In the late 1800s, there was no better place in Bloomington to grumble about the “gov’ment,” debate the issues of the day, recount a well-worn tale of pioneer pluck, or simply doze away the afternoon, than Adam’s Ark, a cigar store on the Courthouse Square.

“The Ark,” it was said, was a place where “anecdote and repartee poured out like Old Crow from a stone jug at an old-fashioned barn raising.”

It was an all-male mecca for retired politicians, old farmers, bank and shop clerks, Courthouse employees and the usual coterie of loafers and eccentrics with a gift for gab. They and other sorted hangers-on liked to gather around the “tobacco-bespattered stove” to tackle the unsolvable problems of the world.

The cigar shop was known for its informal debates over matters ranging from the weighty to the trivial. “It was there that the great affairs of state were settled,” observed The Pantagraph in 1924, “presidents made and unmade, governors nominated and thrown out of office, congressmen and senators selected and cast aside and all of the county, township and municipal affairs adjusted.”

The Adam in Adam’s Ark was Adam Guthrie. Born in 1825 in Ohio, Guthrie was a wee bitty thing when his family settled in McLean County, first in the Funks Grove area and then north of Towanda. The family eventually moved to Bloomington—that was in either 1831 or 1832 (accounts differ)—and it was here that Guthrie lived out the remainder of his long life.

During the Civil War—this well before his cigar shop-owning days—he enlisted in the 94th Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry, participating in the Battle of Prairie Grove in Arkansas before being discharged due to illness.

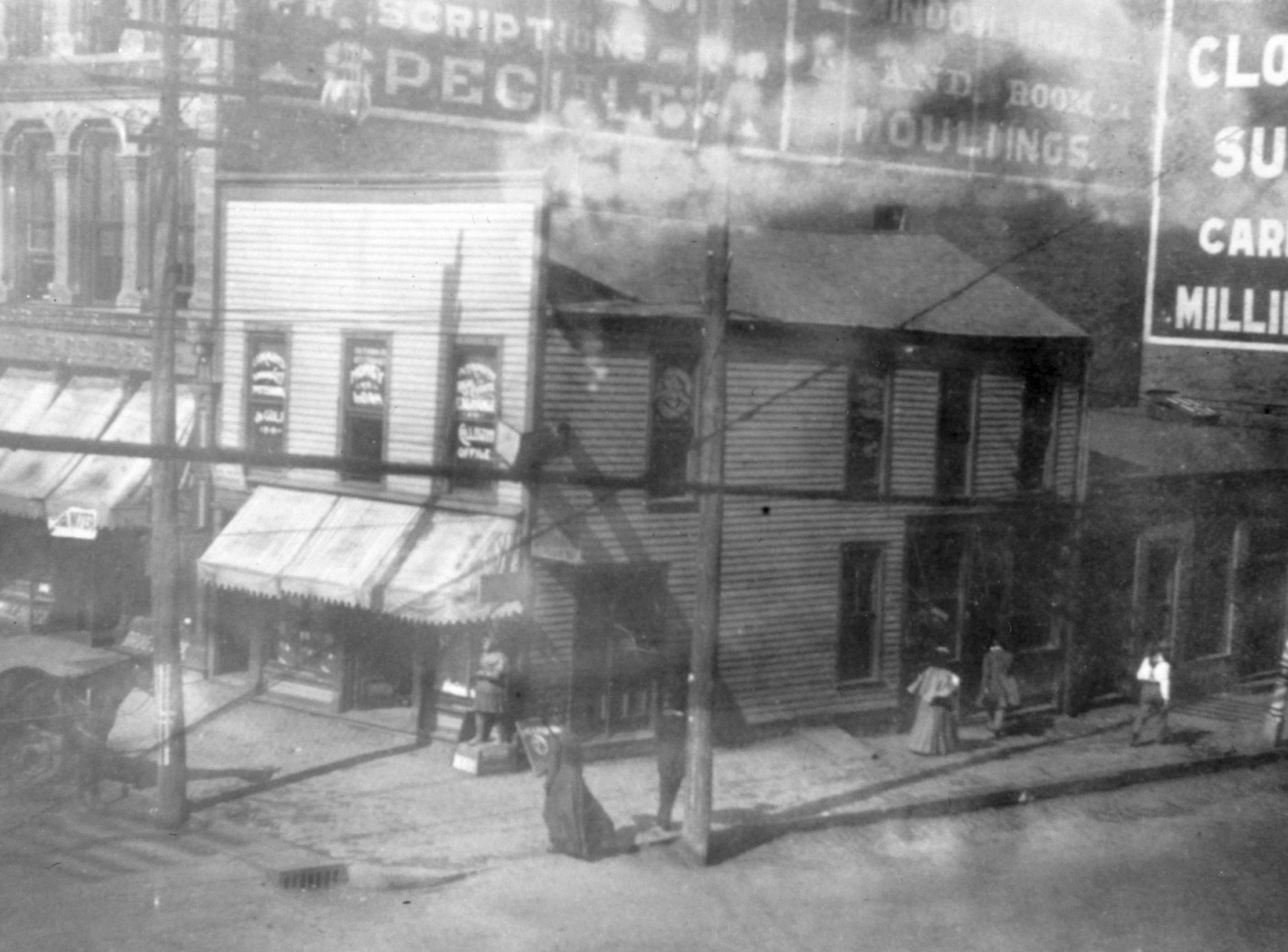

Guthrie first worked as a plasterer before embarking in the retail tobacco trade. Around 1880, he began running a cigar shop out of the storefront of a two-story building on the corner of Main and Jefferson streets (see accompanying photograph.) The ramshackle affair was the last wood-frame building on the Courthouse Square when it was lost in the Great Fire of June 19, 1900.

“Adam Guthrie is the Noah to the Bloomington Ark and devotes his time to umpiring debates and selling cigars, fine cut and navy twist, to the chair-warmers,” remarked The Bulletin, a gone-but-not-forgotten Bloomington daily paper.

“Everybody knew him,” related his grandson, the Rev. Sidney A. Guthrie. “He stood six feet, was slender, and had a full white beard. He wore a black frock coat until he died.”

The Ark became a favorite gathering place for early settlers—“the rendezvous for the pioneers who toast their shins at the stove and tell pipe stories.” Frequent visitors included Bloomington mayor Benjamin F. Funk; John Dawson (the first Euro-American settler born in McLean County); Abram Brokaw (the “Bro” in BroMenn); and “Private” Joseph W. Fifer, a former governor.

“When arguments grew too acrimonious,” read one of many reminiscences of The Ark, “old Adam started scrubbing the floor and made the disputants scatter.”

Told and retold were the pioneer tales of hardihood and foolhardiness, involving the likes of wolves, prairie fires and meteorological calamities, such as the “Deep Snow” of 1830-1831, and the “Sudden Freeze” of 1836.

At The Ark, someone quipped, the Deep Snow “got deeper every year.”

From time to time on slow news days, a Pantagraph scribe would stroll over to Guthrie’s shop in search of a good story to fill a column of newsprint. “Yesterday was a dull day about town and there was a quorum at Adam’s Ark,” noted one such reporter in early January 1894. “Adam dozed peacefully in the corner behind the stove, occasionally waking from his nap long enough to object to some reckless statement of fact.”

That day “Uncle” Ike Lash told a story of two men walking through some timber near Tremont when one aimed and fired a rifle at a sapsucker in a nearby tree. “There was a sort o’ whizzin’ and snappin’ in the timber for a second or two, and blamed if that feller that was standin’ beside the man that fired the gun didn’t fall dead in his tracks, with a rifle ball in the back of his head,” Lash relayed. “That consarned rifle ball had jest glanced from the sugar saplin’ to another, and then to another until it made a clean circle.”

How, exactly, did Uncle Ike know this story to be true? Well, he said, he knew someone who just so happened to be the brother-in-law of someone who just so happened to witness the accident from afar.

After the 1900 fire, Guthrie relocated his business to the Main Street side of the still-standing Evans Building, north of his old location. Even in his later years, Guthrie was known for his steel-trap mind, especially when it came to the past—he was called “an animated encyclopedia of doings in early times.”

Adam Guthrie passed away in September 1904 at the age of 79, and not long after, the Ark closed its doors for good.

In 1894, journalist and diarist Edward Wilson penned an appreciation of Adam’s Ark and its role in the local cultural landscape. In a poem, Wilson writes from the perspective of a local farmer who “don’t care a cent to go visitin’” Bloomington “exceptin,’” that is, Adam’s Ark.

I’m jest a plain sort of a feller

A stumpin’ around on the farm.

… on long rainy days, ‘er in winter,

When the cronies ‘er there, I’ll remark,

That no matter how hard blows the blizzard,

It’s all homelike at Adam’s Ark.