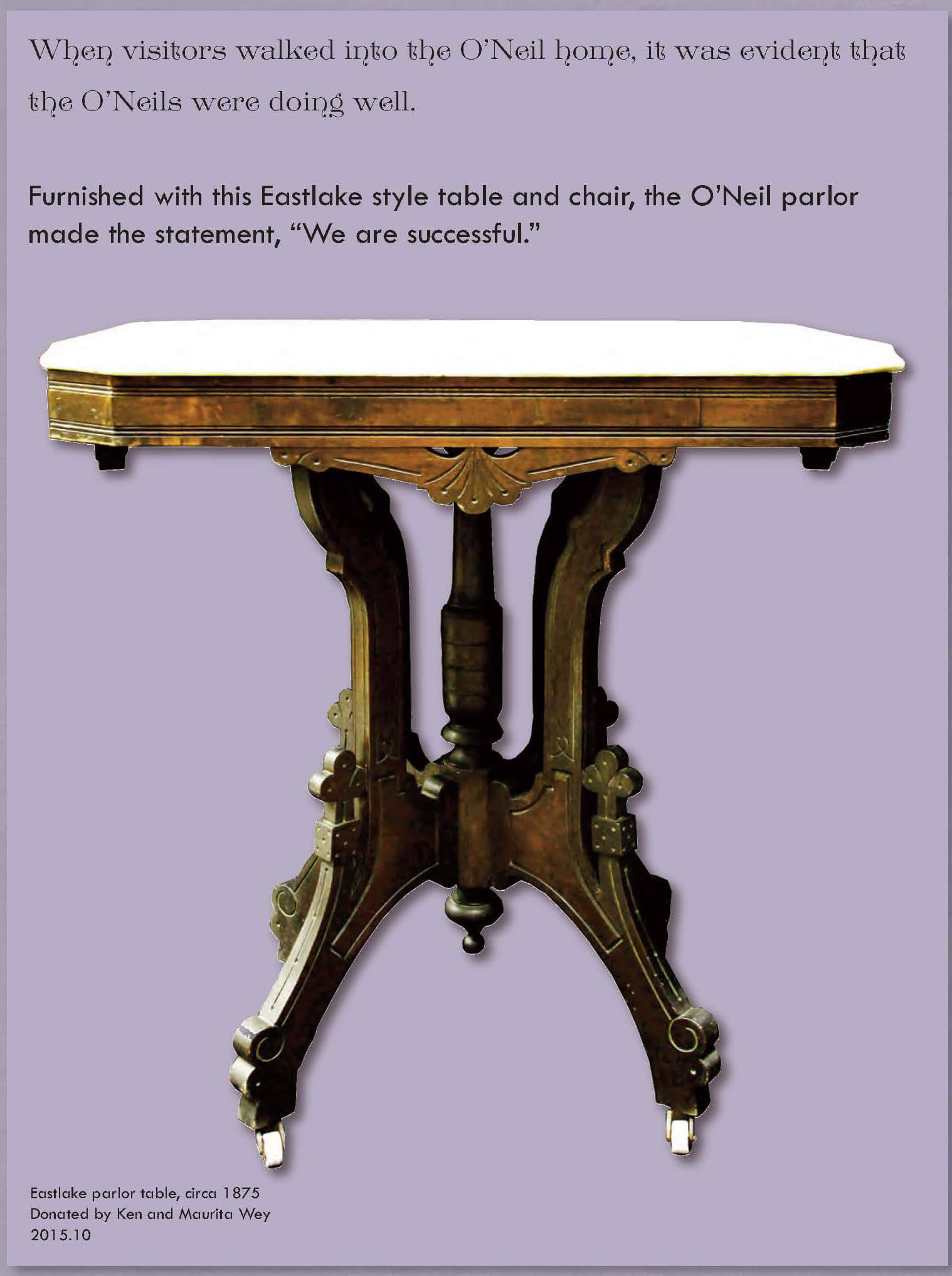

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County