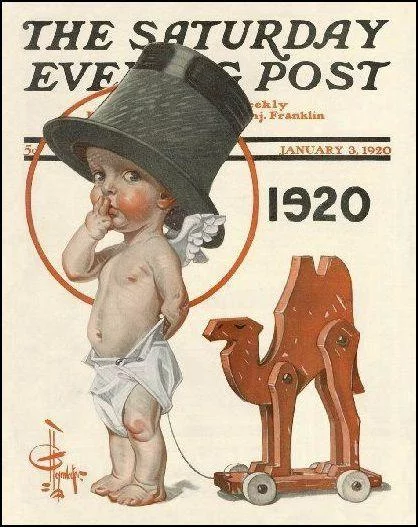

One hundred years ago, New Year’s Eve 1919 brought hope for better days to come. After all, the nation had been deeply scarred by the twin horrors of World War I and the influenza pandemic.

The “Great War” of 1914-1918 claimed more than 20 million lives, and as it neared its grimy, bloody end, the “Spanish flu” (1918-1920) then spread to nearly every corner of the globe, claiming in the process another 50 million or more souls.

Although the Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1918, ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers, it did not take effect until Jan. 10, 1920. In the interregnum, tens of thousands of American “doughboys” (as Uncle Sam’s soldiers were known) remained garrisoned in France and Germany to help maintain the peace and civil order.

A week before the New Year, local residents got word that Julia Scott Vrooman had finally returned stateside after spending something like two years both entertaining U.S. troops in traumatized Europe and lending assistance to benumbed French civilians (she was born and raised at 701 E. Taylor St. in Bloomington, which is now the Vrooman Mansion bed and breakfast.)

Vrooman became something of celebrity as she traveled across France and Germany with her self-styled jazz band. “Where the boys did not have musical instruments they made them out of frying pans and other camp utensils,” she said upon her return to Washington, D.C., where her husband Carl served as an assistant secretary in the U.S. Department of Agriculture. “It is surprising what a lot of music you can get out of string, stretched over a frying pan—if you adjust your ear to the music.”

Also looming over the 1919-1920 holiday season was the Eighteenth Amendment and the ban on the importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages. Prohibition formally began on Jan. 17, 1920 when the Volstead Act—the federal ban’s enabling legislation—became the law of the land.

The federal act, though, did not necessarily prohibit the consumption of alcohol, so many Americans stockpiled cases of beer, wine and hard liquor for the lean years to come. Although the local record is suspiciously quiet regarding well-lubricated area residents, there is no question that New Year’s Eve 1919 was a bittersweet “last call” for more than a few folks!

In many ways, Central Illinois residents celebrated the New Year’s back then much like we do today.

The sound era in motion pictures was a decade away, yet even this early in its history, the silver screen captured the nation’s imagination. As such, many area residents and families used the New Year’s holiday to catch a movie at one of the downtown movie houses.

At the Irvin on East Jefferson Street—the city’s premier “popcorn palace”—it was Billie Burke in “Wanted: A Husband,” and the two-reel comedy “Back to Nature.” Meanwhile, the Castle Theatre showed “Piccadilly Jim” with Owen Moore and Zena Keefe; the Majestic had the Irish drama “Kathleen Mavourneen;” and at the Scenic on the 300 block of North Madison Street it was Harold Lockwood in “Shadows of Suspicion.”

There was live stage entertainment on New Year’s Eve as well. At the Chatterton Opera House on East Market Street, theatergoers were promised a “riot of fun, a feast of music and a bewitching bevy of feminine beauty” in the George M. Cohan and Sam H. Harris production of “Going Up.” The musical was best known for its show-stopper “Tickle-Toe.”

Much like today, “watch night” parties were held by young and old, rich and poor alike. The American Legion sponsored a dance at the National Guard armory in the warehouse district south of downtown. The Dornaus Orchestra—featuring one Dornaus after another on everything from viola to saxophone—provided the music.

The Hills Hotel at the corner of Madison and Washington streets offered a six-course dinner, music by the Alador Orchestra and dancing until 1:00 a.m. Revelers paid $2.50 for the evening of entertainment (adjusted for inflation, that $2.50 would be the equivalent of $34 today.)

As New Year’s Eve 1919 fell on a Wednesday—traditionally the prayer meeting night for houses of worship—a number of area churches also held watch parties up to, and beyond, the midnight hour. At Grace Methodist in Bloomington, the Rev. B.F. Shipp delivered a bit of year-end sermonizing before stepping aside so the church’s Epworth League (the Methodist young adult association) could take charge. The congregation then rang in the New Year with a prayer.

The 1919-1920 holiday season also occurred during the First Red Scare, a time when the U.S. Department of Justice under Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer persecuted so-called political and labor radicals. The Palmer Raids, conducted in November 1919 and January 1920, sought to capture, arrest and deport leftist leaders, many of whom were Italian and Eastern European immigrants.

As such, the New Year’s Day edition of The Pantagraph featured a front-page declaration by Attorney General Palmer in which he promised to wage “unflinching, persistent, aggressive warfare” against radicals and likeminded fellow travelers. “We have found,” he declared, “that the ‘red’ movement does not mean an attitude of protest against alleged defects in our present political and economic organization of society … It is not a movement of liberty loving persons, but distinctly a criminal and dishonest scheme.”

The annual New Year’s dinner for the area’s less fortunate children was held at the YMCA building, then located at the southeast corner of East and Washington streets in downtown Bloomington. Grain and lumber merchant John Geltmacher started the tradition back in the mid-1890s. Although he passed away in 1904, he left behind funds to continue the holiday meal, which lasted into the mid-20th century. Geltmacher was also an anti-alcohol zealot, so the dinners were often prepared by the local Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, and the children had to sit through songs, skits and sermons on the evils of drinking.

New Year’s Day 1920 ushered in a new decade. As such, enumerators were preparing to pound the pavement for the U.S. government’s decennial census—just like today! The nation’s 14th census began Jan. 5, 1920, and lasted one month. Those working to count Bloomington residents included Harry A. Slack, Mary Normile, Wilber Dillon Clapp and Ansel F. Stubblefield, among many others.

A snowstorm resembling “one of those howling western blizzards” swept across Central Illinois during the height of New Year’s Eve revelry. “The year 1919 went out in a rage,” noted The Pantagraph. “A strong north wind sent the snow swirling and eddying about and conditions out of doors were anything but pleasant.”

Perhaps not pleasant from the viewpoint of fuddy-duddy adults, certainly, but the snow was surely welcomed by those children with bright-and-shiny sleds under their family’s Christmas tree.